|

|

Sometimes it can feel as though the entire long session of the General Assembly was about the budget. After all, the state hadn’t had one since 2018, Gov. Roy Cooper and legislative Republican leaders were playing nice for the first time in a long time, and the judge in the Leandro case was threatening to force the General Assembly to spend about an additional $1.7 billion on education. But, as the name suggests, the session was long, and a lot has happened since lawmakers gaveled in back in January.

From requiring teachers to post lesson plans online to critical race theory to dealing with COVID-19, here is what happened this long session.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

In-person education

When the General Assembly convened for the long session in Jan. 2021, many schools were still virtual. At the start of the 2020-21 school year, Gov. Cooper told schools they could open under a hybrid in-person and remote learning option or an all-remote option (either plan B or plan C). In Oct. 2020, Cooper allowed elementary schools to open fully in person under plan A, but grades 6-12 remained in either hybrid or fully remote learning.

One of the first things legislators tackled this session was returning students to school. The Senate rolled out legislation that would require schools to provide in-person learning for exceptional needs students under plan A and either fully in-person learning (plan A) or hybrid learning (plan B) for all other students. No school would be able to remain under plan C, or fully remote learning. That bill made it all the way through the General Assembly before being vetoed by Gov. Cooper.

At that time, vaccines were first being rolled out in North Carolina, and teachers were not yet eligible to receive them. They became eligible on Feb. 24, and things moved rapidly from there.

After lawmakers failed to override Cooper’s veto of their in-person learning bill, the House started moving a bill that would allow select districts the ability to bring all students back for in-person learning.

One day later, on March 10th, Cooper and legislative leaders announced a compromise to bring students back to classrooms. Under the plan, elementary schools had to return students to classrooms under plan A, and districts had the option of having students in grades 6-12 in class under either plan A or plan B. The compromise took the form of legislation, which quickly cleared the General Assembly and was signed by Cooper. Thus, nearly one year after schools were closed due to COVID-19, state leaders ordered them almost fully reopened.

Summer learning

A big focus of concern for state leaders was dealing with the aftermath of a year and half worth of schooling that was anything but normal thanks to COVID-19. One of lawmakers’ first attempts to deal with this came in February, when House Republicans put forward a bill that would require every district to offer a summer program focused on at-risk youth to help students catch up on their schooling.

“If we don’t do this right, North Carolina will pay for decades,” said House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, at a press conference announcing the legislation.

The legislation did not allocate money to districts for the program. Instead, lawmakers said that $1.6 billion in federal COVID-19 relief that was being sent to districts could be used. The bill passed the full General Assembly in April and was signed soon after by Cooper.

Lawmakers also ultimately passed a bill that, among other items, appropriated $40 million of the $1.6 billion in federal COVID-19 relief funding to fund summer programs. While Moore initially said districts should use some of their portion of those funds to pay for the program, he ultimately appropriated the money from the 10% of the federal relief funds that the state is allowed to spend how it wants. Read more about that bill here.

EducationNC also talked about the summer learning program in an article about how a bill becomes a law and goes into action. Read that article here.

Here is a look at the summer program from EdNC’s Rupen Fofaria.

Read to Achieve

Since 2018, when a Friday Institute study on Read to Achieve found that it had failed to improve reading proficiency for students, the state has been trying to reform it. The Senate first tried in 2019 with a bill that was ultimately vetoed by Gov. Cooper.

In late March 2021, the Senate tried again. That bill required the training of pre-K and elementary school teachers in the science of reading and new literacy instruction standards.

One of the findings of that 2018 Friday Institute report was that Read to Achieve was implemented differently in districts around the state, so the 2021 bill mandated one approach be used in all districts.

EdNC’s Rupen Fofaria has a breakdown of both the bill and the history that led to it, which you can read here.

Cooper ultimately signed the bill into law in April.

“Learning to read early in life is critical for our children and this legislation will help educators improve the way they teach reading,” Cooper said in an email statement. “But ultimate success will hinge on attracting and keeping the best teachers with significantly better pay and more help in the classroom with tutoring and instructional coaching.”

Posting lesson plans online

May brought a couple of bills that rubbed many educators the wrong way. The first bill, titled “An act to ensure academic transparency,” would force schools and districts to make available to the public information on what instructional materials and activities are being used in classrooms.

Rep. Hugh Blackwell, R-Burke, a primary sponsor of the bill, said in an education committee that when parents are active in their children’s education, students have better outcomes, and this legislation would help parents have more information to enable them to be more engaged.

“This is one of those efforts to say, ‘We’re going to make a little extra effort … to try to make this as simple as possible while still providing the transparency so that parents can be aware of what is being offered to their students,’” Blackwell said.

Rep. Graig Meyer, D-Orange, did not agree.

“This just seems like a pretty large burden to put onto educators,” he said in committee, adding later: “This feels like a heavy-handed element of government.”

While the bill made it through the House, it stalled in the Senate without ever getting a hearing in committee. The House then included a similar proposal in their budget plan, but that provision did not make it into the final budget compromise between Gov. Cooper and legislative Republicans.

Critical Race Theory

House Bill 324, entitled “Ensuring Dignity & Nondiscrimination/Schools,” said that educators could not “promote” the following concepts:

- “One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex.

- “An individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

- “An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of his or her race or sex.

- “An individual’s moral character is necessarily determined by his or her race or sex.

- “An individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.

- “Any individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.

- “The belief that the United States is a meritocracy is racist or sexist or was created by members of a particular race or sex to oppress members of another race or sex.”

Many took to calling this bill a critical race theory bill, though nothing in the legislation used the term critical race theory. Nevertheless, leaders such as Speaker Moore said the bill took aim at critical race theory in schools.

Opponents of the bill, such as Rep. James Gailliard, D-Nash, said the bill “keeps history out of” schools and that, contrary to the title, it ensured discrimination.

The bill passed the House fairly easily in May. In July, the Senate released its version, with new definitions of the word “promote” and six additional concepts that couldn’t be promoted in schools:

- “The United States was created by members of a particular race or sex for the purpose of oppressing members of another race or sex.

- “The United States government should be violently overthrown.

- “Particular character traits, values, moral or ethical codes, privileges, or beliefs should be ascribed to a race or sex, or to an individual because of the individual’s race or sex.

- “The rule of law does not exist, but instead is a series of power relationships and struggles among racial or other groups.

- “All Americans are not created equal and are not endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- “Governments should deny to any person within the government’s jurisdiction the equal protection of the law.”

This version passed the Senate in August, then went back to the House where lawmakers concurred with the changes the Senate made. It then went on to Gov. Cooper, who vetoed it. Lawmakers did not to try to override the veto, as Republicans don’t have the numbers to override gubernatorial vetoes without the help of Democratic lawmakers, and there likely wasn’t any help there to be had.

In vetoing the bill, Cooper said the following:

“The legislature should be focused on supporting teachers, helping students recover lost learning, and investing in our public schools. Instead, this bill pushes calculated, conspiracy-laden politics into public education.”

Testing exemptions and masking votes

One bill that passed over the summer, SB 654, brought some much-needed relief to public schools but also some problems for local boards of education.

During the 2019-20 school year, both the state and federal government gave public schools exemptions from having students take their year-end tests due to COVID-19. But the federal government made clear that wasn’t going to happen in the 2020-21 school year, so students took their tests as required last spring.

The federal government did, however, waive the requirement that the state calculate some of the accountability measures North Carolina typically produces based on those tests — measures such as school letter grades, school report cards, and low-performing schools designations. State statutes did, however, still require those measures, so the Department of Public Instruction and the State Board of Education had been looking for a state waiver from lawmakers all summer.

That finally came down in SB 654. However, the bill, which Cooper signed in late August, also included a requirement that local school boards vote on their mask policies once a month. That meant that every month, district school boards had to meet to discuss whether or not children had to wear masks, and these meeting drew angry parents.

In September, the North Carolina School Boards Association reached out to Gov. Roy Cooper and lawmakers asking for help with school board threats. Specifically, they were asking lawmakers to change the requirement that districts revisit their mask policies every month.

At the time, Lauren Horsch, communications adviser to Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, said: “That some people are protesting decisions of their elected leaders is not legitimate grounds to change a law.”

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt, State Board of Education Chair Eric Davis, and Vice Chair Alan Duncan released a joint statement in September about safety concerns at district school board meetings.

“Our schools and district buildings should remain safe havens, and these acts of aggression cannot be tolerated. Our school board members and local leaders should not be threatened,” the statement read. “Especially in times of disagreement, we should act with civility and respect for our teachers, local boards, superintendents, and school staff who are doing their best throughout this unprecedented time to lead, guide and educate our students.”

The National School Boards Association sent a letter to the federal government asking for help dealing with “threats of violence and acts of intimidation” at local school board meetings across the country, and the North Carolina School Boards Association ended up severing ties with the national organization. Ultimately, the mask-voting requirement was never repealed.

Read all about that below.

Other items of note

A slew of calendar flexibility bills were filed by lawmakers, and some even passed a chamber, but none of them ultimately went anywhere. Calendar flexibility would allow districts more say over when the school year starts and stops. Many districts say they need this flexibility to deal with a host of problems, including issues arising from inclement weather, being forced to hold semester exams after winter break, and the need to align local public school calendars with those of community colleges.

There is large-scale bipartisan support for calendar flexibility, but advocates say that the tourism industry holds up legislation because businesses that rely on student workers over the summer don’t want districts to cut into their season.

A bill that changes standards of student conduct in North Carolina schools passed the House but not the Senate. It then made its way into the House budget proposal but did not make it into the ultimate compromise budget.

The most significant change the bill tried to make is removing from current law the following examples as things that should not be considered serious actions on the part of students:

- Inappropriate or disrespectful language;

- Noncompliance with a staff directive;

- Dress code violations; and

- Minor physical altercations that do not involve weapons or injury.

This is an important distinction because long-term suspensions and expulsions in public schools are supposed to be limited to “serious violations” of student conduct codes.

In 2011, legislation declared that these were not serious actions out of a recognition that not having students in school can contribute to “behavioral problems, diminish academic achievement, and hasten school dropout.”

A House bill that would let teachers take personal leave without having to pay the cost of their substitute teacher passed the House but not the Senate. It was ultimately included in the compromise budget.

Previously, if a teacher took personal leave on a day when they had to be in the classroom, they were responsible for covering the cost of the substitute teacher. Under the budget, however, teachers are not responsible for covering the cost of a substitute if they provide a reason for taking personal leave.

Along with the budget, those are some of the major pieces of legislation the General Assembly took a look at this session. Read our in-depth look at the two-year spending plan below.

What happens next?

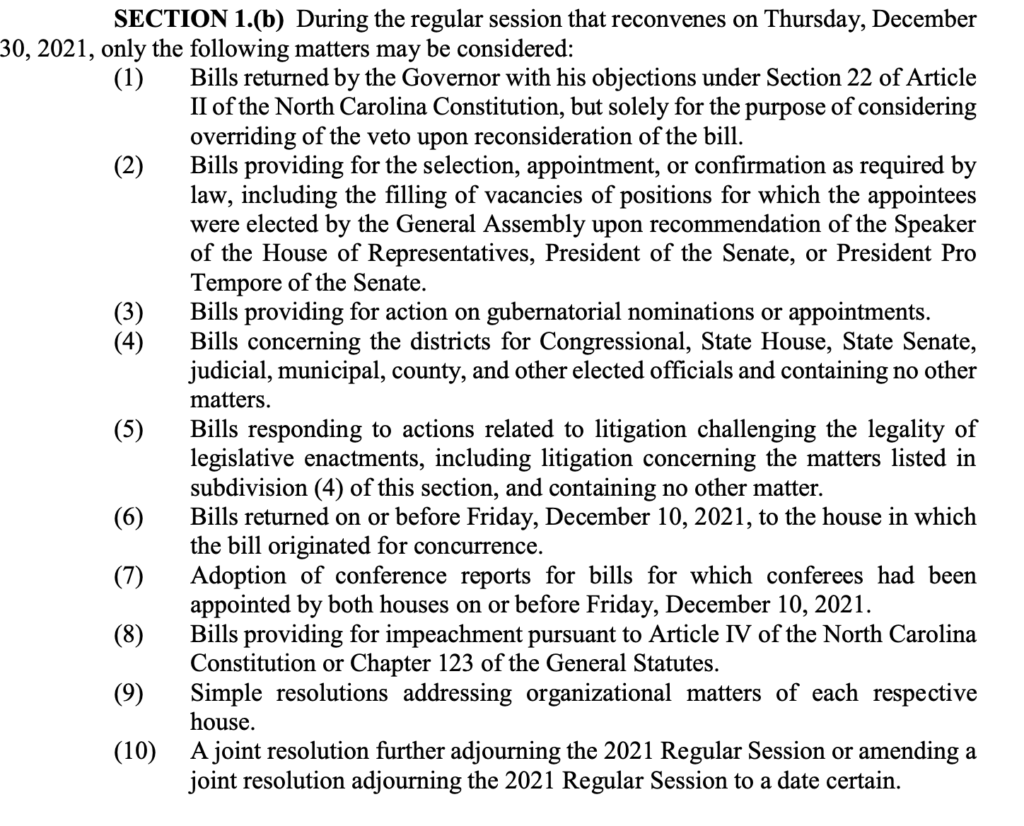

The legislature passed an adjournment resolution that ends session Dec. 10th but brings lawmakers back Dec. 30th. But their return has restrictions, which are as follows:

It’s also important to remember that legislation that impacts the budget or passed at least one chamber this session but not the full legislature can still be considered in next year’s short session.

Recommended reading