After years of discussion by state agencies about the science of reading, the General Assembly last week ratified a bill mandating that instruction be based on this body of research. It passed both the Senate and House with nearly unanimous support in just three days.

Then came the editorials.

One said the bill, called Senate Bill 387, means an emphasis on phonics that wouldn’t work. Another called it a “slap-dash, rushed approach to dealing with critical issues.” Yet another co-signed both of those assertions.

Kymyona Burk chuckles when she hears that. She experienced this eight years ago when, as Mississippi’s literacy director, she was charged with implementing a 2013 law mandating that reading instruction be grounded in the science of reading.

“Your first job is to get buy-in, but that can be hard — you should have seen the headlines when we were going through it all,” Burk told EdNC in 2019, during reporting for this project on the science of reading.

On Monday, she reflected on that and on what’s happening in North Carolina.

Most people in Mississippi in 2013 were unfamiliar with the science of reading, she said. Teachers and administrators bought in, once her department and other state leaders traveled to talk with them about what the new law meant. Families bought in, she said, when they saw the results — Mississippi’s third-grade reading proficiency scores rose and remained above 80% starting three years after the law was put into effect.

“We just could not ever say we were too busy,” she said. “[We had to] stay engaged when it came time to talking to anyone who we need to talk to.”

Senate Bill 387 now awaits a decision by Gov. Roy Cooper, who can exercise his veto power anytime before next Monday, April 12. In the meantime, EdNC reached out to educators and stakeholders to better understand what this bill means.

Did the General Assembly rush to pass it?

The backbone of the bill — the science of reading itself — and many of its provisions have been discussed by the State Board of Education, UNC System, and Department of Public Instruction for years.

In 2017, the UNC System’s Board of Governors passed a Resolution on Teacher Preparation. It asked eight literacy fellows from UNC institutions to develop a common framework for instruction in teacher preparation. This framework, published in February, draws from the body of research that’s called the science of reading, and it proposes teacher training in eight concepts: print, language, phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics/orthography/automatic word recognition, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing.

That framework, the report says, aligns with recommendations from a State Board of Education literacy task force. That task force was convened in late 2019, after several months of discussion during State Board meetings, and in June 2020 delivered its recommendations — which define high-quality reading instruction as grounded in the current science of reading. Kim Winter, a task force member and dean of Western Carolina University’s college of education and allied professions, says every word in that definition is important. Here it is:

High quality reading instruction is grounded in the current science of reading regarding the acquisition of language (syntax, semantics, morphology and pragmatics), phonological and phonemic awareness, accurate and efficient word identification and spelling, world knowledge and comprehension. It is guided by state-adopted standards and informed by data so that instruction can be differentiated to meet the needs of individual students. High quality reading instruction includes explicit and systematic phonics instruction, allowing all students to master letter-sound relations so that they can understand the meaning of increasingly complex texts.

Much of this definition, though not all, is in the bill that passed last week.

Throughout this period, the DPI has also been heavily involved, working independently as a B-12 interagency literacy committee starting in 2019, as well as collaboratively with the State Board’s task force, where several members of the DPI committee also served.

The DPI committee gathered input from more than 1,600 educators across the state. In September 2020, the committee’s work resulted in the state’s 2020 Comprehensive Plan for Reading Achievement. The plan’s definition of high-quality reading instruction is nearly identical to that of the State Board task force. The plan also devoted 10 pages to some of the reading research.

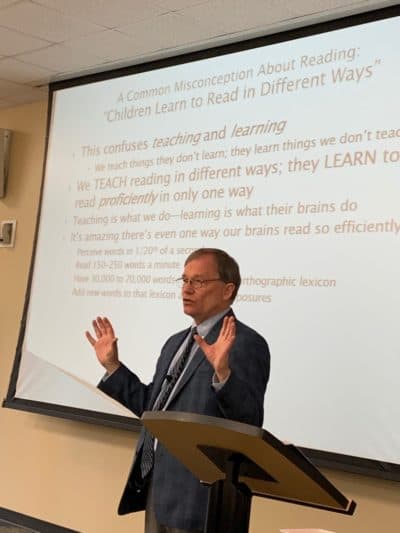

Is the science of reading about emphasizing phonics?

The science of reading is a body of scientifically based research. It tells us how brains learn to read and the best practices for instruction.

“The science of reading is not just about what needs to be covered,” Winter wrote in an email to EdNC, “it is also about how it is taught.”

The research includes what is known as the “simple view of reading,” which says that reading comprehension is the product of both decoding ability (which includes phonics, but also much more) and language comprehension. The science also says decoding and language comprehension should be taught systematically and explicitly.

That’s because our brains aren’t wired to learn to read. Neural pathways need to be developed, through such strategies as alternating hard vowel sounds (to stimulate synapses on one side of the brain) with soft vowel sounds (to stimulate synapses on the other side). A simple phonics emphasis doesn’t necessarily include that level of brain engagement.

The science also goes beyond reading comprehension to include writing instruction, as well.

“The concept of the ‘science of reading’ and the actual teaching of reading are complex,” Winter wrote.

In other words, too complex to be reduced to phonics.

Does SB 387 mandate a curriculum or program?

Carrie Norris, the curriculum director for Transylvania County Schools, said that the science of reading training happening in her district is making her teachers smarter than any curriculum they use, but that there’s no “science of reading curriculum.” She likes the bill’s support of the science of reading because knowledge from the research empowers her teachers.

“I like the fact that it reiterates the importance of understanding WHY we do WHAT we do in our reading instruction,” Norris wrote in an email to EdNC. “Without teacher understanding and knowledge, it is too easy to sway from instructional strategies without truly understanding the way the brain learns to read proficiently.”

Burk said part of the trouble with the current approach in many schools nationwide is that it’s overly dependent on curriculum. That makes it hard to tailor lessons for children at different levels of proficiency, she said.

“That’s why we invested in teachers,” she said about Mississippi’s approach to implementing its science of reading law, “not programs.”

What will the science of reading mean for the state’s most vulnerable students?

At Hill Learning Center, Executive Director Beth Anderson works with students who learn differently. Like many programs working with striving readers who have some learning disability, Hill uses methods aligned with the science of reading.

“Even though many methods for teaching reading have developed over time, Science of Reading shows us that all young students’ brains learn to read proficiently in a very consistent way,” Anderson wrote to EdNC. “In fact, when reading instruction is aligned with cognitive science, nearly 95% of students can learn to read with systematic, sequential, explicit, and cumulative reading instruction aligned with the science of reading.”

Burk said Mississippi’s results led her to believe the approach grounded in the science of reading is most effective for vulnerable learners. She points to her state’s 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress scores (2019 tested the first cohort of Mississippi fourth-graders who began kindergarten after the state law was implemented).

“Nationally, our students from our low income families, whether Black, white, or Hispanic, achieved higher scores than the national average,” she said. “I think that, again, this speaks to what we’ve been able to do as a state that has focused on the science of reading.”

What about the bill’s mandate for one vendor?

Several education professionals contacted by EdNC voiced concerns about the bill mandating use of one vendor for certain training.

The bill mandates that pre-K through fifth grade teachers receive training pursuant to a separate law, Session Law 2021-3. That law, which was House Bill 196, was drafted with consideration from stakeholder requests. For DPI, it allocates $12 million of federal relief funds for use with Voyager Sopris Learning, which owns the Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training program.

“It’s not a silver bullet solution, or the only option,” Anderson wrote about LETRS. “And mandating the same training for every LEA does not honor their context, investments they have already made, or the potential for local sustainability. Districts and charters are at different points in their science of reading journey and understanding.”

The bill also requires training in the science of reading — but without mandating a vendor — for teacher candidates who want to work in elementary classrooms or teach students with disabilities. Winter said funding at the educator preparation level could be better allocated to supporting pedagogy rather than one-off training, like investing in work involving the UNC System’s literacy framework.

“Do I support legislated funding that provides assistance to and allows for intensive collaboration in our efforts to ensure all students learn to read? Of course,” Winter said. “And I’d be willing to bet that so do every one of my colleagues around the state. Do I believe legislation should dictate training by name and vendor? No. The last thing we need is to adopt prescriptive and regimented curriculum that teaches us to believe training sessions will help develop conceptual and deep knowledge.”

Burk said Mississippi used LETRS and says the training was critical to the state’s improvement in reading instruction. She said that Mississippi took bids for professional training programs aligned with the science of reading and that the selection committee chose LETRS because the training was substantive, well-grounded in research, not too overwhelming, and the vendor could do statewide training for thousands of teachers and administrators.

Anderson called LETRS “a very comprehensive and high quality training” that she “would love to see widely and appropriately implemented.” But for some districts, it might be too much, too soon. She pointed to the DPI Exceptional Children Division’s North Carolina State Improvement Project, which offers a Reading Research to Classroom Practice training. This training is the first by any state education agency to be accredited by the International Dyslexia Association.

“If the state is committed to mandating LETRS universally,” she said, “since LETRS is a more in-depth training that takes longer, they could consider leveraging the Research to Classroom Practice course over the summer and beginning of next school year to give the teachers strong foundational knowledge … and then launch LETRS training. This approach would also buy time for approving alternative vendors/trainings should the state want to do so.”

Disability Rights NC (DRNC), a legal advocacy agency that fights for the rights of students with disabilities, said it likes the idea of using a single vendor because that will help with data analysis.

“We think a single statewide program will allow in-depth analysis of progress – or lack of progress,” DRNC wrote to EdNC. “This will help DPI and local school districts identify which students are not making adequate progress and why. We need a few years of ‘apples to apples’ data for that to happen.”

Does the bill include adequate supports for its mandates?

Teachers have voiced concern over the cost of materials, such as decodable readers that help students solidify decoding skills. That isn’t covered in this bill.

Teachers have also asked for more teacher assistants. Though that also isn’t covered in this bill, it is in another bill still sitting in the General Assembly.

Many educators we heard from focused on two supports missing from the legislation: In-school coaches and ongoing professional development for educators.

“My emphasis is on continuous professional development for teachers to build capacity in every school,” said Roya Qualls Scales, a literacy professor at Western Carolina and one of the eight UNC System literacy fellows. “Knowledgeable teachers who are well-equipped with a variety of strategies for teaching reading are more able to tailor their reading instruction to meet every students’ learning needs. When given the resources and flexibility to make instructional decisions based on their students’ needs, teachers can help their students make great strides.”

Crystal Hill, who co-chaired the State Board’s literacy task force, said coaches were critical to success if SB 387 becomes law. She said teachers will receive a tremendous amount of research and information in training, and she worries that sending them into classrooms to put that information into practice without help is unfair.

Burk said her experience supports that notion. Mississippi’s law included funding for coaches, but not enough for one in each school. Before she left to become a policy director at ExcelinEd, she said, there were 80 coaches covering 181 schools.

“How did we ensure that we’re not putting this (research) on teachers without the support that they need in order to do this effectively, successfully?” Burk said. “I think our coaches being on the ground assisting our teachers in transferring that knowledge from theory to actual practice in their classrooms helped a great deal. And it actually sped up the gains that we were able to see in such a short period of time and then be able to sustain.”