|

|

Michelle Thigpen walks out of the media center at Southwest Elementary in High Point, apologizing for a mess that doesn’t seem to be there.

“We’ve got to piecemeal the stripping and waxing with summer school going on,” says Thigpen, an 18-year veteran principal, as she walks down a tidy hallway. It doesn’t take long to realize she runs a tight ship and has lofty standards.

Down the hall, the rooms are abuzz with students. Lots of them. At first glance, you might think they’re at camp — what with all the games and laughter. But there’s learning happening. Thigpen has the math and reading scores to prove it.

“We are seeing growth,” she says, adding that she expects growth. Last year, her school received an A for performance and a 100 for growth on the state report card. “I expect my staff and myself to give the students our best every day, and we expect our students to give their best every day — so that they can be successful.”

VIDEO: A peek inside summer school at Southwest Elementary

In a typical year, Southwest Elementary wouldn’t house its own summer school, but this year is different.

Usually Guilford County Schools designates one site to host students from three or four schools. In past years, Thigpen said, she’d expect summer enrollment of 30 to 40 of her kids. The school has about 800 students, the most of any elementary school in GCS (which is the state’s third-largest district).

This summer, though, North Carolina students spent most of this past school year in remote or hybrid learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic. To bolster in-person learning opportunities, the General Assembly passed House Bill 82 in April, which mandated that every district offer at least 150 hours or 30 days of summer school.

At Southwest Elementary, 176 kids attended.

“It’s very, very important that we stay on top of the individual needs of our students and that we remove any barrier they may have,” Thigpen said. “I expect us to do that, COVID or not. But with COVID, it was even more important that we were doing that intentionally. And the teachers that are here, 99.9% of them believe in that.”

Thigpen is high on “collective efficacy” — which she said is the belief among educators at her school that they can do anything together. Last year, that meant reaching and teaching kids, whether they could arrive in person or not. Every grade-level end-of-grade score she has received so far suggests the teachers succeeded. All of them went up, she said, adding that she’s awaiting fourth- and fifth-grade reading results.

Despite strong scores, administrators at Southwest Elementary pushed hard to get as many students as possible enrolled in summer school. They wanted to keep pushing kids toward mastering content. Plus, she said, consistency over the summer helps her students — and teachers.

“I know it’s hard,” she said of her teachers’ challenges. “I know they’re exhausted, and they haven’t had any down time. But it’s also helped us so that we can keep digging deeper and keep providing that feedback and coaching so that we can be even stronger for August.”

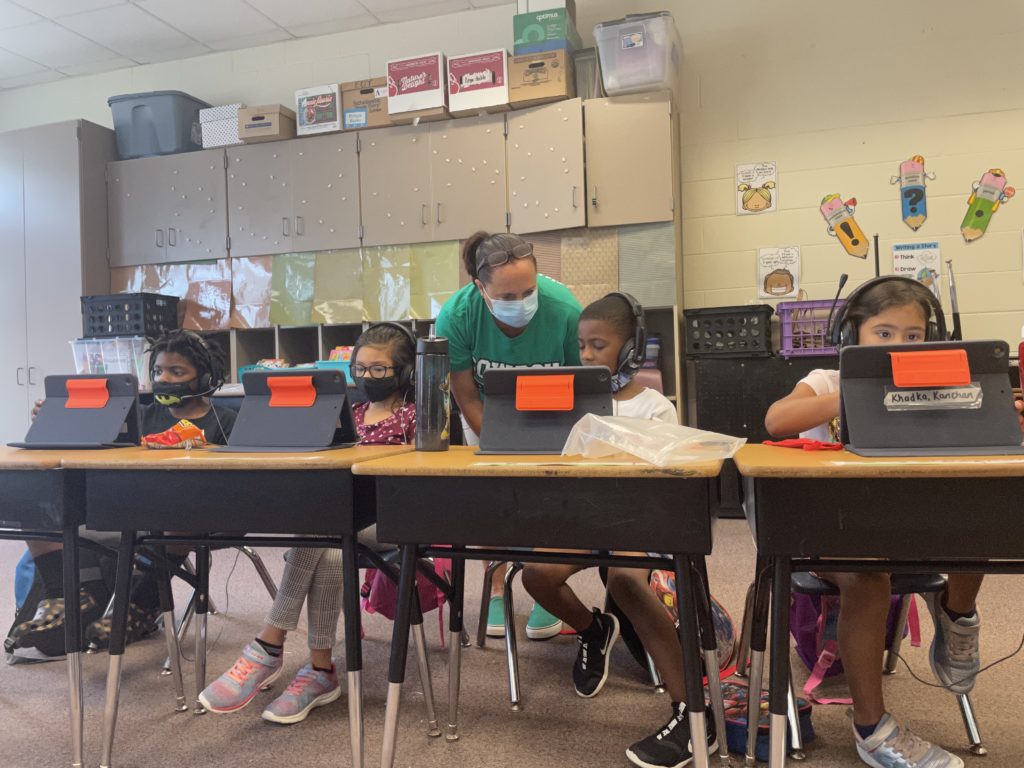

To make sure students got the most out of the summer school experience, administrators and teachers at Southwest went through every student’s end-of-year NWEA reading and math scores to find areas for improvement. They then grouped students by skill gaps and focused on bridging those for each student.

“We have to stay focused on teaching the skills and standards,” Thigpen said. “That’s the most effective thing to do — making sure you, as the teacher, know what the students need to be successful with, to completely master that skill and standard.”

After each three-week summer session, teachers tested the students again to see whether they made gains. Thigpen said she’s processing the data now, and she’s seeing growth.

Guilford County Schools also paid tutors to work at elementary schools for summer camps. The tutors were from area high schools and worked one-on-one with elementary students throughout the day. Southwest hosted two tutors from nearby high schools.

Thigpen said teachers focused on social-emotional learning, too, and used the opportunity to spend extra time with students who have learning differences.

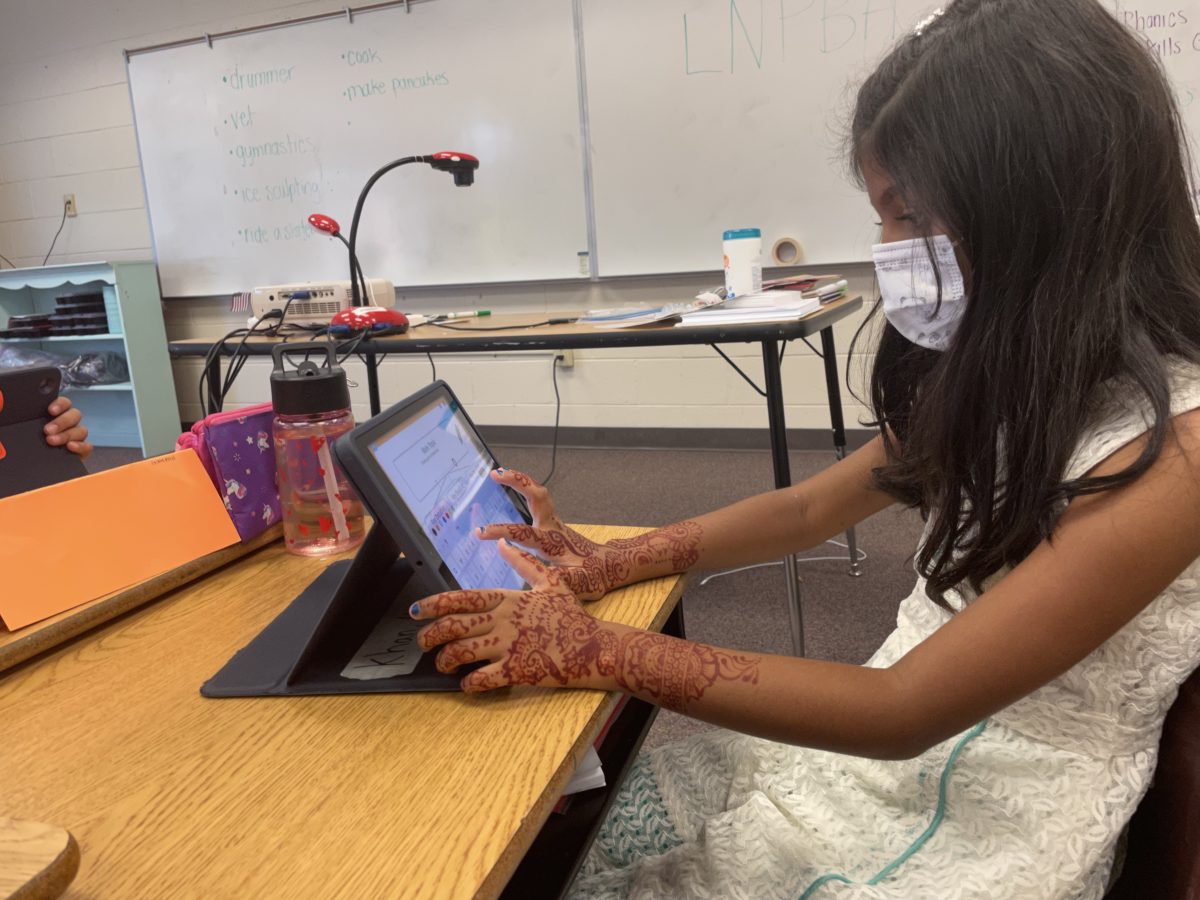

The district received $3.3 million in COVID-relief funds for its summer learning program. It received about $40 million in total COVID-relief funds, which allowed it to provide physical resources to summer school students. Students take home three books and get a device — iPads for K-3 students and Chromebooks for fourth- and fifth-graders.

“It’s enabled us to be even more intentional with meeting the needs of our students,” Thigpen said.

While the occasional student arrives less than eager to be in school over the summer, Thigpen said, kids have mostly shown up with smiles on their faces. And the teachers have, too.

“Something happens and you realize that you have to make the most of each and every single day,” she said. “I preach that and try to live that by example for everybody — that a day that we do not give our students our best is a day gone wrong.”