|

|

Contents

- Understanding the budget

- The budget process

- Salary increases

- Districts held harmless

- Federal COVID-19 funds

- School choice provisions

- Early childhood education

- N.C. education lottery

- What about Leandro?

- Innovative School District

- Broadband

- What didn’t make it into the budget

- Other items of note in the budget

- Reactions from education leaders

This long session of the General Assembly has given new meaning to the term “long session.” More than four months after state law says North Carolina needs to have a budget, Democrat Gov. Roy Cooper and the Republican-led General Assembly finally agreed on a spending plan that includes $25.9 billion in 2021-22 and almost $27 billion for 2022-23. The plan quickly passed and was signed it into law.

The agreement is particularly momentous given the fact that the state hasn’t had a budget since 2018. Cooper vetoed the first two Republican budgets after he took office in 2016, but it wasn’t until the 2018 mid-term elections that Democrats gained enough seats in the General Assembly to uphold his vetoes.

As a result, Cooper’s veto of the 2019 Republican biennium budget — which he said was inadequate in terms of education spending (particularly on teacher salaries) and Medicaid expansion — was upheld. North Carolina has not had a budget until now.

Going into 2021, the state had a surplus of $4 billion. As of Oct. 2021, that number had grown to more than $9 billion in unreserved funds.

Understanding the budget

Each session there is a budget bill, and there is also a companion conference committee report, which provides details on the increases and decreases to the budget.

Here is the most recent version of the budget bill. Here is the most recent version of the conference committee report.

Changes to the education budget can be found in the conference committee report. The K-12 education budget starts on page B-19. Recurring (R) means the dollars will be included in the budget going forward. Non-recurring (NR) means it is a one-time appropriation. If the dollar amount is in parens, then the funds were reduced.

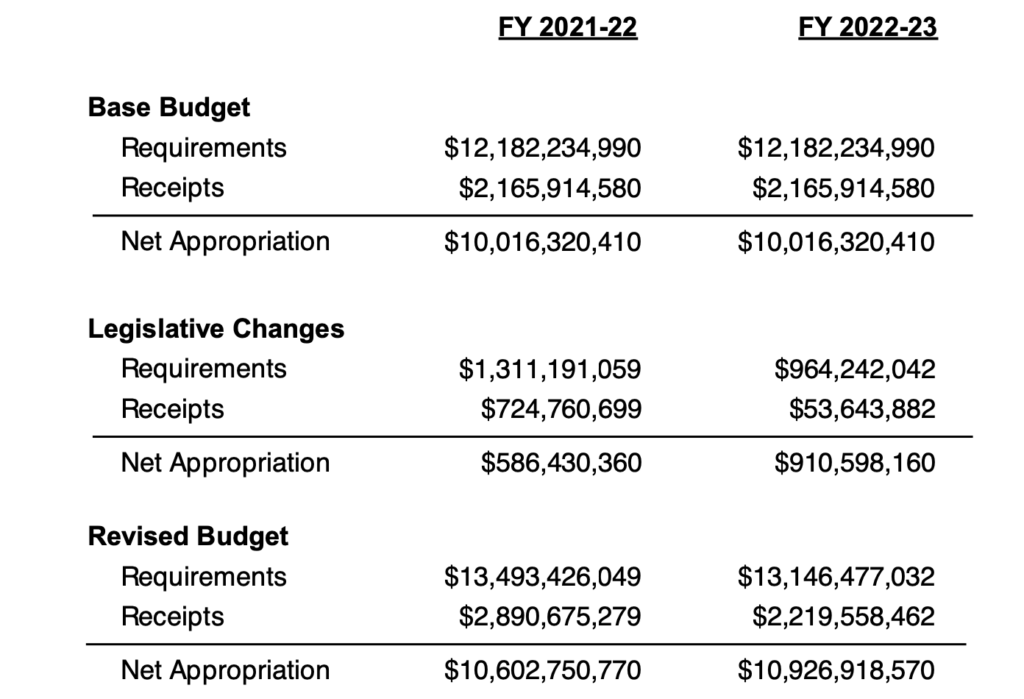

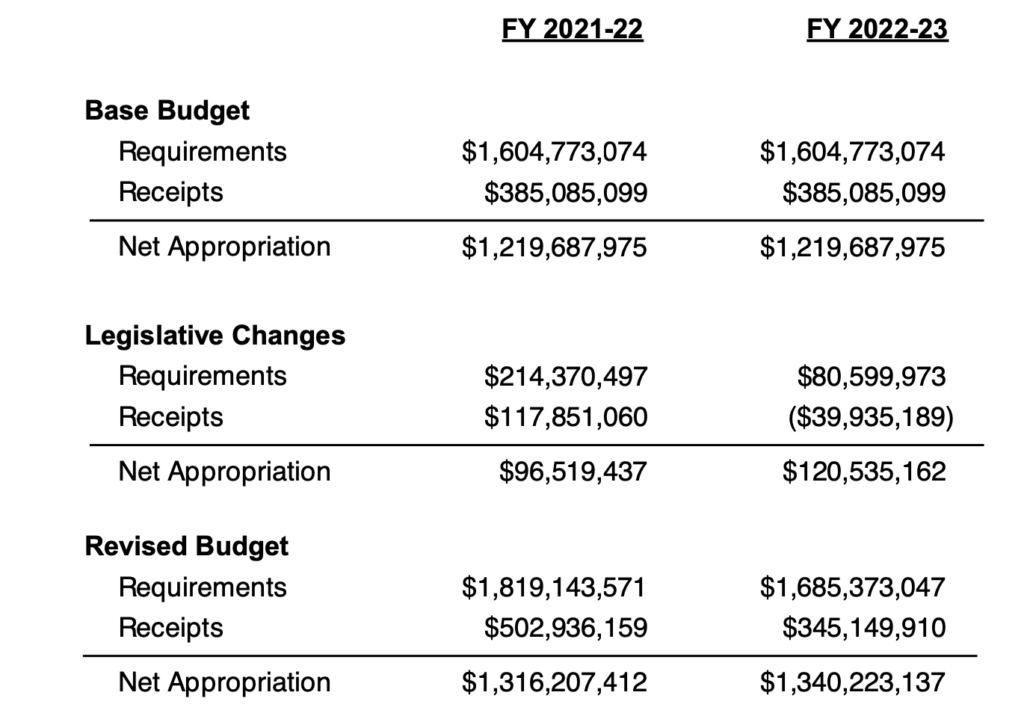

In terms of public education funding, the budget is broken down into K-12 funding, community college system funding, and University of North Carolina system funding.

Looking at just K-12 education, the state is appropriating $10.6 billion in FY 2021-22 and $10.9 billion in FY 2022-23.

Looking at community colleges, the state is appropriating a little more than $1.3 billion in both years of the biennium.

The budget also contains some education items that aren’t included in either of those sections, namely some school choice programs contained in the UNC System budget and child care programs in the Department of Health and Human Services budget. We will cover those later.

The budget process

Gov. Roy Cooper kicked off the budget process in March with his proposal, which included just over $11 billion in K-12 education spending in 2021-22 and $11.65 billion in 2022-23. It also included a roughly 10% average pay increase for teachers and principals over two years (including regular step increases). In addition, teachers, principals, and all public school personnel would have received a one-time bonus of $2,000 in May 2021.

For more detail on the governor’s budget proposal, click here.

The Senate followed up in June with their budget proposal, which included about $10.4 billion in the first year for K-12 and $10.5 billion in the second year. It included a 3% average pay increase over two years (including regular step increases), as well as a $1,500 bonus for any state employee making $75,000 or less and $1,000 for any making more. Teachers would have also gotten an additional $300 bonus.

Principals would have also received a 3% pay raise over the biennium under the Senate’s pay proposal. They would also have gotten the bonuses for state employees, as well as an additional $1,800 bonus.

For more detail on the Senate budget proposal, click here.

The House released their budget proposal in August. It would have appropriated almost $10.6 billion in the first year of the biennium for K-12 education and almost $10.75 billion in the second year. It included an average teacher pay raise of 5.5% over two years (including regular step increases). Principals would have gotten a 1% bump in salary each year of the biennium.

All state employees would have received a $500 bonus under this plan, with all those making less than $75,000 getting an extra $1,000 bonus on top of that. Employees making less than $40,000 would have gotten another $500 in addition to that. And teachers would have also gotten an extra $300 bonus.

For more detail on the House plan, click here.

The big difference this session from the last two was that Republican legislative leaders said they wanted to work with Cooper ahead of a consensus budget in order to head off the possibility of a veto.

As a result, Cooper worked with the General Assembly from the passage of the House budget until November. Just prior to the release of the budget, Cooper sent out the following tweet.

Salary increases

The signed budget includes an average 5% increase in teacher pay, 5% across-the-board pay raises for both principals and community college personnel, and a variety of bonuses for state employees and teachers.

Read more about those in detail, as well as bonuses and a new program that provides funds to help districts supplement the salaries of their teachers, below:

But it’s not just educators getting raises. There is also funding in the budget to provide:

- A $3,500 salary supplement to school psychologists, speech pathologists, and audiologists.

- A $1,000 salary supplement for school counselors.

- An across-the-board salary hike of 5% over two years for district central office and state Department of Public Instruction staff.

- A $1,000 bonus “to match local funds on a 1:1 basis to recruit teachers and instructional support personnel to LEAs receiving funding from the Small County or Low Wealth allotment.”

Districts held harmless

One item of particular concern to districts was whether or not they would be held harmless for Average Daily Membership numbers that came in under projections this school year. ADM is used to determine funding for schools.

Here is DPI’s definition of ADM and how it is calculated:

“The total number of school days within a given term, usually a school month or school year, that a student’s name is on the current roll of a class, regardless of his/her being present or absent, is the number of days in membership for that student. The sum of the number of days in membership for all students divided by the number of school days in the term yields ADM. Average daily membership is a more accurate count of the number of students in school than enrollment.”

Districts receive initial funding based on their projected ADM, but if their actual ADM comes in lower, their budgets could be cut. DPI takes the best of month 1 or month 2 ADM when determining actual ADM.

Last year, the General Assembly held districts harmless for decreases in ADM, which meant a lower-than-projected student population didn’t result in a loss in funding. As of the release of first-month ADM numbers this year, the General Assembly had not acted, and some were concerned.

Those initial ADM numbers showed that districts had rebounded some from the dramatic decreases at the peak of the pandemic, but they hadn’t bounced back to their numbers from 2019.

Kris Nordstrom, senior policy analyst in the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education & Law project, wrote in NC Policy Watch that school districts could have lost up to about $132 million due to budget adjustments if they weren’t held harmless by lawmakers.

Fortunately, the budget includes language holding districts harmless for decreases in enrollment.

Read more about this year’s first- and second-month ADM numbers in the article below.

One item to note, however, is a provision in the budget that directs the State Board of Education to figure out a formula for using full-time equivalency as a measure for per-pupil funding rather than ADM. Full-time equivalency, also known as FTE, is a way to measure the amount of course hours taken by students to fund, typically, institutes of higher learning, such as universities and community colleges.

The provision directs DPI to report to lawmakers the FTE of public school students on Oct. 15th of each year, and it says that the State Board must report to lawmakers by April 15, 2022 on their FTE formula.

A move to funding based on FTE rather than ADM would be a dramatic departure from the way education has traditionally been funded in North Carolina.

Federal COVID-19 funds

The state budget also allocates a portion of the $3.6 billion sent relatively recently to North Carolina school districts for COVID-19 relief. Under federal guidance, the state is able to hold back 10% of that funding, and the budget spends what’s left of that 10%.

Here are some of the main ways the budget spends that roughly $360 million:

- $20 million to make sure every “public school unit” — districts, charter schools, lab schools, etc. — gets $400 per pupil in federal money.

- $36 million for grants to public school units for COVID-19 related needs, “including for in-person instruction summer programs to address learning loss and provide enrichment activities.”

- $36 million for COVID-19 related needs “including after-school and before-school programs that incorporate supplemental in-person instruction to address learning loss and provide enrichment activities.”

- $37.5 million for teacher and principal professional development in the science of reading.

- $13.5 million for the North Carolina Education Corps.

- $21 million for contracts with groups for technology to help with cyberbullying, suicide prevention services, and more.

- $18 million “to provide coaching support and professional development for principals and school improvement leadership teams.”

- More than $6.6 million to help districts “to identify and locate missing students.”

- $100 million for a one-time $1,000 bonus for teachers (covered in salary/bonus article mentioned above).

School choice provisions

The budget includes $30 million in new funding for the Opportunity Scholarship Program, which gives state funds to students to be used for private school. It also mirrors language in a failed Senate bill that would increase the income eligibility amount from about 150% of the income required to qualify for free-and-reduced-price lunch to 175%, which equates to about $85,000 a year for a family of four.

It would also increase the amount of money Opportunity Scholarship recipients get to up to 90% of state per-pupil funding. The current average state per-pupil allocation is $6,586, according to DPI staff. That means students using Opportunity Scholarships could get about $5,900 per year, up from $4,200.

The budget also increases the amount of money the General Assembly is automatically putting into the program each year.

Originally, lawmakers put into the base budget increases of $10 million to the program each year until 2026-2027. In this budget, lawmakers extend the payouts until the 2031-2032 school year and increase the yearly contribution to $15 million. The amount of money held in reserve for the program will reach more than $240.5 million by 2031-2032.

The budget also increases funding for two other school choice programs, the disabilities grant and education savings account programs, and combines them into one program. Both programs give public funds to students for use in a non-public school setting.

Early childhood education

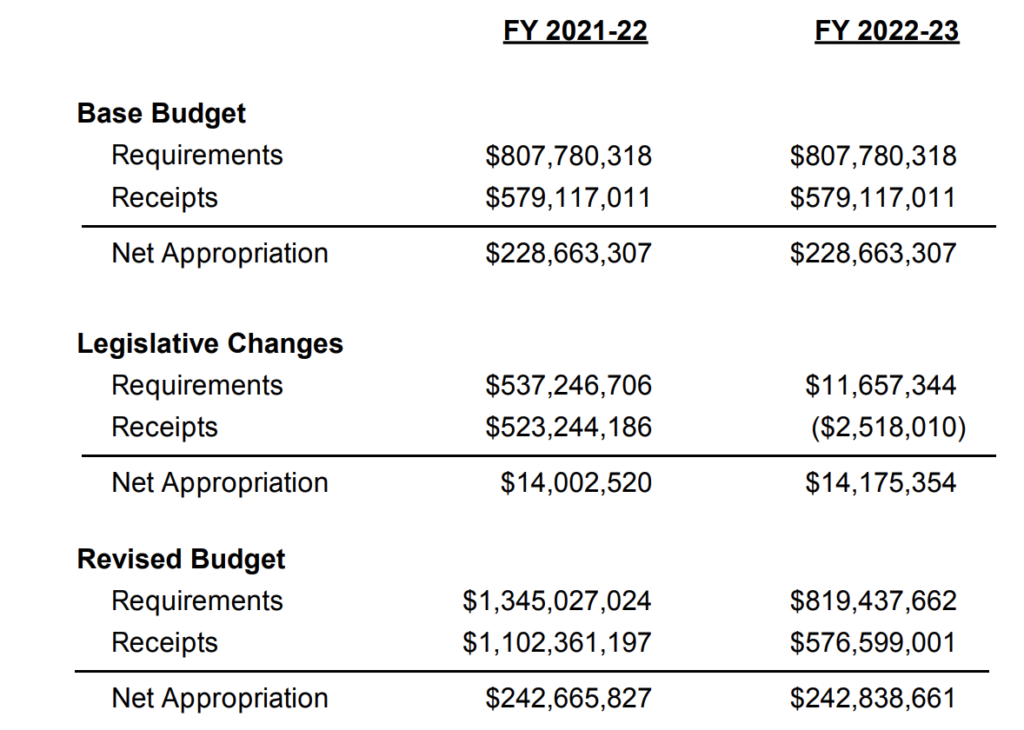

The budget appropriates almost $243 million in each of the next two fiscal years to the Division of Child Development and Early Education, which falls under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Early care and education programs still largely rely on private tuition, but most public funding that does exist — for things like subsidy assistance and the state’s NC Pre-K program — is overseen by DHHS. In addition to the state’s appropriation, DHHS receives funds from the federal government through sources such as the Child Care and Development Fund and the Preschool Development Grant.

The budget did not include two big funding asks from early education advocates: to expand educator wage supplements and to pay providers higher rates to serve children through the subsidy program.

Funding for teachers in all 100 counties to access the WAGE$ program, which gives education-based supplements if teachers agree to stay at their programs, made it to the House’s budget proposal but not the final budget.

“We are most disappointed to see the lack of funding for early educators,” reads a statement from the North Carolina Early Education Coalition. “Child care teachers are the workforce behind the workforce, and they have been on the frontlines of the COVID-19 crisis since day one. North Carolina is facing an unprecedented workforce crisis due to poverty-level wages, and professional compensation is needed now to attract and retain a high-quality workforce.”

In terms of pandemic recovery, the budget did allocate $502 million in federal American Rescue Plan funds for the following purposes:

- $274 million to support families on the child care subsidy waitlist, to cover parents’ fees through Dec. 2021, and to modernize licensing and subsidy management technology.

- $207.7 million to “build the supply of qualified child care teachers” through bonuses and other teacher pipeline programs like apprenticeships, stackable courses, and fast-track programs.

- $16 million in federal Child Care Entitlement to States grant, which unless designated, becomes part of the child care subsidy assistance program.

These relief funds were part of a larger federal pot of money for North Carolina child care. Another $805 million went directly to DHHS. The department is distributing those funds to child care facilities through stabilization grants over the next 18 months.

The budget allocates another $20 million in federal funds to cover start-up costs for new child care centers and NC Pre-K classrooms, with a priority on adding facilities in child care deserts and high-poverty areas. The funds can also be used for increasing program quality and capacity.

When it comes to NC Pre-K — the state’s preschool program for 4-year-olds in low-income families — the budget increases the rate the state pays child care centers by 2% in each of the next two fiscal years. It’s the intent of the legislature that these extra funds be used “to address disparities in teacher salaries among teachers working in child care centers versus those working in public schools or Head Start centers.”

The budget also gives $10 million in recurring funds in each of the next two years to Smart Start, the statewide network of local partnerships that administer early childhood funds and programs.

N.C. education lottery

Money from the N.C. education lottery’s school construction fund can be spent on both new construction and repairs to existing structures. Republicans in the General Assembly added a Needs-Based Public School Capital Fund (NBPSCF) to the education lottery in 2017-18. This was specifically for the construction of new facilities in low-wealth counties (Tier 1 or 2) and required matching funds from those counties.

The budget makes significant changes to the NBPSCF, including changing eligibility (Tier 2 is no longer automatically included) and allowing counties to use the funds for “enlargement, improvement, expansion, repair, or renovation of classroom facilities at public school buildings within local school administrative units located in the county.”

DPI’s website for the PSBCF and NBPSCF now hosts the following statement:

“The 2021-23 State Budget (SL 2021-180) includes significant changes to the Needs-Based Public School Capital Fund (NBPSCF). DPI is required to incorporate these changes into program guidance materials prior to opening the 2021 NBPSCF application period. When the application and submittal schedule is established, this announcement will be updated.”

Typically, the due date for grants from these funds would be Dec. 20, 2021. No updated due date has been provided by DPI.

What about Leandro?

Another big question in the minds of many was what the budget would say about the Leandro case. Judge David Lee, the current judge overseeing the decades-long case, ordered the state to transfer about $1.7 billion to fund the next two years of a comprehensive plan aimed at making sure the state was fulfilling its constitutionally-mandated duty to provide all children the opportunity for a sound basic education.

The state controller appealed to the state Court of Appeals to intervene, and they recently ruled in a 2-1 opinion that Lee didn’t have the authority to order the money appropriated. They did say, however, that Lee’s order that the state was obligated to fund the comprehensive plan still stands. But the court said it was up to voters — not Judge Lee — to act if the executive or legislative branches failed to fund the plan.

According to WRAL, Senate Republicans put the amount of “Leandro funding” in the budget at $933 million. Nordstrom, however, puts the number at closer to $761 million in this piece.

The state controller’s filing said the following about the comprehensive plan and the budget:

“It is unclear … what credit, if any, should be given for the funds recently appropriated by the General Assembly and how the funds would be accounted for in the current operation budget.”

Regardless, Lee’s order was to implement the “comprehensive” plan, so it was unlikely that anything substantially short of the targets set forth in his order would have satisfied him or the parties in the case.

The comprehensive plan calls for $690.7 million in 2021-22 and $1.06 billion in 2022-23.

Read the latest on Leandro below:

Innovative School District

This year’s budget will end the Innovative School District. This controversial project was created in 2016 and was intended ultimately to incorporate up to five schools within a “district” of low-performing schools from around the state that for-profit or non-profit charter management organizations could take over and turn around. The program went through many changes since its advent, but it never managed to get more than one school into the district and that school faced tremendous challenges.

According to the budget plan, the Innovative School District will continue to operate its sole school — Southside-Ashpole Elementary School — until 2023-24 at the latest, when it will be returned to the Public Schools of Robeson County.

Broadband

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for high-speed internet connections around the state. The budget includes about $1 billion in non-recurring federal COVID-19 relief for broadband expansion in a variety of programs. Here are some of the bigger ones:

- $400 million for the “Completing Access to Broadband Fund (CAB Fund), a special revenue fund within the Department of Information Technology, for broadband grants to be awarded that meet the criteria in a related provision.”

- More than $349.9 million for grants to expand broadband in rural areas.

- $100 million for costs related to new utility poles and infrastructure “to support rapid deployment of broadband in rural areas.”

- $90 million “to issue targeted grants addressing local infrastructure needs and connecting unserved and underserved households.”

- A little more than $18 million for the Smart School Bus Pilot, which “will allow for enhanced safety protocols and Wi-Fi connectivity on school buses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

- $15 million for broadband access improvement for 25 community colleges in rural North Carolina.

What didn’t make it into the budget

Some controversial items included in previous legislative versions of the budget didn’t make it into the final budget. These include:

- A provision that would have effectively delayed new K-12 social studies standards passed by the State Board of Education this year and created a commission to review the standards over the following year. The standards were controversial and received a split vote from the State Board of Education.

- A provision that would force teachers, districts, and charter schools to post their lesson plans online. The House tried to move a similar bill earlier in the session.

- A provision that would withhold a district superintendent’s pay if a district wasn’t in compliance with legislative requirements about instruction on cursive writing and multiplication tables.

Other items of note in the budget

- $25 million non-recurring for a reserve for 2021-22 to be used when “enrollment of students with disabilities exceeds the original anticipated enrollment of students with disabilities.”

- Funding to ensure that each district in the state has at least one school psychologist.

- A little more than $13 million to increase the Child with Disabilities allotment funding cap from 12.75% to 13%.

- Almost $3 million recurring in both years of the biennium for a transportation reserve fund for homeless children and foster children. The fund “will be used to support the extraordinary transportation costs of qualifying students.”

- An additional $1.9 million recurring for instructional supplies.

- A little more than $1.8 million recurring in both years of the biennium for the state’s Cooperative Innovative High Schools, often called early colleges.

- Almost $9.7 million non-recurring for a grant program “to support students in crisis, school safety training, and safety equipment in schools.”

- $7 million non-recurring in both years of the biennium to create statewide cybersecurity protection for public schools.

- $6.5 million non-recurring in the first year and $5.5 million non-recurring in the second year “to carry out the activities of” the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021.

- $4.6 million recurring in state funds in both years of the biennium for a program that “brings broadband connectivity to all K-12 public school buildings in the State.”

- A little more than $2 million recurring in each year of the biennium to expand the Advanced Teaching Roles program.

- Change to the funding for a program that helps teacher assistants pay for tuition expenses to become teachers from recurring to non-recurring.

- A policy change that allows teachers to take leave without paying for the cost of a substitute teacher

Reactions from education leaders

On Nov. 18, Gov. Roy Cooper signed the budget into law. Here is what he had to say in a statement.:

“This budget moves North Carolina forward in important ways. Funding for high speed internet, our universities and community colleges, clean air and drinking water and desperately needed pay increases for teachers and state employees are all critical for our state to emerge from this pandemic stronger than ever. I will continue to fight for progress where this budget falls short but believe that, on balance, it is an important step in the right direction.”

Gov. Roy Cooper

House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, said the following after Cooper signed the budget:

“Today is a great day for all of North Carolina. Finally, the citizens of North Carolina have a comprehensive spending package for the first time since 2018. Now that Governor Cooper has signed SB 105 into law, we have finally given our state a budget they can truly be proud of and one that meets the most critical needs of North Carolinians.”

House Speaker Tim Moore

Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, said the following after Cooper’s signature:

“This budget continues the Republican-led legislature’s decade-long commitment to low taxes and responsible spending. The multibillion dollar surpluses these policies helped create are evidence that they’re working, and it means we can cut taxes even more.”

Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger

State Superintendent Catherine Truitt said in a statement that the budget funded many of the priorities for which she has been advocating:

“I appreciate the General Assembly’s efforts to craft a budget that puts us on a path towards much needed stability and allows for us to continue investing in our students, our education leaders, and our school districts.”

State Superintendent Catherine Truitt

Not everyone, however, was so optimistic. Public Schools First NC sent out an update to their email list about the budget, calling out the spending plan for not funding the Leandro comprehensive plan.

“It is disappointing that legislative leaders missed the opportunity to adequately support our schools and students, and instead prioritized tax cuts.”

Public Schools First NC

North Carolina Democratic Party Chair Bobbie Richardson praised legislative Democrats and Cooper for forcing Republicans to negotiate in a statement she sent out:

“While not a perfect budget, Governor Cooper and legislative Democrats forced Republicans to the negotiating table and delivered increased investments in teacher and state employee pay, infrastructure, and businesses as we emerge from the pandemic.”

North Carolina Democratic Party Chair Bobbie Richardson

She went on later in her statement to criticize Republicans.

“Republicans continue to obstruct critical investments like expanding access to health care and investing in our schools.”

North Carolina Democratic Party Chair Bobbie Richardson

North Carolina Association of Educators President Tamika Walker Kelly called the budget a missed opportunity in a video statement:

“After working for the past two years during a pandemic, no raises, and no state budget, educators have every reason to be disappointed. The state has the funds to provide bigger raises and to fully fund our constitutional mandate to provide a high-quality education for every single child in this state.”

North Carolina Association of Educators President Tamika Walker Kelly

See the full video below.