|

|

The halls of the General Assembly can seem far removed from the walls of a typical public school classroom in North Carolina, but somehow legislation that gets an upvote on Jones Street in Raleigh eventually trickles down to Junior’s school in Raeford. But how does it happen?

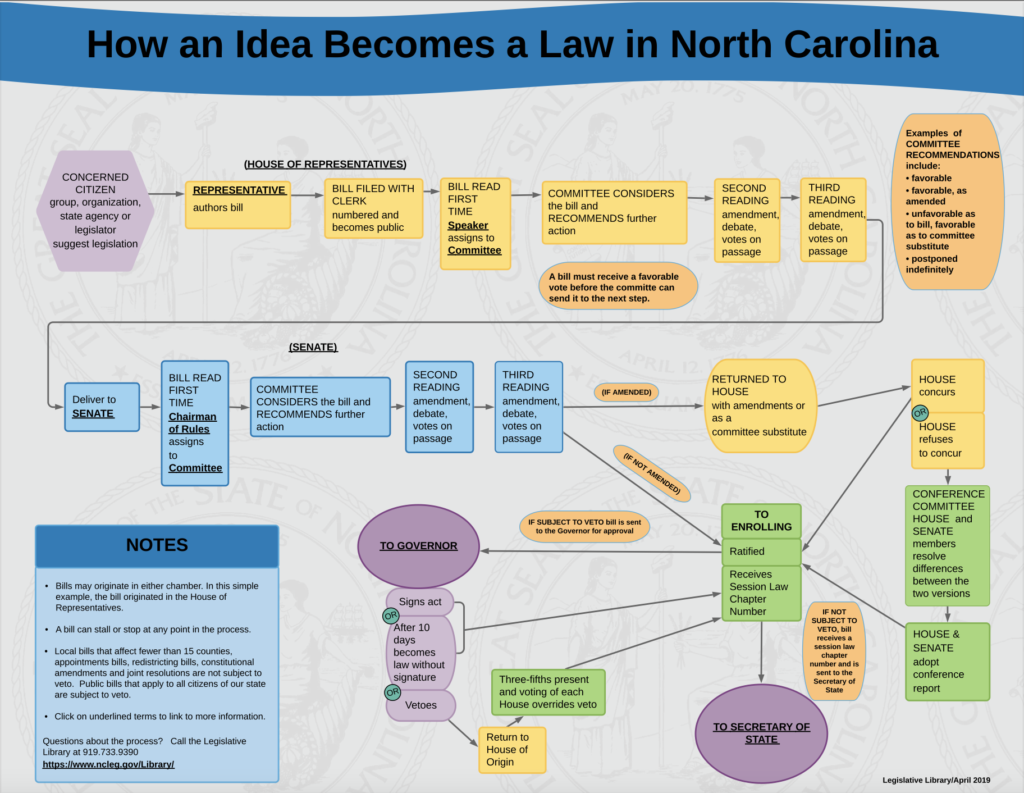

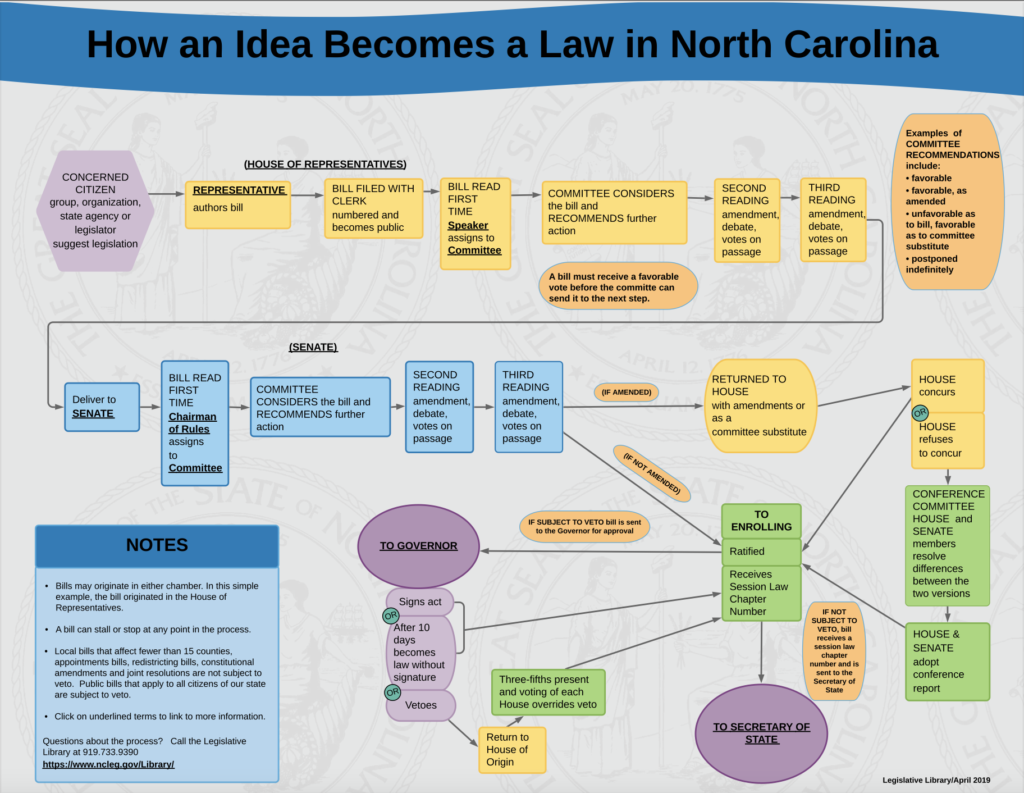

Well, if you’re just interested in how a bill becomes a law, then you can look at this section of the state General Assembly website and click on the section titled: How an idea becomes a law. That’s a relatively clear look at the journey of a bill from inception to enrollment. The legislature also has this somewhat-bananas chart to illustrate the process.

And if you want to know who the various education players are and where and how they get their power, then click here for an explanation.

But, if you want to actually follow the inception of a law from bill to the classroom, it’s going to take a bit more explaining.

An overview of a bill’s journey

Here is my own high-level breakdown specific to education bills. If you’ve ever wondered how a law journeys from lawmaker to the classroom, it happens like this.

A lawmaker or multiple lawmakers propose a bill. They file it. If leadership of the General Assembly decides it’s worthy, it will get referred to a committee. Since we’re talking about education, let’s say an education committee. If the bill gets a favorable vote in said committee, it may travel to a few other committees depending on what kind of bill it is and where it has been referred.

Once it has been heard in whatever committees to which it’s been assigned, it makes it to the floor of the chamber where it was initially introduced (either the House or the Senate). Once it passes that chamber, the whole process starts over in the other chamber.

If the bill makes it through all committees and the other chamber floor, it goes to the governor’s desk. If the second chamber makes any changes, it has to go back to the first chamber for a vote. If the changes are rejected, a conference committee gets together to hash out the differences, and then both chambers vote again.

With the exception of a few specific cases, a bill ultimately ends up on the desk of the governor, in this case Gov. Roy Cooper. The governor has a few options. He can sign a bill, veto it, or let a bill become law without signing it.

If he vetoes the bill, it then has to go back to the legislature where the chambers have a chance to override the veto. To do so, they need to have two-thirds of lawmakers in their respective chambers voting to override. A simple majority will not do. If they do override the veto, the bill becomes law. If not, it’s dead.

Ok, so if it’s an education bill, what happens next? Well, often it travels over to the State Board of Education. If there needs to be a new policy for school districts or schools to help the new law get implemented, the State Board may need to take action.

If the bill does need to go to the State Board, it will pass through State Board and/or Department of Public Instruction (DPI) staff, who will figure out what the State Board may need to do with regards to new policies. If a bill doesn’t need a new policy, staff will work with DPI leadership to figure out what needs to happen, including potential support or guidance.

Whether the bill goes through the State Board or just directly through DPI also depends on what the language in the bill says. Often, a bill related to education will lay out specific things that either the State Board, DPI, or both have to do. But it is rare that a bill related to education statewide doesn’t require some action or consideration from the Board.

DPI then makes sure the State Board’s policies are communicated and explained to the school districts. This can happen in a variety of ways: emails, phone calls, memos, technical support, and other kinds of webinars. DPI also has regional case managers who work directly with some districts, and DPI talks with the public information officers in local districts.

After communication from DPI, local boards of education may need to make local policies and decisions to decide how those policies get implemented in the school system. Then, it’s ultimately up to the district superintendent to make sure principals implement those policies in their schools and up to principals to make sure those policies become a reality in the classroom.

Now, that’s all very abstract, so let’s take a specific law and see how this works in reality. For the purposes of this piece, we are going to talk about legislation that was enacted fairly recently — legislation that mandates each district in the state must have a summer school program this year to help mitigate learning loss associated with COVID-19. Ready? Here we go.

How we get there from here

At a press conference on Feb. 16, House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, announced his plans for legislation that would require a summer learning program for schools in the state.

At that time, the legislation required each school district in the state to offer a six-week summer program to K-12 students with a priority for students who are considered at risk. The legislation said students who were not at risk could participate if space was available, and the legislation applied only to traditional public schools, not charter schools.

The bill offered no new funding but rather stated that it would be paid for “within funds available, including federal funds received by a local school administrative unit for the purpose of responding to the impacts of the coronavirus disease.”

Moore mentioned at the press conference that the legislature already appropriated $1.6 billion to be used to help schools reopen and that this money could also help with the summer program. That money came from the federal government to address COVID-19 impacts and mostly went directly to school districts.

In the House, the bill went through the House education K-12 committee, then the pensions committee (because of how hiring educators to teach in the program would affect their pensions), and then the House rules committee. On Feb. 24th, it passed the full House. The House made one major amendment during this time: Rather than being a six-week program, the bill was changed so that the summer program had to last at least 150 hours or 30 days.

The bill then went over to the Senate, where it was heard in the Senate education committee; the committee on pensions, retirement and aging; and the Senate rules committee. It passed the full Senate on April 1st and went to the governor.

While all this was going on, the General Assembly also passed a bill appropriating federal COVID-19 relief funding. A portion of that — $40 million — was set aside to help pay for the summer learning program. Read more about that bill here.

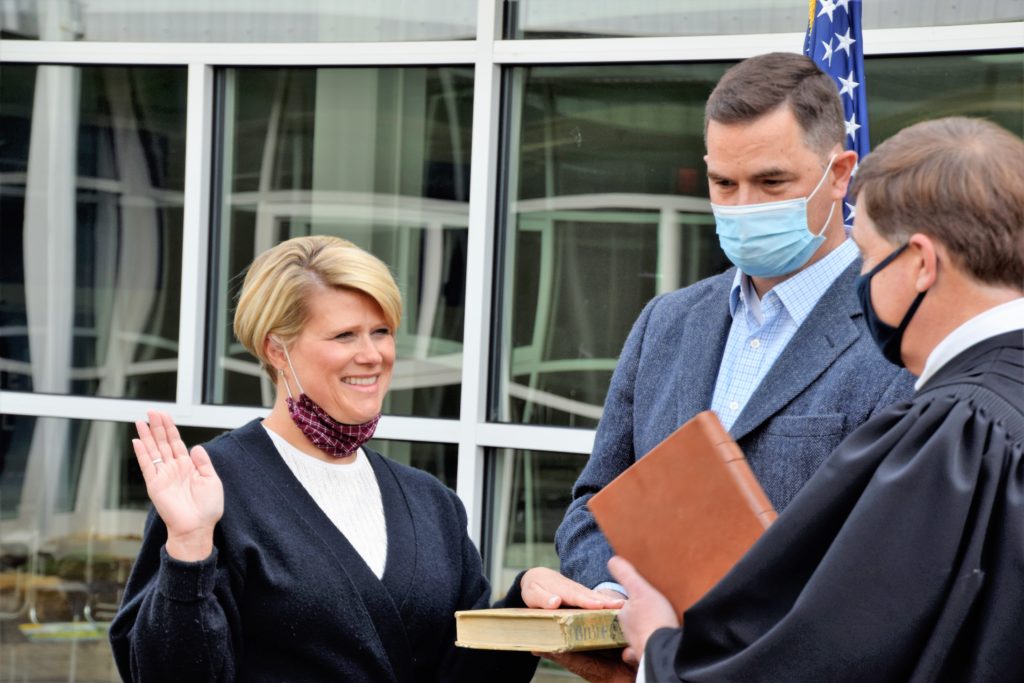

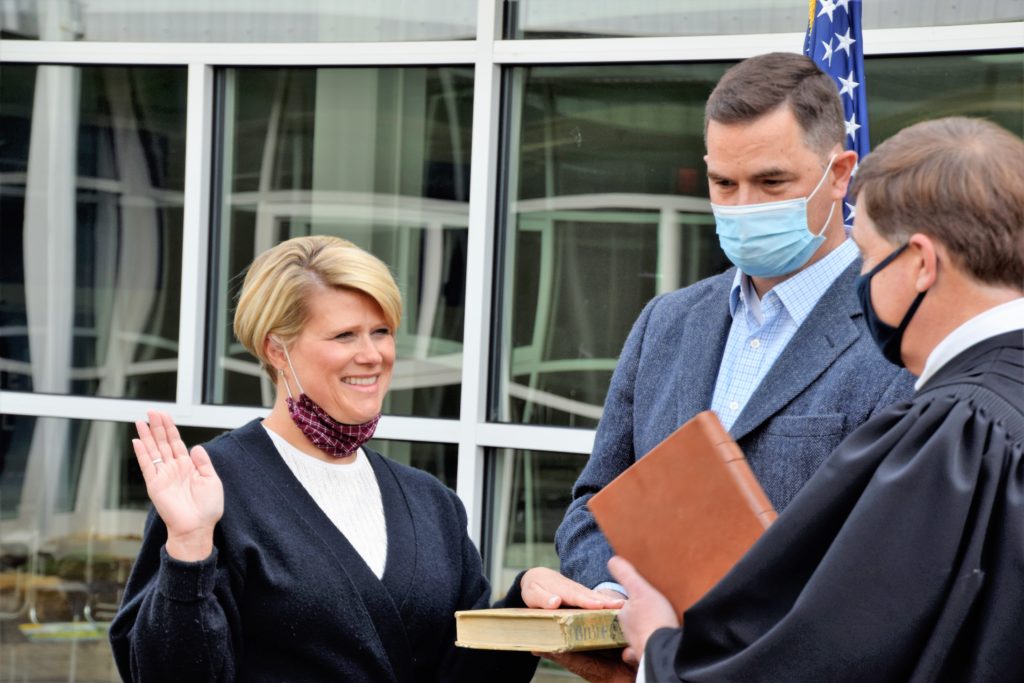

On Friday, April 9th, Cooper sent out an email announcing he had signed the bill.

The legislation went next to the State Board of Education, where staff from DPI prepared a presentation explaining the legislation and policy changes that the State Board needed to consider.

Part of the bill required the State Board of Education to come up with “innovative benchmark assessments in certain grades and core subject areas,” so that teachers could get a more regular look at how students are doing and address the learning loss they have experienced during COVID-19.

The State Board approved the following policy change as a result:

From there, the work of implementing the bill goes to DPI, local boards of education, and local superintendents. You see, the legislation requires each school district to come up with a summer learning program plan that has to be submitted to DPI by 30 days after the last instructional day of school this year. It’s up to local superintendents, local boards of education, and other district leaders to create that plan, though often DPI issues guidance on what such plans need to include. Districts send their plans to DPI, which has 21 days to tell them if any changes are needed.

After the plan is approved by DPI, the work takes place at the local level. Local boards of education may need to come up with their own policies or guidance to help their districts implement the program. Superintendents have to hire teachers to actually teach in the program, and then those teachers have to be prepared to take any student whose parents decide they should go to the summer learning program, which is entirely voluntary for families.

What started in the halls of the General Assembly and passed through many hands ends in the classroom of one teacher.

Under the program, students in grades K-3 will be offered instruction in reading and math. Third grade students will also be offered instruction in science. At least one “enrichment” activity will be offered at the discretion of the district. This could include things like sports, music, or art.

Students in grades 4-8 will be offered reading, math, and science, as well as one enrichment class. High school students will be offered instruction in end-of-course subjects and will be given modules and support for credit recovery.

The program will be completely voluntary for students. Kindergarten students who participate will be “exempt from retention for the 2021-22 school year.”

Even after the program, however, the work isn’t over. The legislation has reporting requirements for both local boards of education and the state DPI.

By Sept. 1, 2021, local boards of education have to report to DPI the results of their competency-based assessments for K-8 students at the beginning and end of the program, how many students went on to the next grade level after doing the program, how many students didn’t move up to the next grade, and the number of students who had to get credit recovery in high school.

By Jan. 15, 2022, DPI must report to the legislature a copy of the program plans for each district, “an explanation of the program outcomes,” and any other data that DPI thinks the legislature should know about.

And that’s it. That, ladies and gentlemen, is how a bill goes from the General Assembly to the classroom.