From Sparta to Brevard to Cullowhee, North Carolina is about 244 miles on a map. Sparta lies right off the Blue Ridge Parkway in the northwest part of the state, Brevard is southwest and sandwiched between state and national forests, and Cullowhee sits in the Appalachian Mountain range.

While they may seem similar because of their blue and green mountains of majesty, all places in the most western region of our state are not the same. They differ in size, economic struggles and successes, and especially in personal stories.

What are the stories of rural North Carolinians during the pandemic that has dictated 2020? We’ve heard of broadband issues, of the problems facing our rural hospitals, of an exacerbated housing crisis, and most of all, of the remote learning experience for students. The stories of rural North Carolina are deep and wide-ranging, just like the many unnamed peaks that paint a drive through the mountains.

In an effort to understand these different stories, we visited three rural churches who have taken on the task of operating a summer literacy camp amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The camps are funded by The Duke Endowment (TDE) and have the same goal, but took different paths in creating engaging curriculum and totally overhauled program formats to help children in their communities.

TDE started focusing on literacy efforts in the rural church in 2012. The mission was to combat learning loss or summer slide during the yearly summer break with a six week literacy camp. Rising first through fourth graders participate in the program, which works with school districts to identify students who need extra instruction. This summer’s schedule and student attendance may have been modified depending on the church, but the goals remain the same.

Recommended Articles

Why target these early learners? The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Double Jeopardy report states that “about 16 percent of children who are not reading proficiently by the end of third grade do not graduate from high school on time, a rate four times greater than that for proficient readers.”

Through TDE funding, churches are able to have paid staff for the camps. All those we visited this summer employ teachers. TDE also encourages churches to provide wrap-around services for students, whatever that may look like. Each camp provides breakfast, lunch, and snacks to students throughout the day. There are three hours of reading instruction and then three hours of enrichment. Each of those components looks different this year in light of the pandemic.

Since the program’s inception in 2012, 15 churches in 15 different counties have participated. There are 13 holding camps this year, either virtually or in person. How did they do it, and what changed from previous years?

We visited Brevard First United Methodist Church the week prior to the start of camp, Cullowhee United Methodist Church on their third day of instruction, and Sparta United Methodist Church during their last week of camp. The common thread? Dedication to doing what is best for students in their communities.

Brevard UMC: A literacy champion at the helm

This is Brevard UMC’s first year doing a summer literacy program, so it does not have a playbook from 2019 to compare. However, they have a 40-year education veteran in program director Fay Agar to help guide them down this reading road.

The list of Agar’s positions in education runs the gamut; from classroom teacher to reading specialist to principal. She has worked in elementary, middle, and high schools, as well as early colleges. Above all, it is easy to see her love lies in literacy.

“Reading is near and dear to my heart”

-Fay Agar, program director at Brevard First UMC

Agar ran a TDE-funded summer literacy camp in West Nash last year, so she is not new to the program. She and a committee from the church have detailed plans to adjust to the new health restrictions due to COVID-19. The camp runs from June 29 to August 7.

Summer camp break down

There is a 1 to 5 student-to-teacher ratio, as kids are divided into more rooms to keep group numbers low. The camp is focusing just on rising first and second graders this year, and students from both Pisgah Forest Elementary and Brevard Elementary are attending.

The camp is set up with specific drop off protocols, such as taking temperatures, asking parents at drop off if anyone has felt sick since their last meeting, and more. Brevard First UMC is offering transportation for those who need it, and volunteers from the church are driving buses.

Agar used community connections and state grants to receive additional funding and support for the new procedures of camp. She contacted a local carpet company and they cut carpet squares for each student to help with social distancing. She also received 500 cloth masks from the United Way.

Agar applied for and received a Dogwood Health Trust ION grant, a one-time grant they qualified for because this is the camp’s first year. With this grant, they were able to purchase computers for each student, headphones, all materials for individual packets, and more.

Computers are used for two assessments — a distinguished growth assessment and a weekly formative assessment. The teachers change their lesson plans weekly for each student based on the formative assessment. They also use the computers for everyday instruction. Agar points to Lyrics 2 Learn, a program that uses music to help with literacy, and Reading from A to Z, where students can download books with reading comprehension lessons.

“The same neural pathways that children use to learn to read, they use to learn music,” said Agar.

One of the guiding principles for TDE programs is family engagement, so the church planned on having a Parent Night every Thursday during camp. Agar directed us to a winding route that parents and student will take through the church building. The evenings may differ, but usually involve a greeting, a 10 minute session with teachers, and then picking up take-out dinner for the whole family.

Talking with Agar before camp started, she expressed hopefulness: “It won’t be easy, but I think we can rise to the challenge.” Her background in education has given her the tools and then some to lead this church through its first literacy camp.

“I explained to people (that) by doing this, we can change a child’s future and do great things for children and strengthen our communities as well,” said Agar,

Cullowhee UMC: Creative problem solving for in-person instruction

After a breakfast of individually packaged fruit, string cheese, a muffin, and more, the students at Cullowhee UMC are asked to zip up their bags and line up for a “zombie walk.” Getting to your classroom these days, while remaining six feet apart, can be very fun.

We visited Cullowhee UMC, which is located on Western Carolina University’s campus, during the third day of its five-week summer literacy camp. The Whee Read Summer Literacy Program has 17 students signed up to participate with five paid staff members, all of whom are educators, and an intern whose main job is to constantly sanitize.

Summer camp break down

When students arrive, there is a new structure to drop off similar to Brevard First UMC’s plan. Parents are asked to stay in the car, students walk up, have their temperature checked and logged, and then get a squirt of hand sanitizer before heading in the building for breakfast. Angie Lovedahl, elementary curriculum director at Jackson County Public Schools and staff member at this summer literacy camp, says they did their research before committing to having the camp in-person.

A child care facility in town has stayed open during the pandemic without incident, and they were in communication to learn from their process. She says, “We can still do a lot, you just have to problem solve. You just have to figure out a different way to approach it.”

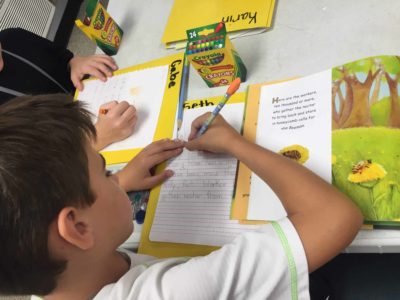

Students were seated at opposite ends of tables for meal time, and in classrooms, everyone was spread out and sitting on their own designated space. Teachers wore masks until they started reading to the class aloud or instructing for vowel sounds.

In the summer of 2019, they had around 85 volunteer reading buddies come in during the day to read with students. This experience needed to be eliminated this year. They also enjoyed a variety of field trips for the afternoon enrichment part of the program, which don’t fit in with this year’s safety procedures.

Enrichment activities have been more individualized and the team is thankful for the facilities on campus and the environment that surrounds the church. In deciding if they were going to hold camp virtually or in-person, Lovedahl says there were strong opinions. As long as they could do it safely, the educators believed it pertinent to have face-to-face instruction.

“The commitment was definitely there, that if we can do anything at all to avoid having to do more virtual or more remote learning, let’s do what we can. Let’s do whatever it takes (to have in-person instruction),” said Lovedahl.

Sparta UMC: Driving literacy home

Maggie Murphy and Kyla Gatton have become reading road warriors for the summer of 2020. Murhpy, the literacy director and fourth grade teacher at Pine Creek Elementary, and Gatton, Sparta UMC’s growth and community engagement coordinator, drive anywhere from 85 to 92 miles a week in the camp’s designated G.O.A.L mobile. What is a G.O.A.L mobile and why is it so important?

G.O.A.L stands for growth, openness, and achievement in literacy, and its importance lies within the drivers and what they carry. Sparta UMC’s literacy camp opted to go virtual this year, but instructors knew how important person to person contact was, especially for students who have been remote learning since March. With a combination of Zoom instruction and three weekly in-person touch points, Sparta UMC continues to build trust with the community.

Summer camp break down

The G.O.A.L Summer Literacy Camp Zoom call starts at 9:30 a.m., Monday through Friday. They begin together, singing songs or playing a game. Eighteen students are engaged in some capacity, and the program acknowledges the challenges parents face in the remote learning world.

At 9:40 a.m., Murphy, who is also the 2020 Burroughs Wellcome Fund Northwest Region Teacher of the Year, “swooshes” the students into their breakout rooms where they have instruction for the morning.

We joined some breakout sessions where teachers were using programs like Learning A to Z and Hue. Students were reading out loud, holding up banana cut outs or playing “scavenger hunt,” a virtual show and tell. Later in the morning, educators also have one-on-one time with each student for individual instruction based on the child’s growth.

After morning instruction on Mondays and Thursdays, students know to expect the G.O.A.L mobile. This is a huge part of camp, and two of the three in-person touch points Murphy and Gatton know to be imperative to the program.

On those two days, they load up a car with backpacks, books, snacks, enrichment activities, and fun treats for the students of camp. They are also able to deliver materials from teachers so instruction can keep progressing. Students earn points for attendance, respectfulness, reaching goals, and more. Based on the points, they get to pick out special prizes straight from the G.O.A.L mobile. Gatton and Murphy also take this time to check in with parents and see how everyone is feeling.

Donning masks, Gatton and Murphy knock on doors, get students to put on gloves, and then they get to go searching for just the right treat. Gatton and Murphy pick out books based on the interest of each student and they get to take as many as they want.

The other weekly touch point is on Wednesday nights when the church’s Grace Kitchen opens for a community dinner. During the pandemic, the dinner is take-out only, but they can feed anywhere from 150 to 200 people. Families of the literacy camp students are encouraged to stop by for dinner and pick up materials for camp. All the teachers are there to enthusiastically greet students and help with getting food to cars.

What was the deciding factor in making this year’s camp virtual? Leaning on the first rule of the founder of the Methodist Church, John Wesley: Do no harm. Gatton explains, “We just kept coming back to the fact that we work so hard in our communities to establish ourselves as a trustworthy place, as a safe place.”

“You know, our heart as educators, as the church, is we want to impact these kids in the biggest ways that we can, and we know that in-person is going to have the greatest effectiveness on that, but at the same time, our heart is also to keep our kids safe.”

– Kyla Gatton, Sparta UMC’s growth and community engagement coordinator

The G.O.A.L mobile delivers that message and more as Sparta UMC works in many ways to support students and their community.

Editor’s note: The Duke Endowment supports the work of EducationNC.

Recommended reading