Four women from Mt. Carmel Baptist Church stand behind a make-shift breakfast buffet in the Bryson City United Methodist Church building, serving children sausage biscuits at 8:30 a.m. The room is out of this world — literally — decorated as a space ship with windows to view the greater galaxy, planets, stars, and the occasional cartoon alien. Rising first, second, and third grade students trickle in, taking a plate of food or plopping down beside friends. This is the second week of Swain County’s Congregations for Children (C4C) literacy camp, and the kids know the drill.

Different from other C4C programs EdNC.org has previously reported on, this camp is supported by seven congregations in the county, only one of them identifying as Methodist. C4C is by definition a state-wide initiative of the United Methodist Church focused on supporting children in public schools. Of the four focus areas listed on the Western North Carolina Conference’s website, K-3 literacy is “at the heart of the ministry.”

In Swain County, there is an inter-denominational C4C council of eight people, comprised of church members and school system representatives. They provide support to schools throughout the year by distributing books to kindergarten through fifth grade students, adopting classrooms to help with supplies and maker spaces, providing food during the holiday break, and more.

Katrina Turbyfill, currently director of school improvement in Swain County Schools and formerly the data and literacy coach, helped create the curriculum for the summer literacy camp. She said for this program, they targeted certain students who qualified for Reach to Achieve, who they also believed would benefit from a two-week literacy camp right before school began. In total, they had 36 children attend from Aug. 5 to 8 and Aug. 12 to 15.

What does a day at literacy camp look like?

After breakfast, students gathered around the spaceship set and read a book about the solar system. Wayne Dickert, pastor at Bryson City UMC, narrated, and then the group stood up for some dancing and singing.

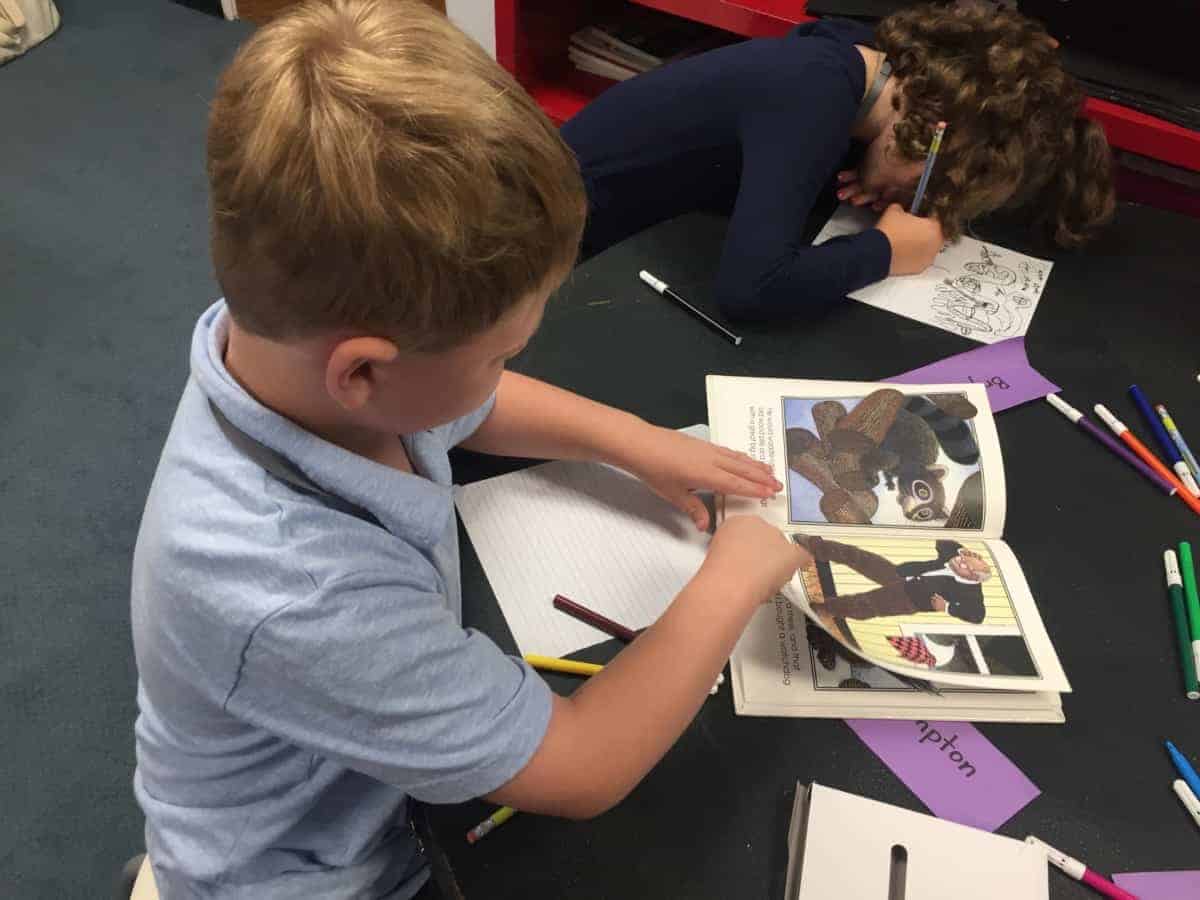

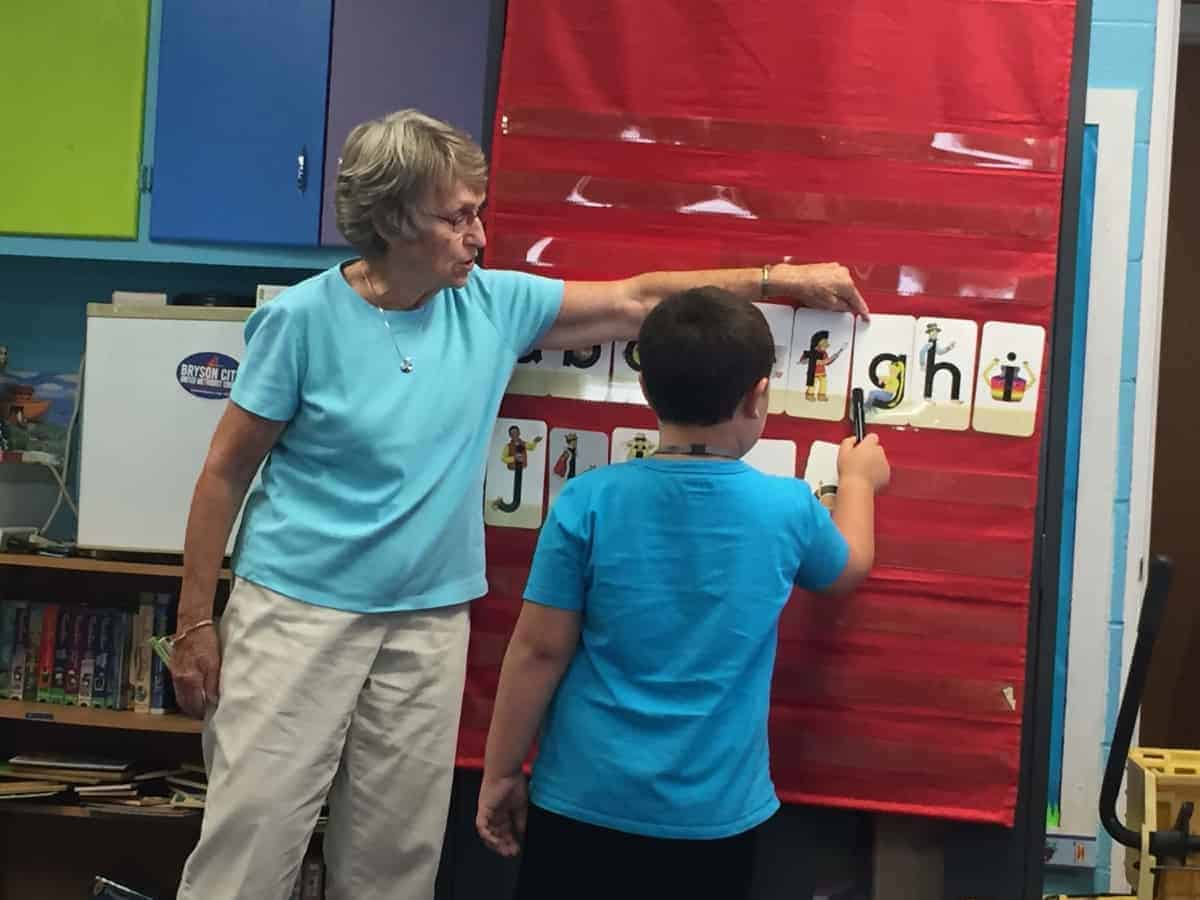

Children were then divided into grade levels and went to their respective rooms inside the church. Each group dove right into literacy work. Retired educators (on the day I visited, a reading recovery teacher, an elementary school teacher, and a principal) oversaw the classrooms, addressing the five components of literacy: fluency, phonological awareness, phonics, comprehension, and vocabulary with the day’s lesson.

That lasted for a little less than two hours with small breaks. Students also practiced their reading theater, which they performed on the last day of camp to family members.

After a morning of reading, students received a free lunch and then participated in a number of activities offered throughout the two weeks. Again, volunteers from the community came to support the camp with their time and skills. Students were offered activities in art, music, crafts, games, drama, and STEM.

Ralph Murphy, music director at Bryson City UMC and a retired psychologist for Cherokee Central Schools, played the guitar and sang. After a number of tunes, he put his instrument down and made balloon animals for everyone.

Sandy Putnam, a retired biologist, came and taught a science lesson about the ocean, with all the things early learners would want to see and touch. Students were able to take home a bag of seashells after the activity. As a gift to the camp, Putnam purchased a science book for each student to have as their own on the last day. In addition to the science books, at the completion of camp, students take home a backpack full of donated books, a special shirt, and a summer literacy camp certificate.

Students participating in the summer literacy camp closely reflect the demographics of the school district’s overall student population, with 21.7% of the summer literacy camp students being members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, 9% identifying as Hispanic, and 69.3% identifying as white.

Parents were given a post-camp survey to see if the students’ attitudes of reading had changed. Questions were posted like: “How much has your child’s reading fluency (ability to read without hesitating/stopping) increased?” or “What, if any, changes to this camp would you make?” This is the first year of the summer literacy camp, and the organizers are hoping to learn from this year’s experience to grow for the next.