In 2012, The Duke Endowment partnered with one rural church to test a program to combat summer learning loss.

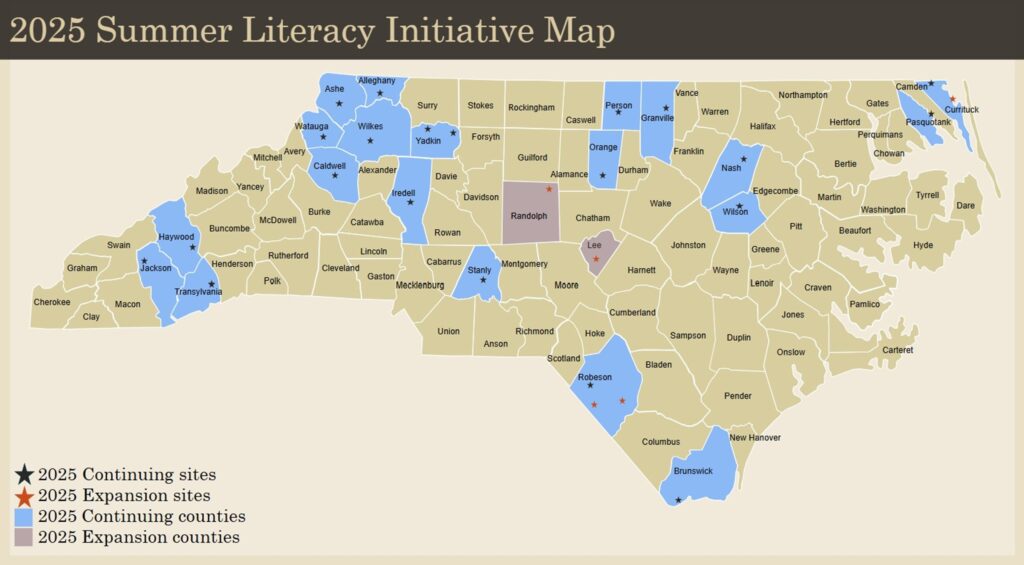

Thirteen years later, the initiative that has grown from that investment includes several funders who work together with statewide nonprofit supporters and local partners to provide evidence-informed summer reading camps for rising first through rising third graders in more than two dozen rural North Carolina communities.

It’s called the Summer Literacy Initiative.

As the initiative has expanded across the state, North Carolina has embarked on its own science of reading journey. In April 2021, the N.C. General Assembly passed the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021 with bipartisan support. Since then, more than 44,000 K-5 educators have successfully completed LETRS training, and there are now early literacy specialists in every county. But the impact of COVID on learning loss lingers for students, and summer reading programs like the initiative are arguably more important than ever as the state strives for gains in reading outcomes.

EdNC’s reporting on the science of reading

During the school year, students have access to a steady flow of literacy resources in school. That flow continues during the summer for many middle- and higher-income students. But for children who live in high poverty or rural areas, the flow can slow to a trickle. Consequences can be cumulative and long lasting – and the gap is harder to close once it opens.

That gap is commonly referred to as “summer slide.”

“We see children make great gains at the end of the school year,” says Allison Weaver, a literacy interventionist during the school year and director of one of the initiative’s summer reading camps. “But those gains can be so fragile.”

The Summer Literacy Initiative has been an experiment in how to identify and scale a best practice built on research and customized to different communities, with local collaborators together addressing a specific social issue — in this case, summer learning loss.

A three-pronged approach has guided the initiative since 2012, when it was just an idea:

- Recruit students who need literacy intervention for a reading camp housed within a rural congregation, leveraging its role as a convener and anchor institution in the community;

- Partner with local elementary schools to provide evidence-informed and data-driven instruction by highly qualified teachers; and

- Engage parents/caregivers in the education process through weekly gatherings.

Since 2013, the program has grown from one site to 26.

Nearly 2,500 students have been served to date, with at least 650 more enrolled this summer. The need is only increasing.

“Often, the Summer Literacy Initiative at our church is the only opportunity in Transylvania County to improve reading skills, preventing the ‘summer slide’ and helping kids reach grade level reading proficiency. In fact, we received over 300 applications for our program this summer for only 30 places,” said Veranita Alvord, lead pastor of Brevard First United Methodist Church.

To ensure the camps are being administered across the state with fidelity to the approach, each site agrees to:

- Run camps in their congregational facilities for four to six weeks in the summer, Monday-Friday, with full-day programming for early elementary students who need reading intervention;

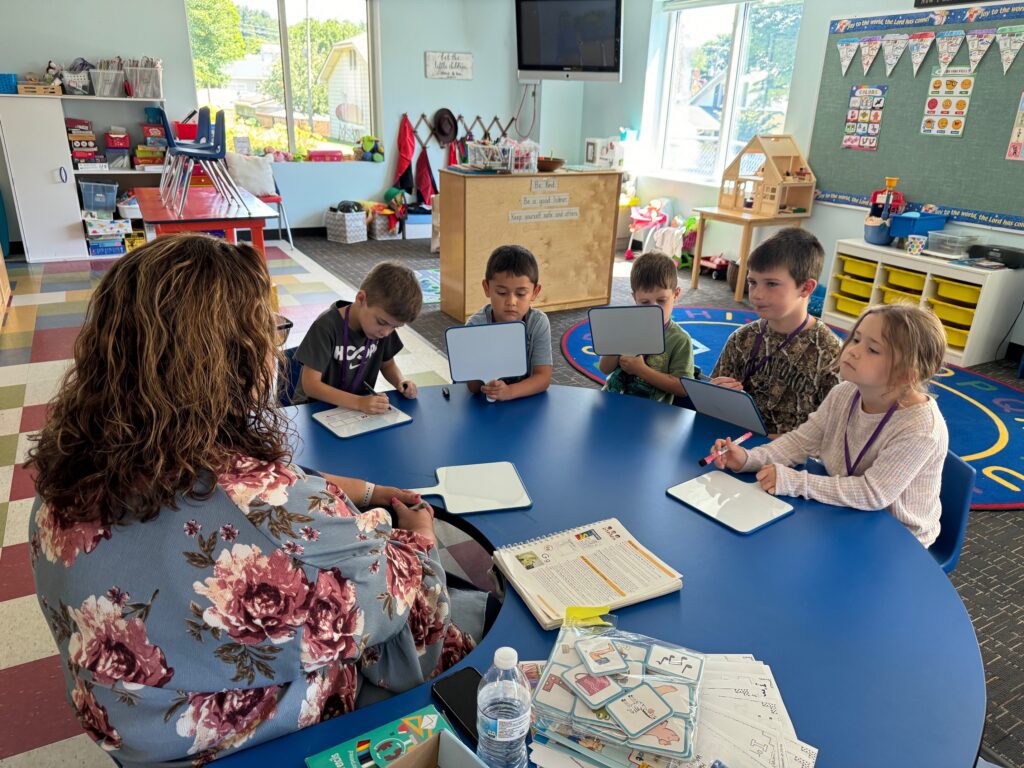

- Hire and equip excellent certified public school teachers who provide 80-90 total hours of morning reading instruction in small classes of 10-12 students;

- Engage volunteers and others from the congregations and other community organizations to:

- Offer afternoon enrichment activities each day;

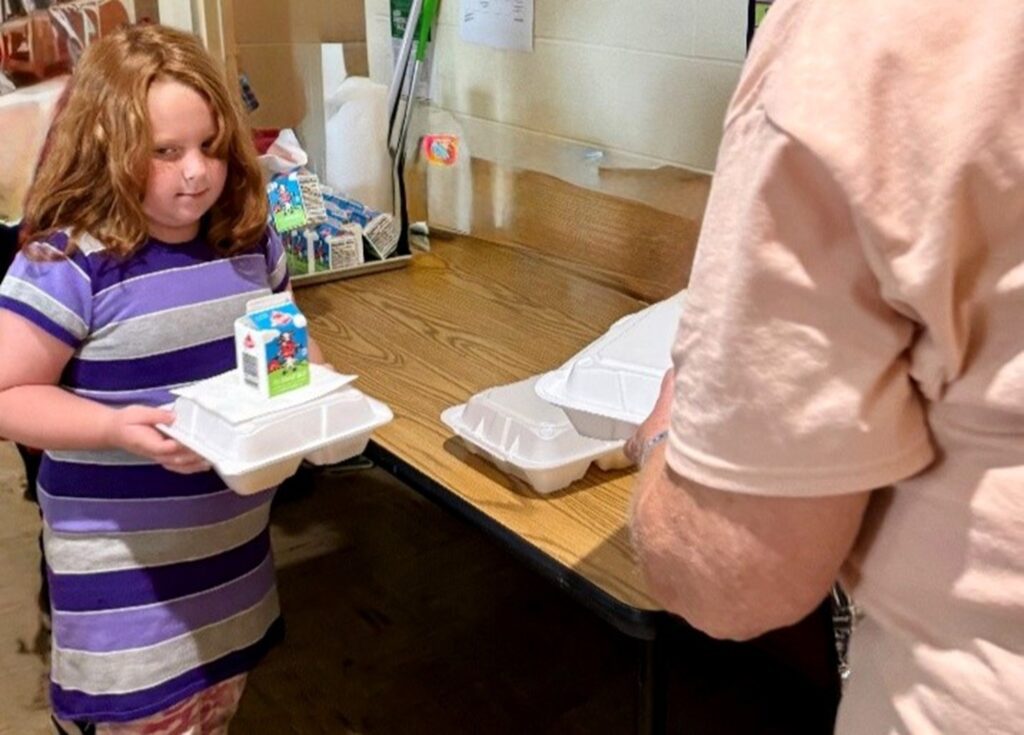

- Serve a healthy breakfast and lunch to all students; and

- Wrap students in love and overcome barriers to their participation and learning;

- Engage parents/caregivers through weekly workshops and other activities; and

- Contribute to the ongoing development of the program model through data collection, research activities, and participation in the statewide learning community facilitated by the Endowment.

The model is aligned with the state and legislature’s commitment to the science of reading.

After seeing a promising model emerge from the first sites, in 2016, the Endowment consulted with Dr. Helen Chen with the Harvard Graduate School of Education. With Chen’s guidance, the Endowment and the two participating sites identified six principles that continue to guide the Summer Literacy Initiative:

Chen now provides program development support for the Endowment, while The Impact Center at the UNC Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute provides implementation support for sites and the American Institutes for Research (AIR) is gathering evidence for the initiative.

For the 2024 sites, AIR found:

- Students showed statistically significant growth in reading skills again, as they have in all previous years of the program;

- Rising first graders demonstrated the most gain;

- On average, students gained about three months of learning;

- Gains were similar by race, ethnicity, and gender;

- Students enjoyed reading more after the program and had higher reading self-confidence; and

- Students agreed that teachers and grownups believe in them.

Those positive changes are among the primary reasons that faith communities are eager to deliver the programs faithfully. They know that these outcomes are associated with lasting improvements in achievement for children.

“Last summer, the Summer Literacy site at Brevard First United Methodist showed that our students increased their reading proficiency by four months in six weeks. This level of improvement is almost unheard of related to literacy gains over the summer,” said Alvord. “Most importantly, to us, the people of Brevard First United Methodist Church, literacy gives kids the self-esteem they need… and equips kids to face the future unafraid.”

What has the Endowment learned?

Replicating and scaling best practices includes reflection and iteration over time.

As evidence of the initiative’s effectiveness accumulated, the Endowment and its United Methodist rural church partners have cautiously expanded and evaluated what was working, while adapting the model with each learning.

In the early years of the initiative, recruiting churches was more challenging than expected because of a “lack of capacity” cited by the congregations. In response, the Endowment now provides technical assistance and has established a learning community to support the churches.

Through a grant to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Impact Center at FPG has built a system of implementation support and workforce development that enables faith community sites to faithfully deliver the program in their communities. Additionally, the support structure sets the initiative up for more rapid expansion in the future.

Other important lessons learned over the years include:

Guiding principles alone are not enough to ground and define the program; shared values must also be identified. In 2019, after research and conversation, the Endowment and its summer literacy network partners (12 churches at the time) adopted the cultural humility framework and trauma-informed approaches as the initiative’s core values.

Strong partnerships with school districts and local elementary schools are critical, so faith communities are encouraged to establish open lines of communication with their school district leaders and to create a true local public-private partnership that forms the heart of the effort.

To make sure the camps are ready to hit the ground running when they open in the summer, the initiative is a year-round commitment for both funders and grantees, with multiple targets and deliverables throughout the calendar year, so the Endowment and its partners now support year-round learning, planning, and capacity building.

For programs to become a long-term offering in rural areas, the entire local community must buy in, financially and in other ways. Grant funds can be unreliable and hard to acquire, so the Endowment and its partners are providing support to congregations and their community collaborators for long-range financial planning.

The need for programs like these in rural communities is vast, and limiting the model to The Duke Endowment and rural United Methodist churches is not sufficient.

“We’d love to be able to see rural faith communities all across North Carolina implement these programs,” Chen says. “We think any congregation with the desire and heart to do this can really impact their community and serve their most vulnerable in this way.”

In response to these learnings, the Endowment convened other like-minded funders to explore opportunities to reach more students in more communities and awarded funds to the NC Rural Center to expand the initiative.

What’s next?

The NC Rural Center, the two United Methodist conferences in North Carolina, and funders are actively recruiting and screening faith communities who could deliver programs in their facilities as early as summer 2026.

AIR is conducting a study that will compare the reading outcomes of summer literacy students to a group of “matched” students who did not participate in the program.

Current funders — which include Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, Barnhill Family Foundation, Camber Foundation, Anonymous Trust, and ChildTrust Foundation, along with The Duke Endowment and the Mebane Foundation — and prospective funding partners are meeting to strategize for expansion to the communities who need it most.

Seeing first-hand the long term benefits to students, families, congregations, and communities, local leaders refer to the experience as “the magic sauce,” and so the network is focused on the future, heeding the call to reach more students.

Those who are interested in exploring opportunities to join the expansion effort can download this fact sheet. If you have any questions or need additional details, please feel free to reach out to Courtney Ingram, the Summer Literacy Initiative liaison at the NC Rural Center.

EdNC’s reporting on the Summer Literacy Initiative

Highlights from camps across North Carolina

EdNC visited several camps last summer, from West Jefferson in Ashe County in western North Carolina to Moyock in Currituck County in eastern North Carolina. The Duke Endowment has already been on the road this summer. Take a look.

West Jefferson United Methodist Church in Ashe County: Involving the community in literacy

by Mebane Rash

“It just meets such a community need,” says Allison Weaver, the director of the Summer Reading Adventure and an educator with more than 30 years of experience.

“To make a program like this work, you have to have a very dedicated, energetic church that is willing to go the extra mile and see the big picture,” Weaver said.

“We just want to help,” says Pam Cope, the head of the church committee. “God introduced us to The Duke Endowment by accident.”

Cope heard about the initiative when she attended a conference hosted by the Western Conference of the United Methodist Church. It was the answer to her prayers on how to improve literacy in the county.

“We love this program,” she says.

The local Chamber of Commerce helps spread the word.

“We get lots of support from the school district,” says Weaver, including a cart of Chromebooks for assessments and access to resources for literacy instruction.

Different leaders from the community, including ministers from other churches, meet daily with the students in a morning circle to talk about character building.

The students have access to summer enrichment programs through the local public library and other community partners.

Local interpreters have helped with translation for families where English is a second language.

Another church donated a church van for the summer to assist with transportation. There are two to three riders in the morning, and six in the afternoon — some of whom are dropped off at other child care facilities. Other churches have donated money for snacks and other costs.

The Rotary Club contributed money for books to be sent home weekly with the students, encouraging them to build their own library. The church will send home bean bags for each student to build their own reading nook, and a church member also made a quilt for each student.

Shoes for Kids will give each student a new pair of shoes, and the church blesses the backpacks of students ahead of the start of the school year.

You can see local media coverage of this camp here and here.

United We Read! in Yadkin County: The power of partnerships to change lives

by Kristen Richardson-Frick

For the first time this year, The Duke Endowment is not the primary funder of all of the initiative’s local programs. For the two sites in Yadkin County, the Mebane Foundation, with its focus on providing early literacy interventions for students in their geographic priority areas, is supporting at least half of the costs in 2025.

United We Read!, the umbrella name for the Boonville and East Bend summer literacy camps, has demonstrated the effectiveness of partnerships to uplift students, families, congregations, and individual volunteers since its inception in 2019, when seven local churches known as “East Bend United” together committed to the statewide initiative. That year, their program served 19 students.

Led by lay volunteers and supported by pastors, East Bend United activates a broad network of community organizations that have grown the program from one site to two, 19 students to 72, and four feeder schools to eight. In so doing, they have more than doubled their ability to serve the students most in need in the county, as well as the number opportunities for community members to make a difference in children’s lives.

On the day of the Mebane Foundation and Duke Endowment site visit, a community volunteer was preparing to teach an enrichment science lesson involving dyeing roses different colors. High school and college students at both sites were serving as “reading buddies” on couches in a youth Sunday School classroom. Church volunteers served SUN program meals provided by partner public schools to students and rode with YVEDDI drivers in Community Action Agency vehicles to accompany the children to and from camp.

The smell of chicken tacos in crock pots wafted through the fellowship hall, promising a family engagement dinner for students, caregivers, and siblings free of charge by a neighboring church that evening. Ashley Miller, site director for the Boonville camp, spoke of having taken the entire camp the previous day to the dance studio across the street for a weekly afternoon enrichment dance lesson, where the owner — a church member — is teaching the students for no fee.

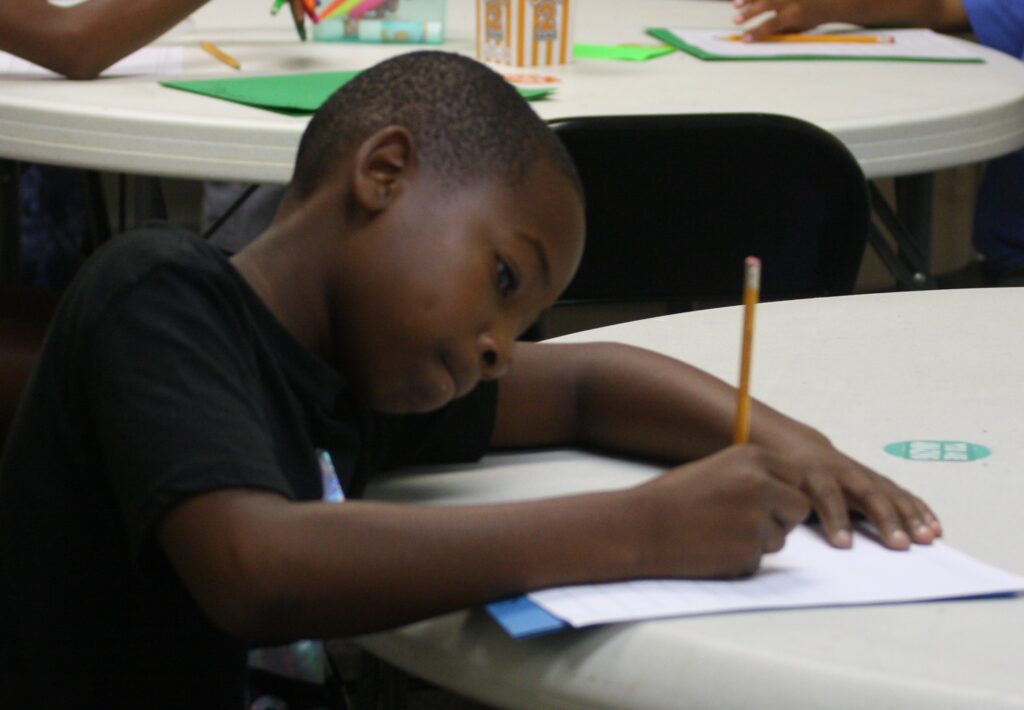

The children got comfortable for their literacy lessons using their personal pillow pouches, handmade, and prayed over by the congregations’ quilting ministry. They learned with headphones, devices, and curricula loaned by the public schools at which the lead and assistant teachers work during the school year.

Local, regional, and statewide partnerships sustain every aspect of the two sites’ efforts, and the results are attracting attention and interest.

“I don’t just have a waitlist for students who want to attend the program,” Miller said. “I also have a waitlist of teachers who want to teach here.”

Teachers across the statewide network cite small class size, the freedom to meet children where they are and to use the skills they’ve been taught through LETRS training and other science of reading-aligned professional development opportunities, and a different environment — a faith community space — as reasons they want to work in the program, and return year after year.

They see the difference that the model’s unique approach makes.

“We have one little girl in the program whose brother was here for the last two years. But he didn’t qualify to come this year because he reads on grade level now. He was sad, but we were thrilled we did our job,” Miller said.

“We have lots of stories like that,” added Jamie Sloan, site director in East Bend, with a smile.

First United Methodist Church in Elizabeth City in Pasquotank County: Why including local teachers and building a program that works for students is important

by Hannah Vinueza McClellan and Kristen Richardson-Frick

At First United Methodist Church in Elizabeth City, all the lead teachers for the summer camp have worked in the local school system, and the church aims to hire teachers who reflect the student body of the system and camp.

“We try to hire a staff that represents the communities the students live in every day and to pull teachers from the same schools that our students attend. We want our students to feel comfortable and well-represented. Our best quality as a program is that we start with the student and build a program that gives them every advantage,” site director Andrea Rosewall, herself a local teacher, said.

“The students come in on the first day and are like, ‘Oh, that’s Ms. Moore! I know Ms. Moore!’ There is a comfort level there. They get to build on their previous relationships with their school teachers here, and to see that the teachers are on their side. These teachers are committed to helping these students learn,” Pastor Jim Jones added.

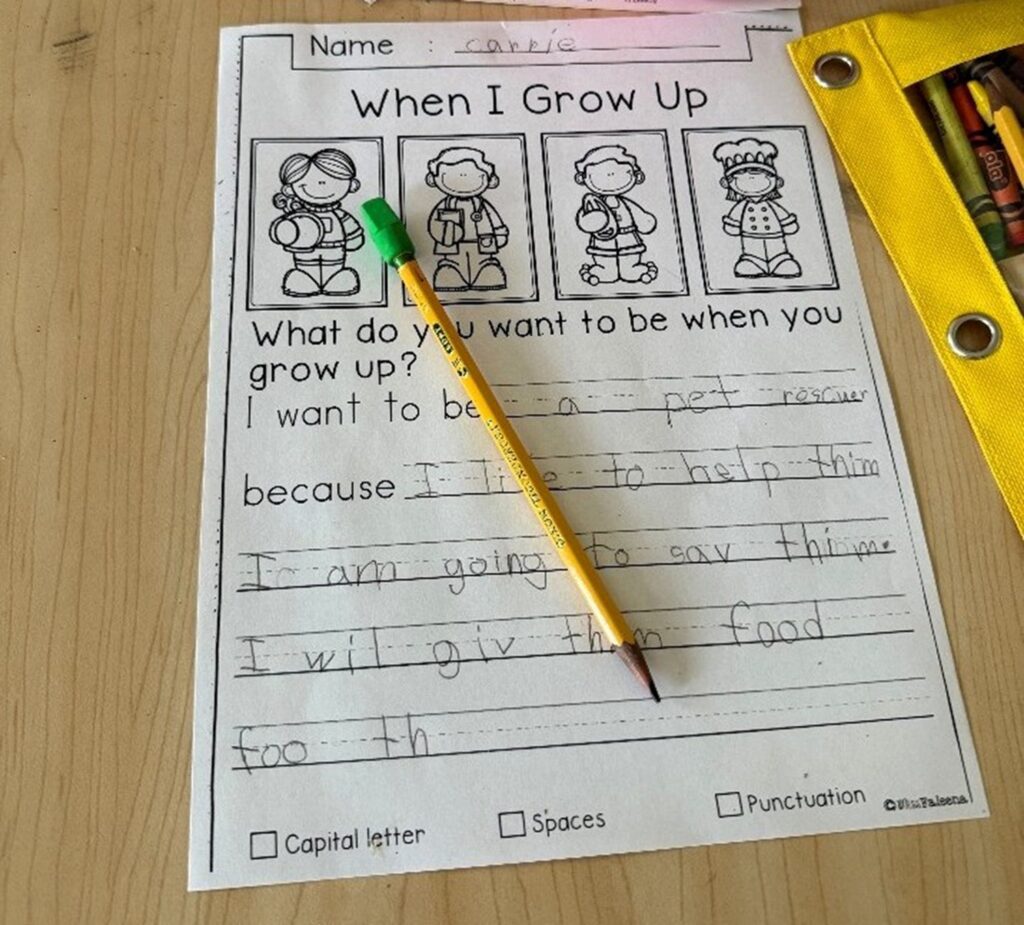

Parents report that their children are reading more, they are more interested in reading, and that’s happening even with students that have found reading difficult in the past.

Church leaders highlight how a summer program provides a space for kids to grow as learners, noting the opportunity to “watch them open up during the program.”

Currituck Church Cooperative: Serving with vision, focus, and hope

by Hannah Vinueza McClellan and Kristen Richardson-Frick

2024 was the first year of camp in Currituck County, where Moyock United Methodist Church accepted the challenge to build a program with just a few months of preparation. They began small, with one classroom enrolling 12 students.

Tess Marler became the lead teacher and site director for the program. During the school year, she serves as an interventionist at Griggs Elementary School in Currituck County Schools. Marler says because she has seen the science of reading pay off for students, she was eager to offer a way to continue that payoff for kids who needed a boost during the summer break.

Marler says the students are growing a lot as readers in the program.

“We worked really hard to get it all together,” she said during the last week of camp in 2024. “It’s been going fantastically.”

Building on that momentum and effort, Marler and three local pastors worked together to expand the program for 2025, to serve three times the number of students at two church sites. The “Currituck Church Cooperative SLI Camp” now runs concurrently in Moyock and at Pilmoor Memorial United Methodist Church in Currituck, sharing Marler as site director and volunteers from several churches and community organizations, including the local senior center.

“Reading buddies” come in every morning to read with students. On the day the Endowment visited Pilmoor Memorial, so many volunteer buddies had shown up that every student had their own.

Josh Tester is the pastor at the Currituck church, where the first year of camp has brought renewed energy to the congregation.

“VBS (Vacation Bible School) is great, but this is real cool,” he said. “This year, our congregation poured all our effort into reading camp and didn’t have VBS here. Every week at worship, someone who is helping out stands up and encourages the rest of the church to come to family engagement night or camp during the day.”

“This is real. This is good and meaningful.

— Congregation member, Moyock United Methodist Church

You need to experience it.”

Editor’s Note: The Duke Endowment supports the work of EdNC.

Recommended reading