|

|

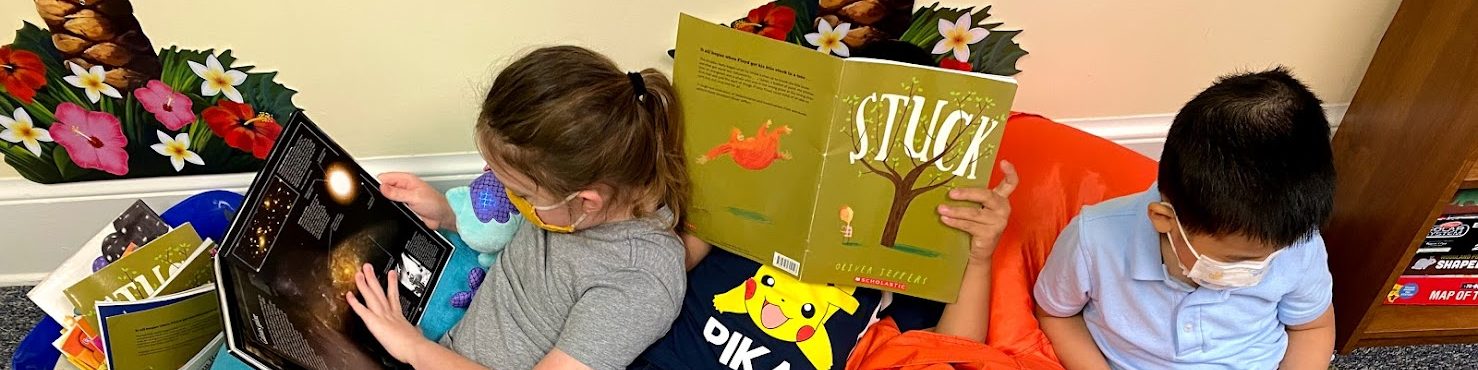

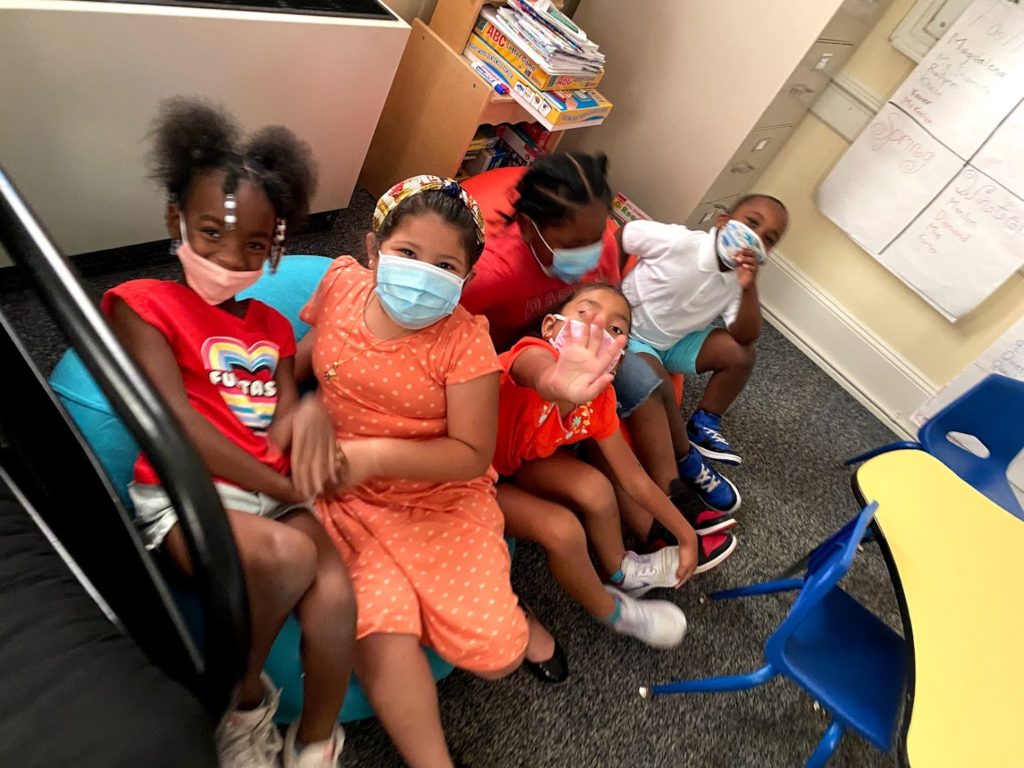

Shamira Moore kicked out one leg while swinging her arms in the air and sounding out the letter “K.” Six rising first graders followed suit; listening, mimicking, and giggling as they sounded out the alphabet with their teacher at First United Methodist Church’s summer literacy camp in Elizabeth City.

During the school year, Moore is a kindergarten lead teacher at Sheep-Harney Elementary. This summer, she is working with her students on sight words, building written expression skills, and reading. A few of the kids attending the literacy camp are her former students.

Moore grew up in Elizabeth City, attended Elizabeth City State University, and now works in the place she has always called home. This past school year was her second year of teaching, and she said the most difficult part was meeting the needs of all her 19 students, some who were learning in person and some who were learning remotely. In addition to her normal workload, she called parents frequently, sent out a daily email update on what they learned in class, and drove work packets to students on the weekends.

Even though this year was difficult, she believes this is the only profession for her.

“This is my hometown, and I just wanted to touch lives here, the little ones in Elizabeth City. And I love kindergarten.

Shamira Moore, kindergarten teacher at Sheep-Harney Elementary

I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

How did some of these students come to be back in the same room with their teacher over the summer months? Through The Duke Endowment’s eight-year-old summer literacy camp initiative.

The beginnings of a summer literacy initiative

The United Methodist Church has over 1,900 churches in North Carolina. The Duke Endowment (TDE) estimates around 70% of those are in places they consider rural. These buildings are used for worship but also can be anchors of communities in other ways. We have seen them be hubs for food distribution, sources of supplies for the first day of school, locations for blood drives, a place for students to connect to Wi-Fi, and much more.

Chantalle Carles was a Duke Endowment fellow from 2011 to 2013 and had previously been a Teach for America corps member. Through her experience as an educator in Henderson, she believed churches could play a role in the achievement gap and help struggling students over the summer. Her fellowship with TDE culminated in a capstone project where she developed the case and plan for a six-week literacy camp housed in a rural church.

In the summer of 2013, Monticello United Methodist Church in Iredell County held the first literacy camp. The next year, they added a church in Brunswick County. In 2016, TDE started evaluating the programs for evidence-based impact to see if they could replicate the initiative with more churches.

Fast forward to the summer of 2021, and 17 churches that span from Jackson County in the west to Pasquotank County in the east are running summer literacy camps. By August 2021, more than 982 students will have been served by the initiative. How do these summer literacy camps operate, and how is The Duke Endowment involved?

Literacy camp mechanics

The Duke Endowment literacy camps span six weeks and require 90 hours of literacy instruction. School districts recommend students to attend the camps, and TDE recommends weekly assessments to encourage data-informed and student-focused instruction.

After the required three hours of morning literacy instruction, students eat lunch and participate in various enrichment activities in the afternoon. These include trips to the planetarium or library, swim lessons, or a stop at an ice cream shop. At Red Oak United Methodist Church, a fire fighter came to the camp and taught the students how to use a fire extinguisher as part of their enrichment activities.

TDE funds the literacy camps by giving grants to churches. These grants work on a sliding scale. Each church provides a sample budget, and depending on students in the program and local community support, the grant amount fluctuates.

The biggest line item is paying staff, and churches offer competitive pay based on teacher salaries in the area. One of the six guiding principles in the program is hiring empowered and effective teachers. The other are: have an already thriving and engaged church community; have a strong community investment; offer wrap-around services; create family engagement; and use data-informed, student-focused instruction.

COVID-19 forced TDE to remain flexible around its literacy camp requirements. In the summer of 2020, some camps went online, some stayed in person, and some churches opted to not hold one at all. This year, knowing educators worked harder than ever, TDE allowed changes to the schedule. Some camps are taking Fridays off and some are shortening the duration of the camp from six to four weeks.

Kristen Richardson-Frick, associate director of the Rural Church program at TDE, says they are always trying to collaborate with the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI). In 2019, DPI worked with them on recruitment and assessment, and then COVID-19 hit. With a statewide mandate that schools offer summer school this year, some students who would attend a TDE literacy camp are getting instruction from their district instead.

Regardless of these changes this year, it is clear to see students and staff are still moving together towards the goal of reading readiness, and that the churches are happy to hold space for the work.

“We’re looking for places where we can plug into our community more,” said Benny Oakes, pastor at First United Methodist Church in Elizabeth City. He said programs like this are good examples of that work.

Richardson-Frick believes this model can be replicated across the state and that it makes a large difference in students’ lives as well as the lives of their families.

“It [is] just a new kind of really impactful community partnership and engagement” she said, that has the possibility to change the trajectory of a child’s academic outcome and possibly life.

Editor’s note: The Duke Endowment supports the work of EducationNC.