|

|

The State Board of Education got an update Thursday on the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) plan to deploy literacy coaches into districts. It also heard from a leader of Mississippi’s science of reading implementation, offering a comparison to the state whose science of reading law North Carolina’s is loosely based.

The update to the Board comes amid persistent questions as North Carolina traverses its new literacy journey: Why follow Mississippi’s lead? Why focus on Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS)? Was it necessary to do this right now, given what teachers and schools are dealing with? Was it necessary at all?

On Thursday, leaders of the initiative for DPI took a moment to revisit the state’s “why,” set expectations, and clarify where the state is headed.

“This approach is slightly different than Mississippi because we’re deploying statewide and moving at a different pace,” said Amy Rhyne, DPI’s director of the Office of Early Learning. Rhyne said North Carolina is incorporating what it believes worked in Mississippi while trying to benefit from lessons Mississippi needed to learn as an early adopter of this statewide approach to literacy instruction.

Where is North Carolina in the implementation process?

Although it’s been a year since North Carolina enacted its science of reading law, the 2022-23 school year is the first in which schools are expected to start implementing research-based instruction. Full implementation of the law is not expected before 2024-25.

On Thursday, Rhyne tried to set expectations while articulating DPI’s vision for the upcoming year. She said her team is operating on a continuous improvement model, learning as implementation rolls out.

So far, two cohorts have started LETRS training with the third starting this month. Reports have varied from the field. Some teachers report that their colleagues aren’t taking the training seriously, while State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt says encouraging data is forthcoming and Rhyne adds that teachers who are well into the training say they wished they had it sooner.

In emails received by EdNC, some teachers report colleagues teaming up to distribute LETRS assignments so they don’t have to do all of the work. Others say teachers are doing the bare minimum to stay on pace.

In contrast, DPI has heard from district leaders and teachers that LETRS training has either introduced them to new ideas or solidified prior knowledge. At the meeting, Board Member Wendell Hall said he was against LETRS training initially because the teachers he spoke to were not happy with it. He’s now changed his mind, since those same teachers have told them they now wish they had the training sooner.

“That whole attitude of pushback has changed, which has allowed me to change my thinking,” he said.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Truitt said Amplify, owner of the mCLASS assessment tool the state provides for districts, briefed her on assessment data from last year. Truitt initially teased that data earlier in the week while speaking to the House Select Committee on an Education System for North Carolina’s Future. During that talk, she used slides that contained an error.

The corrected data, however, shows promise, she said. She said the data, which Amplify is expected to release at the end of the month, shows bigger gains for students taught by teachers in cohorts 1 and 2 of LETRS than those in cohort 3.

Although it’s created excitement within DPI, Rhyne acknowledged the data won’t show a causal relationship between LETRS training and the gains. However, Rhyne said it indicates the state is headed in a good direction and that teachers are getting the job done despite all they are dealing with.

School-based coaching biggest difference between North Carolina’s approach and Mississippi’s

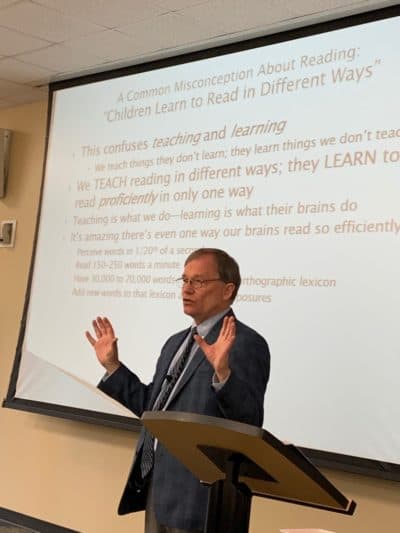

Prior to Rhyne’s presentation, the State Board heard from Kymyona Burk, the former literacy director in Mississippi who spearheaded that state’s implementation efforts. During her presentation, Burk talked about the impact of hiring and deploying school-based coaches to the lowest-performing schools in the state.

James Ford, a member of the State Board, and Eugenia Floyd, the 2021 state teacher of the year who now serves as an adviser to the State Board, wondered why North Carolina isn’t doing the same.

Rhyne said North Carolina’s plan for coaching starts at the district level and is expected to trickle down to schools gradually over time as data provides guidance on where coaches are most needed. It’s part of the whole-state approach Rhyne had previously discussed — getting some help to every district before focusing on the highest-need schools (as Mississippi started out doing).

The 115 district coaches in North Carolina, called early literacy specialists, will coordinate communication and implementation between districts and DPI’s regional literacy coordinators (two in each of the state’s eight regions), who work directly with DPI’s Office of Early Learning.

The plan is to use early literacy specialists in a dual role — three to four days focused at the district level and one to two days of school-based coaching where the specialist determines students are most in need. In the meantime, school instructional coaches will provide coaching support to teachers, though Rhyne said about 19 districts do not have instructional coaches.

It’s an equality-first approach, Rhyne acknowledged, adding that the intent is to move to a more equity-focused model perhaps as soon as next year.

“This is kind of that ‘core’ year where we’re focusing on getting everyone on the same page and being strategic at the same time,” Rhyne said. “Looking at next year, we may come back and look at the data and say now we need to shift a little more to strategic and intensive, which means a little more involved in the school level because the district will have the processes in place at that point.”

Ford asked about where there may not be instructional coaches to provide teachers with in-classroom support. He asked whether there was a plan to get someone into those buildings at some point. Rhyne confirmed that this was the plan, and that the regional- and district-level personnel will be able to identify where coaches are most needed.

That may include districts with no instructional coaches, and may also include districts with high-performing schools. Rhyne said the data can easily tell where low-performing schools are but it’s harder to identify where high-performing schools are masking needs for subgroups of students. Having early literacy specialists in each district will help identify the students who need more support.

“So are we looking at that and paying attention to, not only the high-performing school but the subgroups within that school that’s not making the same growth,” Rhyne said. “All that to say, we have that process to have those conversations and figure out how to get down all the way to that school level.”

The early literacy specialists will use a Partnership Support Cycle to drive decision-making. The support cycle model is also designed for use by both teachers and Office of Early Learning staff, so eventually Rhyne hopes it will be used at every level of student and teacher engagement.

“The questions around the data are awesome and really helping us do the work for our children,” said Floyd, who also teaches literacy in Chapel-Hill Carrboro City Schools.

Why are we hearing about Mississippi, and what guidance did its former literacy director provide?

We’ve written a lot about Mississippi’s literacy story, here and here. According to lawmakers and policymakers, Mississippi is worth studying because of what happened on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) after they passed its science of reading law.

Not only did its fourth graders show the nation’s biggest gains in 2019, its low-income students and students of color gained more than their peers. That year was the first where Mississippi fourth graders were students who had spent their entire elementary schooling receiving instruction according to their 2013 law.

Students haven’t taken the NAEP since 2019 due to the pandemic, so the next opportunity to assess where Mississippi stands will be spring 2023.

Burk said Mississippi’s approach included LETRS training, school-based coaching, individual reading plans, parent communication, and early identification.

She said that the state walked a line between providing assistance and pulling back to let schools take leadership, part of a “gradual release” approach.

Mississippi hired and trained literacy coaches to place in its school buildings — one coach for two schools — prior to LETRS training for its teachers. It began, in the first year of LETRS training for teachers, with 29 coaches covering 50 schools and grew, at its peak, to 80 coaches covering 182 schools.

Some of the biggest lessons, Burk said, were the importance of clearly communicating expectations to districts, outreach to parents and communities, and transparency in everything they did.

Another lesson she passed on: Outcomes won’t change overnight.

“As you are on this journey, you will begin to see gains that are happening in schools — at the local level,” Burk said. “And some of those gains may happen quickly. They may happen within a year or two years. But as a state, as you’re moving the state forward, that may take a little time.”

A State Board-funded tutoring initiative reports on its first year

This past year, the North Carolina Education Corps leveraged about 20 coaches to train and support 237 tutors who served about 3,000 students across the state. Ed Corps, which you can read more about here, deployed tutors to 22 districts and one charter school.

Ed Corps Executive Director John-Paul Smith told the State Board that this year the organization is hoping to deploy 500 tutors and has a goal of growing to 1,000 tutors the following year. Tutors have come from three primary areas, Smith said: community college and college students, parents and family members, and retired teachers. Anyone interested in applying to become a tutor or learning more can do so here.

“We are very grounded in this belief that we want to make sure that all students in the state of North Carolina have the full support they need to thrive,” Smith said. “The way that we contribute to this is to help recruit and train and provide ongoing coaching and support for high-impact literacy tutors.”

Recommended reading