Share this story

- “I've said to my colleagues a couple of times, I wish I had this information as a beginning teacher. I wish that it were a requirement for beginning teachers as a college level class,” said one fourth grade teacher.

- A year after North Carolina enacted its newest reading law, and eight months after LETRS training began, teacher reaction to the effort is still mixed.

There was trepidation in the air in Davie County last August when students and teachers started school in person for the first time in nearly two years. Teachers were navigating shifting COVID protocols, tracking missing students, paying close attention to the mental states of the kids, and finding time to wipe down surfaces and help with mask fitting.

And then there was the business of learning, where teachers negotiated the demands of catching kids up academically while aiming for the standards on which students would eventually be tested.

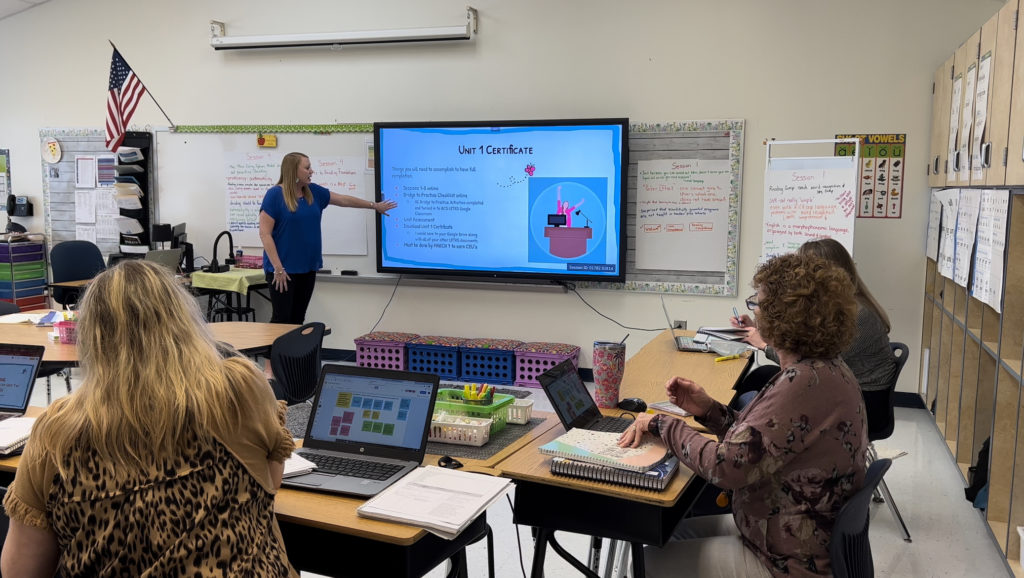

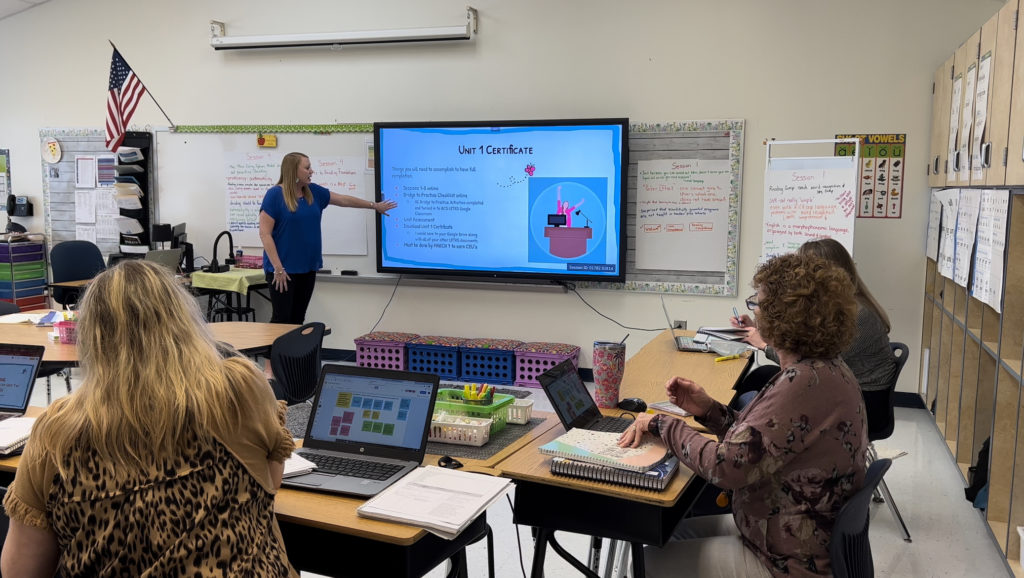

That was the climate when Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training began.

In April 2021, the legislature passed and Gov. Roy Cooper signed a bill mandating that literacy instruction be based on a body of research called the science of reading. LETRS is a program used for the training of teachers and administrators on what the research says and classroom practices.

Some teachers have been skeptical. Was this necessary? Many have been nervous. Even if this training would help, did it have to happen now?

“It’s such a difficult year – all the challenges we all face with everything that has happened over the last couple years,” first grade teacher Megan Cooper said at a recent Department of Public Instruction (DPI) web panel. “I also worried about where I would fit in the time to do this college level coursework that required so much of us.”

The days were already packed tight, and LETRS is intense — 160 hours over two years of learning about the brain and the building blocks of language. For Megan Cooper, the worry has given way to excitement — a sentiment shared by many teachers across the state, but not all.

A year after North Carolina enacted its newest reading law, and eight months after LETRS training began, teacher reaction to the effort is still mixed. Some question the efficacy of LETRS, and they recently found support from one literacy expert.

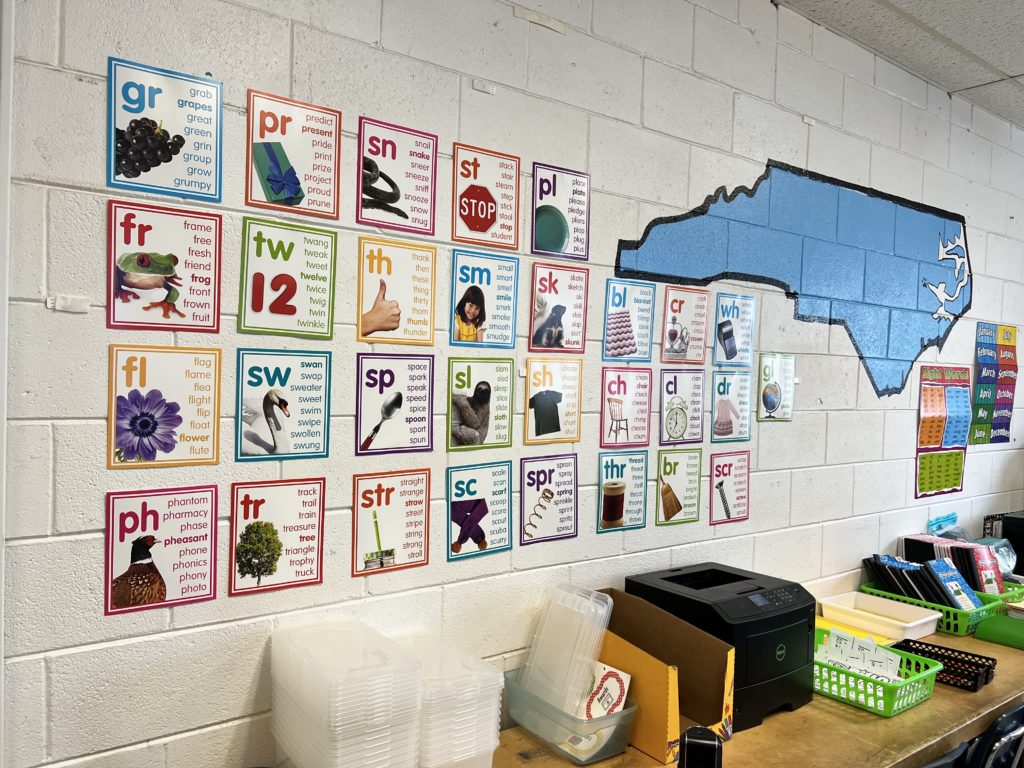

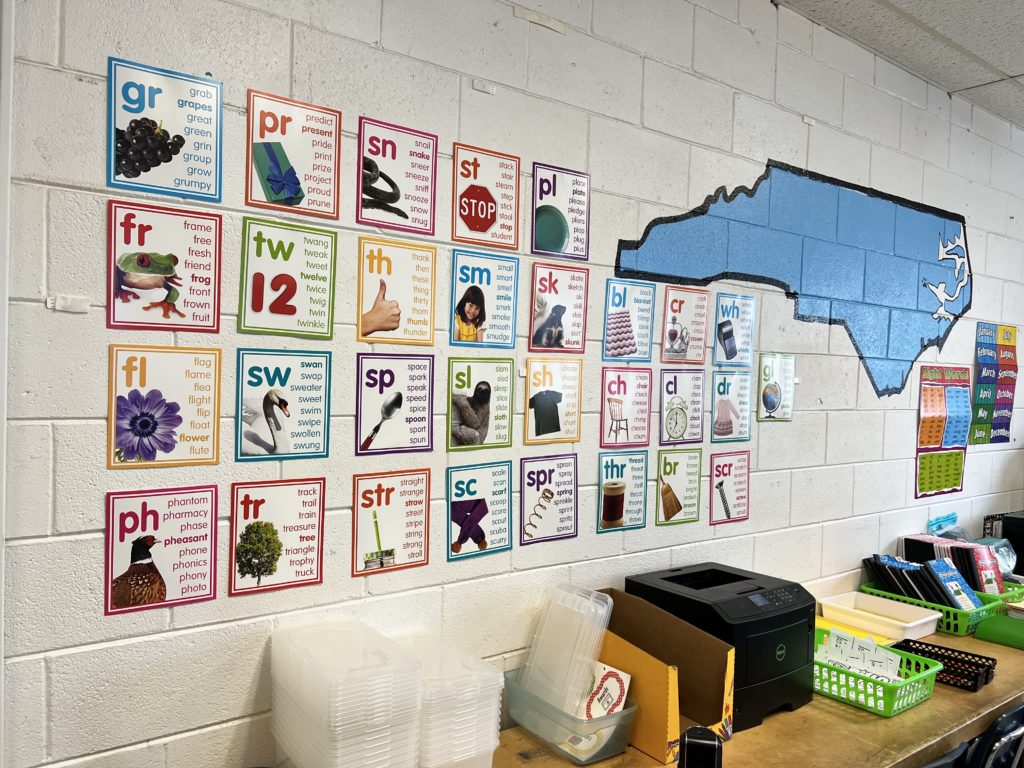

But in several districts across the state, LETRS is moving teachers away from overdependence on curriculum and toward better diagnosis of difficulties. The rollout of training statewide is also creating a shared language around reading instruction and helping districts collaborate.

LETRS isn’t the only solution, but it’s working in many districts

Mark Seidenberg, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin, makes the point that not every teacher needs nor is ready to digest the breadth and depth of the LETRS program. That echoes what some literacy leaders in the state told EdNC about LETRS shortly after the bill was ratified.

Seidenberg cites other available professional development courses that are shorter and less intense. In North Carolina, for example, courses are available through the Hill Learning Center or the North Carolina State Improvement Project.

But there are also a lot of teachers, like Cooper and her colleagues, who are finding a rhythm for getting through the training and appreciate the rigor of the coursework. They are translating the work into more effective use of class time.

“As I’ve gotten into it, it is in-depth and it is time consuming, but I have found it to be very useful information,” Davie County fourth-grade teacher Leigh Anne Davis said. “I’ve said to my colleagues a couple of times, I wish I had this information as a beginning teacher. I wish that it were a requirement for beginning teachers as a college level class.”

Tyler Goodwin, a third-grade teacher in Columbus County Schools, said that LETRS training helps him understand what’s happening when students are struggling in his class.

“And [it’s] allowed me to dive a little deeper into some of the assessments and things that I have been using in the classroom, such as mCLASS,” he said. “It’s helped me to go a little bit further to see where my students’ weaknesses are at.”

Timing and implementation disparities makes assessing impact difficult

Only two cohorts of school districts have begun the training — about half of the roughly 50,000 educators that will ultimately participate. Among those that have, most are barely past the first two units — the more theoretical part of the program that focuses on “why” more than “how.”

Lynsey Fowler, an instructional support specialist in Union County Public Schools, has gotten to the “how” units — the ones that talk about classroom practices and prompt teachers to try them out on small, “case study” groups of students.

“I was pretty nervous about that as we first started because it was so technical,” she said of the first two units. “But once you learn the science behind everything, and how the brain works and how students learn to read, that really helps provide that foundation for the rest of the content. And after those technical sessions, the book really starts going into practical application.

“It talks about reading difficulties and interventions and assessments and just a bunch of other literacy components that you can take straight to the classroom.”

But LETRS implementation doesn’t look the same in every district. While the state is paying for the training, has allocated funds to each district to support the training, and is offering guidance on best practices, the implementation of LETRS is largely directed by district leaders.

Some districts are providing teachers with time during the work day — through planning time or teacher workdays. Others aren’t. Some are offering supplemental pay, anywhere from $300 to $2,000, either using state funds allocated under the law or Title I dollars. Others aren’t.

“I think it’s worthy for us to think about: How do we best serve districts so that, from one district you may have all these great things and another it’s not,” Kisha Clemons, former state principal of the year, said during the March State Board of Education meeting. “There’s inequities in that and our teachers need our help, so I think we still need to consider new ways to support our districts and our schools.”

The disparity leads to some pockets where teachers are eager as they move through the training, finding a couple days a week to devote up to an hour of going through LETRS book work and watching LETRS videos. In other pockets, teachers are scrambling and overwhelmed. Some districts have reached out to DPI to inquire about delaying the training.

Office of Early Learning Director Amy Rhyne said DPI is talking to local leaders about purposeful abandonment — finding lower priority items that can be postponed or using professional learning community (PLC) time more effectively. She said some districts are finding ways to rotate non-academic duties to open up time for teachers.

That’s the approach DPI is encouraging — supporting teachers to find more time. Delaying the training isn’t an option — not only is there a timeline in the contract for LETRS, but Rhyne made the point that every delay means more students not getting what they need to become proficient readers.

“We’re committed to these kiddos and their parents,” Rhyne told a group of school and district leaders at a North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching (NCCAT) literacy conference late last year.

“If you listen to the stories of these parents when their children can’t read and they’re struggling, it breaks your heart,” she said. “And when you look at numbers like 37,000 children that were not proficient last year in just one grade level, that hurts. So we can’t wait. It’s hard and I get it, but let’s dig in and we’ll help you and we’ll be your advocate and be as flexible as possible.”

What’s working in some districts

Teachers in districts where principals are blocking time off during school days report that staying on pace with the one-to-two hour per week commitment has been easier. Megan Long, a second-grade teacher in Union County, says she uses school time to work on certain activities and spends about an hour per lesson at home working through the LETRS book and videos.

“I like to do the reading with the online modules side-by-side because they do go hand in hand,” she said. “And I’ve also found that as I progress through LETRS that I find the content is more something that I’m interested in. So I also kind of look forward to it now because the learning, to me, is something that I can definitely use in my own classroom.”

That’s also been the case for Davis in Davie County. As a fourth-grade teacher, she was used to focusing on comprehension strategies for her students. LETRS has helped her identify word recognition deficiencies in her students so she can provide interventions.

“Going through LETRS, I understand better now that when students can’t comprehend, that may be part of the issue, but it may go back to the phonological and phonemic issues,” she said. Davis is seeing more of these issues since the pandemic and has reorganized her lesson plans to make more time for teaching decoding skills.

For Fowler in Union County, the LETRS training has created a buzz. Instructional coaches in Union County, like several across the state, opted to join teachers in doing the training.

“It’s just exciting to see teachers come to PLCs,” she said. “They’re excited about what they’re learning. They’re having great discussions about how they’re applying everything that they have learned in their classrooms.”