Share this story

- Educators in North Carolina have asked for ground-level support to implement the science of reading law. We're watching for school-based coaching, intervention support, teacher assistants, and instructional material during this short session.

- When it comes to implementing the new reading law, "we have to listen to teachers. ... We are boots on the ground. We are the ones out there in the field, and those teachers are in those classrooms. They know."

|

|

Funding aimed at improving student reading proficiency is expected to get a boost during the legislative short session, and educators are watching to see if that spending is designed to directly impact instruction in the classroom.

The state enacted a science of reading law in April 2021. It amended the 2012 Read to Achieve law, which saw basic reading proficiency tick up only two percent over seven years after its passage. A third-party evaluator said the original Read to Achieve suffered from disparate implementation efforts across districts.

That’s the question for North Carolina in this moment: How will it implement the new law equitably across the state? What will have the most impact toward desired outcomes?

The new law placed mandates on educator preparation institutions, teacher training, individual reading plans, and literacy intervention plans. Most notably, it signaled a shift away from ineffective instruction practices rampant in North Carolina elementary schools and now seeks to ground instruction in a body of research on how the brain learns to read and write.

North Carolina was among a growing list of states passing science of reading laws. Some have criticized science of reading legislation as trying to legislate student outcomes — especially when laws rely too heavily on holding students back a grade. Others say literacy is one place where state law can make a difference — if it is paired with supports that reach classroom teachers and help them do their jobs well.

To that point, many experts — including N.C. State University Associate Professor and UNC System Literacy Fellow Dennis Davis — agree that the intention of these laws won’t be achieved unless implementation efforts focus on translating teacher knowledge into effective classroom practices.

For that, educators in North Carolina have asked for ground-level support. In fact, they were asking for these prior to passage of the law. These primarily fall under four categories: school-based coaching, intervention support, teacher assistants, and instructional material.

Lisa Brown, literacy/multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS)/professional development coordinator for Columbus County Schools, said she hopes legislators hear these requests — because a year into state implementation of the law, districts and schools are starting to see the pain points as they begin classroom implementation going into next school year.

“I think we’re actually at a point where people are starting to listen,” she said. “And I think that that’s important. We have to do that every day, we have to listen to teachers. And we have to hear them and absorb what they’re saying and see how we can better that situation. … We are boots on the ground. We are the ones out there in the field, and those teachers are in those classrooms. They know.”

School-based coaching

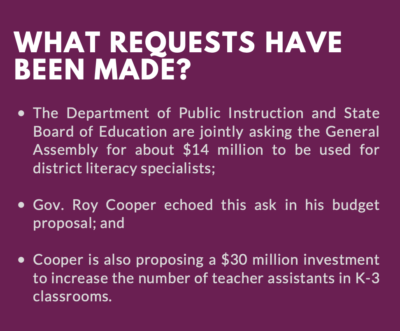

The Department of Public Instruction (DPI) has not announced plans for placing school-based coaches in the field. It is, however, asking the General Assembly for $14 million to hire and place 115 literacy specialists across the state’s 115 school districts.

The specialists are part of a four-tiered model of supports DPI is designing, which includes supports at the state, regional and district levels. The fourth level of support, school level, will utilize existing staff in schools who are identified as literacy leads and would act as coaching support for the school.

Some district leaders are eagerly watching what the General Assembly will dowith the $14 million ask, saying these literacy specialists are needed liaisons between districts and DPI because district leaders are sometimes overwhelmed by the amount of information and resources coming from the state.

But others wonder if this nod to equality — one literacy specialist for each district — comes at the expense of equity.

“I think that one per district is going to have varying impact because you have districts that have four schools and you have districts that have 144 schools,” said Jessica Garner, director of college readiness for Union County Public Schools. “Providing one person seems equal, but maybe not equitable based on the size of various districts.

“I know it’s challenging, and I know there’s a limited pot of money. I think it could be helpful — at this point any assistance that can be given to districts would be helpful in implementing this.”

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

The pot of money isn’t as limited this year, as the state reported a $6 billion surplus heading into the legislative short session. For context, each literacy specialist position costs the state about $120,000 and the DPI Office of Early Learning Director Amy Rhyne told the State Board of Education this month that it would cost $133 million to put a literacy coach in every elementary school.

That said, the short session is not typically the time when large funding allocations are granted. The literacy specialists may be the first of a larger request for next long session.

While neither DPI nor the State Board are pushing for hiring school-based coaches at the state level yet, North Carolina does have a coaching program that Gov. Roy Cooper’s budget proposes to continue funding with a $5 million allocation.

The New Teacher Support Program (NTSP) was implemented in 2011 and employs 50 instructional coaches in coordination with 11 of the state’s public universities. It places coaches in schools in 62 districts. Some of these supports for beginning teachers are school-based partnerships and some are district based.

“All that said, the support NTSP provides teachers, regardless of the type of partnership, takes place exclusively at the school level – in the space where teachers are working with children,” Patrick Conetta, NTSP’s director of teacher induction and development, said. “Perhaps a more accurate term would be ‘classroom-based support.’ We have found that interactions and support at this level enhance coaches’ ability to model lesson [and] co-teach with their assigned teacher.”

This year, NTSP started professional development for its coaches in the science of reading.

Literacy intervention assistance

In addition to coaches, who work with teachers at the classroom level to help translate knowledge into effective practice, teachers say they need support implementing interventions for students with greater needs.

Interventions are called for when a student is stuck at some point in their reading development. An interventionist — or the classroom teacher if there is no interventionist — uses assessment data and observation to design instruction to help kids get un-stuck.

Under the science of reading law, districts are required to submit intervention plans to the state, on which DPI would provide feedback.

Last year, former state teacher of the year Mariah Morris told EdNC that funding for both school-based coaches and interventionists are needed. When she made the comments, she was in district leadership at Moore County Schools. Now, she is a K-5 literacy facilitator in Orange County Schools.

“Our state needs to fund them both [coaches and interventionists] if we want to move the needle on reading instruction,” Morris said. “Unfortunately, we don’t have state funding for a lot of these positions, and a lot of districts are forced to only have coaches or interventionists at Title I schools. That’s a huge blind spot in our goal to move the needle on reading instruction.”

Most of the dollars districts spend toward literacy interventions are spent on programs. But while funding for interventionists is important, it can’t come at the expense of needed programs, Morris said.

Beth Anderson, executive director of Hill Learning Center, feels this tension. Hill supports students in 42 counties through its HillRAP reading intervention. In 2018, DPI released state Read to Achieve funds for training educators in HillRAP and research-based resources and strategies for identifying dyslexia and supporting struggling readers.

But this funding source is doing a lot of work. The same pot of money is used to support students who have been retained in a grade level more than once, by some districts to compensate teachers with stipends for the extra work they are doing for LETRS training, and to purchase instructional materials.

Teacher Assistants

Since the 2008-09 school year, the number of teacher assistants in North Carolina public schools has dropped by about 10,000, according to data from DPI. That’s a devastating trend, several teachers said, particularly during implementation of the science of reading law.

When the General Assembly mandated K-3 class sizes average 18 students a few years ago, the law did not include funding for teachers and teacher assistants. So, K-3 class sizes shrunk and fourth and fifth grade class sizes grew as more of those teachers were used for the lower grades. Since the pandemic, teachers have reported a rise in upper grades elementary teachers asked to teach lower grades, as well.

Susan King, a teacher in Iredell-Statesville Schools, said elementary teachers need more adults in the classroom in order to manage the number of students and focus on the instruction promoted under the science of reading law.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

During the long session, two companion bills were introduced in the General Assembly to address this need. The K-3 Literacy and Improvement Act, introduced in the Senate by three Democratic senators as Senate Bill 359 and introduced in the House by four Democratic representatives as House Bill 420, called for $271 million to put a teacher assistant in every K-2 classroom and one teacher assistant for every three third-grade classrooms.

Neither bill met the crossover deadline, which means that they weren’t voted out of their respective chambers in time to be considered any longer. However, Cooper’s proposed budget calls for $30 million in increased funding for teacher assistants in K-3 classrooms, which educators say is needed, along with support for fourth and fifth grade classrooms where the number of students is not capped.

Instructional Materials

High-quality and evidence-aligned instructional materials can also play a critical role in boosting student literacy achievement. Guilford County Schools Senior Director of Literacy and MTSS Joy Cantey told EdNC last year that districts need support selecting — and purchasing — effective curriculum.

“Districts need support with selecting curriculum,” Cantey said then. “… The state needs to fund a curriculum. Districts can certainly have choice, and it doesn’t need to be the same curriculum in every single district, but there needs to be some funding for districts to adopt a comprehensive curriculum for literacy.”

Rhyne said DPI plans to create a rubric that will help districts choose evidence-based, aligned curriculum. But some districts already spent money on curriculum before the science of reading law was passed.

Teachers also need funding for other evidence-based materials for their classrooms — like decodable readers that help students practice word recognition.

“All of our teachers, they are getting this training and learning what they need to do differently and they are buying into the training,” Garner said. “And now they’re saying, ‘Oh man, I need some more resources.’ And so I think that if there’s one thing that could be provided, it would be money for districts to purchase resources to support the implementation of the science of reading.”

Recommended reading