This is part of a series on developmental education in North Carolina. Click here to read the rest of the series.

Joel Marquez remembers sitting in his living room watching television as a boy and seeing a fighter squadron do stunts in the air.

“I saw all the pilots in there and I saw how cool that was, and I said, ‘Mom, I want to be a pilot!'”

Marquez still holds that dream. His goal is to get a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and join the Air Force. For Marquez, that plan starts at Catawba Valley Community College (CVCC).

Marquez grew up in New York and moved to North Carolina with his family when he was young. His mother, who had been a teacher in New York, decided to homeschool him for most of middle and high school.

When the time came to think about college, Marquez did his research.

“I was looking at colleges in my area that suited my needs for my degree … and in looking at colleges, I found CVCC,” Marquez said. “And I saw that they have a transferrable program, the associate in science, and I could transfer to a university and finish off my four-year degree.”

Marquez enrolled at CVCC in the fall of 2019. His plan was to get his associate of science there and then transfer to the engineering program at either North Carolina State University or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

But he hit a roadblock when he was told he did not meet the requirements to enroll in the college-level English classes he needed for his degree.

What is developmental education?

Every year, students like Marquez come to community colleges with hopes and dreams. And every year, they find themselves in the same situation as Marquez — told that they do not qualify to take college-level classes. Some are returning to school after decades in the workforce. Others didn’t do particularly well in high school. Others simply didn’t do well on placement tests.

Community colleges in North Carolina are open door institutions, meaning they accept all qualified students. Because of that, they get students at all levels of academic preparation. To make sure students are ready for college-level classes, community colleges across the country offer what are called developmental or remedial education courses.

These courses are designed to prepare students for college-level math and English classes. And while they are taught through the college, developmental courses are noncredit courses, meaning students do not receive college credit for taking them.

The first step in developmental education is placement — colleges have to create some way to determine who is deemed ready to take college-level courses and who is not. The second is the actual developmental courses for those deemed unprepared. Incoming students who are placed in developmental courses must pass those to demonstrate they are ready to move on to college-level courses.

Because he was homeschooled, Marquez said he did not have a high school grade point average (GPA), one of the ways community college students in North Carolina can qualify to take college-level courses. So he took a diagnostic placement test instead and fell just short of the required score to take English 111, the college-level course he needed. But he had an option other than a remedial course.

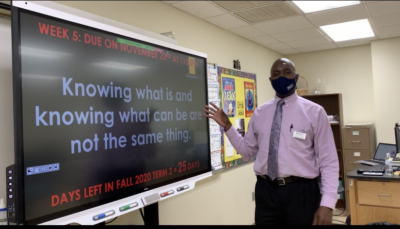

Thanks to a recent initiative called RISE (Reinforced Instruction for Student Excellence), Marquez was able to enroll in English 111 as long as he also enrolled in a corequisite course designed to provide extra support.

RISE is the latest reform in a decade that has seen significant changes to developmental education both nationally and in North Carolina. These reforms have focused on getting more students to and through college-level courses.

While the majority of the state’s 58 community colleges have implemented RISE, the North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents voted in October 2020 to pause system-wide implementation of RISE, which was supposed to take place by fall 2020, until spring 2022.

This piece is the first in a series that takes a look at developmental education in North Carolina — where we are now, how we got here, and what’s next. This article looks at the developmental education reforms over the past decade that have led to RISE.

The ‘data bombs’ that spurred reform

Had he been born a decade earlier, Marquez would have had to take and pass at least one semester-long developmental education course before he could take the English courses required for his degree.

“I would have had to stall an extra semester,” Marquez said. “And for me to be held back because of a requirement that I didn’t necessarily need … I would have been very frustrated.”

As Scott Ralls, now president of Wake Technical Community College, was taking the helm at the system office in 2008, incoming community college students were required to take one of two national placement tests — Compass, run by ACT, or AccuPlacer, run by the College Board. Students who were deemed in need of remediation were placed in a math, reading, and/or writing developmental education course sequence based on their test results. Some students could face as many as four semesters, or two years, of developmental education courses before they could take college-level classes.

As part of Ralls’ and the system’s SuccessNC initiative, system leaders held a listening tour across the 58 colleges to identify best practices and barriers to student success. One of the barriers they identified was developmental education.

After the tour, Ralls declared developmental education “the Bermuda Triangle of community colleges,” according to the SuccessNC Final Report published in 2013.

Meanwhile, new data showed just how few students were making it through developmental education and into college-level classes.

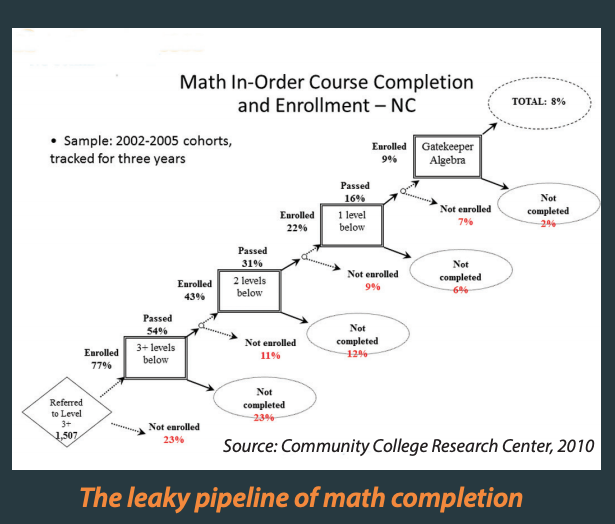

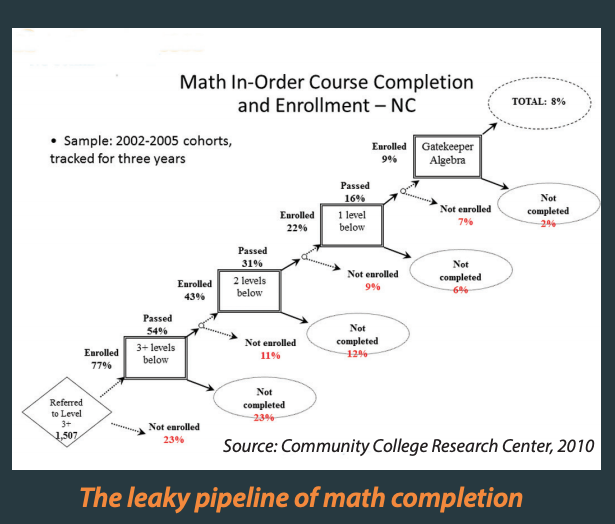

In 2010, research from the Community College Research Center (CCRC) on North Carolina showed that only 8% of students who placed three levels or more below college readiness in math ever completed a college-level math class. One in five of those students (23%) never even enrolled in a developmental math course.

“What we found is that very few students are able to get to the introductory college-level or gateway course,” said Nikki Edgecombe, senior research scholar and research professor at CCRC. “We had created this long sequence of courses and students were not persisting.”

At the same time, data showed that in 2011, 69% of recent North Carolina high school graduates coming into community colleges placed into at least one developmental course. Ralls recalled being at a meeting with then State Board of Education Chair Bill Harrison, who said that statistic was the one thing they needed to be talking about.

“All of a sudden it was off to the races,” Ralls said. “That number became very public.”

CCRC research also found that the national placement tests were putting more students in developmental education than necessary.

“Research by CCRC on North Carolina indicated how terribly unpredictive those [placement tests] were,” Ralls said. “Three out of 10 students were misplaced into developmental education.”

“We had these huge data bombs, and we had to do something about it.”

– Scott Ralls

In addition to the data, system leaders were also looking at the cost of developmental education. North Carolina taxpayers were paying for students’ K-12 education and then paying for those same students to go through, at times, years of developmental education at community colleges.

According to the SuccessNC Final Report, developmental education consumed around 10% of community colleges’ budgets at the time. A 2015 Hunt Institute report placed the annual cost of developmental education to the state at $125 million in 2012.

Developmental education was costing students money and time as well. Students had to pay college tuition for classes that did not earn them college credit. In addition, according to the SuccessNC report, new caps on federal financial aid meant that some students were burning through their financial aid money in their developmental classes.

All of these factors pushed Ralls and system leaders to create the Developmental Education Initiative (DEI). The initiative focused on getting more students in college-level classes and redesigning developmental courses so they were targeted to what students needed and students could move more quickly through them.

Modularization and multiple measures

CCRC’s research on student progression through the math developmental courses showed a “leaky pipeline.” Students were dropping out of developmental education and not returning.

“Systems began to look at ways in which they could streamline the sequence of courses, creating fewer exit points for students and thus hopefully allowing more students to make it to their college-level coursework,” Edgecombe said.

Starting with math, DEI reformed the developmental course sequence into eight modules rather than four semester-long courses. “By improving alignment and reducing redundancy, the team shortened developmental math by one-third and created modules that emphasize conceptual understanding of math similar to the Common Core State Standards adopted by K-12,” the SuccessNC report explains.

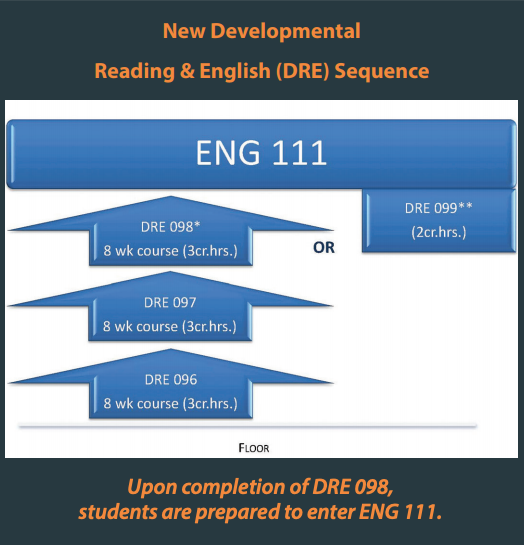

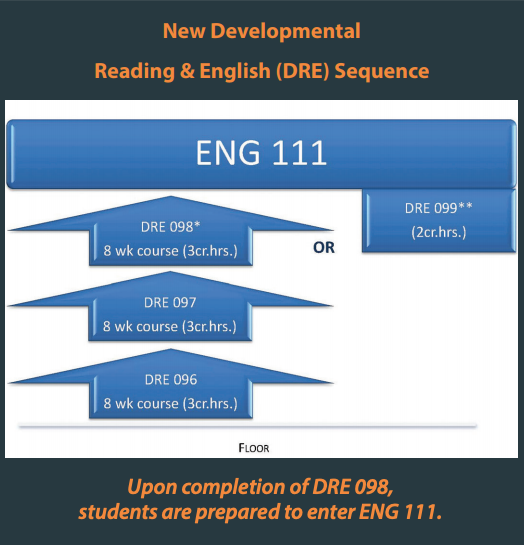

By fall 2013, all 58 North Carolina community colleges switched to these modules. DEI then set about doing the same thing with the reading and writing developmental course sequence. Instead of having separate courses, they combined reading and writing into three eight-week courses. These were adopted by all 58 colleges by fall 2014.

At the same time, the North Carolina Community College System asked CRCC to help it develop a new placement system.

“CCRC said you should use multiple different measures and different things [for placement],” Ralls said. “We put it back to them and said, ‘Okay, we’re flying the airplane here. Tell us what to use.'”

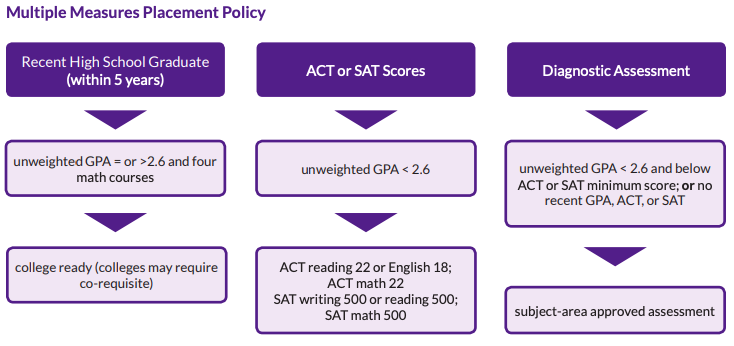

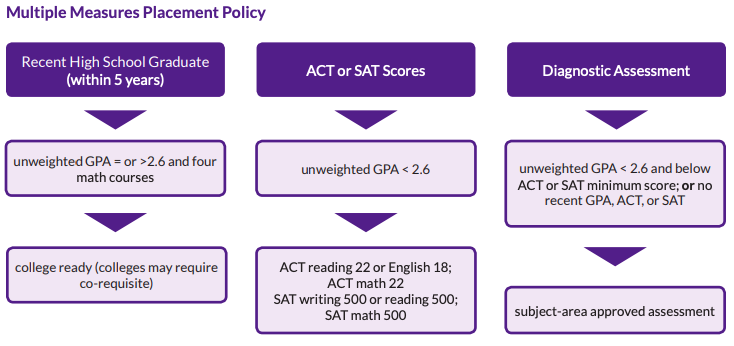

CRCC found that the strongest predictor of college success was not the placement test score but high school GPA. The system decided to abandon the national placement tests and create a system where students had multiple ways to place into college-level courses, called “Multiple Measures for Placement.” The measures included high school GPA, ACT or SAT scores, and a new diagnostic assessment called the North Carolina Diagnostic Assessment and Placement test (NC DAP).

The system held a competition to determine who would develop the NC DAP and awarded the contract to the College Board.

The diagnostic test was designed to coordinate with the curriculum reform and tell colleges where to place students among the math and English modules.

“The point was being diagnostic,” Ralls said. “It wouldn’t just give you a cut score of whether you were in developmental or not. It would say specifically here’s the things you did not get.”

Community colleges could start implementing the multiple measures policy in fall 2013 and were given until fall 2016 to do so.

Not a silver bullet

By 2016, North Carolina’s 58 community colleges had gone through multiple stages of developmental education reform.

“The community college systems of Virginia and North Carolina are national leaders in statewide efforts to improve developmental education,” a 2015 CCRC report read. That report found some initial signs of success in Virginia, but said it was too early to tell in North Carolina.

One sign of success in North Carolina, however, was the decline in students enrolling in developmental education.

“Within a year or two, our enrollment had declined, and we could pinpoint it back to students not spinning their wheels in developmental education,” Ralls said.

The 2015 Hunt Institute report found that enrollment in developmental education declined over 50% from 2009-10 to 2013-14, and that meant that state appropriations to colleges for developmental education declined from about $96.1 million in 2009-10 to $42.9 million in 2013-14.

The system used the savings as a bargaining chip to get more funding for costly programs, Ralls said. In 2014, the General Assembly appropriated $15.1 million to create a fourth tier of funding for higher-cost community college programs such as health care.

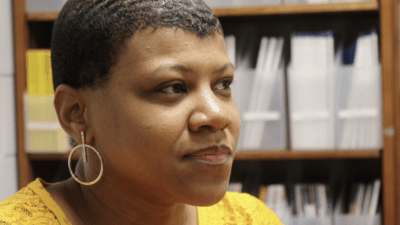

Statewide evaluation was difficult, said Lisa Chapman, who was at the system office at the time, because colleges were implementing the reforms at different times. Yet as colleges looked into their data, they found students were still getting stuck in developmental education, particularly the students requiring the most remediation.

“It was better than what we had before,” Chapman said. “In general, we had more students completing [college-level] courses. The success rate wasn’t leaps and bounds better, but there were more students getting into those courses, and the success rate was not worse.”

As they disaggregated the data, however, “We were seeing that we were still not helping those that had the greatest need as much as we needed to,” Chapman said.

Ralls said he wasn’t sure the changes were “solving the problems for students who didn’t come in with a strong foundation.”

The move toward a corequisite model

Ralls left the system in 2015 to become president of Northern Virginia Community College. Several things happened from 2015 to 2017-18 that precipitated another big change in developmental education, this time toward what’s called a corequisite model.

First, the General Assembly passed legislation in 2015 mandating that the State Board of Community Colleges, in consultation with the State Board of Education, develop remedial courses to be taught in senior year of high school based on the colleges’ developmental math and English curriculum. Known as the Career- and College-Ready Graduates (CCRG) program, these classes would be mandatory for incoming seniors who had not demonstrated college readiness by the end of their junior year.

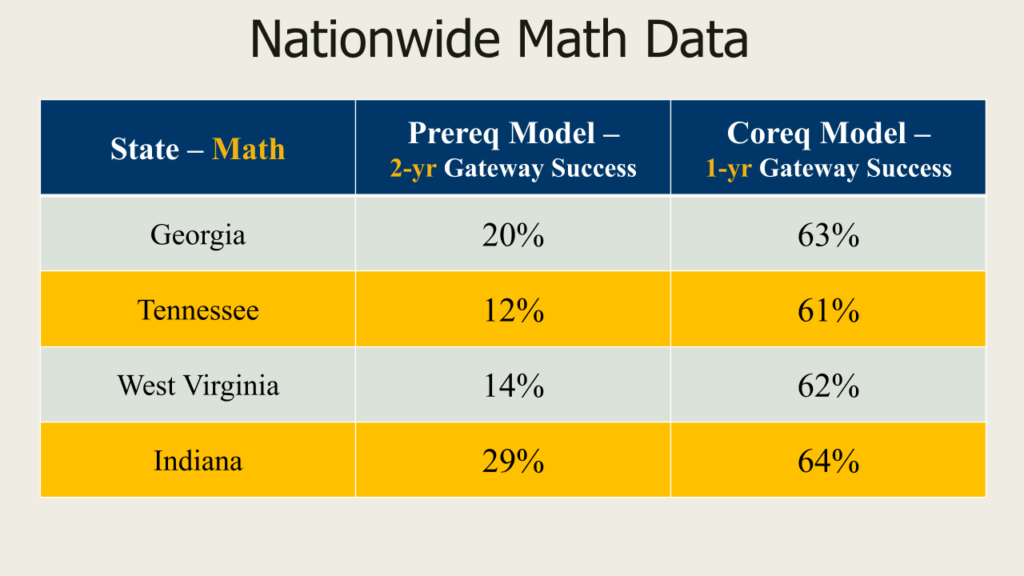

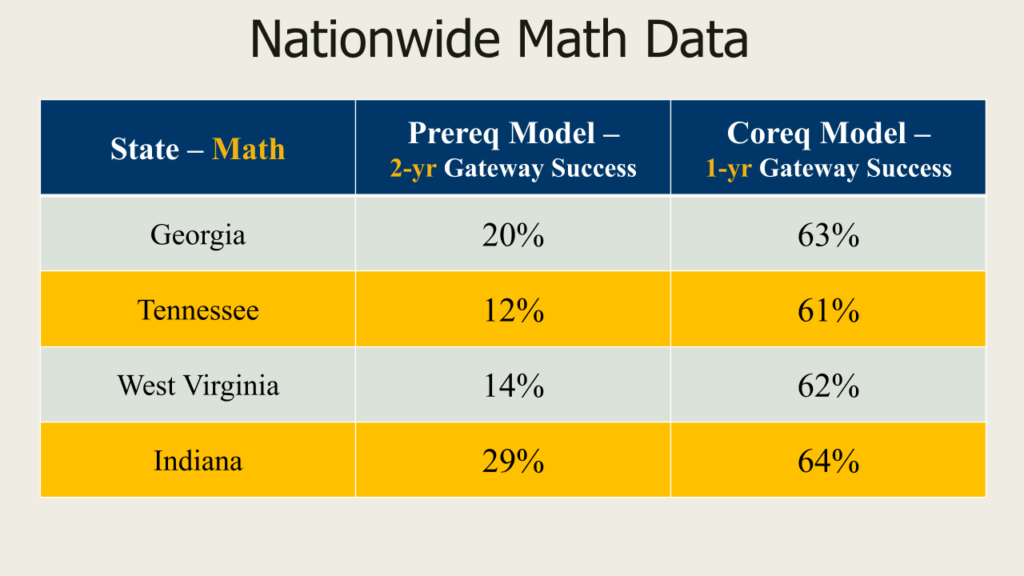

Secondly, new data from Complete College America looked at states that had implemented a corequisite model of developmental education. Such models allow students to start college-level classes immediately while they take a concurrent support class.

Tennessee had switched to that model, and the results were eye-opening, Chapman said.

“We were ahead of [Tennessee] in terms of recognizing we needed to change,” Chapman said, “but they saw great success leapfrogging us and going directly to corequisite.”

Importantly, Tennessee saw success in the students that were hardest to reach, Chapman said.

“It was data we couldn’t ignore,” she said. “We knew that what we had done had helped, but it was not enough. … So again we began to further investigate the data and then started talking about that throughout the state.”

Because they had just required a systemwide overhaul of developmental education, the system decided to take a different approach this time, said Kim Gold, senior vice president and chief academic officer at the system office.

“Rather than just jumping in with both feet and dragging all 58 colleges along, we decided to pilot this corequisite model and took volunteer colleges to do that pilot process,” Gold said.

Several colleges volunteered. From spring 2017 to spring 2018, the system worked with them to plan what would eventually become RISE. The first colleges implemented the model in spring 2019, and another group followed in fall 2019.

Catawba Valley Community College was in the initial pilot group that started implementing RISE in spring 2019, just as Marquez was looking at colleges. Marquez and several other students have since gone through the corequisite model of developmental education.

Next in this series, we will look at the nuts and bolts of RISE and what it looks like at one college. To read the rest of the series, click here.

Behind the Story

Molly Osborne and Emily Thomas reported and wrote this series. Eric Frederick, Analisa Sorrells, and Mebane Rash edited it.

Over the course of four months, we interviewed five North Carolina Community College system office staff, 10 former or current community college presidents, 18 community college administrators, 14 faculty members, 14 students, one Department of Public Instruction administrator, and nine community college researchers and national experts.