This is part of a series on developmental education in North Carolina. Click here to read the rest of the series.

When Erica Hull finishes a 12-hour shift at the hospital, she isn’t done with her day. Instead, she heads home and logs online to work on math and English coursework at Catawba Valley Community College (CVCC).

Hull is a full-time mom, Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA), and now student. Last year, she decided it was time to go back to school.

“Just to be brutally honest, I’m really tired of being a CNA,” she said. “I’m ready to move up and make a little bit more money and have that specific chosen path.”

Hull, who’s been a CNA for the last 10 years, enrolled at CVCC with the goal of becoming a certified radiology technician. Before she can start taking the classes she needs for her degree, however, she is taking remedial math and English courses meant to prepare her for college-level coursework.

“When I graduated from high school, we were still in typewriters,” Hull joked. “I didn’t have the ability to Google — I think my GPA would have been a lot higher if I did.”

Community colleges serve students coming from all walks of life, including those right out of high school and those like Hull who have been out of school for many years. To make sure students have the academic foundation to succeed in college-level classes, colleges have long used what are known as remedial or developmental education courses.

Over the past decade, North Carolina’s community colleges have overhauled developmental education after data showed students were getting stuck in remedial courses and dropping out. The latest reform, a move to what is called a corequisite model, allows students to take college-level courses at the same time as remedial courses (corequisites). Other states that have implemented corequisite models saw significant improvements in student success, prompting North Carolina to pilot this approach in spring 2019.

The plan was for all 58 community colleges to implement the corequisite model, called RISE, by fall 2020. However, community college presidents voted to delay full-scale implementation to spring 2022.

“For us to look at any project and encourage everybody not to move forward with that project is significant, particularly something that is of this large of a scale,” said Bladen Community College President Amanda Lee, who co-chairs the committee that recommended the delay of RISE.

Lee said this move was driven by not having data from the pilot schools to understand if RISE is working. Getting data has been difficult for the community college system for several reasons, but it completed a preliminary analysis this fall. The analysis found evidence of success for some students under RISE, but not all.

To better understand both the benefits and challenges of RISE, we interviewed dozens of faculty, administrators, and students at community colleges across the state. As the pandemic continues to wreak havoc on education systems, getting remedial education right has never been more important.

What’s working

Reforming developmental education is more than just overhauling an existing structure. Conceptually, it’s about “connecting students who would otherwise be on the margins of the economy and society and connecting them to opportunity. We’re trying to activate talent … that’s the big picture,” said Josh Wyner, executive director of the College Excellence Program at the Aspen Institute.

And that’s what RISE is doing — expanding access to gateway courses, which are a student’s first college-level courses that are credit-bearing and are requirements for associate degree programs.

“Students who would have never gotten to entry-level math or English pre-RISE are now making it. Expediting the process helped create the access, but also [gave students] the motivation to continue,” said Jonathan Loss, associate dean of general education at CVCC. Randy Ledford, vice president of instruction at Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute, and Mark Poarch, the president, agree. “The data is clear — RISE is increasing access to gateway courses,” Ledford declared.

The system’s preliminary analysis confirms what Garrett Hinshaw, Loss, Ledford, and Poarch are seeing at their colleges. The analysis compares student outcomes at colleges that piloted RISE in spring or fall 2019 to the same outcomes at colleges that did not implement RISE by fall 2019. For each group, the system office looked at student outcomes from the fall 2018 semester (before RISE) to the fall 2019 semester (with RISE at pilot colleges).

The analysis finds that students with a GPA between 2.2 and 2.79, which means they qualified for a corequisite class under RISE, completed both college-level math and English in their first semester and first year at higher rates in fall 2019 than in fall 2018 at RISE pilot schools. Non-pilot schools saw a decline in first semester college-level math completions and no change in first semester college-level English completions and first year college-level math and English completions in that same group of students.

“The data shows that for students in that range of 2.2 to 2.79, so students that would in the past have most likely gone into developmental education and now are being offered the opportunity to take a credit-bearing course with a coreq, they’re seeing good successes,” said Susan Barbitta, executive director of student success at the community college system.

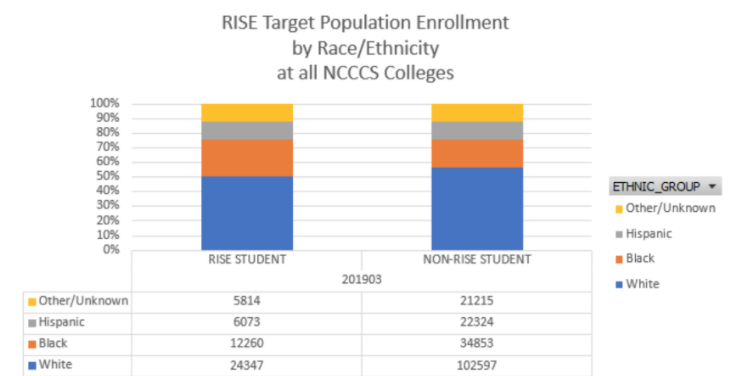

In addition, Loss said they are seeing that “RISE continues to shrink equity gaps.” Preliminary data shows that the students enrolling in college-level courses with a corequisite through RISE are more likely to be students of color and students who qualify for Pell grants.

Another major plus is the reduction in the number of placement tests given. “Those tests are very long and very hard. To ask a new student to take a three-hour test, multiple ones, that’s quite a challenge and quite daunting to someone who’s never been in college,” said Beverly Watts, director of developmental studies and quality enhancement at McDowell Technical Community College.

Furthermore, previous research from the Community College Research Center (CCRC) found that placement tests are not always accurate. In 2010, CCRC found that the national placement tests North Carolina had been using misplaced on average three out of 10 students into developmental education.

In addition to expanding access, decreasing equity gaps, and reducing placement tests, student support has also been bolstered by RISE. The corequisite course structure gives faculty members an opportunity to address issues with gateway course content almost immediately.

As LaRonda Lowery, assistant vice president of university transfer and health sciences at Robeson Community College, explained, “When I taught [corequisite] courses, you knew the students that needed extra support. Since those courses were typically lower enrollment courses, I could figure out where they were struggling and provide that one-on-one support.”

And the support works, according to students and faculty. John Bowman, English department head at Stanly Community College said, “Students in my ENG 111 class who also have the corequisite class hand in better papers. They get a little bit of extra practice. It helps them do better in the gateway course.”

“I think I did more learning in the support [corequisite] class than I did in the actual [gateway] class,” said Cassi Tong, a student at CVCC. “There was a lady in class with me, and we developed a sisterhood over this math issue. She and I helped each other learn. We got a lot out of that class, and we both raved about how much help was provided [by the instructor].”

For Luis Millan-Lara, another CVCC student, the corequisite allows students to identify what they’re struggling with and get help. “We get to write what we need help with. Many students probably don’t feel comfortable speaking in class or they have a hard time saying that they are having a hard time understanding, so this is a good way for [the instructor] to get insight from those students and understand which way she needs to go.”

Despite these positive results, students, faculty, and administrators have also experienced challenges with the new model.

The challenges of RISE

“I think one of the things about change and transformation is you have to take a risk,” said Mary Rittling, former president of Davidson County Community College. “You can’t just say ‘I can’t do this.’ You have to figure out a way to do something — sometimes you have to circumvent the system to figure out what’s best for students.”

But change is hard. And no matter how much planning or research goes into a restructure, there will always be bumps in the road. From scheduling to staffing issues to GPA cut-offs and hours spent in corequisite classes, these are the types of challenges that faculty and administrators identified in our interviews.

In the beginning, RISE required students to be enrolled in the corequisite course that corresponded to their gateway class. For instance, if a student enrolled in the gateway math course MAT 152, statistical methods, they would also be placed in the corequisite class, MAT 052. Many colleges told us they struggled to enroll enough students in each of the corequisite sections.

A MAT 052 corequisite could have two students in it, and the MAT 071 corequisite may only have four students enrolled. And since best practices recommended that corequisites be taught face-to-face, it was even more of a challenge. To mitigate scheduling issues, Poarch noted, “We took our concerns back to the system office, and they made a change to their requirements.”

Institutions are not the only ones with scheduling issues. In a previous article, we discussed the amount of class time required for the gateway class and the corequisite. A student enrolled in MAT 171, for example, will have five hours of class time each week. If they require the corequisite, MAT 071, they will have an additional four hours of class time per week.

Trying to schedule other classes — and jobs and family responsibilities — around gateway and corequisite courses can pose problems for students. “You have to start thinking about teaching those [corequisites] online or even hybrid, and then you have your most vulnerable students in a setting that may not work for them,” said Poarch.

And it’s not just schedule conflicts. The amount of time students spend in gateway and corequisite courses can be burdensome. “If you’re in a gateway math class that meets three days a week, and in a corequisite that meets two days a week, you’re in math all week. For some students, that just feels like a lot of math,” said Kim Gold, senior vice president and chief academic officer at the community college system office.

RISE also comes with a learning curve. Advisors have to be trained on how to place students in the right courses, and faculty need professional development on best practices in teaching corequisite and transition classes.

“We’re all learning the program platform, learning how it works, and just figuring it all out. That’s been a challenge — the layout of the course,” said Watts. Because there are multiple ways to place students in classes, Watts told us, “I’m still getting calls from faculty asking if they placed a student correctly.”

For the most part, the more technical requirements were the only reason faculty and administrators had challenges with the corequisite courses. The transition courses are a different story, however.

The system’s data analysis shows that students with a GPA less than 2.2, which means they were placed in transition courses under RISE, completed college-level math and English in their first semester and first year at lower rates in fall 2019 than in fall 2018 at RISE pilot schools. At non-pilot schools, however, completion rates for the same group increased from fall 2018 to fall 2019.

The fact that first semester completion rates of college-level math and English declined for these students when schools implemented RISE is expected — these students were placed in transition courses instead of having the chance to take a placement test and place into college-level courses their first semester. However, first year completion of college-level math and English also declined for these students at RISE schools while both increased at non-RISE schools.

“The area that is having us look a little more closely are those students that are coming in with an unweighted high school GPA below 2.2, because those students right now are being sent to a one-semester transition course, and, again [this is] one semester’s worth of data, but they don’t seem to be faring as well as we had hoped they would,” Barbitta said.

Mark Sorrells, senior vice president of academic and student services at Fayetteville Technical Community College, said they are losing students who are not successful in the transition courses. “The place where we are losing more students is if they get into those transition courses and they’re not successful –chances are they’re not back in the enrollment next semester,” said Sorrells.

Students in the transition courses use self-paced online software by a nonprofit organization called NROC. Instead of learning together in class, students log onto the platform and complete math and English lessons online at their own pace. Some faculty members said they struggle with this model and do not like the software.

“The instructors had more control over [the software we were using before RISE]. We have no control over [NROC]. We can’t do anything with it,” said Joyce Lewis, a math faculty member at Fayetteville Tech.

Faculty members at McDowell Technical Community College agreed. “When [students] practice, they are given the same problem over and over again. Because there are a lot of multiple choice questions, students can essentially derive what the answer will be,” said Watts.

Some faculty members said the self-paced online software allows them more time to give one-on-one help to their students, but more seemed to struggle and did not know how to support students. “With the new platform, there’s just not that flexibility nor the depth or breadth of examples available to [faculty]. It really is becoming dependent upon the instructors to supplement what is going on,” Watts said.

Ahrash Bissell, president of NROC, said the platform is not meant to be used by itself but rather to support teachers in differentiating instruction to students. “The technology reveals the information that allows you to target instruction in a much more effective way,” Bissell said. “And that’s why we say it is, in effect, a differentiation support tool.”

Perhaps most challenging to RISE implementation is changing mindsets. “People don’t object to change because they don’t get the analytics part of it,” Wyner said. “They get attached to doing things in the old way, and they identify with that as part of their identity.”

Shifting mindsets is hard work, and leaders must be trained in change management, Wyner said. Nikki Edgecombe, senior research scholar at Community College Research Center, explained, “When reforms affect the classroom, they tend to generate a bit of pushback because faculty aren’t used to being told how their practice needs to be changed.”

Colleges that have seen success credit buy-in and a clear vision from leadership. “It takes leadership — leadership and keeping on track with vision and purpose about why we’re doing this,” said Loss. “We’re not doing this because the system office told us we have to do this. We’re doing it because it’s the right thing to do.”

Garrett Hinshaw, president of Catawba Valley Community College, said colleges must be strategic in planning, figuring out who will be the champions among staff and leadership, and listening to faculty throughout the process.

“Change is hard,” Hinshaw said. “[Presidents] really need to take time to identify the key people on the campus that will be planning, implementing, and launching this program and take the time to build those relationships. Listen to people. Listen to what they’re seeing in the classroom.”

In the next article of the series, we will look at how one college has transformed the way they do developmental education by focusing on an essential ingredient for student success — making students feel like they belong and building their confidence.

Behind the Story

Molly Osborne and Emily Thomas reported and wrote this series. Analisa Sorrells, Eric Frederick, and Mebane Rash edited it.

Over the course of four months, we interviewed five North Carolina Community College system office staff, 10 former or current community college presidents, 18 community college administrators, 14 faculty members, 14 students, one Department of Public Instruction administrator, and nine community college researchers and national experts.

Recommended reading