This is part of a series on developmental education in North Carolina. Click here to read the rest of the series.

Jonathan Loss has worked in the North Carolina community college system for 16 years. At Catawba Valley Community College (CVCC), he started as a faculty member in the math department, then became department head, and is now the associate dean for general education. He has experienced firsthand the remedial education reforms of the past 10 years.

Remedial or developmental education courses are designed for students who aren’t prepared for college-level math and English classes. Over the past decade, North Carolina has overhauled its developmental education system after data showed too many students were getting stuck in developmental classes and dropping out.

“We had problems with students staying forever,” Loss said, talking about developmental education when he first started as a math faculty member. “Those courses were a semester long, each of them. You could take four semesters of remedial math before you ever got to a college-level math course.”

In 2013-14, the community college system switched to shorter module courses that were supposed to allow students to complete their developmental coursework in two semesters rather than four. That helped some, Loss said, but not enough.

“Even though it was possible to do this in two semesters, the actual reality was that very few students were doing that,” Loss said. “They’d spin their wheels, get frustrated, and drop out.”

A few years later, Loss and his colleagues at CVCC saw the data on a new developmental education model that other states had adopted. “The numbers were staggering and in many ways almost unbelievable,” Loss said. “If it works in Georgia, Tennessee, Florida, why could this not work in North Carolina?”

When the North Carolina community college system asked for volunteers to pilot this new model, CVCC jumped at the chance. Starting in spring 2019, they joined 13 other colleges across the state and piloted a new corequisite model of developmental education called RISE, which stands for Reinforced Instruction for Student Excellence.

The nuts and bolts of RISE

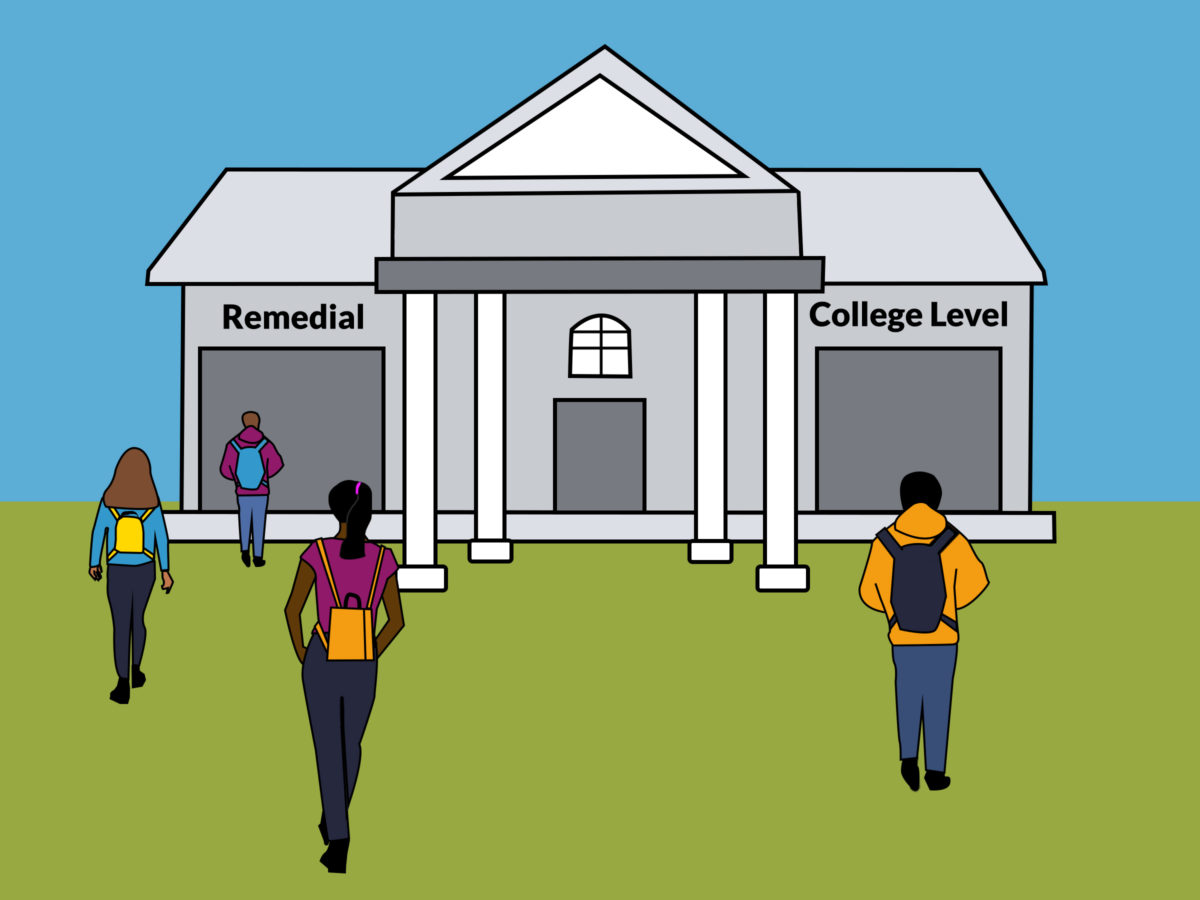

Corequisite models prioritize getting students enrolled in what are called “gateway” math and English courses as soon as possible. These are a student’s first college-level courses that are credit-bearing and are requirements for associate degree programs. The idea is that students are more likely to stay enrolled and succeed in these foundational classes if they can start taking them immediately and receive support at the same time.

Previously, if a student was deemed unprepared to take college-level classes, they were enrolled in prerequisite developmental math and English courses. When colleges made the switch to RISE, they got rid of these and created corequisite and transition courses instead.

Using a series of criteria, known as “multiple measures,” colleges place students into one of three pathways:

- Gateway math and English courses

- Gateway math and English courses with a corequisite course

- Transition math and English courses

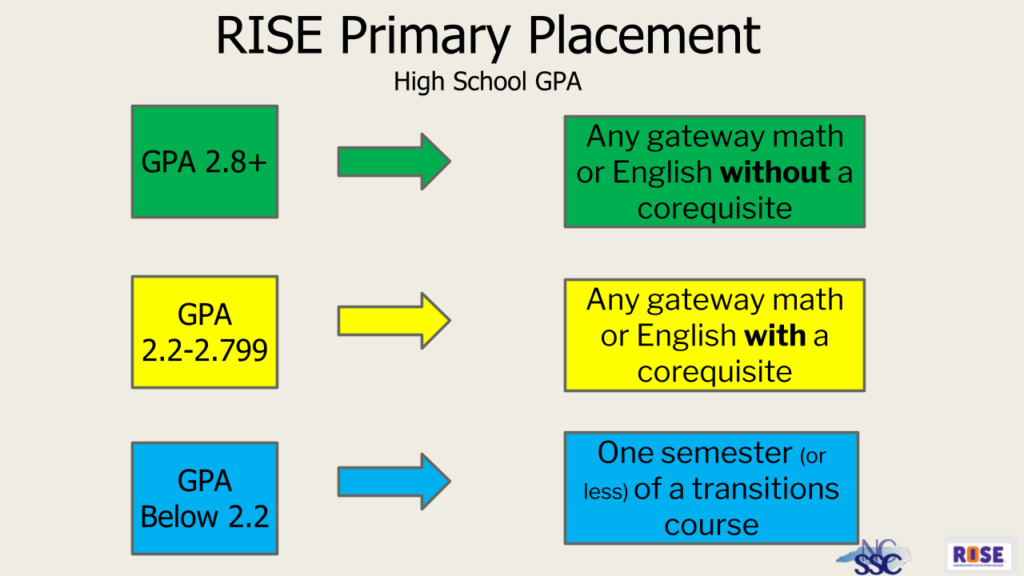

If a student has graduated high school within the past 10 years, the student’s unweighted high school GPA will determine placement. The chart below indicates benchmarks for placement.

If students do not want to use their high school GPA, or don’t have one, they can also use the following measures to place into college-level courses.

- ACT/SAT scores

- GED/HiSet scores

- Associate/Bachelor’s degree

- AP/IB Scores

- Transfer credit

Students who do not meet any of the measures above or graduated from high school more than 10 years ago take a placement test. Since COVID-19, colleges have dropped the 10-year rule and are accepting any high school GPA.

Students who meet the requirements to enter gateway math or English courses without a corequisite may select the appropriate college-level math and English courses for their chosen program. If a corequisite course is required, students are placed in the appropriate corequisite course that provides contextualized support in their gateway math and English courses.

And while the corequisite model’s goal is to expedite students’ entry into college gateway courses, there are still some students who need extra support. If a student is deemed unprepared for gateway math or English courses even with a corequisite, the student is registered for a transition course. Transition courses provide foundational English and math content and help students develop learning strategies that will allow them to be successful in college-level classes. Let’s take a closer look at each of these options.

The corequisite course

Jacob Witke, a student at CVCC, started his college journey in fall 2019. As a homeschool graduate, Witke did not have a high school GPA that could be used for placement. Instead, CVCC used his SAT scores. Although Witke loves numbers, his scores did not quite meet the threshold for college-level math courses.

In fall 2020, Witke enrolled in MAT 171, which is precalculus algebra, along with the corequisite MAT 071. While he enjoys MAT 171, he says it’s the corequisite course that is one of his favorites.

“In the coreq, we talk about math, but we also talk about what we are struggling with, and [the instructor] gets to know us as students. It’s a chance for students to say, ‘Hey, this is what I’m struggling with. Can we discuss this?’ Because in the other class, where she’s lecturing, we don’t do that as much, but in this class we have more opportunities to go over what we are struggling with and overcome that.”

And talking about struggles outside of math is what Witke appreciates most. He said, “That’s the beauty of this class. We discuss things like mental health. We talk about other stuff, personal life … We have a weekly assessment that the professor does. Reflect on your week. What went good? What went bad? It’s one of the best parts of the class.”

The reflection that Witke described is part of the growth mindset principles embedded in each corequisite course. According to this definition, “In a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work — brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Beyond growth mindset activities, corequisite courses help students develop skills like time management, writing a professional email, note taking, test preparation, and more.

Depending on the gateway course, students will have between two to four hours of class time per week in the corresponding corequisite. For example, a student taking the gateway course MAT 143, quantitative literacy, and the corequisite MAT 043, will have four hours per week of class time in MAT 143 and three hours of class time per week in MAT 043. By contrast, a student enrolled in MAT 171, precalculus algebra, and MAT 071, will spend five hours per week in MAT 171 and four hours per week in MAT 071.

According to RISE best practices, the same faculty member should teach both the gateway course and the corequisite. Best practices also recommend a corequisite be taught in the same manner — online, hybrid, or in-person — as the gateway course. While scheduling does not always allow this, research suggests that corequisites are best implemented when they are taught immediately following a gateway course.

Students earn grades of either Pass (P) or Fail (F) in the corequisite course. If a student passes the corequisite course but fails their gateway course, they must retake both courses. However, if a student fails the corequisite but passes the gateway course, many colleges allow the student to progress without retaking the corequisite course.

The transition course

Cassi Tong grew up right outside San Antonio, Texas and graduated high school in 2010 with the minimum requirements necessary. “I had a heck of a time throughout my childhood with math,” Tong said. “I was in special ed math throughout my entire schooling, and it was really, really rough.”

Tong and her husband moved to North Carolina in 2015. “The only opportunities I had were fast food jobs and minimum wage jobs,” she said. “So with no further educational background, I wanted to go back to school.”

Tong enrolled at CVCC to get an associate degree in medical office administration and was placed in the transition math course. “I went into it really nervous and really pessimistic,” she said. “I thought it was going to be really stressful. I thought for sure I was going to have the hardest time because math has always been my sore spot.”

But what happened during the class surprised her. “I had a lot more confidence in what I was doing,” she said. “I really appreciated how they were teaching. If I had a teacher like Ms. Hayes and Ms. Campbell when I was growing up, I would have been in a lot better situation.”

When colleges made the transition to RISE, they moved to an online software platform called NROC. Students who are placed in the transition courses take a diagnostic exam through NROC, which tells them where they need to start. They then progress through online tutorials, videos, and practice problems at their own pace. When they have completed the practice, they take a test to demonstrate mastery of that unit.

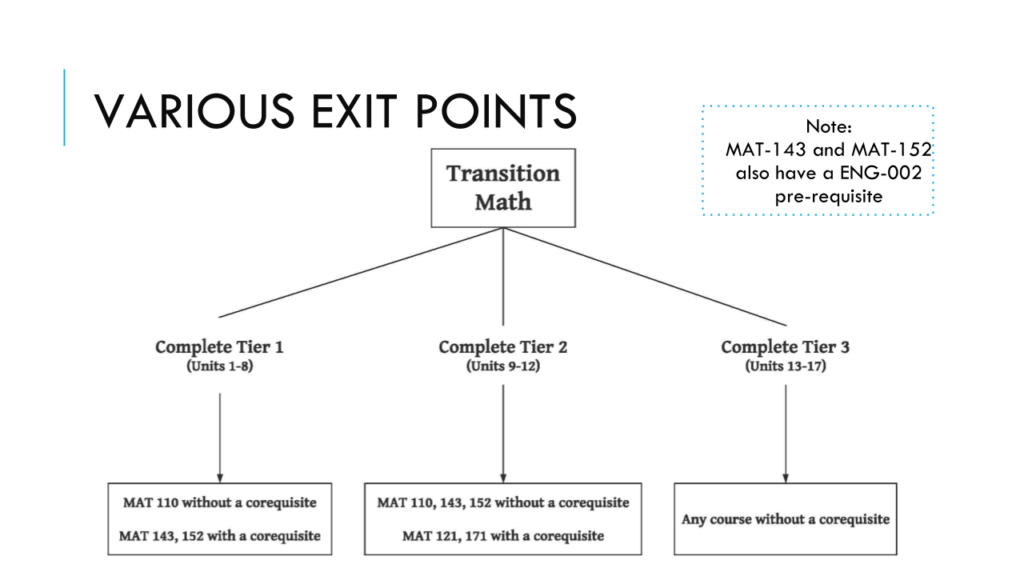

Students in the math transition course use an NROC program called EdReady that has 17 units. The course is broken up into three tiers with various exit points to finish the course. If a student completes tier I, he or she can enroll in MAT 110 without a corequisite, but can only enroll in MAT 143 or MAT 152 with a corequisite. If a student completes tier 2, he or she is eligible to enroll in MAT 143, MAT 152, or MAT 110 without a corequisite. Only when a student completes tier 3 can he or she enroll in any math course without a corequisite.

The transition English course is also run through NROC and contains 10 units. Transition English is broken up into two tiers also with various exit points. Students can complete tier 1 and move on to gateway ENG 111 with a corequisite. If the student completes tier 2, he or she is eligible to enroll in ENG 111 without the corresponding corequisite course.

Like corequisite courses, students receive a Pass (P) or Fail (F) in transition courses. Transition courses also offer growth mindset principles. However, while corequisite courses are taught by a faculty member, students in transition courses use the NROC software program primarily and reach out for faculty support when they need it.

CVCC’s experience so far

Loss said the switch to RISE has been positive for CVCC students. “I’m a big believer in the change,” he said, adding that “it’s still not perfect.”

“The biggest win for me in RISE so far that we have witnessed is the access that it’s creating,” Loss said. “Since spring 2019, we’ve had several hundred students who have passed English 111 who never would have had the opportunity to even take English 111.”

“We’ve definitely increased the number of students that have moved on to the next level of study in their curriculum,” CVCC President Garrett Hinshaw said. “And that really helps them in terms of their confidence and also their progression.”

Loss shared their data with us when we visited CVCC in November 2020. He compared the number and passage rates of students in gateway math and English classes from spring 2019 to summer 2020 with the number and passage rates of students in those same classes from spring 2017 to summer 2018.

Since they implemented RISE, CVCC has seen 399 more students taking college-level math and English courses than in the same time period previously, an increase of about 9%.

The pass rate of students taking gateway math and English courses has remained virtually unchanged since CVCC implemented RISE. From spring 2017 to summer 2018, 69.7% of students passed these courses compared to 69.6% from spring 2019 to summer 2020.

Loss disaggregated the data by looking at the pass rates for students who were enrolled in a corequisite compared to those just taking the gateway course. In all but one math course, the pass rates of RISE students were lower than non-RISE students, but not by much.

“I would expect it to be lower,” Loss said, “because their GPA is showing they’re not as strong of a student, so I wouldn’t expect them to necessarily pass at the same rate. The hope would be that the [corequisite course] enables them to perform at the same level, but there’s going to be some difference.”

The next step in understanding their data, Loss said, is disaggregating it based on race and ethnicity to see if there are substantial gaps.

Hitting pause

Not all colleges are as positive about RISE as CVCC. In fact, the North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents voted to delay the system-wide roll out of RISE until spring 2022, a decision that came as colleges faced the disruption of COVID-19.

According to Amanda Lee, president of Bladen Community College and the head of the programs committee that made the recommendation to delay, it came down to understanding whether or not RISE was actually working.

“Developmental education is a complex topic,” Lee said. “I’ve been in higher education for a long time, and we’ve always grappled with how do we get students ready for their college-level work whether they’re fresh out of high school or they’re returning and need some refreshing before they jump in.”

“The problem with RISE in particular,” she continued, “is that we had done a pilot and we were having trouble getting the data together to really assess it to ensure that we were going in the right direction before we did a statewide implementation.”

Despite the pause, 55 of the 58 community colleges have implemented some form of RISE as of fall 2020, according to a fall 2020 system office survey. In the next article of this series, we’ll take a look at what’s working with RISE, what’s not, and what the first statewide data analysis of RISE tells us.

Behind the Story

Molly Osborne and Emily Thomas reported and wrote this series. Analisa Sorrells, Eric Frederick, and Mebane Rash edited it.

Over the course of four months, we interviewed five North Carolina Community College system office staff, 10 former or current community college presidents, 18 community college administrators, 14 faculty members, 14 students, one Department of Public Instruction administrator, and nine community college researchers and national experts.