The State Board of Education Literacy Task Force is zeroing in on its final recommendations for how reading instruction should change throughout the state. The task force met Thursday and focused on the choice of specific words in its recommendations, and their ability to lead to that change.

The group will vote in the coming days to finalize its recommendations, which will be presented to the State Board at its June 3 meeting. The task force has been working since December on suggested changes to teacher preparation, curricular materials, and professional development to “support the improvement of K-3 reading instruction.”

In 2018-19, 57% of North Carolina third-graders scored proficiently on end-of-grade reading tests. (Go here to see the proficiency rates by district.) State leaders hope to increase that rate, which has held steady in recent years despite the state’s Read to Achieve legislation and millions of dollars in funding aimed at improving proficiency.

The task force’s recommendations — which are still in draft form and will be updated before a final vote to reflect Thursday’s meeting discussions and edits — are below. Go here to listen to the entire meeting.

The recommendations include embedding literacy coaches in elementary schools to support teachers, requiring additional literacy professional development for teacher and principal licensure renewal, limiting state funding to support only science-based curricular materials, and ensuring that educator preparation programs provide coursework and clinical experiences that equip teachers with an adequate understanding of how students learn to read.

Related reading

A definition to ground the work

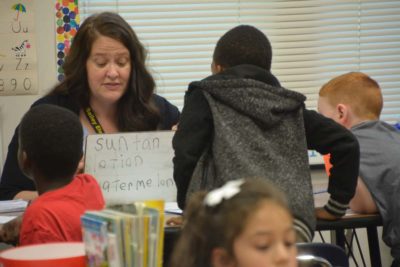

Members grappled Thursday with details of exactly what high-quality reading instruction entails — continuing a discussion that has spanned the task force’s months of work. Kristin Gehsmann, a task force member and chair of literacy studies, English education, and history education at East Carolina University, recommended that the word “motivation” be inserted between “world knowledge” and “comprehension” in the following definition that precedes the task force’s recommendations:

High quality reading instruction is grounded in the current science of reading regarding the acquisition of language (syntax, semantics, morphology, and pragmatics), phonological and phonemic awareness, accurate and efficient word identification and spelling, world knowledge, and comprehension. It is guided by state-adopted standards and informed by data so that instruction can be differentiated to meet the needs of individual students. High quality reading instruction includes explicit and systematic phonics instruction, allowing all students to master letter–sound relations so that they can understand the meaning of increasingly complex text.

“The effect size of motivation in the area of reading is quite strong,” Gehsmann said, pointing to the work of researcher John Guthrie.

Barbara Foorman, a national literacy expert and consultant to the task force, suggested a separate sentence or footnote be added that mentions motivation.

“It’s not like a separate domain that you need to master to become a reader,” Foorman said. “It’s really part of the instructional context — so that it’s not that you have a reader who is motivated or not. It’s that a reader is in a context where there are motivational forces at play.”

Gehsmann also suggested the words “valid and reliable assessment” be added when describing the data that should inform instruction, with the intent of “emphasizing the importance of assessments tools that have psychometric properties that lead us to… have some confidence in the data, which has not always been the case.”

In a later discussion about a recommendation that aligns diagnostic and statewide assessments to scientific research, Gehsmann again stressed the importance of assessment choice and alignment: “What we know about school change is that what is assessed is taught.”

How to ensure science-based curricula

Members discussed the degree to which the state should influence districts’ decisions on what materials they use to teach students to read.

The following recommendation suggests the state define criteria for evidence-based materials and create a rubric to help districts make informed decisions.

Define criteria for evidence-based resources aligned to the current science of reading. Create a state-level rubric utilizing expert literacy stakeholders (i.e. teachers, school leaders, district leaders, North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) representatives, IHE partners, etc.) to review, vet, and determine alignment of K-5 literacy core, supplemental, and intensive materials aligned to the current science of reading.

But Melba Spooner, task force member and dean of Appalachian State University’s College of Education, said she does not think the recommendation does enough to help districts and ensure the selection of high-quality materials.

“I believe the intent of our committee when we worked on this was to lift the burden off … public school units to make the identification of high-quality instructional materials aligned to the current science of reading easy to select or easy to identify,” Spooner said. “I don’t believe that we’ve ended up with a recommendation that necessarily does that.”

Throughout the group’s work, the idea of the state creating a specific list of science-based materials has arisen —and some members have cautioned against it because of variations in districts’ needs and resources, as well as potential legal issues with vendors that are excluded.

“They become very time-stamped,” Gehsmann said regarding lists with specific materials. She suggested the idea of the State Board making evaluation data on different materials available to districts.

Vickie Sutton, task force member and Greene County’s K-5 literacy coordinator, expressed concern with another recommendation around this same issue:

“Allocate funding for only evidence-based core, supplemental, and intensive instructional materials aligned to the current science of reading for every K-5 student. Every student needs access to high quality curricula.”

“I get what we’re going for is we want the LEAs to choose wisely and to choose the materials that support this new paradigm shift, but I don’t like the word ‘only,'” Sutton said.

Other members, like Kimberly Vaught, task force member and principal of Lawrence Orr Elementary in Charlotte, said direct language is needed for change at the classroom level.

“I get that we want to make sure people feel flexibility and autonomy, but certainly, as a school principal, having worked in different dynamics, I definitely think we need to move forward with the word ‘only’ to be able to provide teeth and support for school districts — and at the state level — for enforcing what we know to be best practice and the recommendations that we’re putting our names behind,” Vaught said.

Ann Clark, task force co-chair and former Charlotte-Mecklenburg superintendent, echoed Vaught’s sentiment: that the task force’s purpose is to ensure high-quality instruction.

“I just want to make sure we understand the intent here is around state funding and that if we take the word ‘only’ out, we are opening up the opportunity for districts to use state dollars to invest in curriculum… that is not aligned to the current science of reading,” Clark said. “So I just want to make sure that we have our eyes wide open … Our purpose is to have 100% of our districts using core, supplemental, and intervention materials that are aligned.”

Recommended reading