A group of education leaders and experts met for the first time Friday to decide how to better prepare teachers on instructing young children how to read.

With reading proficiency scores lagging and the multi-million dollar Read to Achieve investment showing null results, the state is asking how to do things differently. The PreK-12 Literacy Instruction and Teacher Preparation Task Force will report to the State Board of Education in March with recommendations on how the state should tweak teacher licensure requirements, summer reading camps, professional development opportunities, and educator preparation programs through coursework and clinical experience.

“I know that 90 to 95% of our kids can … learn to read, and we only have 56% who are showing proficient on tests,” said Tara Galloway, the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) K-3 literacy director. “So we have to find ways to help these kids over these hurdles.”

A 2018 review of the UNC system found educator preparation programs don’t give teachers enough training in evidence-based reading instruction, with practices varying widely across programs and some assignments appearing “irrelevant to teaching literacy, or at least not inclusive of research-based practices.” Once they’re in the classroom, the majority of districts use curricula based on “balanced literacy” approaches instead of strategies based on what research says is most effective.

Both improving the preparation of reading teachers and the practice of literacy instruction in districts will be critical for making a difference in students’ proficiency, said Ann Clark, chair of the task force and former Charlotte-Mecklenburg superintendent.

“I think that is potentially one of our largest equity opportunities is to come together as a state, quite frankly, and agree on an evidence base, and agree on it not just on the [educator preparation program] side but on the preK-12 side, because if there’s this great preparation that’s happening and then teacher candidates are going into schools that are using a variety of different approaches to teach reading that are not evidence-based, we haven’t truly advanced the ball,” Clark said.

Can science knock down barriers to reading proficiency and rescue Read to Achieve?

The task force is charged with examining how many credit hours related to literacy should be required for soon-to-be teachers — and whether phonics instruction is integrated enough into current courses or if a separate class focused on phonics should be added. The group will dive into the clinical experiences, or hands-on classroom experiences, that students are exposed to while in school, and how they do or do not include effective literacy instruction.

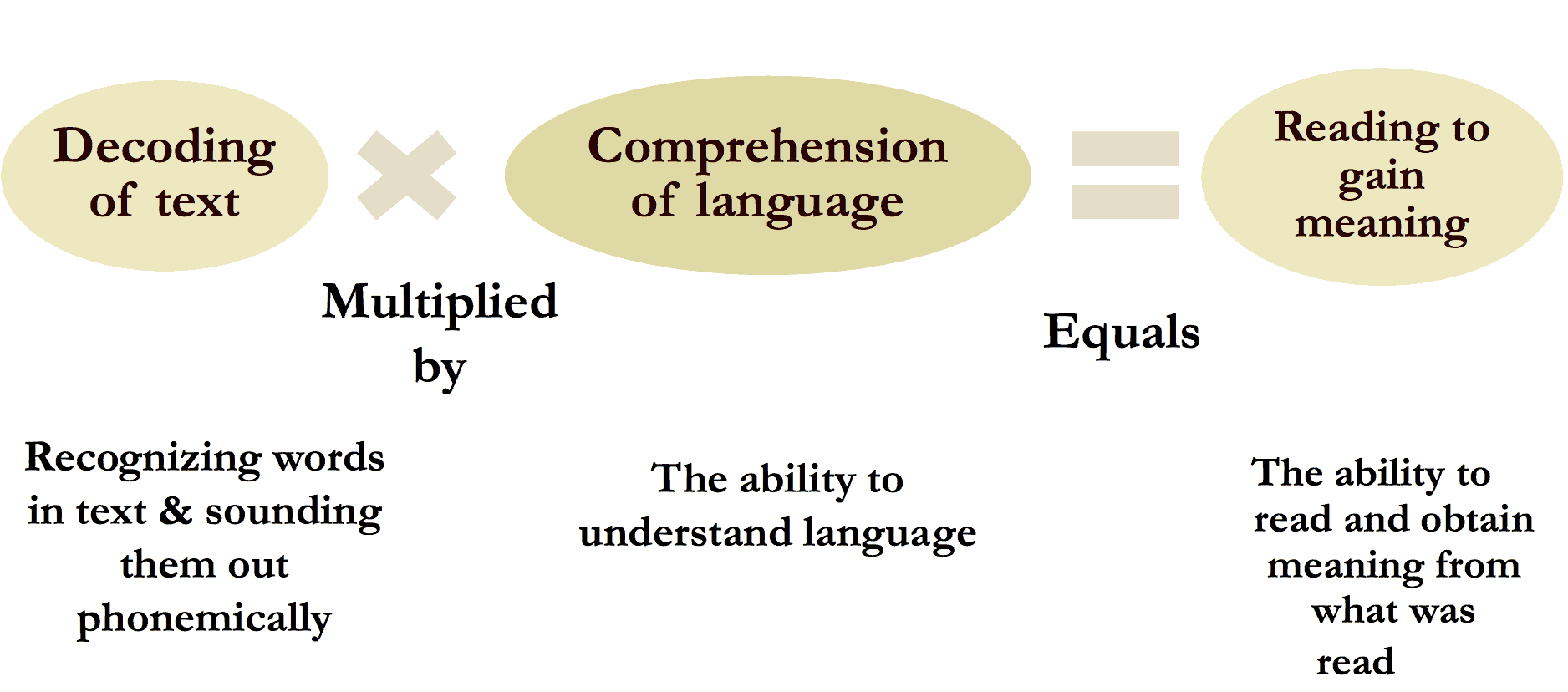

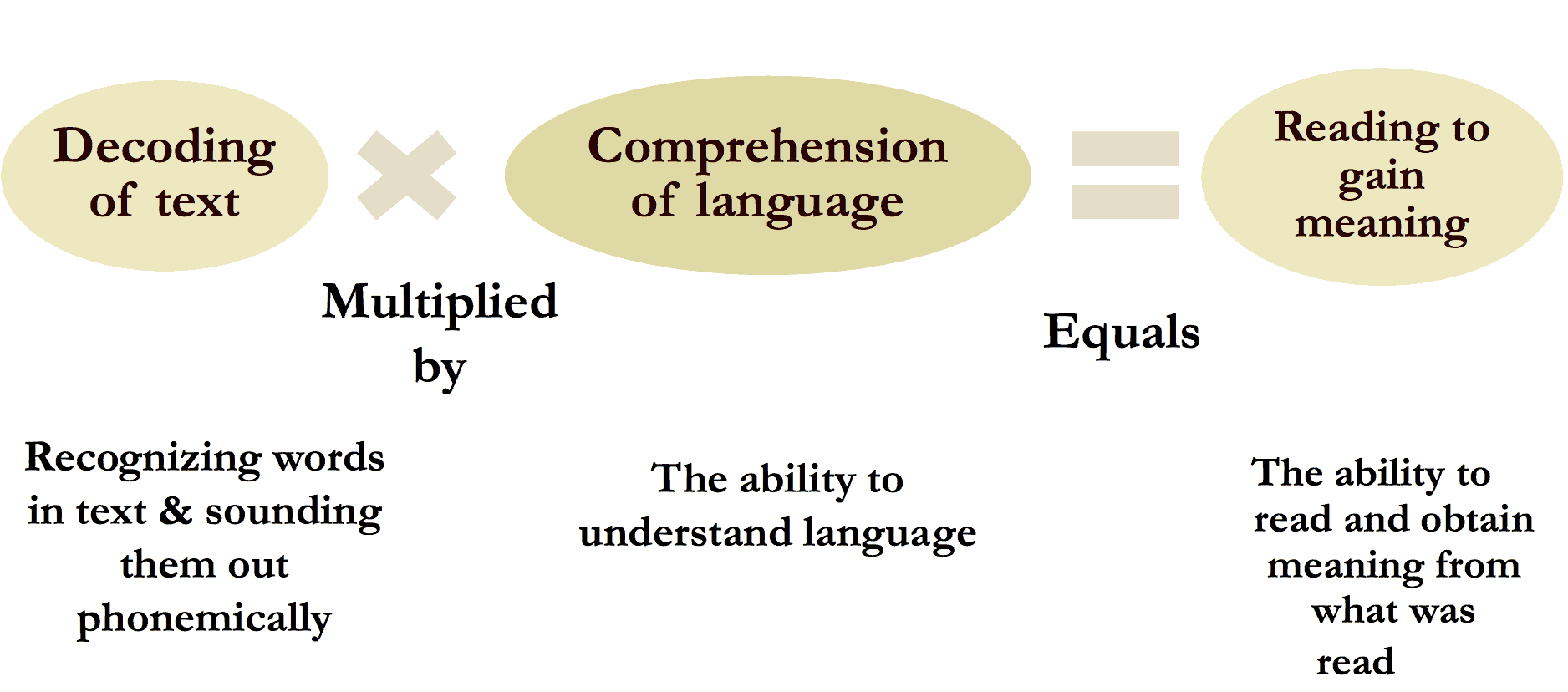

Laurie Lee, the Improving Literacy Research Alliance Manager for the Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast at Florida State University, said preparation programs that prepare effective educators give a deep and broad knowledge base of literacy components. Putting it simply, children learn to read through the decoding of words and comprehension of language.

This instruction should be explicit and strategic to the student’s needs, Lee said. Assuming children will pick up reading comprehension without learning specific skills on how to do so will not produce results for many readers.

“Our kids learn to talk because our kids hear what they hear,” Lee said. “They don’t learn to read unless we teach them. Reading is not an innate process like acquiring language is.”

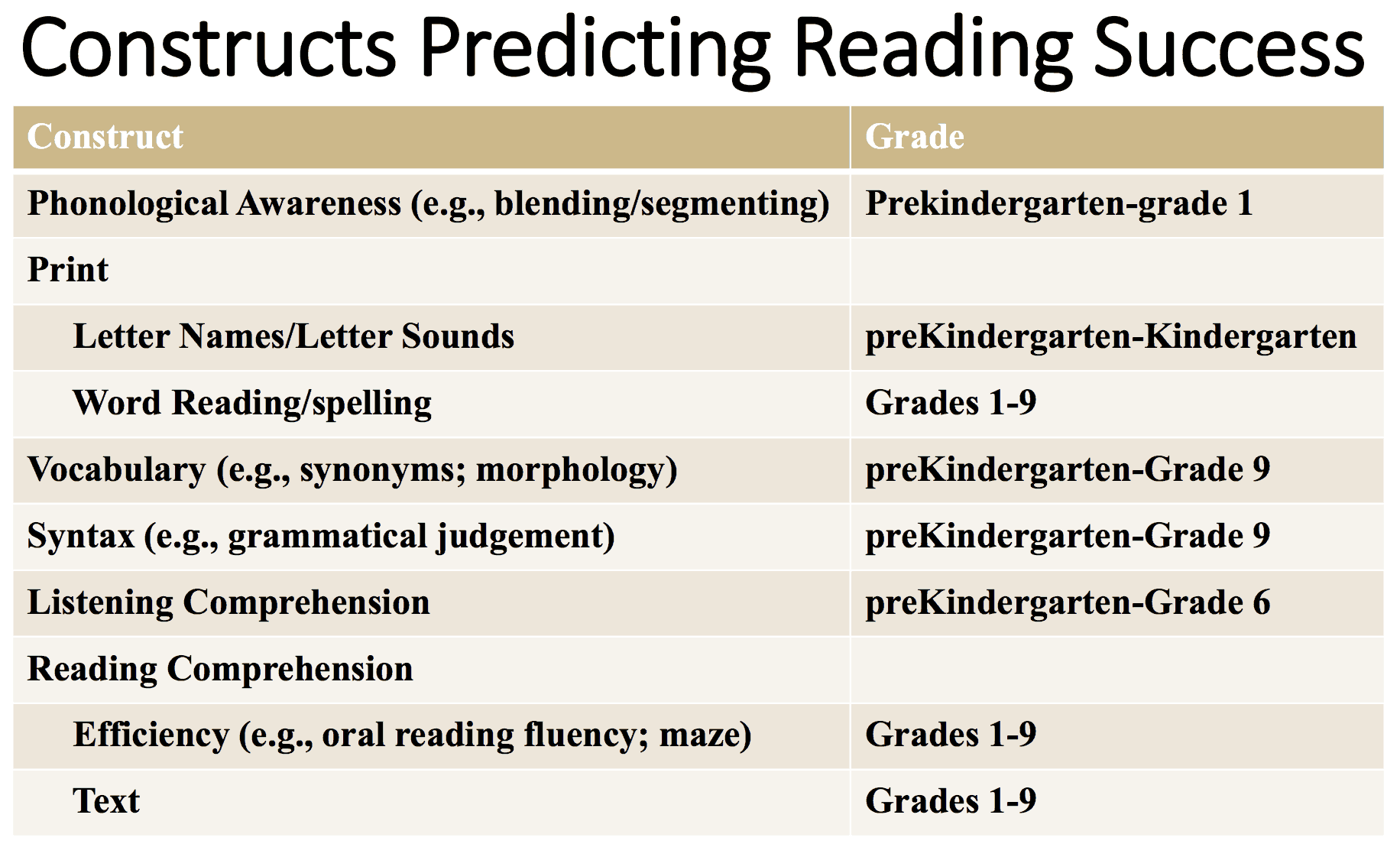

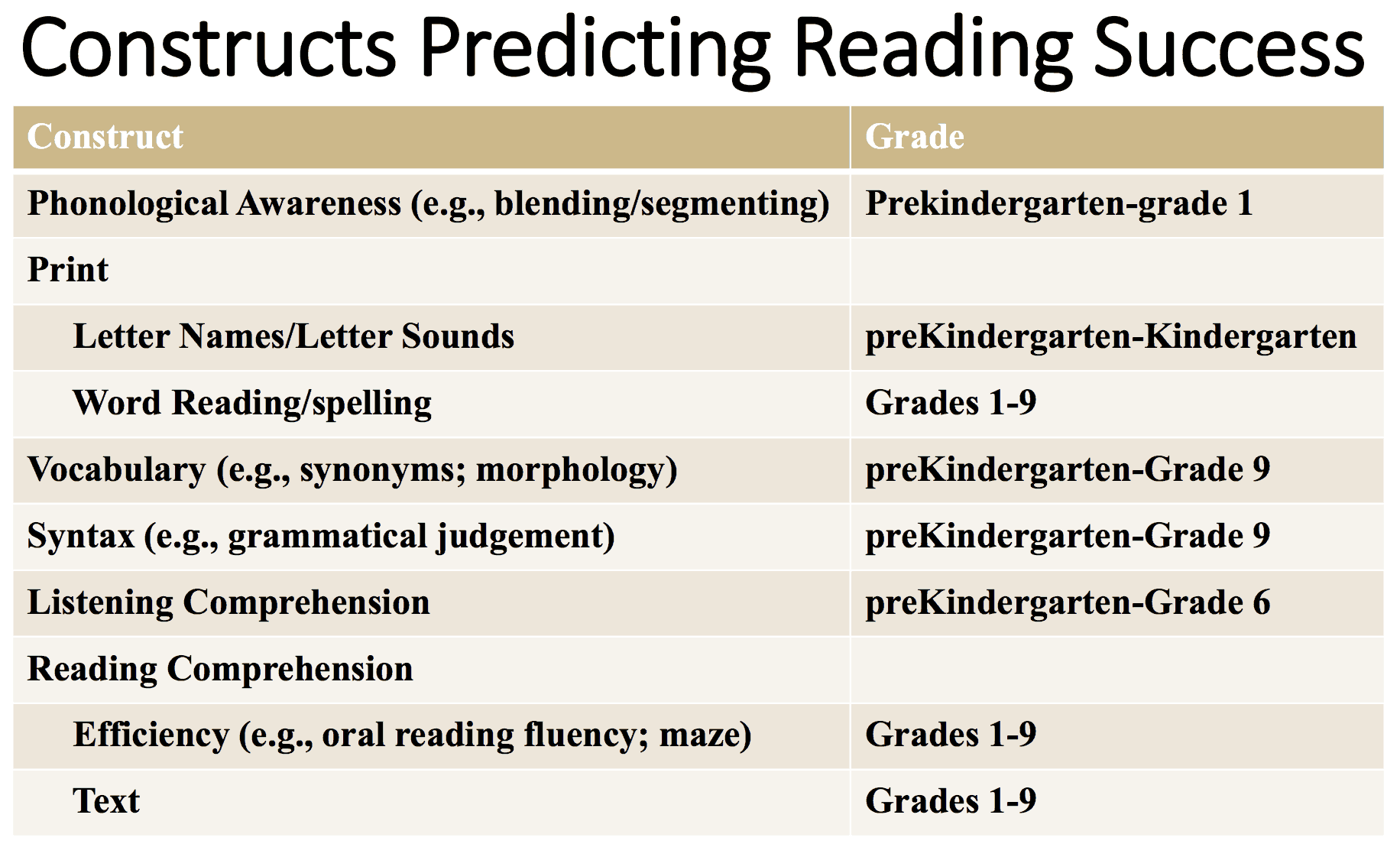

As students move through different grades and literacy competencies, they need different interventions and different emphases on certain literacy components. The following table lays out which constructs children should be exposed to as they move through the education system.

Effective educator preparation programs, Lee said, create courses that move through these literacy components in a way that builds consecutively and includes knowledge of literacies in diverse communities.

Just knowing this content is not the same as being able to teach it to a class of 20 or more learners who are all at different reading levels. Lee said teacher candidates should have consistent and high-quality field experiences where they can learn to apply that knowledge. These clinical experiences, including a year internship at the end of their programs, should include guidance by mentors and engagement with diverse students and families.

The task force also will look at the state’s teacher licensure system, considering whether compensation or other incentives could motivate teachers’ literacy instruction knowledge and skills. While teachers renew their licenses every five years, the group will evaluate whether that process could include continuing education credits related to literacy. The task force will discuss ideas for professional learning opportunities for teachers to stay up to date on the latest literacy research throughout their careers. The group also will look at principal preparation programs and professional development ideas for elementary school principals to support effective literacy instruction.

The UNC Teacher Preparation Advisory Group — the same body that released the report found earlier in this article — has been engaging education leaders from across K-12 and higher education environments over the last two years exploring a lot of the same challenges with literacy that the task force will dive into over the next two months. One of the group’s “communities of practice,” called the NC Early Learning & Literacy Impact Coalition, included five university-based educator preparation programs and delved specifically into how to prepare teachers to be effective in teaching reading.

The group came up with two overarching recommendations: to ensure teacher candidates are deeply knowledgeable on a publication titled “The Science of Early Learning,” and to better align preparation with pre-service expectations. For a comprehensive look at how this group suggests those two things be done, go here.

Lee said other states have seen improvement in reading scores through a variety of strategies related to pre-service and in-service teacher training. Florida, for example, created a separate reading endorsement that schools of education were required to integrate into their elementary programs. For in-service teachers, the state requires teachers to acquire 40 hours of professional development related to literacy every five years. Those teachers with reading endorsements, Lee said, have been shown to lead to higher reading proficiency in the students they teach. Mississippi, on the other hand, focused its efforts on literacy coaches for elementary teachers in low-performing schools.

“So increasing teacher knowledge, changing teacher practice, coaches that support that, and then ultimately… increases in student achievement,” Lee said.

Highly-qualified individuals need to be selected to teach the preparation courses, lead professional development, and, in some cases, coach teachers on literacy instruction. “You can have all the policies you want but it all comes down to the implementation,” she said.

The task force is part of the State Board’s nine-part Guiding Collaborative Framework, which aims to redefine and re-create literacy instruction across the education system. The plan covers preparation, curriculum materials, beginning teacher support, ongoing training and coaching for high-needs schools, funding flexibility, summer reading camp improvement, and high-quality preschool with smooth transitions to kindergarten.

The task force will be divided into four subcommittees focused on professional learning, summer reading camp improvement, instructional resources, and pre-service preparation and licensure. The group will meet again next on January 23.