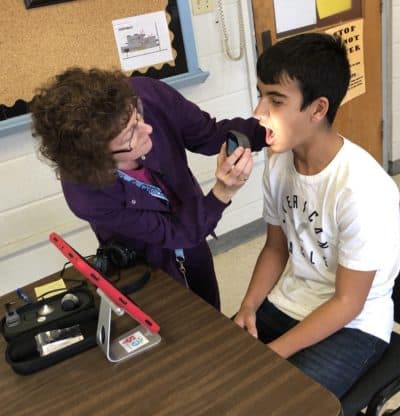

It’s the middle of the school day, and Jon has an ear ache that’s making it difficult for him to focus in class. He goes to the school nurse’s office, where an initial assessment is made. The nurse decides to set up a telemedicine appointment.

Within an hour, he’s sitting in front of an iPad with the nurse by his side while a medical provider on the screen makes an assessment. After diagnosing an ear infection, the provider sends an antibiotic prescription to Jon’s pharmacy.

Jon returns to the classroom, and his parents are notified about the diagnosis and prescription. His primary care provider is also notified. After work, Jon’s parents pick up the prescription. Jon is back in school the next day and already feels better after two doses of the antibiotic.

Without the telemedicine appointment, Jon’s parents may have had to leave work and take him to an urgent care center or his primary care provider — if they’re able to get an appointment. If it’s a reoccurring condition, Jon will miss even more classroom time. And if Jon’s family doesn’t have access to consistent medical care, an untreated chronic illness could increase absenteeism and negatively impact his academic performance.

This is just one example of the impact of telemedicine in schools. And in Duplin County Schools, appointments like this one happen all the time thanks to a partnership with a nearby university.

Duplin County, North Carolina

- Population: 58,741

- Race/ethnicity: 51% white, 25% Black, 23% Hispanic/Latino

- Poverty rate: 20.4%

- People without health insurance, under 65: 20.7%

- High school graduate or higher: 74.2%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts

The history

The East Carolina University (ECU) Brody School of Medicine and Duplin County — a rural county that sits just over an hour southwest of Greenville — have had a decades-long relationship. Dr. Doyle “Skip” Cummings, a professor and the director of research in ECU’s Department of Family Medicine, said the school’s mission is to improve the health status of the people of eastern North Carolina. That explains why 25 years ago the school partnered with the county to start a community health improvement process. Now, it explains why ECU partners with Duplin County Schools on a telemedicine initiative.

The American Academy of Family Physicians defines telemedicine as “the practice of medicine using technology to deliver care at a distance. A physician in one location uses a telecommunications infrastructure to deliver care to a patient at a distant site.”

“This particular project started off based on our concern for the health and well-being of children in Duplin County,” Cummings said. At the same time, a federal grant program provided funding to support telehealth in school-based intervention models. After connecting with the superintendent, principals, and school nurses, a telemedicine partnership between the university and Duplin County Schools was born.

The Healthier Lives at School and Beyond program, of which Cummings is the principal investigator, began at three schools — Warsaw Elementary, Wallace Elementary, and Beulaville Elementary. By its third year, the program had expanded to all 12 schools in the district. Here’s a look at the details, the impact, and the future of the program.

Healthier Lives at School and Beyond

- 2016-17 – Program set up

- 2017-18 – 88 completed visits (starting in January 2018)

- 2018-19 – 320 completed visits

- 2019-20 – 685 completed visits

The details

Three key components

Healthier Lives at School and Beyond offers three main components via telemedicine:

- Nutrition education counseling (weight management, healthy eating, diabetes, high blood pressure, etc.)

- Behavioral therapy (ADHD, depression, anxiety, trauma, conflict resolution, etc.)

- Acute minor medical care (sore throat, rashes, flu symptoms, ear ache, etc.)

ECU providers offer both the nutrition education counseling and behavioral therapy to students and staff in the district. Staff and faculty can self-report a need. For students, a nurse, social worker, guidance counselor, teacher, or other faculty will make the referral.

That referral comes to ECU, which collects pertinent information on the patient and obtains parental consent — both written and verbal — before scheduling the appointment. These appointments are often scheduled within a week or two.

All of these appointments take place during the school day, and parents are always invited to attend them alongside their child. Students go into a private room under the supervision of the nurse, social worker, or counselor and connect with the provider virtually. After the first appointment, the provider determines the frequency of follow-up appointments.

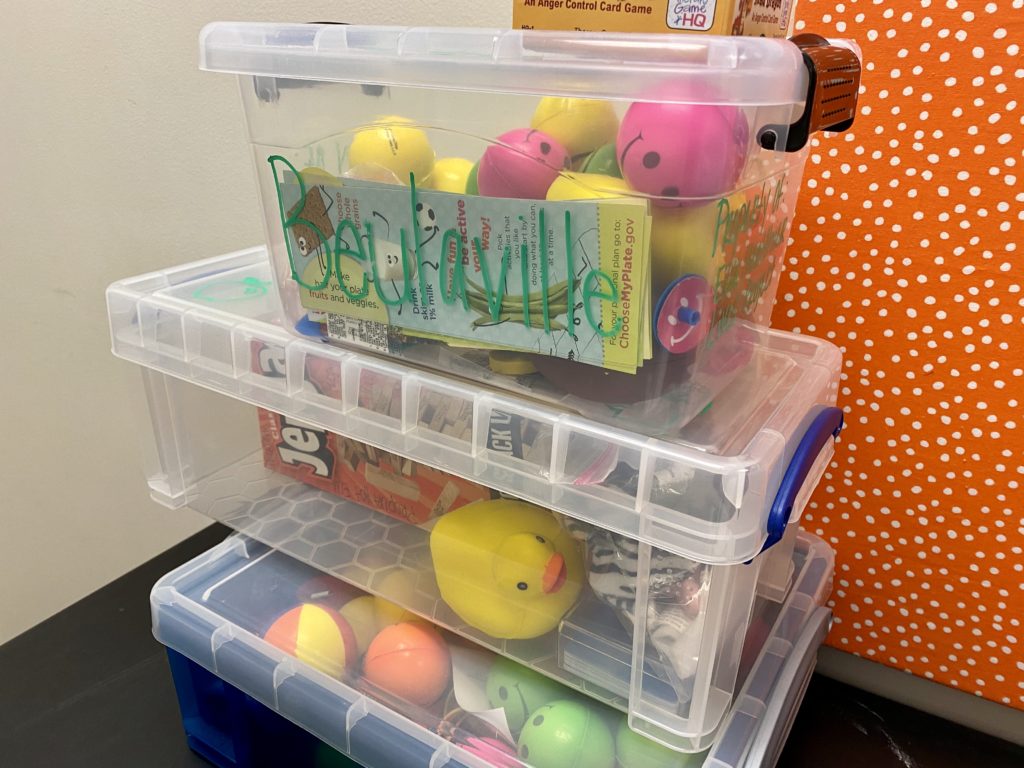

Cards sometimes used during behavorial therapy appointments. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

After their tele-appointment, students can select a small prize, just as they might at a physical doctor’s office. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

For acute minor medical care, the program partners with another organization, the Center for Rural Health Innovation, to provide services. While behavioral and nutrition services are free, acute care services are billed to the student’s insurance. That information is provided by the parents, along with their consent, before the student is able to access acute care.

If a student comes to the nurse’s office with an acute medical need, like a sore throat, the nurse performs an initial assessment. If a telemedicine appointment is necessary, the nurse will reach out to the Center. The appointment typically occurs within the next hour.

The student is seen alongside the nurse in their office, while the provider joins on an iPad or other screen. After making an assessment, if a prescription is needed, the provider can send it directly to the student’s pharmacy. If more care is needed, like a physical visit to a primary care doctor, efforts are made to ensure that happens.

“But in very many cases, an acute visit based on the nurse’s assessment happens right then. The situation is resolved and the child is able to go back to school, the parent is notified, and the physician is notified,” said Jill Jennings, a clinical nutrition specialist at ECU and program manager for Healthier Lives at School and Beyond.

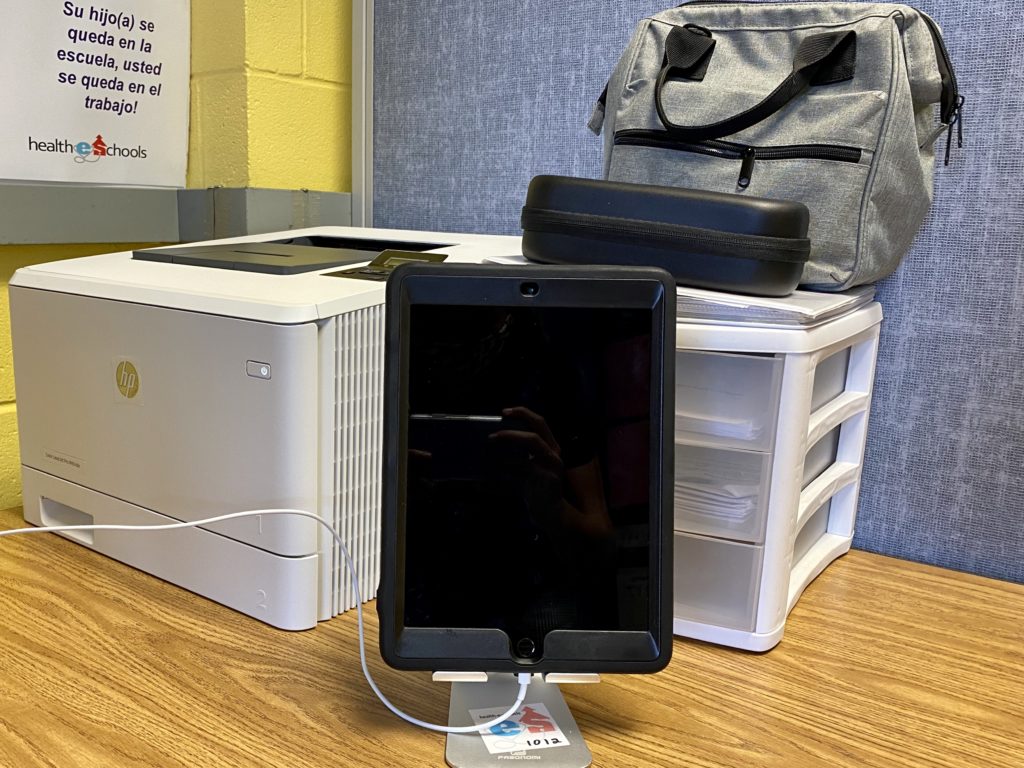

When the program began, the original participating schools received large telehealth equipment carts. But that equipment was cumbersome and complicated. Now, every school in the district has a portable telehealth unit that fits inside a lunchbox.

The hand-held equipment in the right-hand photo below, which fits inside the lunchbox, allows nurses to quickly provide all the information the provider needs to make a diagnosis. Using a video-enabled device that streams back to the provider, they can look into an ear, take a student’s temperature, and more.

Students at Beulaville Elementary connect with providers for acute telemedicine appointments using this iPad. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

This device allows nurses to conduct exams during acute care telemedicine appointments by using an otoscope, stethoscope, and a non-contact forehead thermometer and digital camera. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

Pivoting amid the pandemic

The program relies on students being in school buildings, so it has faced a few bumps in the road. Two major events prevented the program from reaching students: Hurricane Florence in 2018, which led to the closure of Duplin County Schools for more than a month, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

After closing for in-person instruction in March, the district reopened under plan C, or fully remote, in August. It then switched to plan B, a hybrid model, in late September. So the program decided to take on a new approach.

“Particularly with the schools starting out all virtual for the first five weeks, we were concerned, as a project, [about] how we were going to be able to connect to students,” said Cummings. “And so we came up with literally a crazy idea.”

They called the transportation department at ECU and asked if they could provide a Wi-Fi enabled bus that could be retrofitted into a mobile medical van.

The department said yes. They took rows of seats out of a large bus that ECU athletes normally ride in and outfitted it with tables and partitions to create two medical exam rooms. And, the department provided a driver who gives up an entire day every week to drive the bus to Duplin County alongside ECU providers.

This fall, the bus has focused on providing physicals. North Carolina requires that every kindergartner receive a health assessment in order to remain in school. Students that move to North Carolina from out-of-state also have to complete a physical to stay enrolled.

This year, the deadline for these exams was extended to the end of October due to COVID-19. But the local health departments and physicians who normally conduct them are focused on combatting the COVID-19 pandemic.

So the ECU team planned visits to every elementary school in the district. School nurses schedule all of the students who need a physical exam, and ECU pediatricians conduct them on the bus. They also bring along translators when needed.

The pediatricians fill out paperwork, identify students who haven’t had immunizations, and write referrals for students who have nutrition and behavioral health needs. After the visit, every student gets a book, a healthy snack, and a sticker.

Dr. Kristina Simeonsson, the primary ECU pediatrician on the bus visits, said she was on board with the idea as soon as the opportunity arose to serve students in a different way. Beyond conducting the physicals, Simeonsson said the trips are a chance for students and families to see the Healthier Lives at School and Beyond program in action. Students meet providers who they might eventually connect with via telehealth and learn more about all the services the program offers.

“They’ll come off the bus and then they’ll meet with a nutritionist or talk to people about the program, and they’re all in,” she said.

The success of the bus initiative is a product of a team effort. Jennings credits the school nurses for making it all happen.

“It requires a tremendous amount of organization and willingness to participate in an entire day. And we arrive, and they’ve got all the paperwork lined up and ready to go. They know exactly who’s coming in at what time,” said Jennings. “And each child that receives their physical … is a child that gets to stay in school.”

Beulaville Elementary in Duplin County was one of three schools included in the first year of the Healthier Lives at School and Beyond program. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

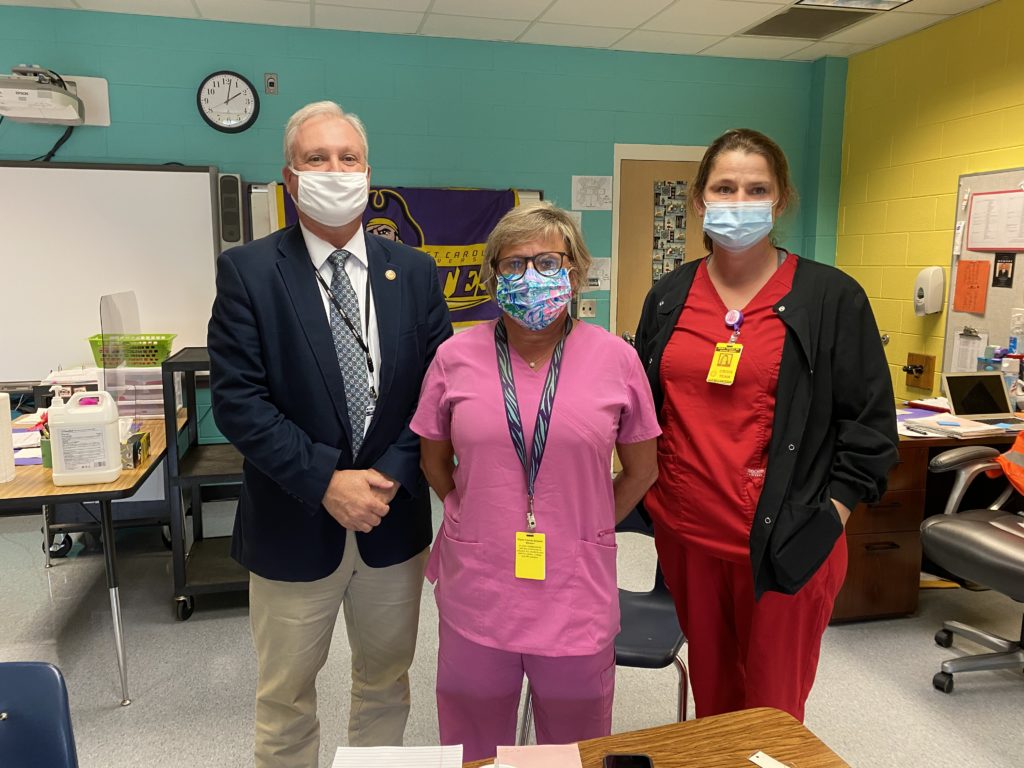

From left to right, Cary Powers, assistant superintendent in Duplin County Schools; Sue Ellen Cottle, lead nurse; and Marla Whaley, school nurse at Beulaville Elementary. Analisa Sorrells/EducationNC

The impact

Before the program began, Sue Ellen Cottle, lead nurse for Duplin County Schools, said it was difficult for students to get doctors’ appointments, even for simple things like ear infections. They might miss two days of school just waiting to get one. Now, they can often see a provider within an hour, and their parents don’t have to leave work. Assuming they aren’t infectious, students can more quickly return to the classroom, thus reducing absenteeism.

“Keeping the child actually in the classroom … where they can continue to get their education and their social development with other kids is indeed very valuable,” Cummings said.

The same goes for staff, who can now book telemedicine appointments during their planning periods, reducing the number of sick days they have to take and limiting the number of substitute teachers the district has to hire. Cummings said roughly 40% of the program’s acute medical visits are for teachers and staff.

The program also provides much-needed access to behavioral and nutritional services that are hard to come by in Duplin County. As of 2017, there was less than one (0.3) psychologist or psychiatrist per 10,000 people in Duplin County. Cottle said families usually have to drive more than an hour to Jacksonville, Wilmington, or elsewhere for that care. Now, students can easily connect with therapists and nutritionists on a weekly basis.

Every school in Duplin County has a dedicated school nurse. For comparison, 58% of school nurses in North Carolina split their time between two or more schools.

Marla Whaley, school nurse at Beulaville Elementary, said that the behavioral health visits have been especially crucial for her students. After the appointment, the providers reach out to the students’ teachers to offer techniques and modifications that might help the student in the classroom. They also connect students to outside resources to ensure they receive all of the support they need.

She recalled a particular student who was experiencing low self-esteem due to her weight. After working with a nutritionist via telemedicine on both healthy eating and exercise, Whaley said she flourished.

“Her self-esteem grew, she joined our Girls on the Run, she changed some of her eating habits,” Whaley said. “She did lose weight and became a little bit more outgoing through that process.”

Both Jennings and Cottle emphasized that the services provided through the program are not meant to replace the care of a primary care provider. Rather, they serve as a bridge between the two.

“It truly has been a community effort … of the kids feeling comfortable, the parents feeling comfortable taking advantage of these services, because there certainly is a need,” said Cary Powers, an assistant superintendent in Duplin County Schools. “We hope this partnership continues for a long time.”

Lessons learned

Reflecting on the program, Cummings and Jennings said:

- Functional equipment matters. After switching from complex technology carts to hand-held technology, appointments were easier and smoother to conduct.

- Boots on the ground are critical. Having school nurses, counselors, social workers, and a logistics coordinator in Duplin County ensures the success of the program, even though the medical services are provided virtually.

- Build continuous feedback loops. ECU has altered various aspects of the program based on direct feedback from school nurses.

- Think long-term. Even if immediate changes aren’t seen, behavioral and nutritional services are “planting the seeds” for better decision-making down the road that supports students’ overall health.

The future

Healthier Lives at School and Beyond was originally funded by a $1.2 million grant through the federal Health Resources and Services Administration. Now, the majority of the program’s funding comes from the Anonymous Trust.

Jennings said the model that worked before COVID-19 is not the same model that works now. Their funding relationship with the Anonymous Trust has allowed them the flexibility to rethink their approach and explore new avenues of supporting students in Duplin County.

They are also thinking about how to make the initiative self-sustainable. Cummings said that billing insurance is challenging since parents are not always readily available during the school day and because services like behavioral health and nutrition counseling are not always covered. Eventually, he hopes to make an economic case for state funding of the program. Cummings says the services save the state money by keeping kids in school and keeping teachers and faculty at work.

Early next year, the project plans to expand to nearby Jones County Public Schools. And when asked to dream big, Cummings said he hopes to see the model expanded across all of the rural, underserved communities in eastern North Carolina.