Disclaimer: This student paper was prepared in 2020 in partial completion of the requirements for Public Policy 804, a course in the Masters of Public Policy Program at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. The research, analysis, and policy alternatives contained in this paper are the work of the student team that authored the document, and do not represent the official or unofficial views of the Sanford School of Public Policy or of Duke University. Without the specific permission of its authors, this paper may not be used or cited for any purpose other than to inform the client organization about the subject matter.

Executive summary

This report provides a landscape analysis of the ways in which schools across North Carolina deliver health services. We identify five categories of health service delivery: school nurses, school health centers, telehealth, university partnerships, and miscellaneous programs. The report also features exemplary programs or “bright spots” in the state that other school districts, individual schools, or organizations could adopt. The bright spots include:

- A mental health university partnership involving Appalachian State University, Ashe County Schools, and RTI International;

- A school health center at Apple Valley Middle School in Hendersonville;

- The Center for Rural Health Innovation, a rural school health center operator that uses telehealth;

- Motivating Adolescents with Technology to CHOOSE Health™ (MATCH Wellness), a nutritional health program; and

- The Emerald School of Excellence, a recovery high school in Charlotte.

These programs are notable for their relative affordability, accessibility, quality, and/or replicability.

Why deliver health services through schools

Healthy students are crucial to the success of public education. When students are absent from school due to illness, they miss essential learning and may fall behind their peers. An early demonstration of this connection between student health and school attendance took place in 1902 when New York City hired a nurse to work in schools in an effort to improve student attendance. One year after implementing the pilot program, student absenteeism due to illness decreased by 99%.1 Throughout the 20th century, researchers continued to expand their understanding of the connections between student health and educational outcomes. Education and public health officials now accept this connection as common knowledge.2

As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted, social determinants of health play a critical role in long term health outcomes and life expectancy.3 According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Community Preventive Services Task Force:

Children from low-income and racial or ethnic minority populations in the U.S. are less likely to have a conventional source of medical care and more likely to develop chronic health problems than are more-affluent and non-Hispanic white children. They are more often chronically stressed, tired, and hungry, and more likely to have impaired vision and hearing—obstacles to lifetime educational achievement and predictors of adult morbidity and premature mortality.4

Thus, provision of health services through schools is one significant way to increase access to medical care, especially for historically underserved communities.

Landscape analysis

We have identified five broad categories of health service delivery in schools: school nurses, school health centers, telehealth, university partnerships, and miscellaneous programs. Overlap exists among these categories, with some programs blending elements of more than one category.

School nurses

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 mandates that Local Education Agencies (LEAs) provide a school nurse when a child has a health condition representing a barrier to their learning.5 During the 2015–2016 school year, North Carolina had 1,318 school nurses serving 2,313 schools. School nurse programs may be operated by LEAs, local departments of health, or other health-related agencies.6

School nurses serve as the first line of defense when a child needs medical attention during the school day. They are often the only licensed health care provider in a school and administer care during emergency health situations. School nurses work with families and school staff to create an individual care management plan for students with chronic health needs.7 School nurses are also responsible for maintaining the public health of schools. They often conduct health screenings (e.g., vision and hearing) and administer immunizations to prevent communicable diseases. Though nurses can administer prescription medications, they cannot write prescriptions. They instead help connect students with external care and specialists as needed.8

The State Board of Education recommends a ratio of one nurse per 750 students. However, only 46 of 115 LEAs met this recommendation in the 2015–2016 school year. The annual statewide cost of meeting this recommendation would be $45 million.9 The National Association of School Nurses recommends one nurse per school. Adhering to this recommendation would cost the state $79 million annually.10

As a result of the school nurse shortage, 58% of the school nurses in North Carolina split their time between two or more schools.11 School staff often take on the role of basic medical providers when school nurses are unavailable. These employees perform an estimated 60% of all medical care in schools (e.g., supplying an ice pack or bandage to an injury).12

School health centers

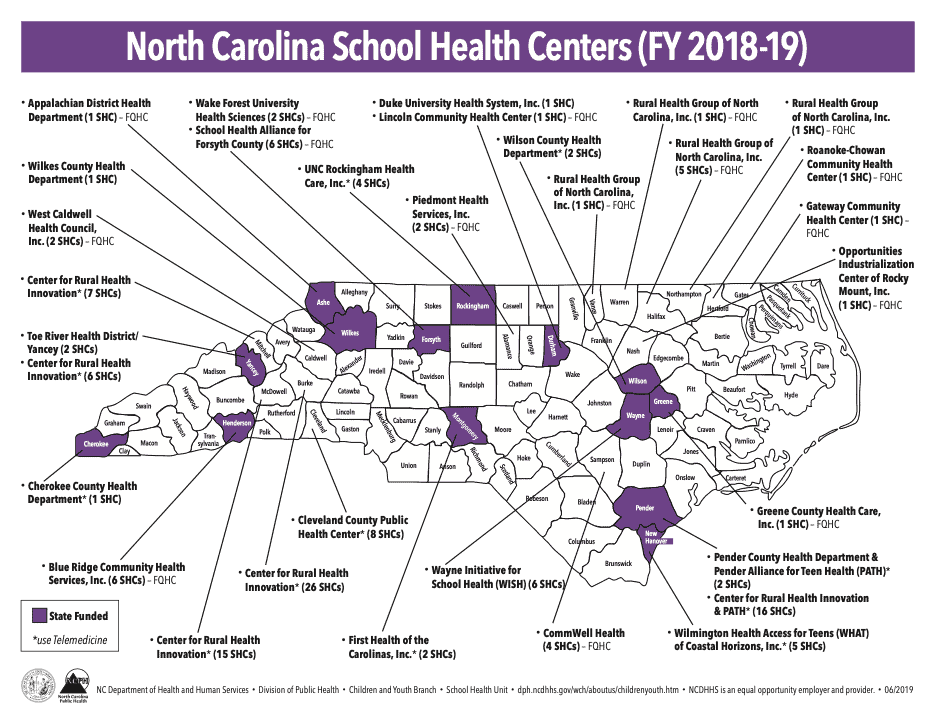

School health centers (SHCs) have emerged across North Carolina in the last 30 years to fill the health care gaps that school nurses cannot fill alone. At least 140 SHCs across 28 counties now serve more than 130,000 children.

Though exact services vary by school, SHCs share some common defining features. SHCs are usually located in a repurposed classroom space or a standalone structure on the school property. SHCs employ at least one advanced practitioner—a physician, physician assistant and/or nurse practitioner—to see students throughout the school day. Unlike school nurses, the advanced practitioner is qualified to prescribe medications to students and families. NCDHHS divides the most common SHC services into the following four categories:

- Medical services—chronic disease and routine primary care,

- Preventive services—well-child check-ups and immunizations,

- Nutrition services—eating disorders, health education, and sport physicals,

- Behavioral health—mental health screenings, therapy, and referral.13

During the 2018–2019 school year, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) distributed grants to 31 of the 140 SHCs across North Carolina.14 NCDHHS has designed a competitive grant proposal process for distributing its $1.4 million SHC budget to health-related nonprofits or other agencies. Each recipient receives a $44,400 grant for one academic year.15 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)—community-based clinics that receive federal funds to provide primary health care in underserved areas—sponsor an additional 36 SHCs in North Carolina.16 The remaining SHCs receive funding from federal or state grants, county health departments, nonprofit organizations, charitable foundations, or health insurance companies.17

Telehealth

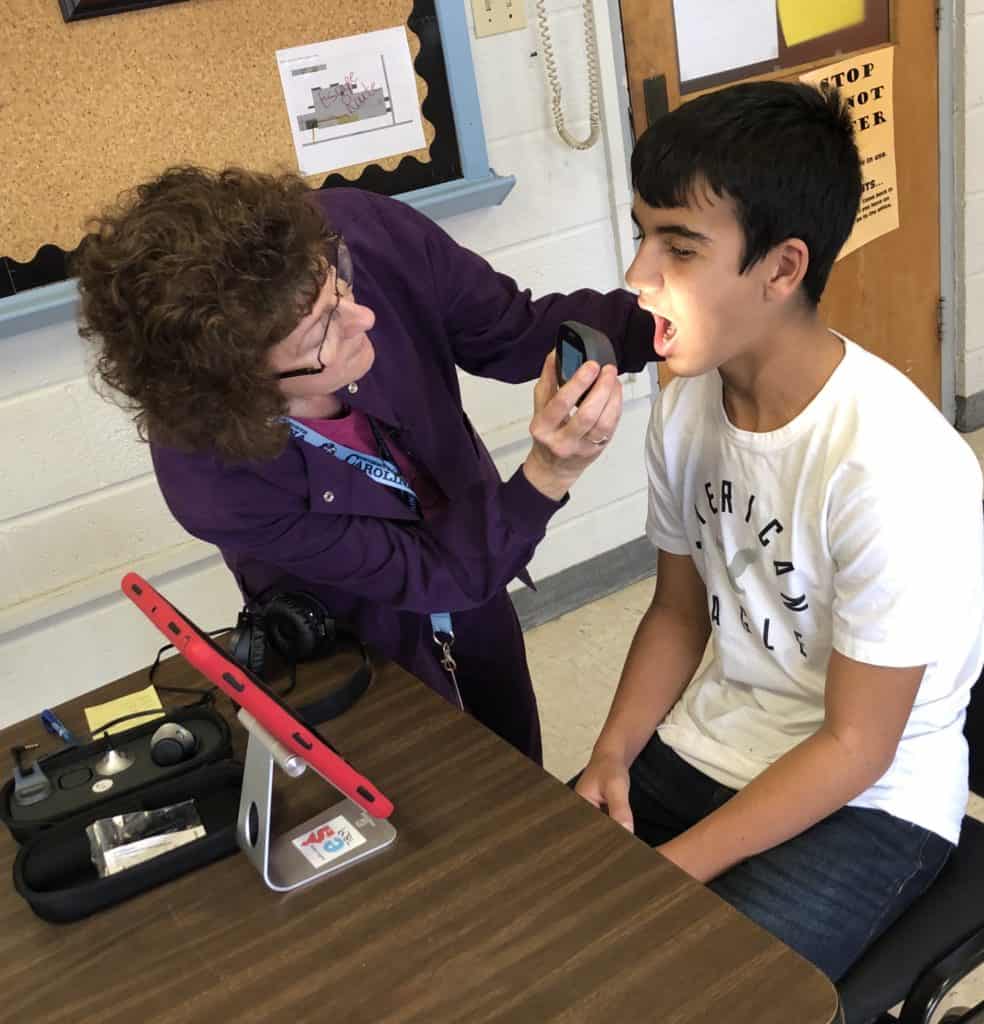

Telehealth is a fast-emerging model with great potential for North Carolina schools, particularly those located in rural areas. More than one hundred SHCs across the state incorporate telehealth in some capacity.18 Unlike traditional SHCs, which require a dedicated physical space, telehealth enables advanced practitioners to operate remotely. Telehealth units avoid the costs associated with maintaining a large physical space because they fit within preexisting facilities dedicated to student health inside the school. Telehealth also bridges the health service delivery gap between rural and urban communities.

Telehealth program expansion is likely to continue as the technology develops, further lowering overhead costs associated with installing telehealth infrastructure in schools. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic may accelerate the development of telehealth technology and implementation to accommodate for future social distancing measures.19

Telehealth functions through a “hub-and-spoke” model that can complement other forms of school health delivery.20 An advanced practitioner serves as the hub, diagnosing hundreds of students across several schools from another location—for example, a medical office or a health center at another school. School-based staff are the spokes operating the telehealth equipment and connecting the patient to the practitioner. Though school nurses often fill this role, no medical license is required to operate telehealth equipment; any school staff member can be trained to function in this role.21

Funding streams are available for telehealth through NCDHHS and county health department grants, nonprofits, and private donors. The Duke Endowment previously invested in school telehealth in western North Carolina due to its innovative nature.22 Atrium Health also launched its own school-based telehealth program in 2017. A $750,000 grant from BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina in 2019 expanded this work across Cleveland County. Click here for more about BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina’s grantmaking.23

University partnerships

North Carolina boasts a number of research universities. These include two of the country’s top 50 NIH-funded institutions: the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Duke University.24 Any university can partner with entities in their communities, such as school districts and nonprofits, to provide student health services. These services may include physical health, behavioral health, nutrition, child welfare, and mobile crisis response, among others.25

Studies show that university partnerships are an effective method for improving educational outcomes. For example, Milwaukie High School (MHS) in Milwaukie, Oregon, maintains several community partnerships, including two with universities. One partnership is with the University of Oregon Health Sciences centered on social work. Another is with Oregon State University and focuses on nutrition services. Since implementing these partnerships, MHS has seen a 7% increase in daily attendance as well as significant improvements in reading, math, and writing proficiency.26

Funding streams for university partnerships generally come from government grants or community donations. One such partnership, North Carolina Integrated Care for Kids (InCK), received a multi-million-dollar grant in January 2020 from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). InCK is a partnership among Duke University, UNC, and NCDHHS.27 One of eight CMS grants awarded to develop integrated local care delivery models for children, InCK aims to integrate school and medical records for children who are insured through Medicaid CHIP within the same database. Through InCK, a doctor can see school data previously protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), such as if a student received mental health care from a school counselor. InCK seeks to link school and Medicaid data to develop single plans of care for each student. The partnership will implement InCK as a pilot program in Alamance, Orange, Durham, Granville, and Vance Counties over the next seven years.28

Miscellaneous programs

A variety of other school health services are available across the state and may be viable options for replication. These programs tend to target more specific aspects of student health — nutrition, oral health, mental health, addiction recovery — and thus do not fit neatly into one of the larger established categories. They typically receive funding from private donors, nonprofits, insurers, charitable foundations, and/or government grants. Several examples are highlighted in the following section.

Bright spots

Many programs deliver health services in schools across North Carolina. Our report is not a comprehensive accounting or assessment of those programs. Rather, this section features five “bright spots” — successful models of school health service delivery worth replicating at other locations throughout the state. We evaluated these bright spots using four criteria: cost of implementation, accessibility to students, quality of care provided, and ease of replicability.

Methodology

To help identify bright spots, we developed a 15-question survey on school health service delivery to public school teachers across North Carolina. We disseminated the survey using EducationNC’s Reach Toolkit in February 2020. Click here for a link to the results. The survey gathered information from educators on the ground about the state of health service delivery in North Carolina’s public schools.

The survey received 456 respondents. However, only 42 left enough contact information for us to follow up with them about their responses. About 45% of respondents said that their schools did not provide either adequate health services or any services at all. In reference to the intermittent availability of school nurses, one respondent quipped, “Kids don’t only conveniently get sick on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and select Fridays.” Over half of respondents said that their schools provided behavioral health services. Majorities also said that their schools did not provide either medical or nutrition services. Only 33% of respondents said that their schools provided preventive health services.

We also conducted a series of 15 interviews between February and April 2020. We identified most interview participants through our own independent research. Interviewees included school health experts, nonprofit leaders, researchers, government agencies, and educators.

We selected one teacher to participate in an interview due to her robust responses to the Reach Toolkit survey. Our interviews filled knowledge gaps that we could not address through research and survey data alone. Interviewees provided the narrative of how and why programs began, discussed how the programs are administered, and explained funding streams in greater detail. The interviews were semi-structured and included a series of baseline questions.

Appalachian State University ASC Centers

In December 2019, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) awarded a $2.5 million grant to a partnership involving Appalachian State University (ASU), Ashe County Schools, and RTI International. The partnership supports the development of Assessment, Support, and Counseling (ASC) Centers in rural North Carolina.29 It relies on a “medical center model” that allows trainees in clinical psychology at ASU to provide pro bono care to students currently on waitlists under the supervision of experienced practitioners.30

| Cost | The five-year, $2.5 million ED grant comes at no cost to the schools. Over the course of the grant, ASU expects to receive over $800,000. The grant scales up the existing partnership between ASU and rural schools.31 |

| Access | A large number of students have received referrals for behavioral health services but face long waitlists or logistical/economic challenges. This partnership affords those students immediate access to care at ASC Centers at no cost to patients or their families.32 |

| Quality | A 2013 ASU study in one western North Carolina school found that students who referred to ASC Centers improved or recovered from “clinically significant” symptoms 63% of the time. 33 In addition, a 2020 issue brief on youth mental health in the North Carolina Medical Journal illustrates how ASC Centers implement “effective and sustainable practices” to treat those who exhibit suicidal characteristics.34 |

| Replicability | This specific grant supports operations in Alleghany, Ashe, and Watauga Counties. Other counties across the state are working to create their own initiatives based on the ASC Center model. East Carolina University is working to scale up a similar partnership. Other states, including Florida, Montana, and Utah, have also begun implementing their own partnerships.35 |

Apple Valley Middle School

Apple Valley Middle School renovated a classroom in 1996 to serve as a school health center (SHC). The center now houses a full-time physician assistant, nurse, and two social workers. A dietician also visits the center several times a month to teach nutrition lessons in classrooms, conduct body mass index (BMI) screenings, lead nutrition and eating disorder counseling sessions, and meet with sports teams.

| Cost | According to Tammy Greenwell, the chief operations officer (COO) of Blue Ridge Health, it typically costs $30,000 to renovate a classroom space for its SHCs. Greenwell encourages schools to fundraise or find grants to cover this cost before Blue Ridge rolls out a new SHC.36 Blue Ridge Health, the sponsoring FQHC, pays the salaries of medical staff along with any additional expenses. Roughly 70% of Blue Ridge Health’s operating budget comes from health insurance reimbursements. The rest of its budget comes from grants and private donors.37 |

| Access | Students who attend Apple Valley Middle or the neighboring high school can visit the SHC for medical or mental health needs during regular school hours with parent permission. About 95% of students are enrolled in Apple Valley’s SHC, and about 700 (out of 855 students) use it at least once per year. Apple Valley’s SHC enrollment numbers increased significantly once it integrated parent permission forms into school registration packets.38 |

| Quality | SHCs can improve access to medical care in health deserts like rural North Carolina.39 Capturing outcome data is challenging due to regulations under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and FERPA. However, Blue Ridge Health has established a confidential data sharing agreement with the school district to collect attendance data. According to Greenwell, Apple Valley students who frequent the SHC have improved attendance records.40 |

| Replicability | SHCs can operate in both rural and urban school environments. To be replicable, a community needs a sponsor (e.g., an FQHC, nonprofit, private foundation). The sponsor can then apply for state or federal grant funds to cover the cost of building renovations and medical staff. Additional financial support from foundations, local nonprofits, and private donors is necessary to cover the ongoing operating costs. |

Center for Rural Health Innovation

The Center for Rural Health Innovation (CRHI) operates SHCs from its headquarters in the western part of the state. CRHI relies on thirteen dedicated staff members, as well as school nurses and telehealth, to deliver health services via its Health-e-Schools program at 107 locations in schools across North Carolina.

| Cost | CRHI operated on a $570,000 budget for fiscal year 2020 but at no cost to schools. Funding for that year came primarily through charitable grants from sources such as the Duke Endowment and the Children’s Health Fund. Schools contribute space and personnel for operating the Health-e-Schools telehealth equipment, typically a school nurse and the school nursing office. |

| Access | CRHI’s policy is to see every patient regardless of insurance or ability to pay. Every student and staff member at schools with Health-e-Schools equipment (purchased by CRHI from TytoCare, a telehealth equipment company) is eligible to receive care. Parents/guardians must grant permission for their children to participate. The focus of the program is “equity and equitable access.”41 |

| Quality | As noted elsewhere in this report, abundant evidence demonstrates that SHCs improve student health outcomes.42 CRHI incorporates telehealth to expand access to students who otherwise would not be able to utilize SHCs. CRHI has not had the financial means to pay a researcher to evaluate its program outcomes. The fact that Health-e-Schools has been in operation since 2009 and continues to expand, even consulting on how to implement similar models in other states, is the best available evidence of its success. |

| Replicability | Health-e-Schools can operate in any school or district. CRHI’s hub-and-spoke model is particularly well suited for students in rural areas who may not have easy access to health services. Providers based in one part of North Carolina can easily advise school staff via telehealth on how to provide appropriate care and support for students anywhere else in the state. |

Emerald School of Excellence

Emerald School of Excellence is North Carolina’s first recovery high school (RHS). It is a private school which opened for enrollment in Charlotte in the 2019–2020 academic year. RHSs provide accredited education and substance abuse treatment in tandem. They offer students a smoother transition back to an educational setting after completing an in-patient treatment program.43

| Cost | Tuition costs $1,000 per month, with partial and full scholarships available from private donations. The school’s goal is never to turn anyone away based on inability to pay.44 |

| Access | Although located in Charlotte, the school’s Executive Director emphasized, “Just know that we’re an option for anyone that’s able to get to us. There are families looking at us from all parts of North Carolina. If they’re willing to drive to and from or have friends and family locally where the student can stay, we could be an option.”45 |

| Quality | RHSs have been around since the 1970s and have expanded to more than 40 campuses nationally. The opioid crisis has spurred new interest in this model.46 One study found that students who attended an RHS after treatment were significantly less likely to return to substance abuse or be absent from school after six months.47 |

| Replicability | RHSs are best suited for urban settings due to student density. But they can also serve students from surrounding areas who have access to transportation. North Carolina’s second RHS—Wake Monarch Academy—is already in development in Wake County, with an expected opening in 2021.48 |

MATCH Wellness

The MATCH (Motivating Adolescents with Technology to CHOOSE Health™) program was established in 2006 by Tim Hardison, who was a science teacher at Williamston Middle School at the time. Hardison created a curriculum for teaching students to make healthy nutrition and fitness choices after learning Martin County residents had the shortest life expectancy in the state due to high rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.49 Hardison has designed the curriculum for incorporation across all seventh grade courses and in alignment with the N.C. Standard Course of Study.

| Cost | The cost of implementing the MATCH Wellness program is about $100 per seventh grader annually. This price includes student workbooks, access to online materials, training for participating teachers, and stipends for school and district liaisons to manage implementation. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed)—a federal program designed to support the health and wellness of people who are eligible for SNAP benefits—is its primary source of funding.50 It pays MATCH Wellness directly on behalf of participating school districts. |

| Access | Every seventh grader enrolled in a district with MATCH is automatically a participant in this program. MATCH currently has 11,000 students enrolled.51 |

| Quality | Early in its development, MATCH partnered with researchers at East Carolina University, who helped manage the program and studied its results. These researchers consistently found statistically significant reductions in the BMI scores of two-thirds of students.52 One East Carolina study found lower rates of obesity among participants four years later, when compared to a control group.53 |

| Replicability | Hardison designed MATCH Wellness with replication in mind. It can be implemented in any North Carolina school district as long as funding is available. Hardison suspects an increase in demand would lead to a corresponding increase in funding availability through government programs such as SNAP-Ed.54 |

Conclusion

Many schools across North Carolina connect students to health services via school nurses, school health centers, telehealth, university partnerships, and other miscellaneous programs. The examples highlighted in this report can serve as models worth replicating throughout the state. Providing health services through schools in any significant capacity can improve student health and educational outcomes, especially in terms of attendance. When students can receive medical support through schools, they miss less class time and have fewer absences. As teachers across the state commonly say about their students, “You can’t teach them if you can’t reach them.”

Recommended reading