Share this story

- Whether you’re a N.C. policymaker, education advocate, or resident wanting to learn more about North Carolina’s 58 community colleges, this guide is for you.

- The NCCCS serves hundreds of thousands of students across the state each year. This year, the system is asking lawmakers for a $232 million increase in state funding over the next two years to expand its impact.

|

|

Community college changed Paralee Cox’s life.

Cox graduated from Blue Ridge Community College last May with a credential in surgical technology. Before graduating, Cox was hired by Pardee UNC Health Care as a surgical technician and won the N.C. Community College System’s (NCCCS) Dallas Herring Achievement Award out of 58 nominees across the state.

Only eight years before, Cox received a 60-month federal prison sentence for drug-related charges. After her release, community college helped Cox dream about her future – not letting her struggles or prison sentence define her.

“My thing would be just to show others that it’s possible to get help and it’s possible to overcome your battles, no matter what your background may look like,” Cox told EdNC last May. “…There are people here who can help you. You just have to continue to knock on the doors and eventually one will open.”

Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

The NCCCS serves hundreds of thousands of students each year – meeting the needs of students from all different backgrounds through its 58 unique institutions across North Carolina.

Despite such student impact, the system has seen years of enrollment declines, accentuated by the pandemic. This year, the system is asking lawmakers for a $232 million increase in state funding over the next two years. NCCCS leaders say that funding will help community colleges expand their impact for students and help meet workforce demands.

Last month, the joint education appropriations committee of the N.C. General Assembly heard an overview of the community college system in preparation for this year’s state budget creation process. The meeting included discussing the structure, enrollment, and funding model for the system, along with a budget preview. You can view the Feb. 16 presentation here, along with a list of each college’s full-time equivalent (FTE) budget appropriation.

In the subheadings below, we explain each topic using the Feb. 16 presentation and EdNC’s previous reporting. Whether you’re a policymaker, education advocate, or resident wanting to learn more about North Carolina’s 58 community colleges, this guide is for you.

What is the NCCCS?

The N.C. Community College System enrolls about 575,000 students in one or more courses throughout the year. It consists of 58 colleges, making it second only to California in its number of colleges. Several N.C. community colleges also have multi-campus centers, or more than one campus students can attend.

The state’s community colleges contribute about $19.3 billion to the state’s economy each year, according to a 2022 economic impact study partially funded by the N.C. legislature. The study found that the system supports 319,763 jobs and employs 36,422 people.

The NCCCS was founded in the early 1960s to provide accessible postsecondary education to any student regardless of prior educational experience. The late W. Dallas Herring, the “father” of the NCCCS, viewed education – and community colleges – as “opportunity for all the people.” Today, community colleges, in North Carolina and beyond, enroll some of the most diverse student populations.

The mission of the system is “to open the door to high-quality, accessible educational opportunities that minimize barriers to post-secondary education, maximize student success, develop a globally and multi-culturally competent workforce, and improve the lives and well-being of individuals.”

For some students, those open doors look like a high school diploma. For others, an open door is a short-term workforce credential or university transfer degree. NCCCS students consistently account for the majority of transfer students into the UNC System, Stephen Bailey, a staffer of the legislature’s Fiscal Research Division, told lawmakers at the Feb. 16 meeting.

Other “open doors” include certificates, apprenticeships, technical degrees, and more.

As a state, we expect a lot of our community colleges, especially our small, rural colleges, EdNC’s CEO Mebane Rash wrote last week.

In addition to their core functions, community colleges play a critical role in child care – both training the early child care workforce and in some cases providing on-site child care themselves – provide mental health resources for their communities, train local law enforcement and health care workers, teach English language learners, and much, much more.

“It’s called a community college for a reason, because it’s in your community,” Sen. Bobby Hanig, R-Bertie, said at the meeting. “If we start taking away community colleges, we are shooting ourselves in the foot. These folks provide an unimaginable resource for especially rural areas that don’t have the opportunity to be 10 minutes from the university.”

Governance and structure

The same section of the state constitution that instructs the General Assembly to establish the UNC System allows lawmakers to establish other institutions of higher education, such as the NCCCS.

“And so the General Assembly did deem it wise to create the community college system,” Bailey told lawmakers.

The state’s general statutes outline the community college system and its laws in Chapter 115D:

The major purpose of each and every institution operating under the provisions of this Chapter shall be and shall continue to be the offering of vocational and technical education and training, and of basic, high school level, academic education needed in order to profit from vocational and technical education, for students who are high school graduates or who are beyond the compulsory age limit of the public school system and who have left the public schools, provided, juveniles of any age committed to the Division of Juvenile Justice of the Department of Public Safety by a court of competent jurisdiction may, if approved by the director of the youth development center to which they are assigned, take courses offered by institutions of the system if they are otherwise qualified for admission. The Community Colleges System Office is designated as the primary lead agency for delivering workforce development training, adult literacy training, and adult education programs in the State.

Statement of Purpose for community colleges in N.C. General Statutes, emphasis added by EdNC

The governance structure of the system involves two primary governing bodies. The State Board of Community Colleges serves as the governing authority for the system, setting system policies and regulations. That Board also elects the system president, who leads the community college system office. There are 21 members of the State Board – 18 appointed and three ex-officio.

Each of the 58 colleges also has a local board of trustees. These independent boards serve as the governing authority for each college. They can set independent policies if they wish to and elect their college’s president. Each local board must have a minimum of 13 members, of which 12 are appointed and one is ex-officio.

The State Board of Community Colleges is evenly split between registered Republicans and Democrats, according to data presented by Davidson College to the Governor’s Commission on Public Higher Education Governance earlier this month.

Almost 70% of Board members are male and around 70% are white, according to this same data. Among community college boards of trustees, 62% are male and 80% are white. Out of 790 total institutional trustee members, only 8 are Asian and 11 Hispanic.

Enrollment and tuition

Community colleges have three major instructional areas:

- Curriculum: Credit courses that lead to certificates, diplomas, or associate degrees. This includes arts and sciences programs and career and technical education, along with various special programs.

- Workforce continuing education: Non-credit courses that provide job training opportunities, spanning myriad programs. Some include aircraft systems, auto maintenance, business, health occupations, and more.

- Basic skills: Includes Adult Basic Education, GED, Adult High School, English as a Second Language (ESL), and Compensatory Education.

In 2021-22, 45% of community college students statewide enrolled in curriculum programs, 43% in workforce continuing education, 7% in basic skills, and 5% in multiple instructional programs, according to Fiscal Research Division.

More than half of the system’s students are 25 or older, according to 2021-22 headcount data. In recent years, the system has increased its efforts to serve adult learners, or students 25 and older.

Despite such efforts, the system’s enrollment is declining.

The NCCCS saw a 17% decrease in headcount from fall 2019 to fall 2020 — the first year of the pandemic. While headcount has increased since 2020, new data on fall 2022 headcount shows there are still 44,000 fewer students enrolled than before the pandemic, which represents a 10% decrease.

While the pandemic exacerbated enrollment declines, it did not create them. Enrollment has been trending down since it peaked during the Great Recession in 2010-11.

Generally, community colleges don’t deny admittance to any students who apply, unlike four-year universities. The Board code outlines minor exceptions.

“There really is a tremendous range in terms of the students’ academic competencies, education goals across the system,” Bailey told lawmakers.

In addition to their accessibility, community colleges are also generally more affordable than four-year colleges and universities. Tuition for full-time, in-state curriculum students is $2,432 per academic year, the cheapest among N.C.’s regional counterparts according to Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) data. That cost has risen about $800 since 2009-10.

In comparison, yearly tuition rates at UNC System institutions range from $3,400 to over $7,000. The NC Promise Tuition Plan allows resident undergraduate students at four select universities to pay an annual tuition of $1,000.

Many community college students don’t pay the full tuition, Bailey told lawmakers.

Some N.C. community colleges offer promise programs, which pay for some or all tuition and fees for eligible residents within their service areas. The Longleaf Commitment Grant gives eligible students $700 to $2,800 per year for a total of two years through spring 2024. Students can also receive aid through through the federal Pell Grant and other scholarships and grant programs.

The General Assembly also provided $107.2 million in tuition waivers to 203,365 students in fiscal year 2021-22. The largest share of waivers went to Career and College Promise ($64.5 million to 75,000 high school students), law enforcement agencies ($13 million to 39,000 students), and volunteer fire departments ($9.9 million to 24,000 students).

Established in 2011, Career and College Promise (CCP) allows high school students to earn college credits tuition-free that “lead to a certificate, diploma, or degree as well as provide entry-level jobs skills.” CCP includes early colleges, or Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS).

A 2023 draft report to the General Assembly shows almost 70,000 high school students participated in CCP during the 2021-22 academic year. CIHS accounted for 31% of CCP’s total population. The remaining 69% enrolled in College Transfer or Career and Technical Education pathways.

“What struck me is that even in some of the places that are generally growing a little quicker, the overall enrollment at the colleges has been either flat or declining across the system as a whole in terms of headcount,” Bailey said. “One area that has been growing, though, in terms of community college enrollment for the most part, has been with our Career & College Promise students.”

Related reading

Funding overview

The vast majority of funding for the state’s 58 community colleges, roughly $1.3 billion, comes from state appropriations. Around $315 million comes from tuition and fees, and nearly $294 million from local county boards of commissioners. Only $27.6 million comes from federal sources.

In the most recent budget, the state appropriated about $1.36 billion for community colleges, compared to $11.29 billion for public schools and $3.84 billion for the UNC System. That’s just 8% of the total $16.48 billion in education appropriations. While there have been increases in state appropriations since 2010, they have not kept up with inflation.

State funding is broken into three categories:

- Instructional: Based on number of FTEs and type of course ($898 million).

- Institutional and Academic Support: Campuses are provided a base allotment but can receive additional funds for additional FTEs and multi-campus centers ($528 million).

- Performance-based Allocation: Determined by student success on performance measures ($18 million).

The majority of state funding falls into the instructional category and is distributed using a formula based on full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment. One FTE is equivalent to 512 hours of instruction. Colleges are funded in arrears, meaning they receive funding based on the higher of the current year’s FTE or an average of the previous two years.

NCCCS leaders say this model prevents colleges from pivoting to proactively meet student and industry needs. For example, the model makes adding workforce programs with high startup costs a challenge. At the same time, such programs are in high demand across the state.

“We’re getting dangerously close to over-promising and under-delivering,” Cleveland Community College President Jason Hurst told the State Board of Community Colleges at its February meeting. Hurst also chairs the legislative committee of the North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents (NCACCP).

“If we do not beef up our community colleges with the skills that we can provide, we’re going to be bringing companies here that we cannot provide a skilled workforce for,” he said.

Overall budgeted FTE has decreased by 30,000 since 2010-11, according to Bailey’s presentation. Only Career and Technical Education (CTE) and workforce courses have seen an increase in budgeted FTE during that time, with an increase of 6,000.

Across the state’s 58 colleges, the vast majority have seen FTE declines since then. Only seven colleges saw increases. As a result of this decline, last year’s budget cut community college funding by a little more than $12 million.

Tier funding

While the state allocates funding to each college based on FTE, certain courses receive more state funds than others based on a four-tiered funding model.

- Tier IA: Includes curriculum budget FTE in health care and technical education courses that train North Carolinians for immediate employment in priority occupations that have documented skills gaps and pay higher wages. This tier also includes FTE in a limited number of continuing education courses that train students for the exact same third-party certification as curriculum courses in Tier 1A. ($4,889.65)

- Tier 1B: Includes curriculum budget FTE in other high cost areas of health care, technical education, lab-based science, and college-level math courses. Tier 1B also includes FTE in short-term, workforce continuing education courses that help prepare students for jobs in priority occupations and lead to competency-based industry credentials. ($4,325.46)

- Tier 2: All other curriculum budget FTE, all basic skills budget FTE, and budget FTE associated with other continuing education courses that are scheduled for 96 hours or more and are mapped to a third-party credential, certification, or industry-designed curriculum. ($3,721.27)

- Tier 3: Includes all other continuing education budget FTE. ($2,380.88)

Tier 1A is funded at a level equal to 30% higher than Tier 2. Tier 1B is funded at a level that is 15% higher than Tier 2. Finally, Tier 3 is funded at a rate that is 15% less than Tier 2.

Colleges have the flexibility to spend the funds the way each sees fit. Only basic skills and customized training funds must be spent as they are allocated.

Other funding buckets

In addition to instructional funding based on FTE, colleges receive a base allocation for institutional and academic support, which includes additional funding for multi-campus centers. They also receive a small amount of performance-based funding.

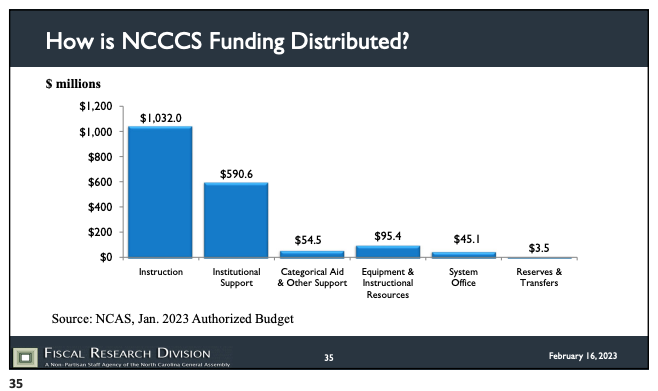

Across the system, funding is distributed in the following descending order: instruction, institutional support, equipment and instructional resources, categorical aid, the system office, and reserves and transfers. The vast majority of funding goes to instruction and institutional support.

Instruction pays for faculty salaries and instructional supplies. Institutional support pays for president, administrators, and staff salaries.

North Carolina ranks 41st in the nation for community college faculty pay, according to data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). In comparison, the state ranks 24th in faculty pay at four-year institutions.

At the Feb. 16 joint education appropriations meeting, lawmakers asked for ranked faculty pay data. One lawmaker also requested data comparing pay to median private sector earnings.

Sen. Hanig said the low pay of faculty and staff makes it difficult for community colleges to attract talent. He said lawmakers recently increased salaried pay at community colleges, and he hopes to see that continue.

“We see such a downtick or such a disparity between a community college professor versus a university professor, oftentimes we can’t fill the position, so therefore we can’t offer the class. So that also results in hurting the community colleges,” he said.

The categorical aid bucket ($54.5 million) funds specific programs like the N.C. Research Campus and child care grants. It also supports campus initiatives like the N.C. Military Business Center at Fayetteville Technical Community College, Manufacturing Solutions Center at Catawba Valley Community College, and marine technology at Cape Fear Community College.

About $94.5 million in equipment and instructional resources funds computers and other equipment needed for classes. Historically, most community colleges partner with public and private partners in order to purchase the expensive equipment required in many programs.

The $45 million in system office funding pays for staff positions, including system IT, along with student support services and economic development initiatives like ApprenticeshipNC.

What to expect for the FY 2023-25 biennium

The consensus revenue forecast for North Carolina projected an extra $3.25 billion in state revenues for FY 2022-23, bringing the revised revenue forecast to $33.76 billion.

Gov. Roy Cooper is expected to release his budget in March, after which lawmakers typically begin the formal budget-drafting process.

Enrollment declines across the NCCCS will impact the system’s funding under the state’s current budget process, Bailey told lawmakers.

At the same time, colleges will also spend the remainder of their COVID-19 relief funding and stabilization dollars this year. Such funding also includes need-based aid like the Longleaf Commitment Grant, which allows qualifying high school graduates to attend a N.C. community college free.

“We’re kind of entering this place where enrollment has not recovered from pre-pandemic, and the stabilization dollars are set to run out and be expended,” Bailey told lawmakers. “So these are some of the pressures that we see might be happening at the community college system that the General Assembly might consider.”

At the end of the meeting, lawmakers discussed how much it would cost to make aid like the Longleaf grant recurring.

“That certainly might put pressure on enrollment to the degree that this has helped certain students attend community college,” Bailey said.

In addition to a 7% salary increase for employees, the NCCCS is asking for $145.88 million in student investment in its legislative request for the biennium. The system would distribute those funds across the 58 community colleges based on a size formula and individual colleges could choose where to invest the money. NCCCS leaders said those funds will largely help expand existing programs or create new ones at each college in order to build capacity for workforce training.

“We’ve got to meet these workforce demands – thousands of jobs that are going to require some kind of postsecondary credential,” NCACCP President Dr. Jeff Cox told the State Board in February. “You all know and I know that community colleges are uniquely positioned to meet that challenge. We just need the funding to be able to do it.”

NCCCS students are currently funded at 53% of UNC System first-year and sophomore students in comparable classes, the Board’s three-year request document says, “despite smaller average class sizes and faculty credentials that meet or exceed those in the UNC System.”

The legislative request asks for an increase in the system’s recurring student FTE value to 66% of equivalent UNC courses, the document says.

“I know there’s a lot of questions about the ask and if it’s enough. We’ve got inflation that we’re dealing with – there’s a lot of issues on the table,” Hurst told the State Board in February. “But this is the most aggressive request that we’ve ever had in the history of the North Carolina Community College System. … This is not the answer to everything. But it certainly is a step in the right direction with helping meet the needs of our community colleges, the businesses and industries that we serve, and certainly looking toward the future with opportunities that are coming our way.”

EdNC will be following all education and budget updates in the long session. You can keep up with all legislative updates here, to be updated weekly. For postsecondary updates specifically, follow us on Twitter @Awake58NC.

Recommended reading