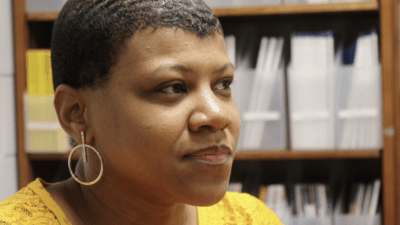

Trakeia Lynch, a Nash Community College student and parent of two, says juggling her nursing program studies with child care needs often feels like a Catch-22.

As she starts clinical rotations for her program, which Lynch said she is half-way through, her eight-month-old has nowhere to go in the morning. Lynch is expected to be at the clinic by 5:45 a.m., earlier than her infant’s daycare opens.

“I have to rely on family if they can help, friends if they can help, just whatever,” Lynch said. “As long as I make it. I can’t afford to miss clinicals.”

For parent-students at community colleges across the state, lack of child care and the cost of child care are common obstacles to returning to school and completing credentials and degrees.

Lynch receives a child care grant for her infant’s program to help cover the cost, but that support has decreased, leaving her looking for financial support from the county department of social services, where she is on a waitlist for a child care subsidy.

“I just keep moving the best way I can,” she said.

The North Carolina Community College System’s child care grant program, paid for by the state’s budget allotment, is designed to help students with this barrier. But only about 750 grants are given out each year across the state, leaving students piecing together services and funds however they can.

“We exhaust all of our funds,” said Shelly Stone-Moye, vice president of student development at Piedmont Community College. “There are students who request funds who we can’t serve because we are just tapped out.”

Stone-Moye said Piedmont gives about 10 grants to students each year at an average of $2,000 each, which sometimes doesn’t cover the full cost of child care. Each community college receives a base amount of $20,000 per year, plus an additional allocation determined by the college’s full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment. Across the system, the state has spent about $1.8 million on the program for each of the last two academic years.

Sarah Ancel, CEO of Student-Ready Strategies, said in a recent keynote at the Adult Promise Symposium that child care assistance is one of many strategies necessary to improve adult learners’ postsecondary success.

Ancel also said it’s important to not expect all financial problems to be solved within institutions, “but rather having a streamlined process, or a seamless process, for helping students with food insecurity, housing insecurity, students in need of child care, helping them connect with resources outside the institution, so that they can create sort of a basket of support to help them meet their goals.”

James Kelley, associate vice president of student services at the community college system office, estimates that the funds in the child care grant program cover about half of the need, but said it is unclear how many students do not apply or receive assistance through different resources, like the state’s child care subsidy program.

According to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services’ website, around 100,000 children receive this subsidy. More than 30,000 children, however, were on waitlists for the funds in 2019 according to the Child Care Services Association. A 2018 Center for American Progress report estimated that 44% of people in North Carolina live in child care deserts.

Student eligibility for community college grants is handled through colleges’ financial aid offices. Eligibility for the subsidy program is determined by both financial and situation criteria. Marbeth Holmes, Nash Community College’s dean of student wellness, said students in between eligibility requirements often struggle.

“A lot of times it’s those students who fall in the gaps between being eligible for federal or state services or FAFSA and not having ample income to cover the expenses of education that often do stop out,” Holmes said.

She said child care often becomes a sudden, unexpected need for students when family members aren’t available to watch children, when a partner leaves, or when a student’s schedule changes.

“Maybe they missed financial aid by $15 … and a lot of their money goes toward groceries and housing, so they come up short when there’s a need for child care unexpectedly,” Holmes said.

And the issue does not only impact student-parents with young children. Stone-Moye said before and after school care for elementary school-aged children is a big concern for students.

Kizzie Harrison, also a student at Nash, recently started an internship that is required to finish her culinary arts degree. She planned her class schedule around the school day of her two daughters, who are 10 and 11 years old.

But her internship hours at Tarboro Brewing Company West are from 3 to 10 p.m. Harrison heard about child care grants earlier in the school year but found all the funds had been used and was told that there might be funding if another parent dropped out. She tried different community resources but found they were either limited to young children or did not provide services late enough into the evening.

“I exhausted every means that they sent me,” Harrison said. “That just puts me in a position where I have to use the money I’m making from my internship to pay for child care.”

Harrison worked out a discounted price for her two daughters at a daycare that runs late into the night, but still pays $170 per week.

She said she is now the only parent in her graduating class, and that one of her close friends had to recently drop out because of financial needs related to child care.

Harrison said she is grateful that she was able to find a paid internship and has a support network that has helped her out along her educational journey.

“To have no assistance is hard, but I just have to do what I have to do,” Harrison said. “A lot of people wouldn’t be able to handle that and that’s the sad part. You may not be able to finish because of that.”