Share this story

- “To understand how we can advance equity and enhance economic mobility begins with understanding and embracing the communities we serve,” Alamo Colleges District Chancellor Mike Flores said at the 2022 Dallas Herring Lecture. #DHL2022

- “Although our population is diverse and growing, we have to ensure those residents and future generations see themselves on all our college campuses,” said Dr. Mike Flores, chancellor of @AlamoColleges1, during this year’s Dallas Herring Lecture. #DHL2022

- Colleges should view poverty as their competition, @AlamoColleges1 chancellor Mike Flores said, not other colleges. “We have to look at who we serve, and what do they look like? What are some of the challenges that they confront?” #DHL2022

|

|

Community colleges have the power to advance equity and economic mobility through local collaboration, Chancellor of the Alamo Colleges District Dr. Mike Flores told guests during the keynote address of the 2022 Dallas Herring Lecture on Tuesday.

“To understand how we can advance equity and enhance economic mobility begins with understanding and embracing the communities we serve,” Flores said. “We’re creating leaders one person at a time – we’re changing our communities.”

The Alamo Colleges District is a network of five community colleges in San Antonio and Universal City, Texas, and serves the Greater San Antonio metropolitan area. The district is the largest provider of higher education in South Texas, serving about 100,000 students, Flores said, and more than 80% are students of color.

National community college leaders like Flores have delivered the Dallas Herring Lecture since 2015. The lecture honors the late W. Dallas Herring – the “father” of the N.C. Community College System (NCCCS) – and is hosted by North Carolina State University’s College of Education and the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research.

“Throughout his life’s work, Herring was guided by his vision that education should be an ‘opportunity for all the people.’ Like Herring, Flores’ vision is to create a system that is accessible to all, and we are incredibly honored to have him as this year’s Dallas Herring Lecture speaker.”

— Dr. Audrey J. Jaeger, executive director of the Belk Center

Along with Herring’s many education contributions in North Carolina, Jaeger also acknowledged his complicated legacy. She noted his “troubling views” regarding segregation and integration early in his career and his willingness to acknowledge and learn from mistakes.

“So while Herring’s accomplishments are many, and his advocacy inspiring, he was not without flaws,” Jaeger said. “It is relevant for us to guard against the tendency to put our leaders on the pedestal. Instead, we ought to recognize their achievements, celebrate their successes, and learn from their mistakes. … Through many, not one, we will continue to fill the gaps to access, break down barriers to success, and transform lives and communities across the state. Together, we will carry this legacy forward.”

Bottom: Attendees at the Dallas Herring Lecture. Hannah McClellan/EducationNC

During his keynote speech, Flores offered a framework of meeting diverse student needs using local collective impact strategies.

Flores spoke of his firsthand knowledge of the economic mobility education can provide. As the child of migrant farmworkers, he saw his parents –Ruben and Acente Flores – “overcome the odds” to earn college degrees. His father eventually became a dean at San Antonio College – one of the five colleges in the Alamo Colleges District – and dreamed of his son becoming the first Hispanic Chancellor there. Flores achieved that goal in 2018 and has dedicated his career to ensuring an equitable and accessible education for all students.

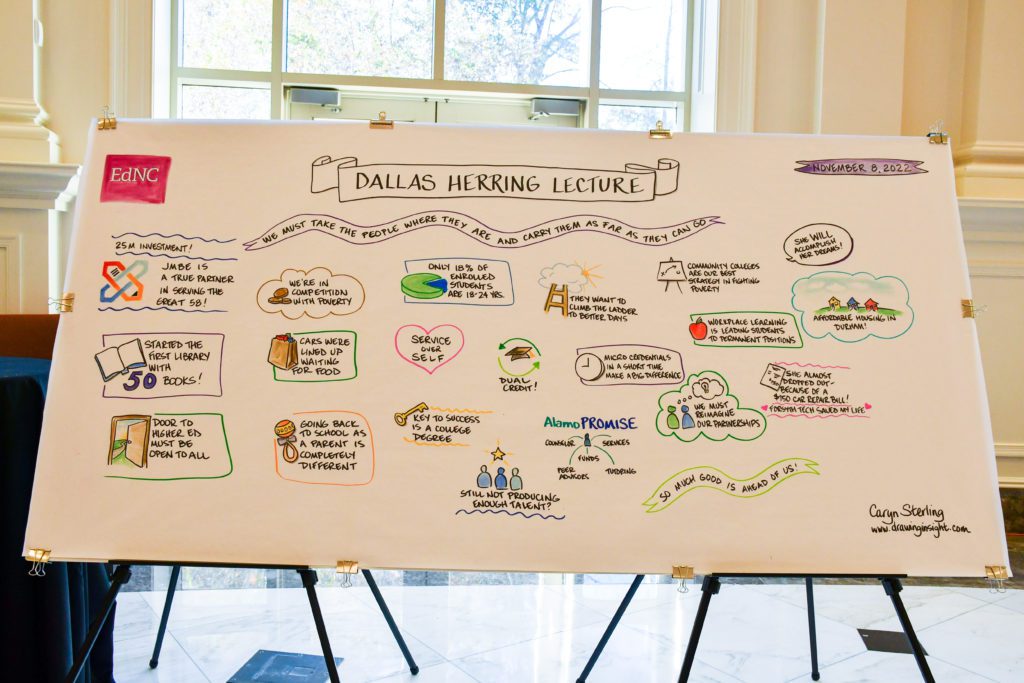

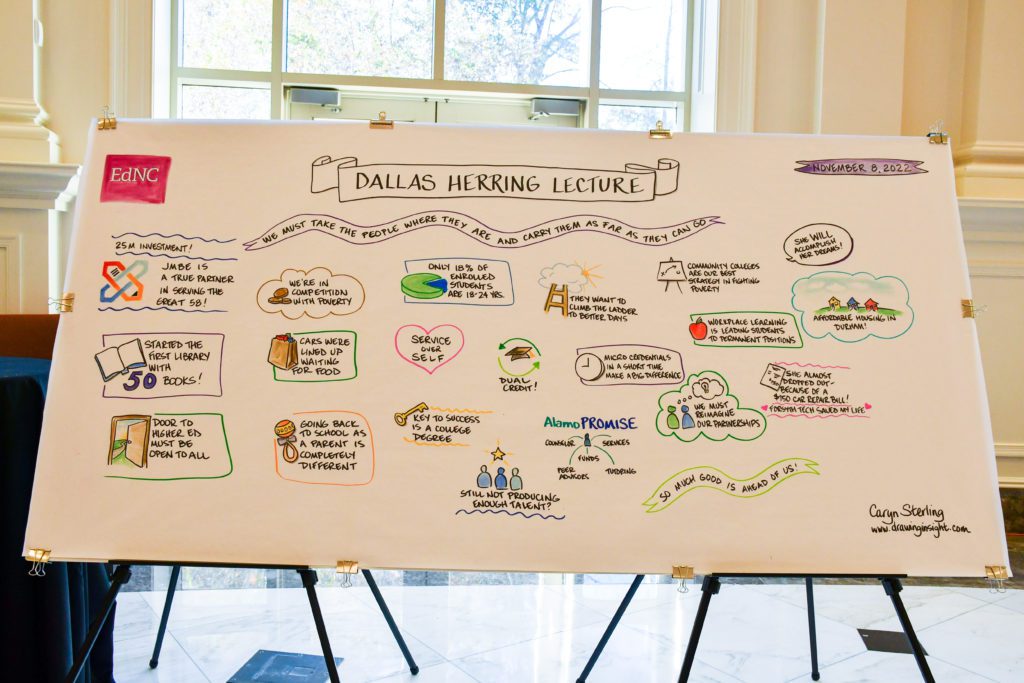

Flores quoted Herring’s words, spoken to the North Carolina legislature in 1966, as a foundation for his framework: “We must take the people where they are and carry them as far as they can go …”

He offered six steps to the framework he called a “cycle of transformation.”

Understanding and embracing the communities we serve

This work must start with knowing your community, Flores said.

Of the Alamos Colleges District’s approximately 100,000 students, more than 68% attend part-time, Flores said, and 70% rely on some type of financial aid. One out of every five Alamo students (21%) are parents.

“Although our population is diverse and growing,” he said, “we have to ensure those residents and future generations see themselves on all our college campuses.”

The district’s colleges serve many Hispanic, Black, and low-income students. Helping these students see the value of investing in postsecondary education is important, Flores said, and requires a collaborative posture instead of a competitive one.

Nationally, total full-time student enrollment declined by nearly 20% at community colleges since spring 2020, according to the latest report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. In North Carolina, overall community college enrollment declined 11% in fall 2020 compared to fall 2019. While some colleges have seen growth since then, many are not back to their pre-pandemic numbers.

Enrollment matters because it shows how a college is reaching more students, Flores said. And during the pandemic, Black, Brown, and low-income students were disproportionately impacted by enrollment and attainment declines. In North Carolina, for example, Black men suffered the largest enrollment decline in 2020, with traditional degree-seeking enrollment falling 14% from the year prior for this group.

“The past few years has provided challenges for each and every one of us,” Flores said.

But colleges should view poverty as their competition, not other colleges, he said.

“We have to look at who we serve, and what do they look like?” he said. “What are some of the challenges that they confront?”

Flores also highlighted how postsecondary degrees increase earning potential.

A recent U.S. Census Bureau report examined the dynamics of poverty between 2017 and 2019. Some of the largest differences in poverty were among those with different levels of education, according to the report. The report concluded that adults aged 25 and older with no high school diploma were over three times more likely than those with a bachelor’s degree to experience episodic poverty and 19 times more likely to experience chronic poverty.

Making sure all the people in a community can access educational opportunities is a vital role for community colleges, Flores said.

Embracing the power of HSIs and MSIs

One way colleges can serve their communities is by investing in Hispanic/Minority Serving Institutions (HSIs and MSIs).

HSIs are “accredited, degree-granting, public or private nonprofit institutions of higher education with 25% or more total undergraduate Hispanic full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment, which also have an enrollment of low-income students and low average educational and general expenditures per FTE student, compared to similar institutions.”

— The Higher Education Opportunity Act, Title V, 2008

2020 census data show “a changing face of America,” Flores said. The U.S. has increased in ethnic and racial diversity, with more than 40% of the population identifying as one or more racial and ethnic groups.

Thirteen states now have Hispanic or Latinx populations of more than 1 million, Flores said, including North Carolina. In the last decade, nearly 320,000 Hispanic or Latinx individuals became North Carolinians – the largest numeric increase in the state by any racial or ethnic group.

For community colleges, the HSI and MSI designation can help provide more intensive and intentional college and career advising, Flores said, along with wraparound student support services and affordable learning pathways.

“Most importantly,” Flores said, it can help “to better align services for increasingly diverse populations.”

In academic year 2020-2021, 559 institutions met the federal criterion for HSIs with 2.2 million undergraduate Hispanic students. Of those, 40%, or 226 institutions, are public two-year colleges.

North Carolina does not house any HSIs, but nine colleges are quickly approaching the HSI threshold, according to a list of “emerging” HSIs by national advocacy group Excelencia in Education. All of those schools are community colleges with the exception of Salem College.

At the Alamo Colleges District, all five community colleges are HSIs, and one is both an HSI and a historically Black college and university. Such designations provide access to additional resources and learning networks to better meet the needs of our diverse populations, Flores said.

Student success stories at such institutions show the power education can have against generational poverty. Colleges must disaggregate data and then prioritize outcomes for students who are underserved, Flores said.

“These are students at Alamo Colleges who look like me, they look like my daughters – they are students who in many cases are the first ones to go to college and earn a degree,” Flores said. “It is critical that we prioritize our funds for those who are under-resourced or don’t see themselves on our campuses, or don’t feel that they have a voice.”

Prioritizing outcomes for our most marginalized communities

While 39% of white community college students graduated between the academic years 2019 and 2021, only 28% of Black students graduated during that same time period, according to a 2022 report from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

The recommended actions toward equity outlined in that report align with the Alamo Colleges District vision, Flores said.

- Improve access to basic needs/holistic support for students, inclusive of child care access.

- Strengthen transfer pathways.

- Evaluate community college outcomes by race.

- Provide a pathway for free community college.

In 2015, the state of Texas launched a strategic plan aiming for at least 60% of Texans ages 25-34 to achieve a postsecondary degree by 2030.

North Carolina’s educational attainment goal is for 2 million North Carolinians ages 25 to 44 with a meaningful, high-quality credential or postsecondary degree by 2030. That’s about 67% of adults in that age bracket, according to projections from Carolina Demography.

More than 39 million adults in the U.S. have at least some college credit and no degree or credential, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. There are slightly more than 1 million North Carolina adults with some college but no degree or credential as of July 2020. Nearly 34% of those adults are younger than 35 and about 54% are ages 35 to 64.

Recently, Flores said the Texas strategic plan was updated to more directly include adult learners and students of color, which he said is crucial for success. Recent initiatives in North Carolina to reach adult learners, like N.C. Reconnect and Project Kitty Hawk, back up that claim.

“And you definitely don’t operate in isolation,” Flores said, regarding the need for partnerships. “To ensure that we don’t remain impoverished in the United States, we have to be able to create these pathways for our students.”

Creating diverse pathways for students

Community colleges must offer a variety of pathways to meet multiple types of students, Flores said.

Expanding dual credit options is one way to do that. The Alamo Colleges District is the largest provider of dual credit programs in its region, Flores said, allowing students to graduate with a two-year degree and high school diploma. The Alamo Colleges District is working to ensure students can easily transfer their dual credits without losing them.

In North Carolina, high school students can access free college courses through Career and College Promise (CCP). CCP students can choose from the following pathways: college transfer, career and technical education (CTE), and Cooperative Innovative High Schools. In 2020-2021, there were 58,727 public high school students enrolled in college courses while in high school, according to a 2022 CCP legislative report.

The Alamo Colleges District has also partnered to improve its dual credit offerings and resources. One example, Diplomás, includes 23 cross-sector partners focused on increasing college attainment for Hispanic youth.

The District organized its 350 degree and certificate programs into six career clusters called the AlamoINSTITUTES. These institutes align with K-12 and industry, “and provide a starting point for students, enrollment coaches, and assigned advisors to identify a career interest and create a tailored individual pathway for each and every one of our students.”

One reason dual credit programs are so important is because of their affordability.

The costs for a college education have doubled in the last 30 years, Flores said, with the average annual cost for tuition and fees at a community college at almost $4,000. Notably, that estimate does not account for housing, food, child care, transportation, books, and health care.

“This is where our College Promise program comes into play. We’ve been able to to ensure that we provide access to each and every student within our community.”

— Dr. Mike Flores

The district launched AlamoPROMISE in fall 2019 under Flores’s leadership in partnership with city and county leaders, the business community, independent school districts, nonprofit organizations, and community members. Graduating seniors from 50 area high schools, most of which are in low-income areas, are eligible for tuition-free assistance. AlamoPROMISE Scholars also have access to wraparound services like free food and clothing, low-cost child care and health care, and emergency financial aid for things like rent and car payments.

More than 400 Promise programs exist throughout the country, Flores said, including in North Carolina.

Eligible N.C. students can apply for the Longleaf Commitment Grant — providing $700 to $2,800 per year, for a total of two years — just by filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and enrolling in one of the state’s 58 community colleges. And as of November 2020, 19 North Carolina community colleges had some form of local promise program that gives scholarships to eligible students in their service areas.

Last year, the Alamo Colleges District graduated the inaugural cohort, and 10,000 students “saved” their seat to be an AlamoScholar – a new record. About 82% of Promise Scholars are students of color, Flores said.

“The other part of it is the opportunity dynamic,” Flores said. “It (AlamoPROMISE) takes the opportunity cost of work and family responsibilities off the table for many of them.”

Providing holistic student support

The Alamo Colleges District established AlamoADVISE in 2014 to help high student transfer rates and completion times.

The case-management program allows students to formalize an academic plan with certified advisors. Students then create a mission statement and meet at 15, 30, and 45-hour touchpoints. Advisors are trained in holistic advising to support individual student needs.

The colleges also created Transfer Advising Guides (TAGS) to help students save time and money by accessing clear pathways. About 75% of Alamo Colleges’ students transfer to a four-year university upon completion of their associate degree, Flores said. That’s compared to about 30% of community college students nationally. On average, those students lose more than 40% of their credits, forcing them to spend more time and money to repeat courses.

In September, the UNC System announced a new database to help community college students transfer across North Carolina public institutions more easily. The online database, called the UNC Common Numbering System, includes over 1,600 undergraduate, lower-level courses from institutions within both the UNC and North Carolina Community College systems.

Alamo Colleges developed on-campus advocacy centers at each of its five campuses after a student survey reflected housing, food, and mental health needs. The centers partner with several local nonprofits to meet student needs, including mental health care. In North Carolina, many community college leaders are promoting similar “one-stop centers” to help meet student needs in one place.

Before the start of the pandemic, the Alamo Colleges District also launched a student helpline to answer any requests for advocacy assistance and emergency aid. During the 2021-2022 academic year, the advocacy center helpline fielded more than 9,200 calls.

The Alamo Colleges District also established pop-up markets with healthy food for students in collaboration with the San Antonio Food Bank. In partnership with the local medical school, UT Health San Antonio, students can also access primary health care through Wellness 360 centers at little to no cost. Wellness 360 started primarily as a telehealth service and expanded its onsite offerings in the last year.

“It’s critical that we provide holistic student support,” Flores said.

Reengaging those individuals left behind

Finally, colleges must serve students left behind by traditional education models.

Short-term training and micro-credentials are one solution, Flores said.

Alamo Colleges also use Talent Pipeline Management (TPM), a strategic framework developed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, to help engage people in higher paying, in-demand jobs. The TPM framework helps create strategic alignment between schools and industry to support students in their transition to the workforce. North Carolina is one of the states using TPM, through the North Carolina Chamber Foundation.

Helping adults complete their high school degree is another way to meet all students. In the San Antonio metro area, nearly 200,000 individuals lack a high school diploma or equivalency, he said. The Alamo Colleges District helps provide high school equivalency support as part of its city workforce recovery program.

Initially, the goal was to help those students complete their high school diploma and then enter a short-term training program. Since then, many students enrolled in longer-term programs.

Flores urged attendees to see student success stories as inspiration and motivation for their work. Students want better lives for themselves and their families, he said, and community colleges help provide those opportunities.

“We have the ability to transform their lives,” he said. “I think we have a clarity and call to be able do more, to do better, to challenge each other and have conversations about what it means to prepare a new generation of leaders to follow in our footsteps.”

Dr. Janet Spriggs, president of Forsyth Technical Community College and this year’s featured respondent for the 2022 Dallas Herring Lecture, highlighted models being implemented in North Carolina’s community colleges to advance equity.

As a low-income, first-generation student herself, Spriggs testified to the power of education.

“I hope that my story and the other stories you’ve heard serve as exemplar personal examples of the power of education to transform not just one life, but generations of lives,” she said. “Now is the best time for community colleges to courageously challenge the status quo and lead the work of creating a more equitable future for each and every North Carolinian.”