In April, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. turned the focus of his Make America Healthy Again movement toward school food, promising “major, dramatic changes” in school nutrition programs, which serve nearly 30 million students across the country each year.

“School lunch programs have deteriorated where about 70% of the food that our children eat is ultraprocessed food, which is killing them,” Kennedy said during an April event. “We need to stop poisoning our kids and making sure that Americans are once again the healthiest kids on the planet.”

The federal government is working to develop a uniform definition of ultraprocessed foods, but they are generally considered to be industrially produced, ready-to-eat foods that contain high levels of sugar, salt, or additives, such as chips, soft drinks, and frozen meals.

Global consumption of ultraprocessed foods has increased rapidly in recent years. In survey results published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in August, youth ages 18 and under consumed more than 60% of their daily calories from ultraprocessed foods.

Now, there is a growing body of research associating ultraprocessed foods with negative health outcomes. In November, a three-part series published in The Lancet found evidence that increased consumption of ultraprocessed food is a “key driver” of escalating rates of diet-related chronic disease. The series authors urge governments to take action to reduce the consumption of ultraprocessed foods, including by restricting ultraprocessed foods in school meals.

Federal efforts to improve the nutritional quality of school meals have largely focused on implementing stricter nutrition standards, which regulate nutrients like added sugars and sodium. However, these regulations don’t necessarily result in less ultraprocessed food — instead, manufacturers often reformulate their products to meet new thresholds. School nutrition programs, faced with tight budgets and limited staff capacity, often rely on ultraprocessed products like frozen pizzas, packaged sandwiches, and packaged breakfast pastries.

As the federal government and other entities work to reduce the consumption of ultraprocessed food, what will it actually take for schools to stop serving them?

“Our government right now has … more of a ‘takeaway’ mentality,” said Jayme Robertson, school nutrition director for Yadkin County and Elkin City schools, regarding federal school nutrition standards. “If you change that and instead focus on more fresh, more local, more raw ingredients, more scratch cooking, then that’s where the real impact is going to happen.”

Robertson and other national nutrition researchers believe a paradigm shift is needed for schools to reduce ultraprocessed food and implement more scratch cooking, which involves preparing meals with whole, raw, or minimally processed ingredients. While data on the prevalence of scratch cooking is limited, the latest USDA Farm to School Census found that most school nutrition programs make less than 25% of meals from scratch.

“We need to stop penny pinching and start looking at the long-term outcomes of what serving less processed food in schools would produce. And we need to make sure our school districts have the resources they need to actually do this,” said Mara Fleishman, CEO of the Chef Ann Foundation. “If we want Americans to stop eating ultraprocessed food, let’s start in kindergarten.”

Read more about school meals

The technical challenges of scratch cooking

Before scratch cooking can begin, school nutrition programs have to secure necessary equipment, hire staff with culinary expertise, purchase ingredients, and plan menus that meet federal requirements.

Equipment

“When you go into schools that don’t have running water, don’t tell me to scratch cook,” said Dr. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance.

Many school nutrition programs cannot scratch cook due to limited or outdated kitchen facilities that prevent the storage, processing, or cooking of whole ingredients — such as a lack of coolers or freezers to store fresh ingredients.

Buying new equipment or renovating facilities can pose a major cost. School nutrition programs operate financially independently of school districts as self-sustaining, nonprofit enterprises. The roughly $4.60 per lunch provided by federal reimbursements must be used to cover the cost of food, supplies, labor, equipment, and overhead costs, often leaving little room in the budget for large capital investments.

Even if a district can afford the upgrades needed to scratch cook, there may be additional hurdles to installing and using that equipment, particularly in older school buildings. For example, Wilson recalled speaking to a school nutrition director who spent $500,000 on equipment that hasn’t been used yet because there isn’t enough power in the school building to plug it in.

Staffing

School nutrition programs often face challenges recruiting and retaining staff. In a national survey of school nutrition directors conducted by the School Nutrition Association (SNA) in 2024, nearly 89% of respondents reported challenges with staff shortages, and the overall vacancy rate was 8.7%.

To scratch cook, school nutrition programs not only need sufficient staffing levels — they also need to hire staff with the skills necessary to cook using whole ingredients, including knowledge of specific culinary skills, food safety, and equipment use. According to Wilson, the majority of school nutrition employees are not paid to attend training, making it difficult for them to build the skills needed to scratch cook.

“It’s about valuing food — valuing what they contribute to the school day and to the students’ life. We don’t value them, and that’s why they’re many times the lowest paid,” said Wilson of school nutrition professionals compared to other school employees.

Ingredients

School nutrition programs often need to purchase more fresh, whole ingredients to scratch cook, which may involve developing new vendor relationships and executing new contracts. But this is not as simple as finding a local farmer to purchase meat and vegetables from, according to school nutrition leaders.

As recipients of federal funding, school nutrition departments must adhere to a variety of federal procurement regulations, which dictate what procurement techniques can be used based on the purchase amount.

According to Wilson, varying interpretations of federal procurement rules are one of the biggest challenges facing school food purchasing. This challenge is further compounded by the fact that, if a state or locality has different purchasing thresholds than the federal government, the more restrictive threshold must be followed.

“If everybody would get on the same page and just follow the federal standard rules, we could work at changing some of those federal rules to make them better for fresh, whole food,” she said.

Menu plans

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulates the nutritional quality of school meals through meal patterns, which dictate each required component of the meal — such as how many cups of different types of vegetables must be included — and place limits on calories, saturated fat, added sugar, and sodium.

Scratch cooking involves preparing recipes that rely on whole ingredients but still adhere to these requirements, which takes more planning and results in greater variation than purchasing pre-made, ultraprocessed items that already meet all requirements. If schools deviate from the meal pattern, they risk not receiving federal reimbursement.

“We have forced, particularly small districts … where they don’t have the money or the team to hire chefs or all these other people to help them with this — we’ve forced them to buy pre-packaged, formulated food, because it guarantees they meet the meal pattern,” said Wilson.

Wilson recalled that, during her time as a school nutrition director, scratch-made zucchini muffins were less than 0.1 ounces away from the required weight, disqualifying the muffins from counting as a meal component that day.

“You can’t do scratch cooking if that’s what you’re under when it comes to the micromanagement of the meal pattern,” she said.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

The adaptive challenges of scratch cooking

Beyond the technical challenges facing scratch cooking, shifting away from ultraprocessed food and toward preparing meals from scratch requires change management. This presents a series of adaptive challenges, or those related to shifting mindsets, values, and culture.

Through her work at the Chef Ann Foundation, which supports schools in implementing scratch cooking, Fleishman has seen that a strong commitment from school nutrition leaders is crucial to success — because scratch cooking isn’t easy.

“In many ways, it’s easier to pull a frozen chicken nugget out of the freezer,” she said. “When you start building a scratch cook program, there is a lot of uplifting that has to be done. So you really need to be in it, you have to see the value of it, you have to believe in it, you have to be in it for the long term.”

The Chef Ann Foundation “sees the transition to scratch cooking as a continuum of gradual progress rather than an all-or-nothing approach,” according to its website, with a five-step continuum that ranges from ready-to-eat meals to scratch-made meals.

Fleishman said that moving along this continuum takes time, and schools often have to start small and introduce new scratch-made menu items gradually as they secure new equipment.

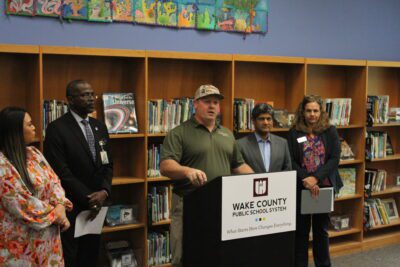

As Yadkin County and Elkin City schools transitioned to scratch cooking over the last five years, Robertson said she has worked intentionally to build trust and buy-in with her school nutrition team. In her first year as school nutrition director, she worked in school kitchens to build relationships, learn about the speed-scratch approach, and understand equipment and staffing levels.

“It really made sense for me to use that first year to observe, to learn, to really immerse myself in how the program was operating, instead of coming in and just making drastic changes,” said Robertson.

Using lessons from that experience, she then created a menu committee and a managers council to ensure “boots on the ground” voices informed the district’s approach to scratch cooking. She said this created a structured way to gather feedback and troubleshoot plans before they were implemented.

“It gave everybody a voice at the table, and it got everybody on the same page in terms of the direction we were moving,” she said.

School nutrition staff then participated in professional development where they watched new scratch-made recipes be prepared, providing them with a visual, step-by-step explanation of how to cook each component. Just like cooking at home, Robertson said that as staff cooked new recipes repeatedly, their comfort level grew.

Fleishman echoed how important creating buy-in with school nutrition professionals is for the success of scratch cooking efforts.

“If you’re able to build a culture of professionalism and value within school food and help your team understand why cooking from scratch is so important and what the impact of their work will be, then you don’t necessarily get some of the pushback that you see,” she said.

Then, once scratch-cooked items are available, there’s still work needed to shift students’ preferences away from the ultraprocessed foods they may be accustomed to eating.

“It’s not like they’re serving packaged, processed french toast sticks, and then you put the scratch-cooked french toast casserole on the menu and everyone’s like, ‘Yeah I like this so much better,’” said Fleishman. “Ultraprocessed food is highly addictive. So there is a period of transition.”

Marketing to students and families that explains what scratch cooking is, why the school nutrition program is doing it, and why scratch-made items are healthier can help encourage students to try new items.

For example, Robertson shares new recipes through newsletters and on social media, highlighting which ingredients are locally sourced and tagging farmers. She also uses taste tests with students to ensure scratch-made items are things they enjoy eating.

The financial equation

While there’s a common perception that scratch cooking is more expensive than serving processed food, according to Fleishman, it doesn’t necessarily have to cost more. Although equipment purchases can pose a major cost, when comparing a scratch-made item directly with a processed counterpart, the scratch-made item may be less expensive or cost the same, depending on what ingredients are used.

“In reality, it could cost more — you could buy all organic, regenerative ingredients. But it doesn’t have to. You can scratch cook within the federal reimbursement rate,” said Fleishman, adding that it’s crucial for school nutrition directors to have strong financial management skills in order to manage a sustainable scratch cooking program.

For example, in Yadkin County and Elkin City schools, Robertson said it costs roughly $1.10 per serving of the pre-made spaghetti sauce the district previously purchased, and it now costs $0.95 per serving to prepare a scratch-made sauce. In an evaluation of four school districts that participated in the Chef Ann Foundation’s Get Schools Cooking program, the “overall financial health” of school food programs increased after transitioning to scratch cooking.

Robertson has also leveraged strategic menu planning to purchase a core set of ingredients and cut down on unnecessary inventory. For example, she now purchases raw ground beef as a base protein for multiple scratch-made items — including spaghetti, tacos, and hamburgers — replacing several processed items.

What’s needed to support more scratch cooking?

Robertson compares trying to implement scratch cooking in the current policy and regulatory environment as “putting together a Jenga puzzle and hoping it doesn’t fall.”

“You’re asking employees that you’re not paying hardly anything to, to see these regulations through and provide an enjoyable experience. I feel like it’s just becoming harder and harder. It’s almost like you’re being asked to do more with less every single year,” she said.

As more schools work to reduce ultraprocessed foods in school meals and implement scratch cooking, experts point to a variety of possible solutions.

Higher school meal reimbursement rates

As the costs of food and labor continue to rise, many school nutrition programs find it difficult to provide school meals within the per-meal federal reimbursement rate, which is roughly $4.60 for each free school lunch and $2.46 for each free school breakfast, with lower reimbursements for reduced-price and paid meals.

“I do not feel like students thrive on mini powdered donuts … but I know the mini powdered donut is more cost-effective, and it takes me less labor in the morning, and I don’t have the money to put into it,” said Robertson.

In the 2024 SNA survey of school nutrition directors nationwide, nearly all respondents cited challenges with the cost of food (97.9%), labor (94.9%), and equipment (91.4%), and only 20.5% reported the reimbursement rate is sufficient to cover the cost of producing a meal.

Low reimbursement rates can also make it difficult for school nutrition programs to recruit and retain staff. This is particularly true in areas with a higher cost of living where other food service jobs may pay employees a higher wage, making it difficult for school nutrition programs to offer a competitive wage.

Introduced in Congress in October, the Healthy Meals Help Kids Learn Act of 2025 would permanently increase the federal reimbursement rate for school meals, adding an additional 45 cents for each lunch served and an additional 28 centers for each breakfast served.

“High costs and insufficient funds are hampering efforts to expand scratch cooking and reduce added sugar and sodium in school meals,” said SNA President Stephanie Dillard in a press release about the bill. “School meal programs desperately need increased reimbursements to invest in staff and training, upgrade kitchen equipment, and purchase more fresh and local produce.”

Funding for school kitchen equipment

Because school nutrition programs operate financially independently, local school districts often aren’t able to fund equipment for school kitchens. This means state or federal investments are needed to ensure schools have the equipment needed to scratch cook.

In previous years, the USDA has offered equipment assistance grants, but funds can only be used to cover the cost of the equipment and not the corresponding increase in energy or other utilities needed to use it, which Wilson said poses a challenge.

At the state level, California has allocated more than $700 million from the state’s general fund to provide funding for infrastructure upgrades and equipment in school kitchens, along with staff training, with the goal of helping more schools offer scratch-made items.

Investments in the school nutrition workforce

Investments are also needed to better recruit and train culinary professionals to work in school nutrition programs, school nutrition leaders said.

“Unless we are able to fundamentally look at developing the greater workforce in school food, then a lot of the work that we’re all doing is kind of pushing this boulder up a hill, and it might come back down,” said Fleishman.

To help meet these workforce needs, the Chef Ann Foundation developed the nation’s first registered apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship program for scratch-cooked school meals, currently available in Colorado, Virginia, and California, with more states to come. The apprenticeship programs provide aspiring and beginning school food professionals with the skills needed to create and manage scratch-cook school meal programs.

Adopting universal free school meals

Serving free meals to all students increases student participation in school meals — along with many other benefits — providing school nutrition programs with more federal reimbursement funds and giving them a better opportunity to enhance the food they are serving, including through scratch cooking.

Currently, nine states — California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Vermont — have passed permanent legislation that provides free school meals to all students. Dozens of other states, including North Carolina, have introduced bills that would do the same.

Read more about school meals for all

Funding for local food purchases

Given that scratch cooking requires school nutrition programs to use whole, raw, or minimally processed ingredients, funds to purchase local food for school meals can help offset the costs of scratch cooking while keeping school food spending in the local economy.

However, in March 2025, the USDA canceled $660 million for the Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement Program. Started in 2021, the program provided funding to states to purchase local foods for use in schools, helping farmers sell more of their products to schools and expanding local and regional food markets.

Without this funding, schools face even greater challenges purchasing local food, reducing the amount spent in the local agricultural economy and relying instead on large national wholesalers or distributors.

Looking ahead

Despite the challenges of implementing scratch cooking, Robertson said the shift to preparing more items from scratch has generated strong support from the local community, which has been fulfilling for her staff.

“Staff members will get stopped in grocery stores, by parents or teachers, and they’ll rave about a particular menu item they heard their child talk about,” she said.

Robertson’s mom worked in public education, and she remembers a time when students enjoyed the food they were served in the school cafeteria. They would even ask for recipes.

“I’m not sure when that stopped, but that’s kind of my ultimate goal — to get back to that and build those relationships,” she said.

Recommended reading