Last week, I spoke with 50 superintendents from around the country about leadership before, during, and after the pandemic. The convening and conversation was organized by The Schlechty Center, “a private, nonprofit organization committed to partnering with education leaders who are interested in nurturing a culture of engagement in their organizations, with the ultimate goal of increasing profound learning for students.”

Afterwards, George Thompson with the Center emailed me and said, “You and your team have created something needed in each state.”

Education journalism is not new, and a lot of it (even some of ours) is really great journalism. But as our founder Ferrel Guillory notes, our journalism is not our raison d’être — our reason for being.

EdNC exists to prompt change for our students, our state, and our future.

Like EdNC, all of the superintendents at the convening oriented their leadership around the nexus of student learning and innovation long before the pandemic, so the concepts of change management and design thinking were not new to them.

But emerging from the pandemic provides an opportunity for reflection, and it is in the reflection that we discern how to iterate our work moving forward.

As we begin to think about which leaders, which organizations, which districts, and which community colleges thrived during the pandemic regardless of sector, here are eight lenses we are using to reflect on the work we do and the work we hope to do.

What is the mindset of the leader? Does the leader have a process for attending to their personal and professional development? Do they invest in the whole team as if each person is the CEO?

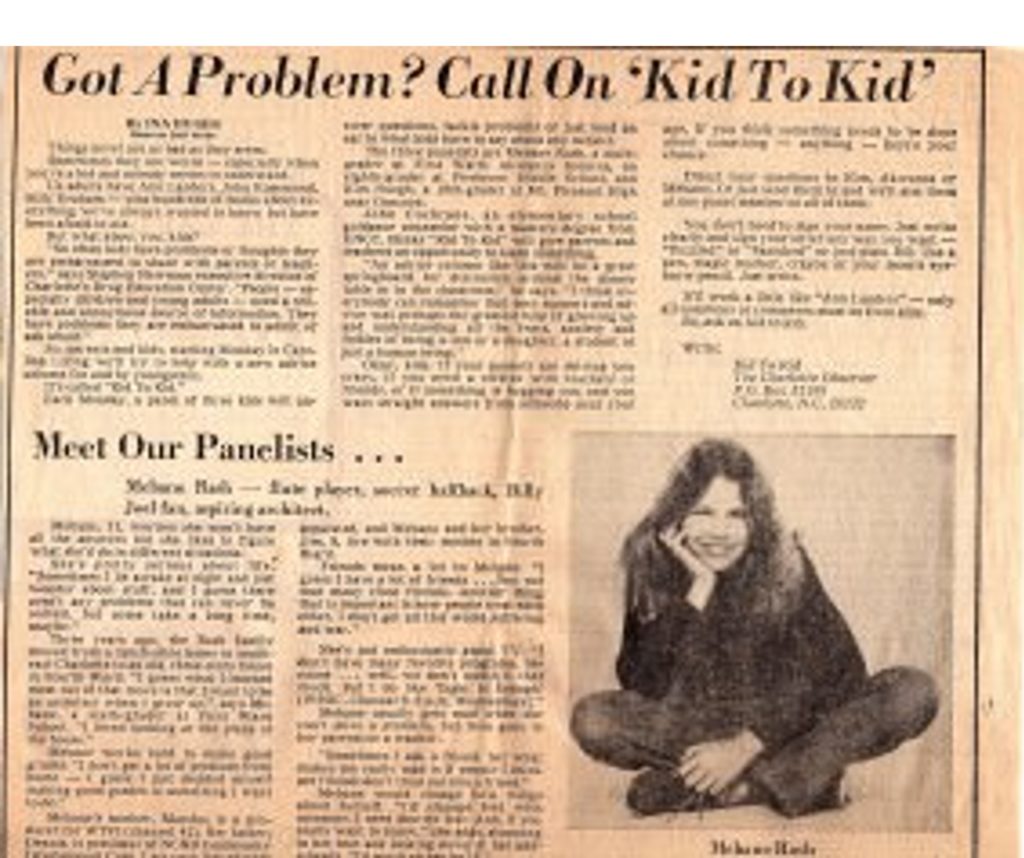

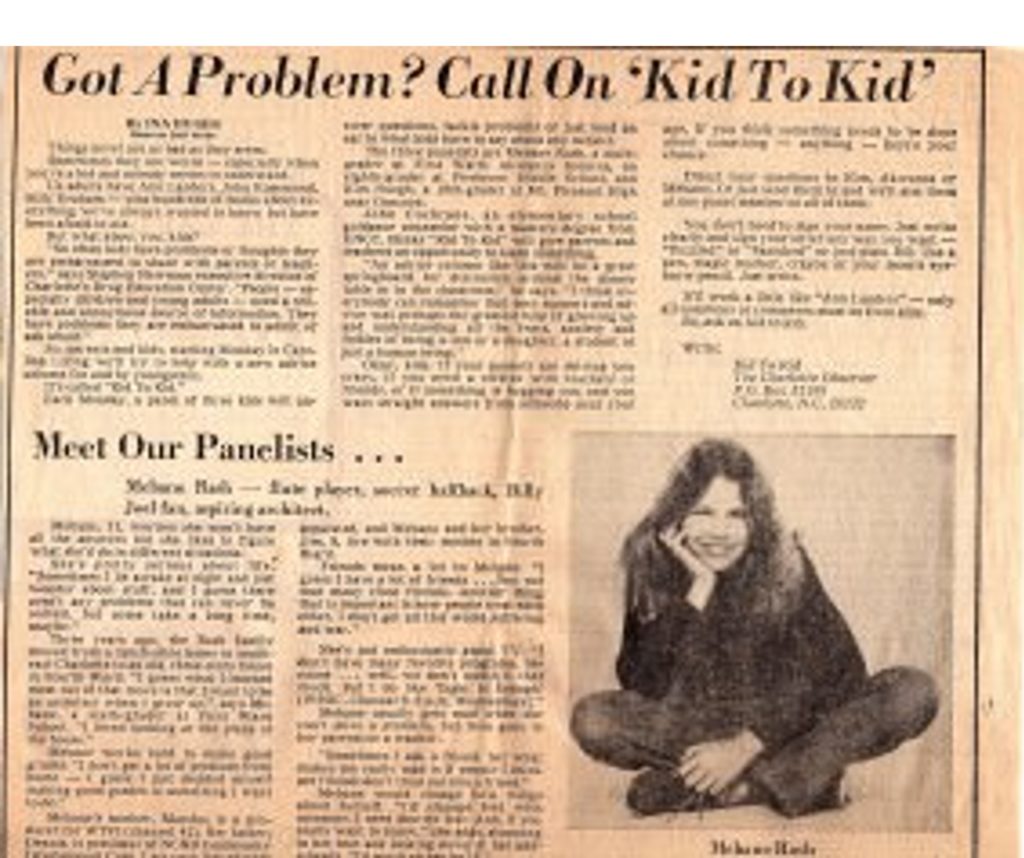

I am a lawyer, not a journalist. Before EdNC, my only experience of being a journalist was in sixth grade as a columnist for The Charlotte Observer. I contributed to a column called “Kid-to-Kid,” and the advice I offered was the worst. Even my grandparents were embarrassed.

Only about half of the EdNC team are trained journalists.

On our best days, EdNC operates as a team of peer experts. There is as little management as possible. We trust the people we hire to do their jobs with fidelity to our mission, and we trust them to manage up if they need support personally or professionally. Nothing makes me happier than when I am out in community and someone asks me if I work for Molly or Nation or someone else on our team.

On the toughest days, my title comes into play, and it is my job is to serve as CEO and editor-in-chief.

It is on us as leaders to lead, especially during times of crisis.

The world is just beginning to ask what predisposed some leaders to embracing the crisis as a window of opportunity.

From the beginning of EdNC and throughout the pandemic, it was a strategic advantage that I was not a journalist. Though for sure I could have used the training, the advantage came from not needing to preserve and build at the same time.

Alexander Russo, who analyzes education journalism, recently wrote that leaders like me are “free from the traditions and established culture” of whatever we are doing.

He is right. In building EdNC and in leading during the pandemic, all I could see is what was possible.

Superintendent Mark Garrett in McDowell County notes that leaders with this mindset tend to ask “why not?” instead of “why?”

As leaders, our framework on leadership is shaped by lived experience, our education, our job experiences, and a host of other factors. But those things don’t have to shape our leadership. Awareness can help us make choices that pivot us away from habits and patterns, optimizing our leadership for the future.

Leaders who thrive have a process to attend to their own personal and professional development, and that process can’t be static. As leaders, we need coaches and mentors and accountability partners. We need to be part of external cohorts of leaders. We need access to professional development that stretches us and makes us uncomfortable. We need a robust 360 performance review process to hold ourselves and our leadership to account. Mostly, we need to be on the ground out in community so we are constantly broadening our perspective. And we need time for reflection.

It’s not just the CEO that needs that process. It is the whole team. Invest in each of them.

Is change management and design thinking central to the work of the organization? Does the organization understand how to leverage crisis as a window of opportunity?

Building EdNC has been a very public exercise in vulnerability as our state has watched us teach ourselves to do this work.

As I was brought into the founding process, Superintendent Ed Croom, who was then-leading the Low Wealth Schools Consortium, gave me the greatest gift when he said, “fail forward, fail fast.” To me, it felt like permission to run and to run fast toward all that was possible. When we failed, and we failed often, we quickly analyzed why (quickly is the most important word here – leaders and organizations often get stuck processing after failure), and then we started running again.

We used design-do loops — where you design a process improvement, try it, iterate, and go through the process again and again — to build EdNC, and we still are always running loops to iterate our process. During the pandemic, we built out our audience playbook and we are currently working to broaden and deepen our reach in all 100 counties leveraging the organic pathways that move information.

Here is how we built our architecture of participation and used it to grow our audience by 142% during the pandemic.

Does the leader and the organization have an established process for securing buy-in?

I believe what fosters buy-in to both leadership and the work of an organization is a transparent, predictable process for aligning available resources and the aptitude of the team with the scope of work.

Our audience is given the opportunity to weigh in on the scope of work in our annual survey, which is usually circulated in November and December. They go first.

We present that information to our board and strategic council in January along with our annual report. At that point, we take their feedback into consideration.

The team goes next. Each March, the team is given an opportunity to weigh in on my leadership, the organization, their work, the professional development they need, and how their work aligns with their personal and career trajectories.

This process teaches us what part of their job feeds their soul. Research shows that motivation is less dependent on compensation or performance metrics and more dependent on whether the work actually interests the employee. Both the structure of the work, like autonomy, and the substance of the work are important when it comes to interest.

For each person on the team, we then assess grunt work (which is distributed across all team members), mission-driven deliverables, and gold, which is the work that feeds our souls.

Once we have built out the budget and the scope of work for the next year, we get buy-in from the leadership team and then our board.

We circle back to each team member before the end of the fiscal year in June and present to them their scope of work for the following year along with compensation.

This process allows for annual buy-in to how the organization will move the mission. It also creates a predictable time of the year for turnover and hiring as needed.

If you are familiar with the Knight-Lenfest Newsroom Initiative Tablestakes, then you will understand that heading into each new school year, this process allows us to know who is on the EdNC bus.

Does the leader and the organization have a theory of change?

To me, there is an important difference between a strategic plan and a theory of change. I am not a fan of strategic plans, which I find to be dependent on things out of our control, like politics, which can effect windows of opportunity; the economy, which can effect available resources; or the unexpected, like a pandemic, which can disrupt literally everything.

But a theory of change spells out what the organization is going to do to move its mission no matter what. And it becomes even more important during a crisis.

At EdNC, we have eight drivers of impact in our theory of change: journalism as the fourth estate in a democracy, in-depth research, building and engaging our audience, tracking the impact of our work, moving the needle on policy change, responsive experimentation in the new media and nonprofit world, the broad base of financial support for our work, and increasing leadership capacity statewide.

Two drivers played outsized roles in our ability to thrive in the pandemic.

Impact

No article has shaped my thinking about impact more than this article in the Harvard Business Review on measuring the impact of ideas. When thinking about impact there are four dangers: thinking no one else can do the work, looking for the easiest way to assess impact, only assessing impact internally, and not assessing impact against market demand.

Sui generis is a Latin phrase that means “of its own kind.” It is human nature to want to think we are special and unique, that only we can do this work. And as we move into our professional careers it is tempting to think there is something special and unique about our leadership or our organization. Leaders who allow this to perpetuate are more likely not to have any process to assess impact.

Another danger is the streetlight effect, a kind of observational bias that leads people to search for things where it is easiest to look. The idea comes from when people lose their keys at night, they then most often look for them where they can see them. Leaders who are not aware of this effect often assess the easiest things instead of the best things when it comes to impact.

The third danger is that many often only assess impact internally – what does the CEO, what does the team, what does the board, what do funders think – and if those groups think the impact is good, well then swell. That creates a real blind spot. It is important for leaders to assess how external stakeholders, especially those served, assess and define our impact.

Finally, it is also important for leaders and organizations to assess where their work intersects with demand, and where their work is better than what is available elsewhere in the market. We should be striving for excellence, y’all.

Leadership development

People think of EdNC as a news outlet, but you don’t hear me giving speeches about education journalism. We invest in leaders — our team, our board, our strategic council, other leaders and organizations, internally and externally, providing personal and professional development not just for now but for what’s next. We believe in the Aspen Institute’s call to connect leadership of the self with leadership of the organization with leadership of society.

When all that you do is seen through the lens of leadership development, it breaks down turf, and it is easier to see that the challenges and opportunities ahead are too big for one leader, one organization.

Once the orientation is beyond the leader and the organization, once it is beyond the now, leaders and organizations naturally move into a collaborative, force-amplifier postures.

For example, at the beginning of the pandemic, we unbranded our moments of hope so that all education organizations would push them out into the world.

Turns out journalism is the easy-ish part. The hard part is this…

Is the leader and the organization comfortable with interrogation?

When we were building EdNC, we questioned everything and assumed nothing. Where do people get their news? What do they do with it? Did we need offices? Did we need benefits? Why a 40-hour work week? Life balance or life integration? Do team members need journalism degrees? How can we organize internal communications for efficiency so we can spend most of our time doing the work? What management structures are really needed? What editing model will work best for our people and not edit out voice? What do we know about building high-functioning teams?

Interrogation helps leaders discern what is really most important.

We ended up with a team of peer experts that works at least 50 hours most weeks, but we take additional time off around July 4th and Christmas, we pay above market (everyone on our team makes more than the median for journalists statewide and nationally), they buy their benefits in the marketplace, and their offices are the classrooms and communities where they are reporting.

The interrogation process also helps leaders and organization build mission-oriented hiring practices, which in the pandemic led to less turnover for us.

One school leader told me she built her whole hiring process with an eye towards discerning whether the applicant really believes each student can actually do the work. She said she could teach teachers how to teach and she could teach school leaders how to lead, but the intrinsic belief in each student’s aptitude was the best predicator in her schools of teacher effectiveness.

Another superintendent used interrogation to discern that in his district, the hiring process didn’t need to lead to the most qualified principal. Instead, it needed to lead to the right principal for the students, teachers, parents, and community at that particular moment in time.

At EdNC, we use the IOPT tool to intentionally build our team across the four quadrants of leadership and followership: change and conservation, performance and perfection. The use of a team building tool leads to fewer conflicts aka less drama, increased empathy, optimizing productivity, recruiting for fit, and a happier culture. Rupen says working at EdNC is like Thanksgiving every day.

Does the leader have a process for integrating diversity + equity + inclusion = belonging into the work? Is the leader supported to do this work?

Leaders who thrive have systems to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion into the leadership, work, and culture of the organization.

Our DEI work happens across four dimensions – intrapersonal (for example, each team member completed 32 hours of DEI training in 2021), organizational (for example, we changed our governance model to be aligned with our DEI work incorporating principles of distributed leadership), community (for example, we were the first in North Carolina to have an equity editor and equity auditor), and systems (for example, we were in the inaugural cohort of the NC Media Equity Project).

Is the leadership, the work, and the organization crisis-ready?

Superintendent Garrett also says, “Crisis doesn’t build character, it reveals character.”

We know a lot about human behavior in crisis. Former education journalist Amanda Ripley wrote a book about it before the pandemic based on research of how humans behave when there is a natural disaster, an airplane crash, a fire, or other unanticipated crisis. She discerned three phases: disbelief, deliberation, and decisive action.

In the first phase, disbelief, the question is how fast does the leader and the organization push through disbelief?

In the second phase, deliberation, there is both internal and collective deliberation. Collective deliberation is more effective in crisis, Ripley says, when leaders trust the team with complex information and when there is intrinsic wisdom and trust.

In the third phase, the leader and the organization move into action. In the first weeks of the pandemic, we oriented our work around the concept of help, answering audience questions, and then we layered on the concept of hope, providing content that would provide encouragement in unprecedented times.

Within days, we realized superintendents were in central offices (some of our central office teams never went home). We realized principals were in their schools and in many places teachers were teaching remote classes from their classrooms to have access to internet. Some of our schools were big enough that they were able to socially distance all of their students from the beginning. Between the start of the pandemic and the availability of a vaccine, we safely visited 45 school districts and 29 community colleges in person.

The pandemic called the question of who we were as leaders and as an organization. We say we want to be the best in the world in listening. We say our offices are the classrooms and schools, the communities and the lives of those we serve. Not showing up wasn’t an option for us.

Which leads me to the story of Caroline.

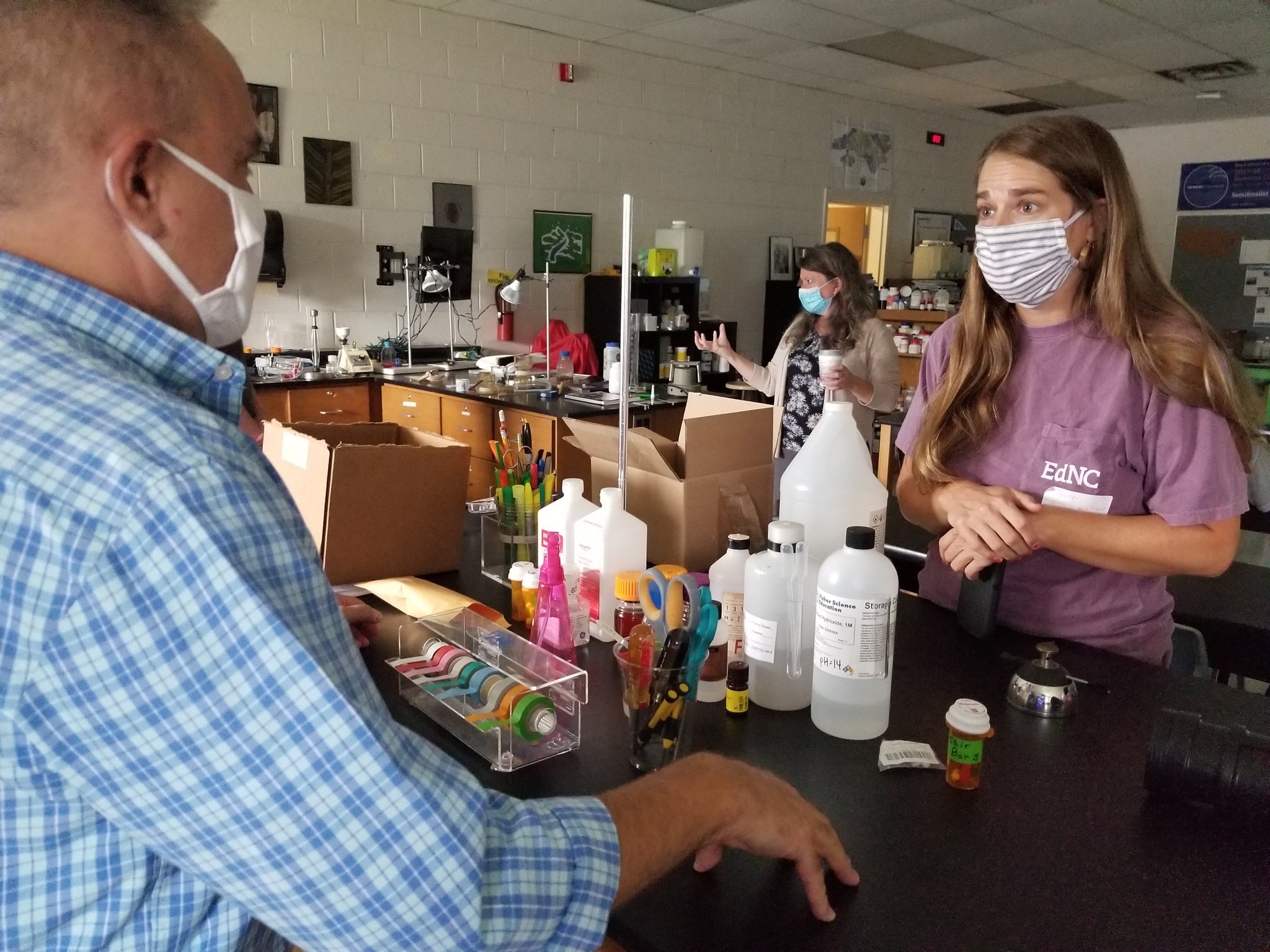

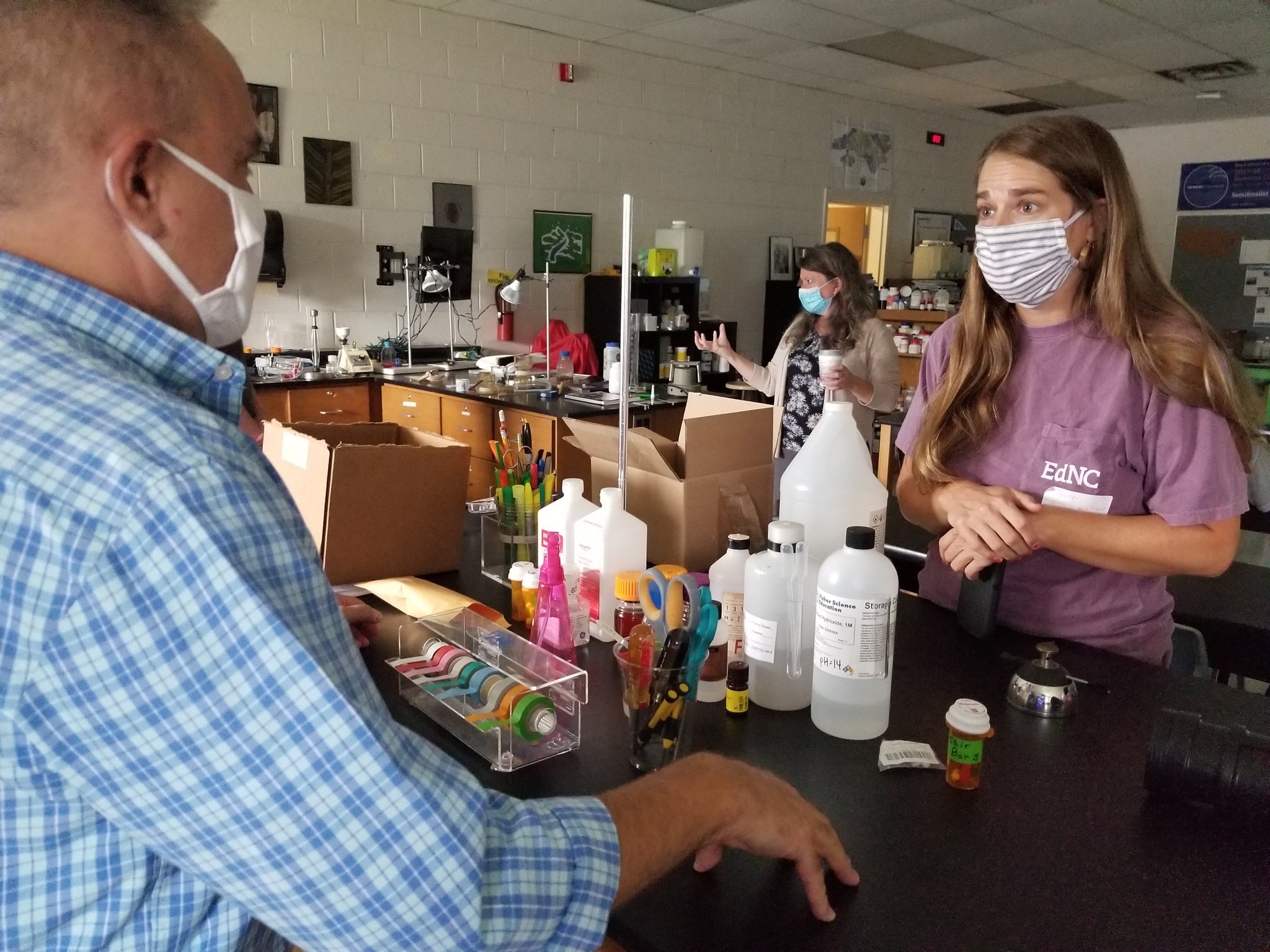

Caroline is our director of rural storytelling and strategy. She is on the road. A lot.

She was the person on our team most scared of COVID. The idea of getting someone else sick was untenable to her.

For Caroline, there was no phase of disbelief, and as soon as Gov. Roy Cooper issued the executive order declaring a state of emergency, she moved out of her house with her roommate and into a tiny house with her pup, Judge.

Caroline also moved quicker than anyone on our team through an internal deliberation process that allowed her to get back out on the road.

Long before the pandemic, Caroline’s relationships with those we serve was built on trust. She knew schools would do everything they could to make classrooms safe, and she also believed she could teach herself how to be safe as she traveled so as not to spread the virus.

She started by camping on her car. Judge went with her. She was the first on our team to hold a socially-distanced, in-person meeting inside. I can’t describe for you the sense of relief we all shared when vaccines became available.

At a time when confidence in leaders dropped and fewer and fewer wanted to step into leadership roles, the mutual trust and shared sense of responsibility we feel with our schools and community colleges across North Carolina inspired Caroline and our team to continue to tell stories in person that otherwise would not have been told.

This report found that for schools and districts who took on COVID effectively, four things were true: a shared vision, a process to prioritize challenges, a mindset of saying yes to innovation, and an iterative process in place until something just became accepted as the way to do things. This led to “organizational humaneness” and “pervasive coherence.”

These findings were true for us at EdNC. In addition, we said out loud and often, “communicate, communicate, and communicate.” We attended to the wellbeing of our team, providing equity coaches, wellness stipends (which could be used for anything without judgment except alcohol), additional paid leave, and inflation adjustments.

These practices bind us to each other, those we serve, and our mission.

Does the leader and organization have the ability to harness the power of building from the ground up?

In China, while they are modernizing existing cities, they are also building cities of the future from the ground up with new designs for infrastructure, including water and electricity.

Seeing one of these new cities made me wonder how we could harness and then leverage the power of building from the ground up for our students. Does it necessarily require building new schools, new systems, I wondered.

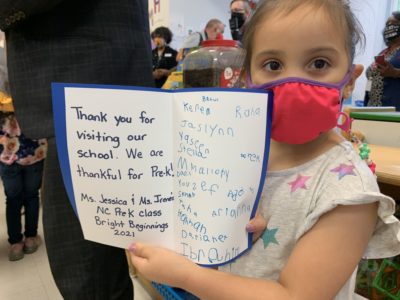

A superintendent at the Schlechty convening said no. He suggested we focus on beginning anew the efficacy of the student experience of learning from pre-K on up.

Posing those questions and prompting those solutions is what we do.

I’ll leave the question of whether every state needs an EdNC to you, but the common denominator in all that we publish is that it is information designed to prompt the conversations and relationships we believe will then prompt change. It is infused with possibility and hope and love at a time when most information is polarized and politicized.

And, for sure, I believe every student in every state deserves that.

Thank you

A personal and professional thank you to all of our superintendents in North Carolina. I watched you iterate every single system that comprises our learning environments, including nutrition and transportation, while managing a massive infusion of federal dollars, over and over throughout the pandemic.

You teach me day in and day out how to manage change and lead from the heart with students at the center of our collective work. As you reflect on all we have been through, I’d love to know the lenses important to you.

Thank you.