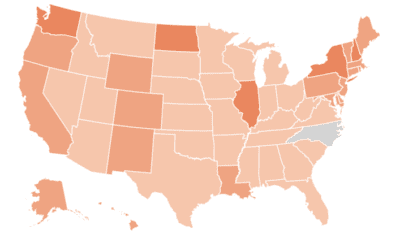

Republican state legislators often appear in a rush to embed into law and budget as much of their fiscal, social, and educational agendas as they can in case their veto-proof majority evaporates with the shifting of political winds. A prime example is North Carolina’s relatively new program of offering state-funded vouchers for children of lower-income parents to attend private schools.

The General Assembly enacted its voucher system in 2013, with the first round of assistance distributed for the 2014-15 school year. The policy initiative came from the House, especially through the persistent advocacy of Rep. Skip Stam.

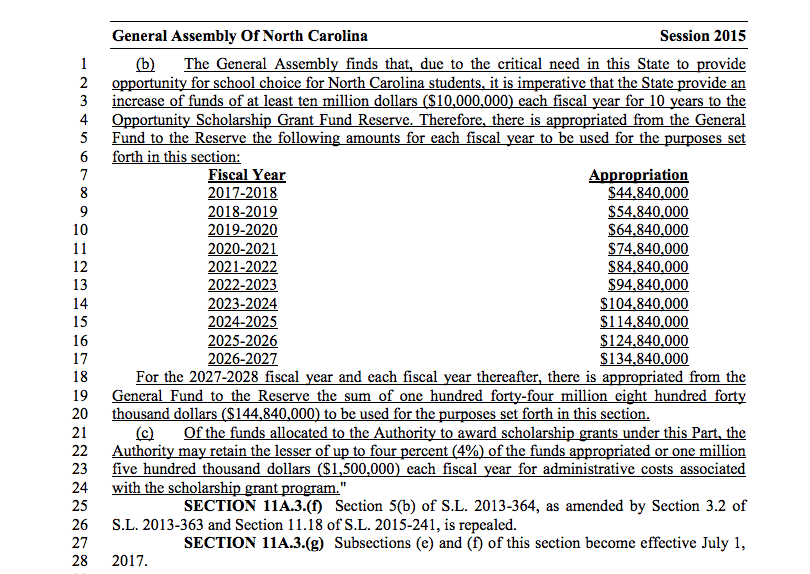

Now, in a shift from one side of the Legislative Building to the other, the Senate has stepped up with a sweeping proposal to expand vouchers over the next decade. The Senate budget contains legislation, sponsored by Sen. Chad Barefoot, that would create a reserve fund, designed to increase by $10 million a year, to finance vouchers into 2027.

In response, some House Republicans have voiced concerns about going too far, too fast. The issue is among many under negotiation in the House-Senate conference committee on the General Fund budget.

For lawmakers interested in data-based decision-making, new research raises a caution flag. The rationale for the North Carolina “Opportunity Scholarships,’’ as the vouchers are branded, is to give parents the option of switching their children from a public school they find inadequate to a private school. Studies in Indiana and Louisiana have found that vouchers for private schools have not actually produced improved educational outcomes, as measured by test scores, for its intended beneficiaries. You can find insightful analyses on school choice and vouchers from different perspectives in essays by Mark Dynarski of the Brookings Institution and Martin R. West, an associate professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Looking specifically at the Louisiana and Indiana studies, Dynarski reports that the research finds “that public school students that received vouchers to attend private schools subsequently scored lower on reading and math tests compared to similar students that remained in public schools. The magnitudes of the negative impacts were large.”

As Dynarski points out, federal, state and local policies have put public schools under pressure to show improved attainment through testing. At the same time, private schools have not faced similar accountability mandates. Thus, he writes, “More needs to be known about long-term outcomes from these recently implemented voucher programs to make the case that they are a good investment of public funds.”

In his essay in EducationNext, West takes a somewhat more sympathetic attitude toward “continued experimentation’’ with school choice in various forms. He points to studies that show a slight increase in college-going among voucher-funded students in private schools. Still, West reports:

“This research does not show that private or charter schools are always more effective than district schools in raising student performance on standardized tests – the indicator that is often put forth as a measure of a school’s success. In fact, there is little evidence that using a voucher to enroll in a private school improves student test scores…”

In their rush to legislate, lawmakers spend too little time examining findings from credible research — and specifically with regard to vouchers, have paid little heed to sound public policy implementation. In North Carolina, legislators have authorized vouchers without the kinds of requirements that would let them know whether the program is actually working.

The legislature has not imposed curriculum standards on private schools with voucher-funded students, or requirements for student achievement. The legislature mandates that these private schools give a standardized test — but it didn’t specify which test. The legislature does not require that schools with voucher-assisted students hire teachers with the qualifications required in public schools. In many ways, the voucher system provides state funding to students in private schools without holding them accountable as legislators would hold public schools accountable.

Of course, we all know that preK-12 education in North Carolina — as in the United States — has long come from a mix of public and private institutions, of varying quality. And it’s going to remain a mix, with public and private schools as uneven in their educational prowess as public schools, some potent, some weak.

Even as they have to cope with a more competitive marketplace, public schools will remain the principal educator of the vast majority of young Americans. Whatever the future of vouchers and school-choice options, strong public schools will remain essential to civic cohesiveness and economic vitality.

So then, in terms of assuring North Carolina’s young people with a sound, basic education, as the state constitution requires, what does the state gain by having public funds support students in private schools that do not perform as well as public schools? The research from other states at least ought to have lawmakers asking themselves that question and arming themselves with knowledge before legislating.

Recommended reading