|

|

In that angst-ridden spring of 2020, when schools shut down across the land, it seemed that the COVID-19 crisis could serve as a pivot to a rejuvenating “new normal” in public education. “Never let a good crisis go to waste,” as Machiavelli and Winston Churchill said in their own times.

As it played out, however, the pandemic did not exert a pull on Americans to come together. Polarization persisted. And in North Carolina and in other states with Republican-majority legislatures, a pre-pandemic education agenda has gained ascendancy.

The bluntly dramatic findings of the Covid Crisis Group, released this week, offer information and insight into how federal failures “fed toxic politics” and further divided the country. The group’s director, Philip Zelikow, a historian at the University of Virginia who previously served as the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, described the pandemic as “the most catalytic trauma the United States has experienced since the second world war.”

The group of 34 specialists issued its findings in a book, “Lessons from the Covid War: An Investigative Report,” and in a live-streamed conference hosted by the National Academy of Medicine. The academy president, Victor Dzau, former CEO of the Duke University Health System, served on the study panel.

Early in the pandemic, said Zelikow, red states and blue states adopted similar approaches to containing the coronavirus, with authorities thinking that restrictions would last only a few weeks. But, he said, “containment failed and federal crisis management collapsed under President Trump’s leadership.”

“By late April, as a frightened and bewildered country became more and more confused about continuing business and school closures, and after some brow-raising comments at a White House briefing in which he discussed treating the virus with light, heat, or disinfectant, Trump essentially detached himself from his own government,” the group’s report says.

Zelikow said that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “misjudged” how the virus transmitted from person to person and that poor communication “undermined” efforts to thwart misinformation. Without saying so explicitly, he indicated that schools could have reopened safely sooner than most did so, had federal guidance not faltered.

“Practical tools to reopen schools and reopen businesses could have been deployed much sooner,” said Zelikow. “But most communities did not have the tools.”

In North Carolina, Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper and Mandy Cohen, secretary of health and human services, held regular televised briefings during the crisis with the message that they were making data-driven decisions. And yet, as Cohen later reflected, “Unfortunately, we went into this crisis with a lack of cohesion and trust. I think what a lot of folks are starting to understand about crisis response is that trust is really, really hard to build during a crisis … We definitely saw that countries which had more cohesive and trusting societies had much better responses.”

As time went on, protestors showed up at the Governor’s Mansion to demand the reopening of schools faster than the Cooper-Cohen timetable. Republican lawmakers called prolonged school closings a policy failure and moved to curtail a governor’s power to impose public emergencies.

Pushback arose against the public health measures of wearing masks and getting vaccinated. Local school board meetings became venues for heated parental objections to books and classroom teaching on race and gender. The General Assembly has under consideration measures to give lawmakers more power through appointments to oversee challenges to instructional materials and to review the standard course of study — as well as to expand public support of private schools through financial aid to families.

Still, the COVID crisis holds out lessons about how to minimize destruction and maximize recovery in education. It showed the importance of extending wireless internet access to all corners of the state, of the professionalism of educators, and of schools in making sure young people are adequately fed.

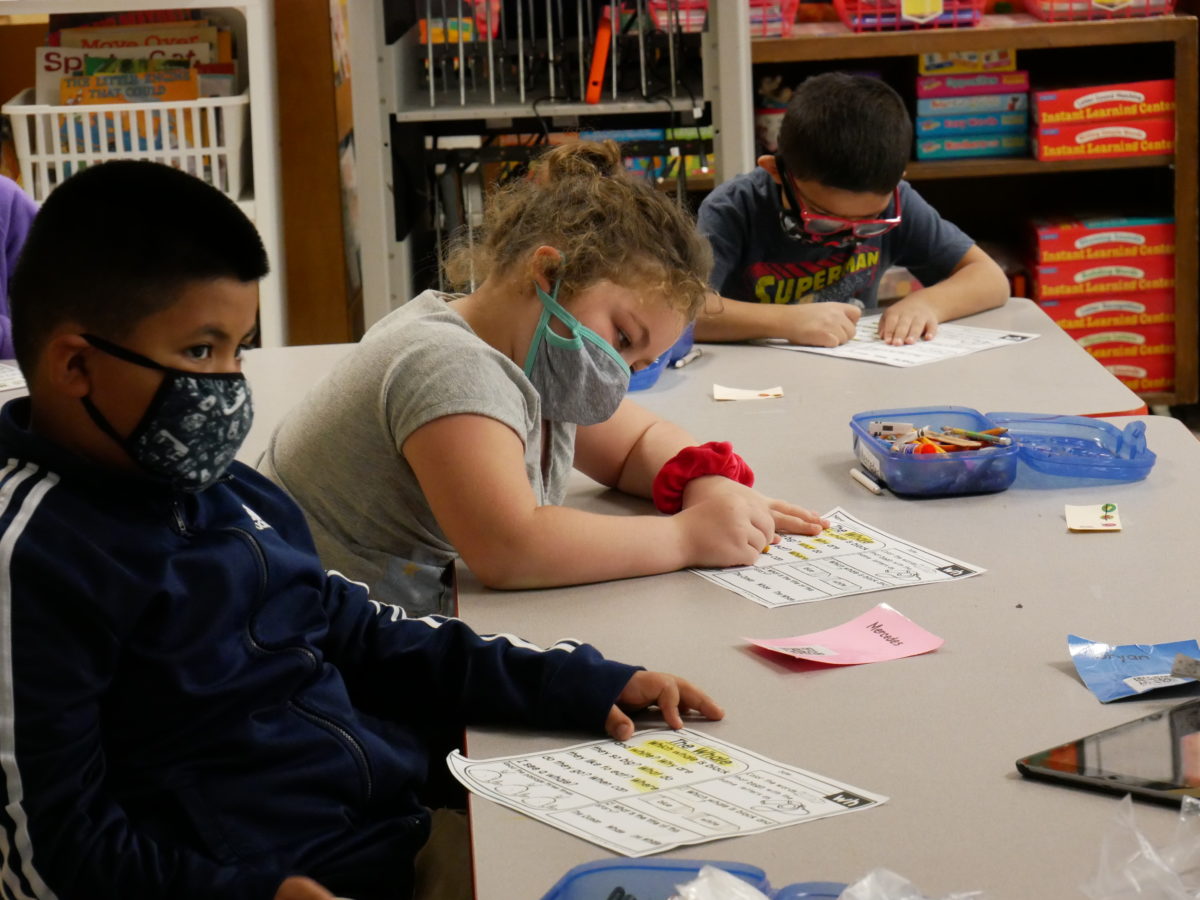

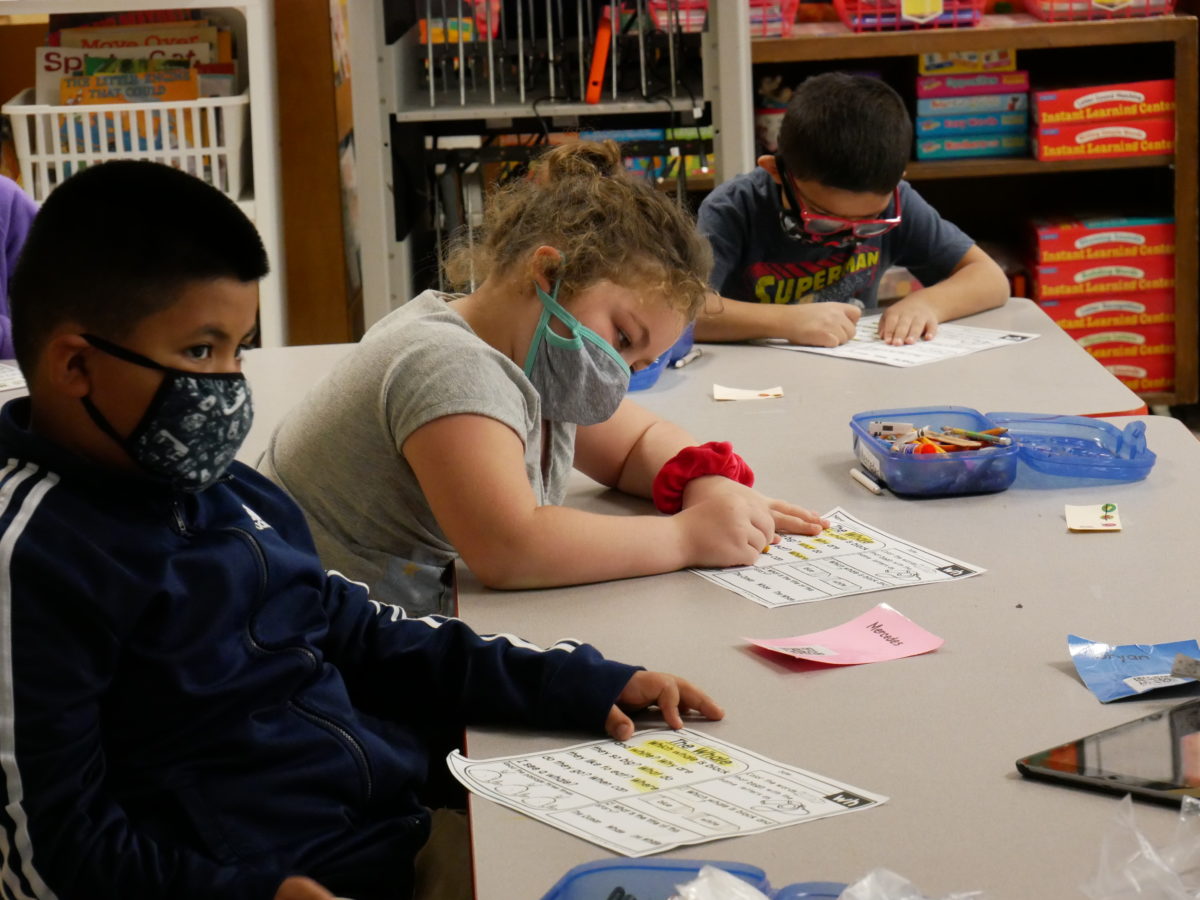

As neighborhoods and communities developed “pods” for students to study together during virtual classes, the crisis helped illuminate the potency of tutoring. Educators now have an enhanced understanding of social and emotional support for students as a foundation for academic achievement.

In his presentation on the Covid Crisis Group’s findings, Zelikow posed a question as a challenge to this powerful democratic republic: “Is the United States still capable of solving big problems?” To which, let’s add, is North Carolina?