“In so far as those who purvey the news make of their own beliefs a higher law than truth, they are attacking the foundations of our constitutional system. There can be no higher law in journalism than to tell the truth and shame the devil.”

Walter Lippmann, a major public intellectual of the 20th Century, wrote those words in “Liberty and the News,” a slender book of three essays published precisely 100 years ago. Though writing in an earlier age, Lippmann’s thinking on how to advance effective governance in a complex democratic society remains provocative and instructive — to journalists and citizens, to teachers and their students.

Lippmann was in his early 30s when he wrote “Liberty and the News,” published in 1920, and his more expansive “Public Opinion,” published two years later. He became known as the father of objective journalism, a concept much debated and misconstrued, that has emerged again as a hot topic in today’s contentious politics.

Martin Baron, executive editor of The Washington Post, cited Lippmann last week in a lecture to students of the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media. He observed both that the Trump presidency has “sought to subvert the very idea of objective fact” and that the “public’s understanding about the role of the press in American democracy is eroding.”

“In this moment,” said Baron, “it’s important to remember that the rights we inherited, including the right to free expression, depend heavily on the willingness of the public to defend them.”

And, it should be added, for schools to teach them. In his time, Lippmann worried over what he saw as a lack of education in the historic, cultural, and religious underpinning of democratic society.

Lippmann, an elitist who wrote dense, nuanced prose, reacted against the propaganda of World War I and the “yellow” journalism of his time. He was not a day-to-day reporter; he advocated and practiced what he called “explained news.” To Lippmann — and to Baron — objective journalism is not he-said-she-said false balance in every article of news but rather a process of pursuing truth with facts put into context and perspective.

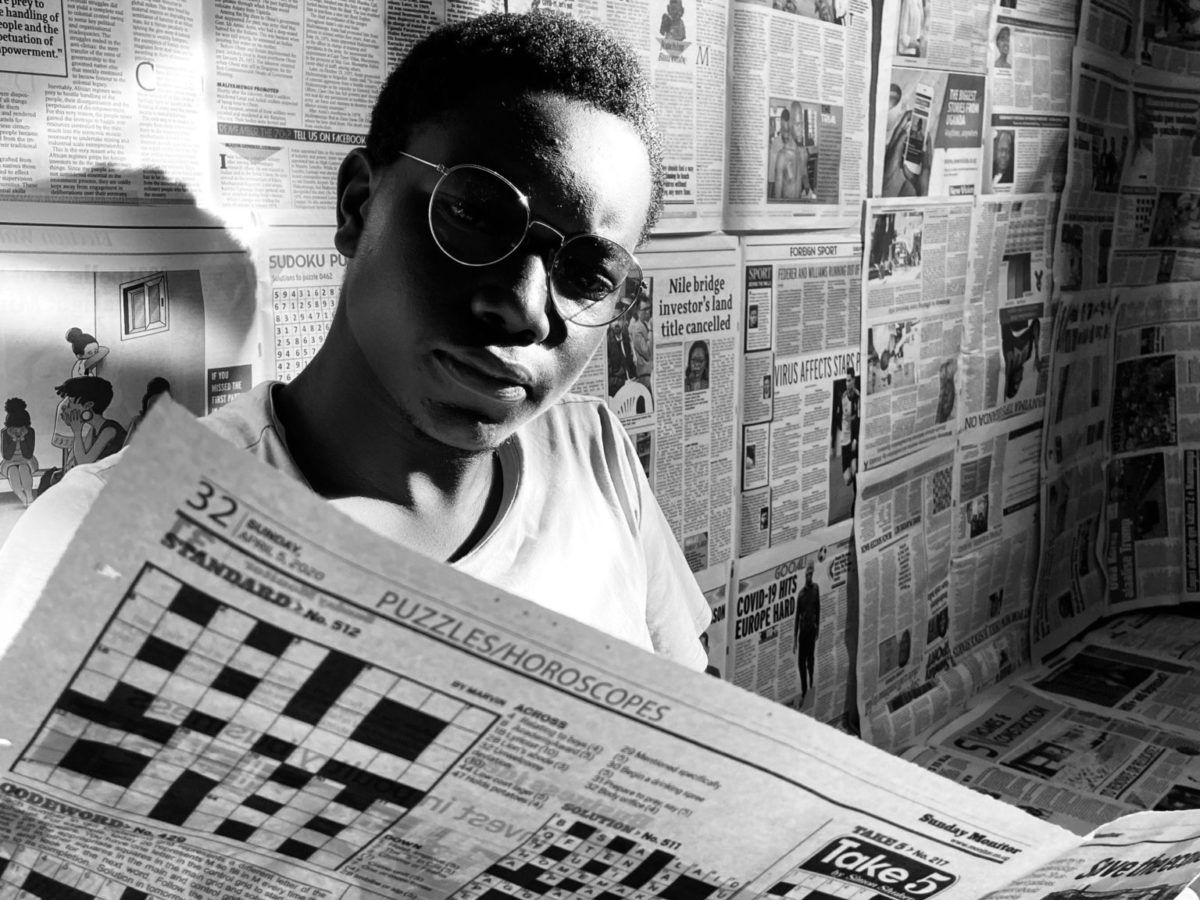

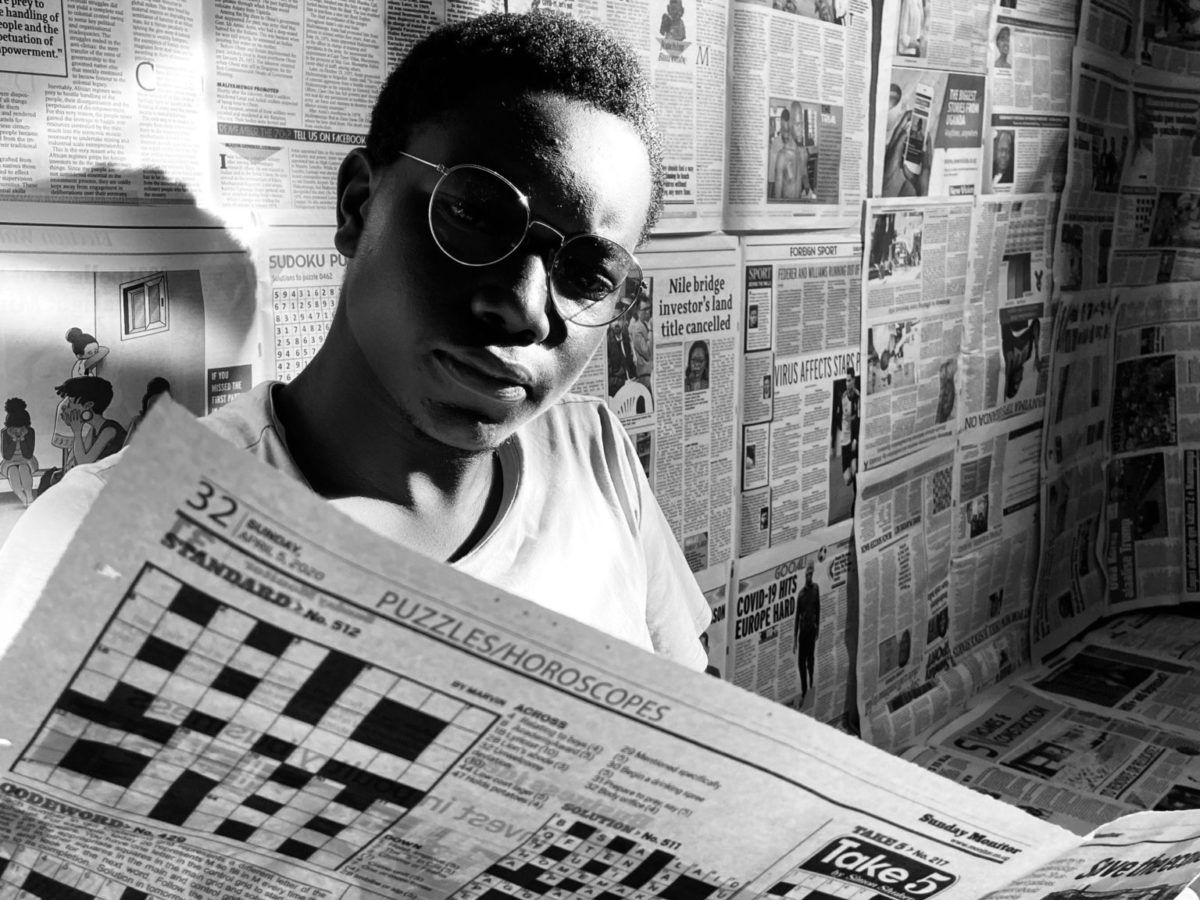

To Lippmann, the press meant largely newspapers as well as commentary magazines like the New Republic of which he was a co-founder. Lippmann died in 1974, well before the digital media maelstrom that allows misinformation and disinformation to travel easily along with diverse professional journalism, academic research, and official documents. In schools, “news literacy” should become a key component of civic education. (The Poynter Institute offers resources.)

In the era of Trump, polarized politics, COVID-19, and Black Lives Matter, national media have found means to sustain audiences and even thrive. The New York Times now reports it has 6.5 million subscriptions, including 5.7 million digital-only. The Washington Post has reached 1 million digital subscriptions. In his UNC lecture, Baron said the Post newsroom will have grown from 580 people seven years ago to 900 by the end of 2020.

In states, cities and towns, an alternative reality has played out. “From 2008 to 2019,” reports Pew Research, “overall newsroom employment in the U.S. dropped by 23%,” representing a loss of about 27,000 jobs. Digital news employment rose from 7,400 to 16,000.

My UNC journalism school colleague Penny Abernathy has influenced the national conversation over the future of journalism with her research on “news deserts” — places without a news outlet — and “ghost newspapers” — publications with too few journalists to offer much of substance to their communities.

With the pandemic and recession accelerating local losses, she writes in her recent report, “This is a watershed year, and the choices we make in 2020 — as citizens, policymakers, and industry leaders — will determine the future of the local news landscape. Will our actions — or inactions — lead to an ‘extinction-level event’ of local newspapers?”

Meanwhile, the United States has as many as 500 online news sites — some national, some statewide, some local, some general interest, some political, some subject-focused, some consumer-oriented. As one example, EdNC entered this realm more than five years ago as a hybrid news and policy nonprofit devoted to informing the great education debates in North Carolina.

The shape of the future of media remains a societal work in progress. Lippmann defined the stakes in concluding a chapter with words that still ring a century later: “Liberty is the name we give to measures by which we protect and increase the veracity of the information upon which we act.”