For the first time in at least 10 school years, a majority of the state’s first, second, and third-grade students did not demonstrate reading proficiency, according to a report of 2020-21 testing from the Department of Public Instruction’s Office of Early Learning. The data were presented Wednesday to the State Board of Education.

State leaders have long flagged low reading proficiency scores for North Carolina students, but the most recent data are especially troubling.

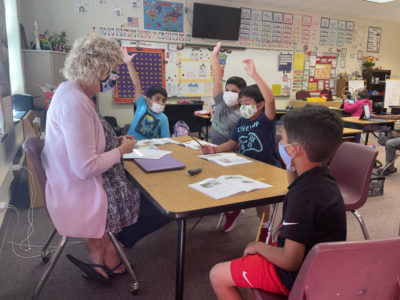

Presenters and Board members said the results reflect the pandemic’s impact on student learning while also demonstrating the ways in which the pandemic exacerbates pre-existing issues and the compounded effect of those factors on historically marginalized students.

“It goes without saying, our earliest learners took a hard hit during the pandemic,” Office of Early Learning Director Amy Rhyne told the Board. “Now more than ever, we have to make sure there’s a solid plan in place to support the gaps that have been created during this time.”

Rhyne also provided results from a survey of North Carolina K-3 teachers conducted by the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR), which showed that at least 60% of teachers are knowledgeable in high-quality reading instruction but less than 40% felt comfortable applying that knowledge in the classroom.

Inside the recent testing results

The data for first-graders and second-graders are from end-of-grade standardized tests last year (2020-21). The state waived end-of-grade testing in 2019-20, but the results from last year show a stark drop from the 2018-19 results.

At the end of last school year, only 38.5% of first-graders demonstrated proficiency, dropping 32.6 percentage points from 71.1% two school years earlier. Last year, 41.3% of second-graders demonstrated proficiency, down 36.8 points from 78.1% two school years earlier.

The third-grade scores are from a collection of last year’s EOG and this year’s beginning-of-grade standardized testing. The results show that only 43.7% of students demonstrated proficiency the day they took the tests. That’s down from 57.3% two years earlier.

“This was in the works before the pandemic,” state Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt said during discussion with the Board after the presentation. Truitt said that’s why the state has focused on grounding reading instruction in the science of reading and is in the process of a four-year implementation plan. It asks a lot of teachers, she acknowledged, but she said there is no other choice.

“We can’t continue to have 24,000 students graduating from third grade not able to read,” she said. “Third-grade reading is the No. 1 academic predictor of postsecondary success. … We must change this trajectory, and we have to use science and data to do it.”

What about underserved students?

The data disaggregated by race, income, and learning differences were not available at the time of publication. Truitt said she had not seen the most recent disaggregated data, but said she memorized some of the data from the 2018-19 school year and is concerned — particularly for the consequences in later grades.

“What it tells us is that 67% of eighth-graders in North Carolina start high school not proficient,” Truitt said. “Forty-eight percent of Hispanic students start ninth grade [not proficient], and 14% of African Americans. So, we can only guess what that disaggregated data looks like [now].”

When the state enacted Read to Achieve in 2012, summer reading camps were a centerpiece of the legislation aimed at supporting students who were falling behind.

The recent data, however, showed low rates of attendance for students eligible for priority enrollment in summer reading camps. Only about 30% of first- and second-graders who were eligible attended a reading camp. Only 46% of eligible third-grade students attended.

The data also underscore the urgency of current efforts to improve summer reading camps. Of the 17,317 third-graders who attended reading camps statewide, only 15% tested as proficient afterward. Only about 9% of the 16,789 second-graders and 18,862 first-graders tested as proficient afterward.

A way forward through EPSA?

The state enacted the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021 in April to address the persistently bleak early reading landscape.

Included in the law, which aims to improve teacher preparation and instruction by grounding teachers in the science of reading, is a mandate that every teacher from pre-K through fifth grade receive training in Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS). DPI has arranged for this training to occur across three cohorts of districts between now and 2024. The first cohort began in August, and the second will start in January.

The law also requires that DPI create a set of standards for literacy instruction. During an update to the Board on Wednesday, Academic Standards Assistant Director Kristi Day clarified that these standards are different from standard courses of study, which the Board approves for academic subjects.

While the standard course of study sets a level of expectations for students, the literacy instruction standards that DPI is working on set a level of expectations for teachers, Day said.

“We’re also working on transitioning planning and sustainability planning based on what districts already have in place and what they need,” Rhyne said.

Rhyne said the FCRR report suggests that teachers are starting with a good base of knowledge as they begin LETRS training. A similar study administered by FCRR after Mississippi completed statewide LETRS training showed an increase of about 14 percentile points in teacher knowledge after the training.

However, the recommendations in both Mississippi and North Carolina included a call for in-school coaching for reading teachers to help teachers apply their knowledge in the classroom.

The EPSA does not provide for in-school coaches. While DPI has regional coaches and plans to support existing district and school instructional coaches, Rhyne said she does not know whether the General Assembly will provide funding for in-school reading coaches in the state budget.