|

|

Laura Bilbro-Berry stepped into her first classroom as a teacher in 1992. She realized both the weight and the depth of her responsibility almost immediately. About a third of her elementary school students struggled with reading, and the “whole language” instructional approach that her college taught her to use wasn’t working.

“I realized pretty early on that I needed more information,” she said. “And so I found those things that I knew were really important. I didn’t have a name for that information. We didn’t call it the ‘science of reading.’ But I knew that’s what my kids needed in my classroom.”

Nearly 30 years later, Bilbro-Berry leads the UNC System’s educator preparation program (EPP), which produces about 40% of the state’s teachers. Now, Bilbro-Berry is in position to make sure those future teachers get the information that she didn’t in college.

By fall 2022, every UNC System EPP will align its instruction with a Literacy Framework the system finalized in March. It’s a massive undertaking, but one that Bilbro-Berry says is overdue.

“Sometimes in education we will do things and then we don’t give enough time to ensure that they’re working,” Bilbro-Berry said. “But I think, with this, the most encouraging thing is that we’re really investing in people. Good teachers matter. We know that they do; the research tells us they do. And so our responsibility as UNC System ed prep programs is to make sure that we’re putting out good teachers.”

A framework for producing good reading teachers

The Literacy Framework is the centerpiece of the UNC System’s efforts to ground coursework in the science of reading. Right now, EPPs throughout the system are using that document to conduct a self-audit of their curriculum.

But the genesis of that document begins with another one — a report called Leading on Literacy, which Margaret Spellings commissioned while she was UNC System president in 2017.

It recommended forming an EPP advisory group to align instruction with current research, particularly with respect to literacy. That group was formed and, through communities of practice, began researching solutions and mapping out recommendations.

That work led to the UNC Board of Governors’ passage of a resolution on April 17, 2020, that tasked the system with developing “a common framework for literacy instruction in teacher preparation” that is “based on the abundance of evidence on effective reading instruction, complies with state law and regulation, and ensures that teaching candidates receive explicit, systematic, and scaffolded instruction in the essential components of reading.”

Last fall, the UNC System used an external committee to select eight faculty members from its institutions. These eight, called literacy fellows, spent several months in debate and compromise to create a set of competencies and sub-competencies that every institution should teach to future elementary school teachers.

“People share a common goal,” UNC System President Peter Hans said. “They can learn from one another and listen to one another, and I think build consensus. That does cause me to be quietly optimistic about our long-term chances here.”

UNC System schools are doing some self-reflection

The literacy fellows completed a draft before Christmas, and the system sent it to each EPP. The fellows returned from holiday to “pages and pages and pages and pages” of feedback, Bilbro-Berry said.

The final product, completed in March, includes eight essential components, as well as numerous sub-competencies, for reading instruction. The literacy fellows created a template for EPPs to self-audit their current alignment with the literacy framework. That process is occurring now, in three phases.

“They have to determine whether a particular sub-competency is being introduced, whether or not teacher candidates have practiced that particular sub-competency, and then also the assessment of that sub-competency,” Bilbro-Berry said.

In the first phase, completed in May, EPPs assessed alignment with three essential components: phonemic awareness, phonics and decoding, and fluency. For the second phase, which ends in October, EPPs will examine vocabulary and reading comprehension. In the final phase, which ends in December, they will assess concept-to-print, oral language, and writing.

“Nobody likes to do a self-study, but I think because it was developed by faculty who know how curriculum works and understand how curriculum changes can work, we really feel like our EPPs have owned this self-study,” Bilbro-Berry said. “They’ve looked at their programs and realized they had some holes and are addressing that.”

How the system will measure accountability

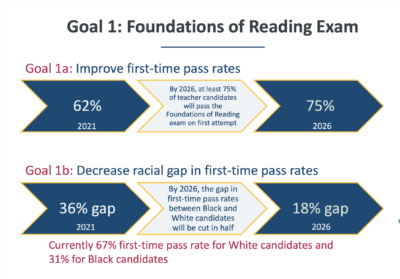

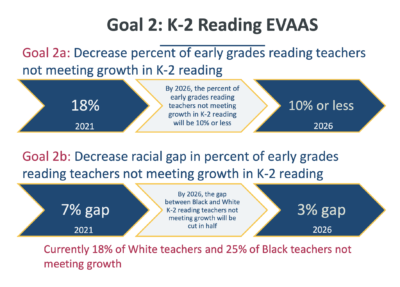

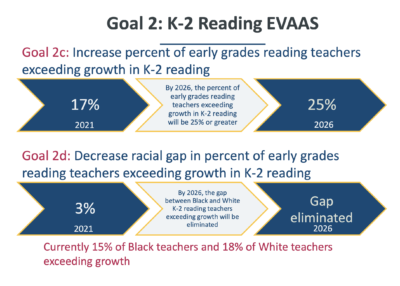

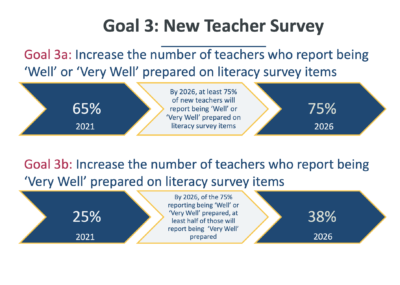

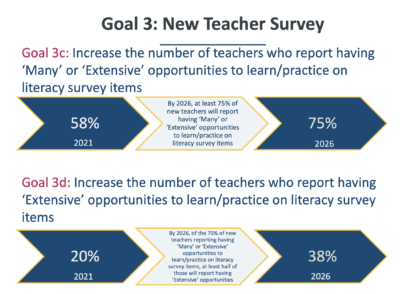

At this month’s meeting of the UNC Board of Governors, Bilbro-Berry presented three benchmarks for measuring progress with implementing the literacy framework: pass rates on the Foundations of Reading licensure exam, EVAAS scores, and new teacher survey responses.

Getting this done right is high stakes, Hans says, especially given the system’s role in supplying public school elementary teachers.

“I absolutely feel an extra responsibility because our schools of education do provide the largest number of teachers in North Carolina’s classrooms,” he said. “We’ve got to put our shoulder to the wheel on this issue. We owe it to the teachers, we owe it to the students, and we owe it to the people of the state who generously fund the universities.”

Bilbro-Berry also says she owes it to herself — and, really, to deliver on a promise she made to her younger self.

It’s been 29 years since she started her journey to teach reading according to the salient research. When she found the research, she wanted others to have it, too. She told her colleagues at the school. In 2001, she became North Carolina Teacher of the Year and traveled the state telling more teachers. She knew what a difference it made for her, and she wanted to put it in the hands of every teacher she could.

Now, she directs policy for thousands of future teachers every year.

“It’s like full circle for me,” she said. “This keeps coming up throughout my life, so I feel like maybe at this point we’re going to get it done and get it right.”