This is an excerpt from “E(race)ing Inequities: The State of Racial Equity in North Carolina Public Schools” by the Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED). Go here to read the full report and to find all content related to the report, including the companion report Deep Rooted.

In this concluding section, we summarize the results of over 30 indicators of educational access and achievement examined, provide interpretations that span the full analysis and the six racial groups studied, discuss the significance of the overall findings, and explain the project’s relationship to the ongoing work of its parent organization, CREED. Numerous directions for change flow from the analysis in this report, but a full explanation of those is beyond the scope of this initial examination. Given that comprehensive analyses of racial equity in North Carolina public schools are not being conducted by other educational institutions in the state, the primary focus of the present work is to:

- Provide an empirical basis for nuanced understanding of how race influences the educational experiences of students,

- Identify key areas for future in-depth study, and

- Indicate directions for intervention intended to provide equitable access to the benefits of public education in our state.

This report asked two broad questions: 1) Does race influence educational access and outcomes? 2) Does race influence access and outcomes after accounting for other factors, such as gender, socioeconomic status, language status, (dis)ability status, and giftedness? In this section we frame our answers to those questions in terms of accumulated (dis)advantage. We seek to assess the overall educational trajectory of racial groups in the state based on aggregate levels of access and achievement/attainment. As we have done throughout the report, White students are the reference group in comparisons.

It is important to note that analyses of data already collected, like those in this report, cannot establish causal links between measurements. That is, we cannot directly link student groups with less opportunity and access to diminished educational success as measured by achievement and attainment outcomes. However, we do ask that readers recognize the clear logical relationship between access and outcomes, as well as the cyclical nature of educational (dis)advantage. Children with less access have enhanced likelihood of school failure (broadly speaking), which in turn diminishes future access/opportunity, and so forth in a fashion that tends to accumulate even more barriers to educational success.

We also call attention to the systemic nature of our findings, which assess racial equity in all schools in the state, across virtually all readily available metrics, and among all U.S. Census designated racial groups. All of this is done in the context of the statutory and policy framework set forth by the North Carolina Constitution, the General Assembly, the State Board of Education, and the Department of Public Instruction.

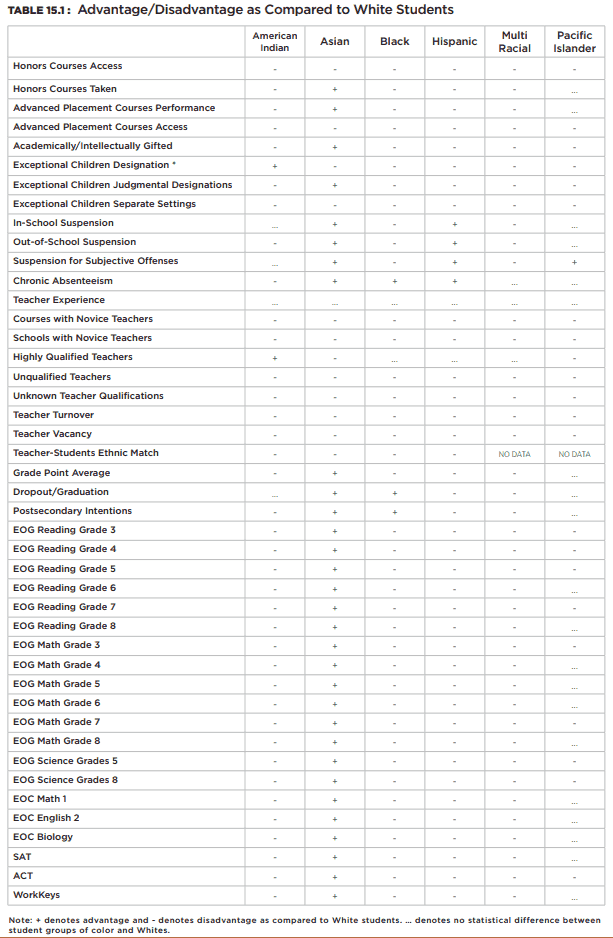

The full analysis leaves no doubt that race is a powerful predictor of access, opportunity, and outcomes in North Carolina public schools. Furthermore, race affects the educational experiences of students in a very clear and consistent fashion, with Asian and White students tending to accumulate educational advantage and non-Asian student groups of color tending to accumulate disadvantage. Table 15.1 provides a simple visual representation of the relative advantage/disadvantage of student groups of color as compared to White students. A + denotes advantage and a – denotes disadvantage as compared to White students on the same indicator. The … symbol indicates no statistical differences. With 44 points of analysis and six student groups of color, there are a total of 264 possible pairwise comparisons.

Approximately 87% (231 of 264) of comparisons were statistically significant (p≤.05), meaning there is a very low probability that the observed result was due to chance. While this kind of comparison is imprecise by nature, it provides a broad measure of the extent of educational advantage/disadvantage at the state level. Most non-significant comparisons (21 out of 33) were between Pacific Islanders and Whites, which is likely due to the small number of Pacific Islanders in the state rather than because there are not substantial differences. Given the direction of the Pacific Islander vs. White comparisons that were significant, it is likely that with more Pacific Islander students, more significant negative comparisons would be revealed.

If we compare all six student groups of color to Whites, 82% (191 out of 231) of significant comparisons indicated advantage to Whites. Most cases (31 of 41) where students of color had advantage are in comparisons between Asians and Whites (more on this below), leaving only 10 instances (out of 187) of advantage for non-Asian students of color. Thus, if we only look at the five non-Asian student groups of color, approximately 95% of significant comparisons indicated advantage to Whites.

Multiracial students were disadvantaged in every significant comparison. American Indians and Pacific Islanders were advantaged in a single comparison. Black students were disadvantaged in all but three indicators (chronic absenteeism, dropout/graduation, and postsecondary intentions). Hispanic students were disadvantaged in all but four indicators (in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, suspensions of subjective offenses, and chronic absenteeism). Asians outperformed other groups on all indicators of academic achievement and attainment despite numerous points of comparative disadvantage across the indicators of access.

Most of the symbols (+/-/…) in Table 15.1 represent predicted results of student groups of color compared to White students after controlling for other relevant factors (gender, socioeconomic status, language status, (dis)ability status, giftedness, suspension). In other words, they are not based on simple tallies or statewide averages of the various indicators. For instance, the symbols for GPA do not simply show that average GPAs among Whites are lower than Asians and higher than other groups, but that these same gaps remain after factoring out other predictors in a way that isolates the effect of race.

The remaining indicators measure exposure to benefit/penalty based on the racial composition of schools, such as Honors Courses Access, AP Courses Access, Schools with Novice Teachers, Teacher Vacancy, and Teacher Turnover. In these cases, we are asking if schools with greater proportions of students of color have different levels of access to rigorous coursework and the most effective teachers. As such, all student populations are examined together in a more binary fashion (White/not White).

While we cannot establish statistical causation, an examination of Table 15.1 and the associated results tables throughout the report make it clear that overall the same racial groups with accumulated disadvantage on access variables (i.e. teachers, rigorous coursework, discipline, EC status, AIG status) also have diminished outcomes (i.e. EOG/EOC scores, SAT, ACT, graduation). This makes it exceedingly difficult not to connect barriers to access and opportunity with attendant achievement and attainment outcomes. It also highlights the systemic nature of racial inequity in North Carolina public schools. Were all students, regardless of racial background, to enter the North Carolina public school system with similar levels of readiness, ability, and educational resources, our results suggest that the current system would function to constrain the educational success of non-Asian student groups of color in such a way that upon exiting the system, these same groups would be less prepared for college, career, and adult life. As such, the core interpretation of the full analyses conducted for this report is that in all but a handful of cases, systemic barriers to access and opportunity feed educational disadvantage among non-Asian student groups of color in North Carolina public schools.

Before we share conclusions related to the state of racial equity for individual racial groups, we should point out two bright spots in the data. Although there are clear racialized patterns in the distribution of novice teachers, racial groups in North Carolina appear to have reasonably equitable access to experienced teachers as measured by years of experience. Although statewide data includes a substantial number of teachers with ‘unknown” qualifications, North Carolina is clearly committed to staffing qualified teachers, with the vast majority having licenses and college degrees in their content area.

Asian

There are, as noted, exceptions to the overarching conclusion of our analysis that systemic barriers to access and opportunity feed educational disadvantage among non-Asian student groups of color. For instance, while they do not face the same level of systemic disadvantage, the achievement and attainment results of Asian students indicates that they, as a group, are insulated from the potentially adverse effects of over-exposure to less effective teachers and under-exposure to rigorous coursework. This may suggest that there is a “tipping point” at which the accumulated disadvantage within a racial group exceeds that group’s ability to overcome educational barriers. It may also indicate that the economic success and attendant social capital attained by Asian Americans as a social group increases their resilience to educational obstacles.

It is also likely that different student groups of color encounter the educational system in different ways. While research and theory have firmly rejected the notion that all Asian children are smarter, work harder, more docile, and more compliant (Museus & Iftikar, 2013; Teranishi, Nguyen, & Alcantar, 2016), this does not preclude the possibility that this “model minority” mythology continues to leak into the policies and practices of educational actors in our schools. Finally, while all groups of color have experienced state sanctioned discrimination, exclusion, and violence in the American education system and beyond, the degree to which present and historical racism is infused in public education is likely different across groups. An important step in disentangling the various contributors to Asians’ educational experiences would be to collect disaggregated data within the Asian demographic category to help illuminate the differences among and between the approximately 15 different ethnic Asian subgroups (Chinese, Hmong, Korean, Sri Lankan, Thai, Vietnamese, etc.)

Black

Our results for Black students represent a related exception. The pernicious history of slavery and violence against Black families throughout American history is well-documented (Anderson, 1988; Span, 2015) as is a legacy of negative stereotypes and racism against Black children in the public education system (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Staats, 2015). Our analyses reiterate these trends. Our results show that within many of the access and opportunity metrics where Black students are disadvantaged compared to other student groups, they tend to have among the highest disparities of any student group. Black students have among the highest exposure to judgmental and exclusionary exceptional children (EC) designations, the largest degree of under-selection for academically and intellectually gifted (AIG) programs, the largest disparities in in-school and out-of-school suspension, and are the most likely to be suspended for subjective offenses. Given the unique history of discrimination against Black students, we draw attention to the substantial degree of subjectivity, discretion, and interpretation on the part of educational actors and school authorities in determining things like EC status, AIG status, punishment for (mis)behavior, and the meaning of subjective disciplinary offenses like disobedience, defiance, and insubordination. These determinations are in large part out of the control of Black students, as are many of the other indicators where they are disadvantaged, such as access to rigorous honors and Advanced Placement courses and numerous measures of access to effective teachers. This provides important context for our finding that Black students consistently have the lowest achievement results on EOG and EOC scores.

However, there are several indicators in our analysis where students and families do exercise a substantial degree of control, specifically attendance (chronic absenteeism) dropout/graduation, and postsecondary intentions. For all of three of these indicators, Black students have similar or better results than Whites and several other racial groups after controlling for factors like gender, socioeconomic status, language status, (dis)ability status, giftedness, and suspension. It is noteworthy that before controlling for those other factors, Black students compare poorly with Whites on all three metrics. This suggests that where Black students and families can exercise control over educational outcomes (attendance, dropout, college intentions), they demonstrate a strong commitment to success in school. However, their achievement outcomes appear to be constrained by disadvantages in access and opportunity, many of which are out of their control and vulnerable to the influence of racial prejudice and discrimination. Of course, this recognition has powerful implications for the experiences of Black students in North Carolina public schools, but we also highlight how it challenges the racialized discourse in education that often suggests that Black students/families, and other non-Asian students/families of color, are somehow less committed to success in school (Anderson, 1988; Jones, 2012). Indeed, our analysis strongly suggests the opposite, and that given equitable access and opportunity, Black students would likely make dramatic gains in achievement and attainment outcomes.

Pacific Islander

The results presented in this report provide some of the first empirical evidence of systemic racial inequity for previously unexamined or underexamined groups. As mentioned above, the small number of Pacific Islanders in North Carolina public schools led to non-significant results in roughly half of the indicators examined, making it difficult to fully assess their overall level of comparative advantage/disadvantage. However, among the significant indicators, all but one (suspension for subjective offenses) indicated disadvantage compared to White students. Given that trend, and the limitations of the data, is likely that our analysis underestimates the areas of disadvantage for Pacific Islanders. Furthermore, the state of North Carolina does not collect data on Pacific Islander teachers. This leaves a substantial gap in our understanding of the educational experiences of these youth.

American Indian

Our results show that American Indian students have among the highest degree of cumulative disadvantage of any group. Across the 44 indicators in Table 1, American Indians are disadvantaged in 38, including every indicator of academic achievement. They have comparative advantage in only 2 indicators (exceptional children designation and highly qualified teachers) and are similar to Whites in 4 indicators (in-school suspension, suspension for subjective offenses, dropout, and highly qualified teachers). American Indian students are the least likely to aspire to college, take the fewest honors and AP courses, and have the highest levels of chronic absenteeism. Their levels of out-of-school suspension are approximately double the rate of White students, and American Indians are among the least likely to take courses with ethnically matched teachers.

Taken together, our analysis of American Indians suggest that they may lack much of the structural support necessary for equitable levels of college and career readiness. As with other groups, attendance problems and over-selection for discipline likely diminish the achievement results of American Indian students. These disadvantages combined with decreased access to honors and Advanced Placement courses and few same-race teachers provide important insight into why so few American Indian students plan to attend college, despite their comparatively low high school dropout rate.

Multiracial

Multiracial students represent another underexamined student group. Given the complexity of their racial background, they are also perhaps the least understood of any student group of color, despite the fact that they make up a larger proportion of the student population than American Indians, Asians, and Pacific Islanders. The minimal research that has been devoted to Multiracial students has suggested that they are among the most vulnerable to accumulated disadvantage in educational settings (Triplett, 2018). Our analysis supports this conclusion.

Multiracial students are the only group in our analysis that is disadvantaged on every significant indicator of access, opportunity, and outcomes. Perhaps owing to the complexity of their racial identity, multiracial students do not represent the most acute levels of disadvantage in any single indicator. However, they do have among the highest levels of suspension, particularly suspension for subjective infractions. As is the case for Pacific Islanders, North Carolina does not collect data on teachers that identify as Multiracial, making it difficult to fully assess their exposure to effective instruction.

Hispanic

Although they appear to differ according to specific indicators, our analysis finds that Hispanic students in North Carolina public schools also have substantial accumulated disadvantage. Of the 44 metrics assessed, Hispanics are disadvantaged (vs. Whites) on 38, advantaged on four, and similarly situated on only two indicators. Three of the four metrics on which they have comparative advantage are related to school discipline (in school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and suspension for subjective offenses). This supports previous literature in suggesting that Hispanic students as a group experience school discipline in a less racialized manner than other non-Asian student groups of color (Gordon, Piana, & Keleher, 2000; Triplett, 2018). The final indicator with comparative advantage for Hispanic students (vs. Whites) is chronic absenteeism. This is not a surprising result considering that our analysis shows that suspension is such a powerful predictor of chronic absenteeism, even when we factor out absences due to out-of-school suspension. In other words, Hispanics’ comparative advantage (vs. Whites) on chronic absenteeism may be in large part due to their relatively low rates of suspension and the heightened levels of absenteeism among Whites.

Hispanics represent the group with the most acute comparative disadvantage on several indicators, including dropout, lack of same-race teachers, and judgmental exceptional children (EC) designations. The dropout rate among Hispanics is substantially higher than any other racial group in our analysis. While the data did not allow us to empirically test the relationship, it is perhaps not a coincidence that Hispanic youth drop out at such high rates in the absence of same-race role models in schools, particularly given the documented pressure that many Hispanic youth feel to pursue employment after high school (see Dropout).

Hispanics’ results on EC designations are also noteworthy. They do not have a particularly high likelihood of being designated EC in comparison to their proportion of the student population, but Hispanic results on EC demonstrate a unique pattern. First, there is a dramatic drop in the number of Hispanic EC designations when we use race alone as a predictor as opposed to when we control for other factors (i.e. gender, socioeconomic status, language status, (dis)ability status, giftedness). Secondly, as mentioned, Hispanics have the highest levels of judgmental exceptional children (EC) designations, which include the developmentally delayed, behaviorally/emotionally disabled, intellectual disability, and learning disabled designations. This may suggest that language status is inappropriately contributing to learning disabled EC designations for Hispanic students. While further study is required, if language status is contributing to EC in this way, it may indicate that school staff lack the resources needed to provide non-Native English speakers with the additional educational support they require and/or that school staff harbor biases that cause them to conflate lack of facility in English with learning disabilities.

White

While they serve as the comparison group in most of our analyses, our results still indicate comparative levels of (dis)advantage for White youth. With a single exception (Dropout/Graduation), Whites have a clear pattern of results on the indicators related to educational outcomes (EOC scores, EOG scores, GPA, ACT, SAT, and WorkKeys), such that they underperform compared to Asians but outperform all other student groups of color. White youth also tend to accumulate advantage with access and opportunity indicators. On 10 of the 21 indicators related to access, Whites are advantaged or similarly situated to all other groups. Results are mixed for the remaining 11 access indicators. The indicators where Whites compare most poorly to student groups of color are in-school suspension (ISS), chronic absenteeism, and dropout. While virtually all previous research has found that Whites are under-selected for discipline compared to non-Asian student groups of color, studies have also shown that all racial groups have similar misbehavior rates and that Whites tend to be punished less harshly than students of color for similar offenses (Finn, Fish, & Scott, 2008; U.S. Department of Justice & U.S. Department of Education, 2014). Therefore, our results for Whites on ISS may reflect a scenario where less punitive forms of discipline (in-school vs. out-of-school suspension) are rationed for Whites and more punitive forms of discipline are reserved for students of color despite similar rates and types of misbehavior (Welch & Payne, 2010).

More straightforward interpretations appear to apply to Whites and chronic absenteeism and dropout. Whites are over-represented statewide in chronic absenteeism compared to their proportion of the student population, but not in dropout. In our regression models, Whites tend to have much lower odds of both chronic absenteeism and dropout when race alone is used as a predictor. However, when we predict the odds of chronic absenteeism and dropout while controlling for other factors (Gender, Free/Reduced Lunch Eligibility, Language Status, Special Education Status, Giftedness, and Suspension), Whites compare to most student groups of color less favorably. This indicates that compared to similarly situated students of color, Whites exhibit concerning patterns of attendance and persistence to high school graduation. It is likely that attendance problems contribute to dropping out of high school for Whites (and other groups). Our examination of the reasons for dropout provide additional context for interpreting these results.

In addition to attendance, White students were more likely to cite substance abuse, health problems, lack of engagement with school/peers, unstable home environments, and psychological/emotional problems as reasons for dropout. These reasons were relatively unique for Whites, as other groups tended to cite discipline, child care, and the choice of work over school. Overall, our results may suggest that schools lack the structural supports needed to address the unique social, emotional, and psychological needs of many White students vulnerable to disengagement from school.

Summary and Findings, Notable Challenges, and Future Directions

Given the sum of our findings, the state of racial equity in North Carolina public schools should be a point of critical concern and sustained action for all stakeholders in education. Our core conclusion, that systemic barriers to access and opportunity feed educational disadvantage among student groups of color in our state, is a betrayal of the promise of public education. The urgency of fully understanding the matter at hand is further increased by the recognition that those responsible for educational policy and practice in North Carolina do not appear to regularly conduct comprehensive, action-oriented analyses of the state of racial equity intended to produce reform.

Two broad challenges follow from the results of this report. First, all student groups of color have inequitable access to the kinds of rigorous coursework and effective teachers necessary to ensure college and career readiness for all students. The challenges associated with rigorous coursework and effective teachers will require state-level, systematic intervention both because the relevant legal and statutory regulations are enacted on the state level and because equitable access requires policy reform that encompasses the substantial racial, cultural, geographic, and socio-political diversity of our state. Exposure to inequitable forms of school discipline represents a second major challenge. While there is considerable variation reflected in the disciplinary experiences of different student groups, we view discipline reform as a pressing challenge because of the powerful influence that over-exposure to suspension appears to have on critical outcomes such as attendance and dropout, and because the racialized patterns of discipline in North Carolina raise fundamental legal and human rights issues that reach far beyond the field of education.

Group-specific challenges flow from our analysis as well. Asian students reflect the same lack of access to rigorous coursework and effective teachers as other student groups of color. Data indicating that they are the highest achieving group makes them no less deserving of the conditions and resources necessary to reach their full educational potential. The pattern of results for Black students suggests that persistent prejudice and racism is still a key constraint on their educational success, especially in the areas of school discipline, exclusionary and judgmental exceptional children designations, and academically/intellectually gifted designations. It is important to reiterate the implied role that racial subjectivities (beliefs, opinions, biases, ideologies, etc.) of school authorities presumably play in these areas. We also call attention to the contribution our analysis can make to honoring the struggle and reinforcing the commitment of Black students and families to public education.

While Black students appear to have the largest magnitude of disadvantage on many indicators of access, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are disadvantaged across a higher proportion of metrics. While often of a different magnitude, the patterns of disadvantage for American Indian and Pacific Islander students suggests that they face many of the same barriers as Black students related to racial subjectivities. An overall lack of empirical research, and the educational community’s understandable and necessary focus on Black – White inequity, have likely contributed to a lack of clarity about how race influences the educational experiences of American Indian and Pacific Islander youth.

Multiracial students represent an even more extreme example of this. While they are perhaps the least studied and the least understood, they are disadvantaged on the widest collection of access metrics, and thus likely have among the highest cumulative disadvantage of any student group in the state. It is truly astonishing that the fourth largest student racial group has been relegated to little more than an afterthought in the discourse and policymaking in North Carolina.

While Hispanics as a group do not have the highest levels of cumulative disadvantage, our analysis reveals their unique pattern of disadvantage and the attendant challenges that they face. High dropout rates and a dramatic lack of Hispanic educators calls our attention to the relationship between the state’s commitment to a diverse and representative teaching corp and the educational success of its increasingly diverse students.

White students as a group tend to have the least amount of disadvantage across indicators of access and opportunity. With the exception of Asians, Whites also outperform students of color on virtually all indicators of academic achievement. This suggests that in general, White students likely have the benefit of structural supports that lead to educational success. However, our analysis related to dropout and attendance (chronic absenteeism) indicate that North Carolina schools may need additional resources and support in order to address the unique family, social, and psychological circumstances of White students and their communities.

The process of conducting an analysis across so many indicators and racial groups in the state has given us some insights into issues related to data quality. First, taking steps to collect and analyze data within racial groups would contribute to our empirical understanding of patterns of racial (in)equity. Specifically, further disaggregating race data within the Asian and Hispanic racial groups to include racial/cultural subgroups and country of origin for recent immigrants may allow research to parse the unique patterns of educational (dis)advantage for these groups. Doing so may help illuminate questions like: Why do Asians have such achievement success despite numerous structural disadvantages in access and opportunity? Why are there so few Hispanic teachers? Why do so many Hispanic youth leave high school despite relatively high aspirations to attend college? Answering these kinds of questions would increase understanding of the Asian and Hispanic experience but is also likely to bear on the educational journey of other student groups of color.

Our analysis also hints at a need for data that further encapsulates the geographic and regional diversity of the state, particularly in relation to White students. This kind of data could, for instance, help research better delineate between the experiences of rural, poorer White youth and their presumably wealthier urban and suburban counterparts.

There is also a clear need to collect data on teachers that identify as Pacific Islander and Multiracial. This is likely a simple matter of changing the options on a survey item. The lack of data on Pacific Islander and Multiracial teachers and administrators leaves a gap in our understanding of a critical predictor of educational success. In addition, state data on teacher qualifications includes a substantial proportion of teachers (~18%) with “unknown” qualifications. This makes it unclear whether any analysis of the relationship between teacher traits and student success (such as the EVAAS system) are valid. Unknown teacher qualifications take on additional salience today given policy discussions and proposals around such value-added measures.

Beyond the specific challenges discussed above, we believe the results of this report make it clear that the agencies and institutions responsible for fulfilling the mandate of public education laid out in the North Carolina Constitution and statutory law must demonstrate greater commitment to sustained attention, ongoing comprehensive assessment, and data-driven reforms to improve the state of racial equity in North Carolina public schools.

While policymaking bodies are ultimately responsible for the provision of a sound basic education and monitoring the performance of student groups in North Carolina, we contend it is necessary for a third non-governmental entity to take the lead by maintaining an intentional focus on race. Fortunately, racial equity has received increased attention as many stakeholder groups have adopted appropriate lenses when discussing the educational experiences of students. Racialized opportunity gaps require more intense scrutiny and action on the part of policy organizations and think-tanks. Now more than ever there is a need for an organization with the express purpose of measuring and responding to inequities in education across lines of race, not as a peripheral venture, but as a core strategy.

To that end, the parent organization that produced this report, the Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED), was created. CREED is committed to centering the experience of people of color in North Carolina as it transforms the education system for the betterment of all students. Taking a multi-pronged and purposefully multi-racial approach, CREED has three main branches of activity: Research, Engagement, and Implementation. Through research, coalition building, and technical assistance, CREED works to close opportunity gaps for all children in P-20 education, especially children of color, with the vision that one day race will no longer be a substantial predictor of educational outcomes.

To advance this mission, CREED conducts evidence-based research (the first of which are E(race)ing Inequities and Deep Rooted). Through partnerships with historians, researchers, and policy experts, we produce scholarship that allows for deeper and richer understanding of the issues facing students of color in North Carolina. In addition, CREED builds coalitions of school leaders, educators, parents, policymakers, and community members who have a shared agenda of creating equitable school systems. Through programming, communication and grassroots-organizing strategies, CREED is intent on shifting the atmosphere by providing the education and experiences needed to inform action in meaningful ways. Lastly, we support schools and educators with technical assistance and training designed to improve educational outcomes for students of color. As much as reports such as this one are instrumental in providing foundational knowledge about the myriad ways race influences our school system, direct service and professional development with practitioners is necessary for it to translate into sustainable change. CREED is committed to providing the sort of training and consultation that is often found wanting when engaging in issues racial equity.

In summary, our greatest contribution with respect to the findings of this report is to build an organization suited to respond to what we see. As things stand in North Carolina, no such entity exists that explicitly focuses on race, with interventions spanning the entire research-to-practice continuum. We hope this report may come to represent a watershed moment and believe organizations like CREED are best suited to take up the challenge of enacting racial equity in North Carolina public schools.

References

Anderson, J. D. (1988). The education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935. Chapel Hill, NC: University of of North Carolina Press.

Danico & J. G. Golson (Eds.), Asian American Students in Higher Education (pp. 18-29). New York: Routledge.

Finn, J. D., Fish, R. M., & Scott, L. A. (2008). Educational sequelae of high school misbehavior. The Journal of Educational Research, 101(5), 259-274.

Gordon, R., Piana, L. D., & Keleher, T. (2000). Facing the consequences: An examination of racial discrimination in U.S. public schools. Oakland, CA: Applied Research Center.

Jones, B. (2012). The struggle for Black education. In Bale, J., & Knopp, S. (Eds.). Education and capitalism: Struggles for learning and liberation. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Museus, S. D. & Iftikar, J. (2013). An Asian critical race theory (AsianCrit) framework. In M. Y.

Span, C. M. (2015). Post-Slavery? Post-Segregation? Post-Racial? A History of the Impact of Slavery, Segregation, and Racism on the Education of African Americans. Teachers College Record, 117(14), 53-74.

Staats, C. (2016). Understanding Implicit Bias: What Educators Should Know. American Educator, 39(4), 29-43.

Teranishi, R. T., Nguyen, B. M. D., & Alcantar, C. M. (2016). The data quality movement for the Asian American and Pacific Islander community: An unresolved civil rights issue. In P. A. Noguera, J. C. Pierce, & R. Ahram (Eds.), Race, equity, and education: Sixty years from Brown (pp. 139-154). New York, NY: Springer.

Triplett, N. P. (2018). Does the Proportion of White Students Predict Discipline Disparities? A National, School-Level Analysis of Six Racial/Ethnic Student Groups (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Charlotte).

U.S. Department of Justice & U.S. Department of Education. (2014, January). Notice of language assistance: Dear colleague letter on the nondiscriminatory administration of school discipline. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201401-title-vi.html

Welch, K. & Payne, A. A. (2010). Racial threat and punitive school discipline. Social Problems, 57(1), 25-48.

Editor’s note: James Ford is on contract with the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research from 2017-2020 while he leads this statewide study of equity in our schools. Center staff is supporting Ford’s leadership of the study, conducted an independent verification of the data, and edited the reports.