Editor’s Note: The University of North Carolina Academic and University Programs Division releases its annual report this week. Great Teachers and School Leaders Matter surveys the work of the Division and UNC’s fifteen educator preparation programs that are focused on the University’s goal of preparing more, higher quality teachers and school leaders for North Carolina’s public schools. EdNC will be highlighting the report’s profiles of teachers, school leaders, programs, and partnerships from across the state as part of a nine-part series. The full report is available here.

Yolonda Black knew from an early age that she wanted to teach; she just didn’t know exactly what that meant.

Yolonda grew up in Reidsville, North Carolina, where she first caught the teaching bug while watching her mother teach students from pre-kindergarten through grade 12 (she is still teaching today). Says Yolonda, “I always wanted to be a teacher because of the positive influence [I saw my mother] have on her students.” Yolonda knew that teaching was a lot of work for her mother, but she also saw how passionate her mother was about her job and decided, “I want to try that, too.” Not wanting to wait until she was old enough to take on teaching as a profession, as a child Yolonda would line up her stuffed bears in her bedroom and teach them.

Video: When did you first realize you wanted to be a teacher?

But entering the profession was not only about following in her mother’s footsteps. Equally as influential for Yolonda was the opportunity she knew teaching could provide for her to change the life direction of her students. Watching members of her own family struggle with education and finding success early in life providing advice to her peers helped her decide she wanted to be in a position to make school a better experience for as many children as possible.

And thus a teacher was born.

“I’m really good at teaching, I’m a natural at it,” she says with pride, but she also understood from the beginning that natural talent alone would not be enough. “As an 18-year-old, I had the vision, but I had to shape it, to mold it. I had to go through college to really understand what that meant. My general purpose was to become a teacher, but . . . [it is] my [student teaching] experience that has helped me to shape who I am as a teacher and what I want to do.”

A big part of that shaping has come at the hands of her instructors and mentors in the teacher preparation program at North Carolina Central University. Yolonda has been particularly thankful for the feedback she gets from her clinical supervisor, who has watched her grow throughout her final student teaching semester and who confirmed for her, after a recent in-class observation, that she is, indeed, a natural.

Video: How was your experience in North Carolina Central University’s Educator Preparation Program?

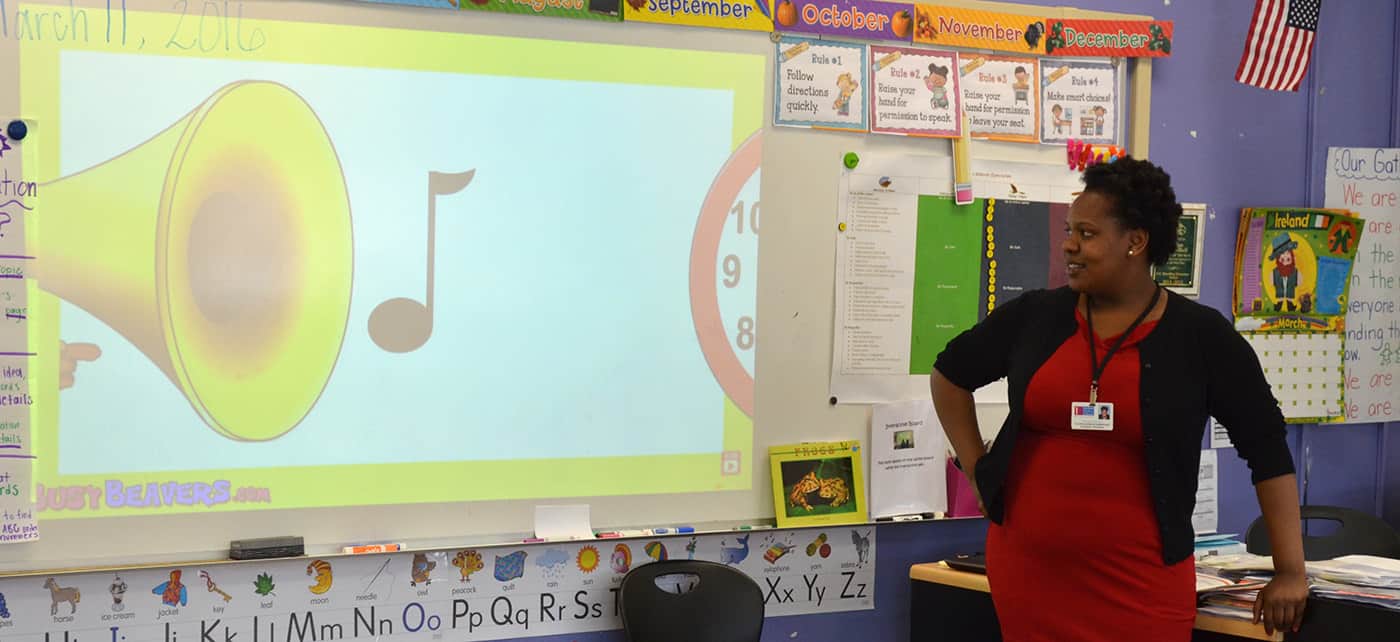

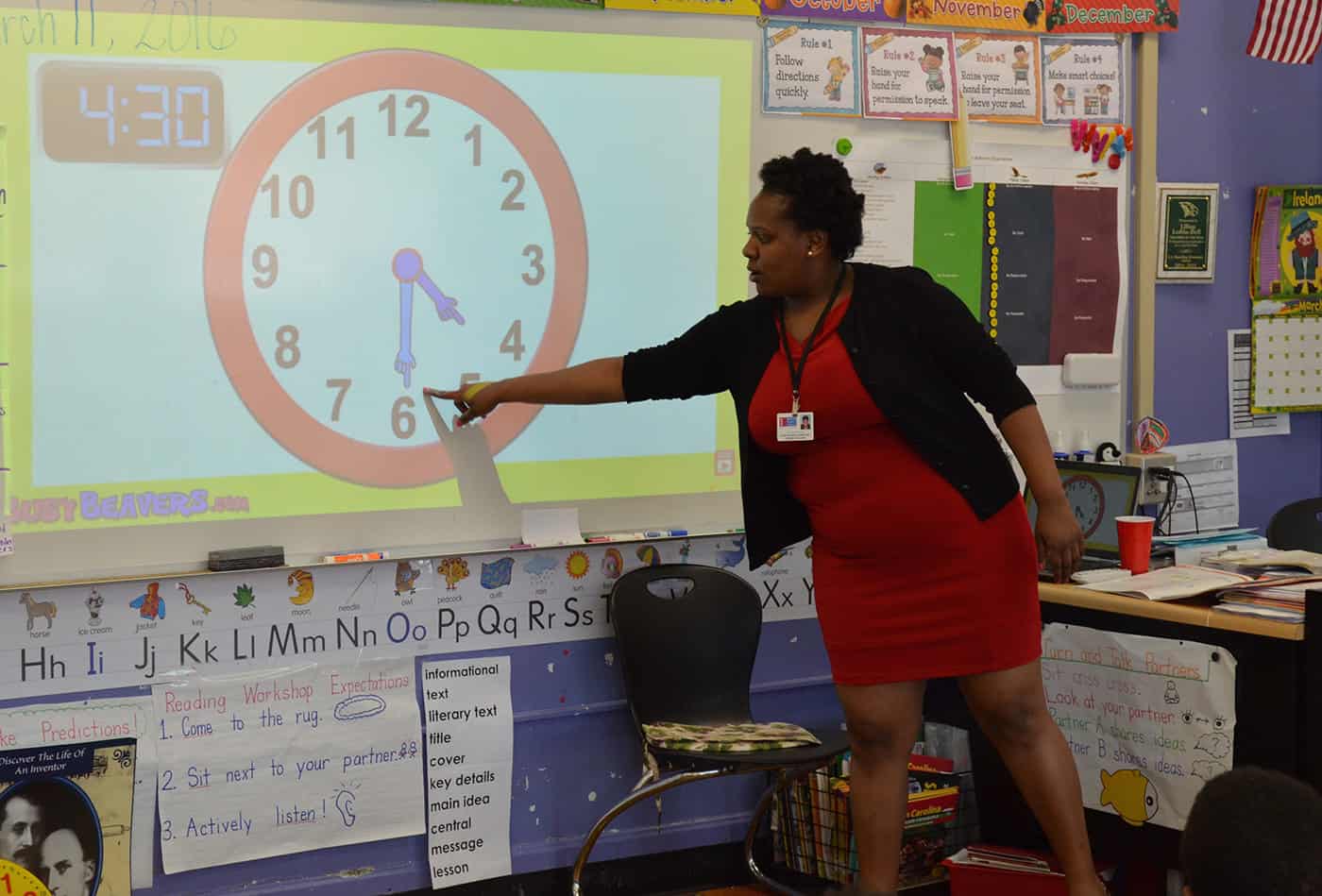

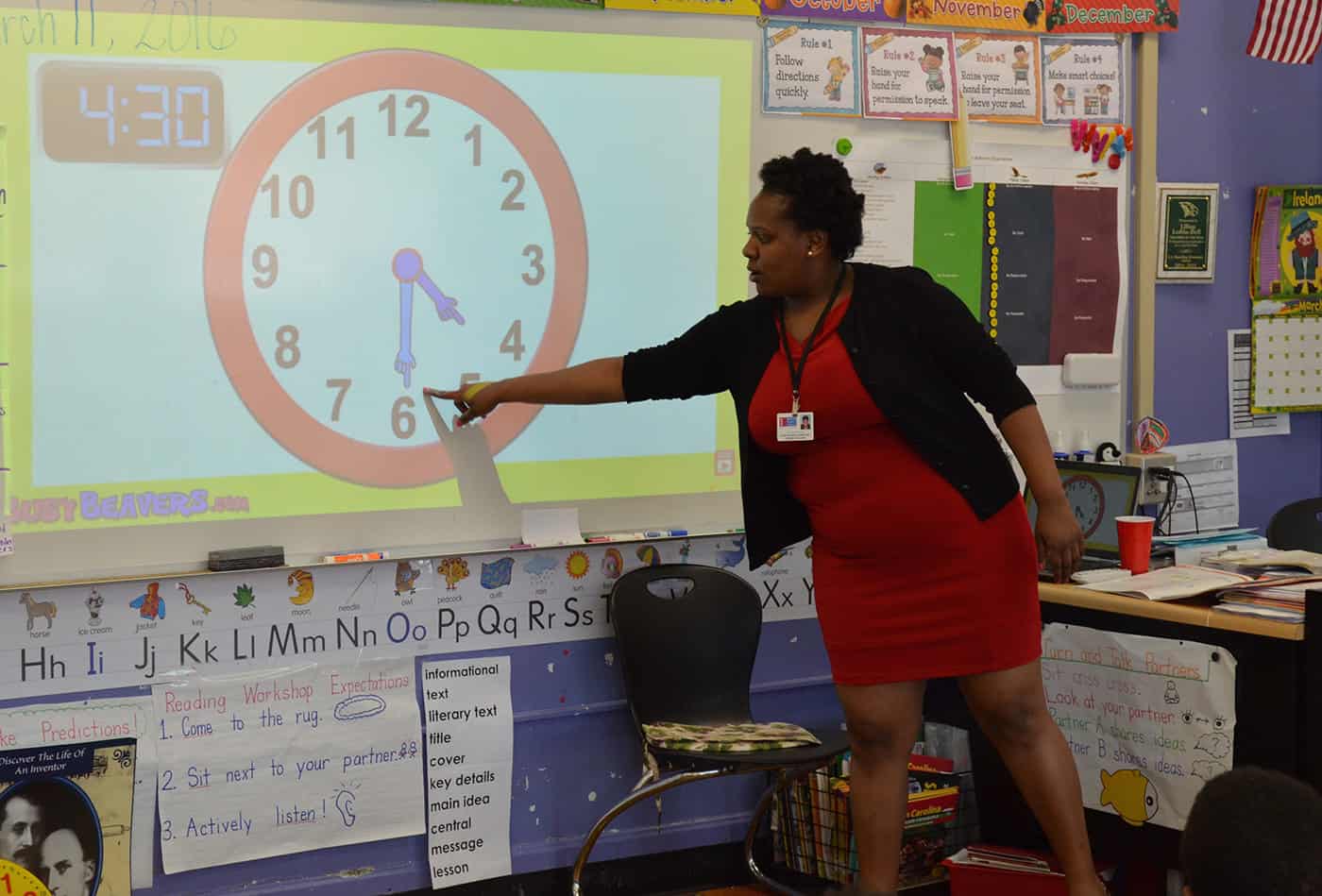

The support has come from her colleagues as well. One of the areas in which she has grown as a result of their support is in her ability to translate the advice she gets from other teachers into something that fits her personal style and that she can use in her own classroom. During one particularly challenging mathematics unit, she kept asking herself, “‘How can I break this down for them so that they can get it?’ So I asked other teachers and realized that I could give my students multiple strategies to choose from, and that worked.” She has paid back their investment in her with interest. Her cooperating teacher and many other teachers in her school all have come to recognize the value Yolonda brings to their school.

“I realized that day that I was really finally and fully myself as a teacher. I was really into it, and I was excited, because it was my classroom.”

After sharing resources from one recent successful unit, the entire team of first grade teachers at her school liked the projects she developed for her class so much they decided to use them, too. “That really helped me get through” some harder aspects of the student teaching experience, she confides. “Sometimes, the teachers even come in and ask me questions, [and that is] really rewarding.”

It all came together for her a few weeks into her final clinical experience when, for the first time, she had the entire class to herself for a full day. “I realized that day that I was really finally and fully myself as a teacher. I was really into it, and I was excited, because it was my classroom. I haven’t always had a chance to really project, to really be me out there, [but that day] was one of the best days I have had as a student teacher, and I felt afterwards that, when I have my own classroom, it will be an even better experience.” Yolonda knew lightbulbs were going on for her students that day when she saw them get really excited about learning. “I really love the kids, and they were excited to work for me. It’s a rewarding experience to see a child grow.” Realizations like that are what help a teacher make the transition from aspiring novice to young professional.

Despite her enthusiasm and innate ability, not everything about teaching has come naturally for Yolonda, but she knows that the struggles are as important as the successes. She is quick to point out that student teaching is “hard because you have to adjust to being in the real world . . . getting used to getting up early and completing an 8-to-5 work day,” but she contends that the experience has been well worth the adjustments she has had to make. In the beginning, “I was just so tired to the point where it felt like I couldn’t have a life outside of teaching, but I’m used to it now.”

Video: How essential are teacher preparation programs?

She also has a greater appreciation for all of the behind-thescenes aspects of teaching that were not as evident to an aspiring grade-school girl whose first stuffedbear “pupils” were perfectly passive receptacles. “You have to deal with a lot of outside issues [like student discipline and parents], and you also have to teach every subject every day in an elementary school. Handling all of that is, like, wow!” Dealing with student discipline can be the most frustrating for Yolonda, but she knows it is an important part of the teaching territory to which she will continue to adjust. “It drives me crazy sometimes. . . . I just wish I could go in there and teach, but that’s not teaching. That’s not reality.”

Finally, she notes that it has been hard at times as a student teacher to establish a teaching identity under the shadow of an accomplished cooperating teacher. In the end, though, she acknowledges that all of these challenges are just part of her growth: “I think the experiences will make me better when I have my own classroom.”

These and other challenges notwithstanding, Yolonda knows she made the right career choice, and her preparation has been a key ingredient in helping her find her teaching identity: “It has helped me realize what I really want to do.” As a result of her student teaching experience, Yolonda also now knows that part of her identity and purpose is much broader than just what she can do in a single classroom. “I know that I’m good at teaching, but I also know that I really want to do something that makes a difference in a school system. [This experience] really helped me shape my perspective and my purpose.” Her future? Teaching, yes, but also graduate school to pursue a master’s degree (and beyond?) in education— preferably concurrently, if she can work out the logistics, so that she delays neither continuing her own education nor getting into her own classroom.

As a result of her preparation, Yolonda does not perceive any limits. “I’m really good at being in front of people and talking . . . [and] breaking down information for people to help them understand it. I have a passion: I want [my students] to get [whatever I am teaching], so I ask myself, ‘What can I do to help them get it?’ I’m also very creative . . . very hands-on, and I like to incorporate technology. When the students walk in my classroom, I want them to be surprised, to not know what they are going to do that day and to be excited about it. That’s how I liked it when I was a student.”

She also wants to take what she has learned and use it to help shape educational opportunities for other minority students, to keep them from having the same experiences as some of her peers who succumbed to the challenges of school. She believes in the original mission of historically black colleges and universities of providing opportunities for students who would not otherwise have them, and she wants to help her students learn how to create the opportunities she has created for herself. “I don’t like to say I’m smart—I hate that word—I say I’m determined,” and that is the message she hopes to give to her students to motivate them to succeed. She intends to be there for her students long after they have left her classroom: “I don’t help people and then let them go; I keep checking on them to make sure they are still doing well.”

And that is the difference between just knowing naturally how to teach and embracing one’s personal teaching identity.

Great Teachers and School Leaders Matter Series

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Katie B. Morris

Part 3: Yolanda Black

Part 4: Jeff Vamvakias

Part 5: New Teacher Support Program

Part 6: Diana B. Lys

Part 7: Steve Lassiter

Part 8: Chase Schultz