“The best leaders . . . have it working on their guts and their hearts. Everybody needs to have a full chance, in Charles Bradley Aycock’s words, to ‘burgeon out all that is within them’. . . . At the end of four years, at the end of eight years, it isn’t going to be how much more money you put in, it’s going to be about the changes you brought about in schooling.” – Hunt

Education reform in North Carolina under Governor James B. Hunt, Jr. took a decidedly different path than had education reform in other Southern states. For one thing, Hunt remained at the helm of education reform efforts in the state for a considerably longer time than did his Southern gubernatorial colleagues, working as an elected official on education reform from 1973 through 1985, and again from 1993 through 2001. For another, while North Carolina did pass two omnibus education reform packages (one in 1985, shortly after the end of Hunt’s first two terms, and another in 1997, during Hunt’s third term), these bills were not the only significant reform packages adopted by the state but were instead part of a larger progression of education reforms big and small that had been evolving since Hunt’s term as Lieutenant Governor in the 1970s. Thus, Hunt’s education reform leadership was part of a much larger and slower-developing leadership cycle than was the case for most of the other members of his cohort of education governors.

Hunt’s first experiences working in education policy came in 1973, when he became Lieutenant Governor and the state’s highest-ranking Democrat. During his tenure as Lieutenant Governor, Hunt helped Governor Jim Holshouser to establish mandatory kindergarten and to implement teacher pay raises.1 In fact, it was Hunt and not Holshouser who had made kindergarten a campaign issue during his run for the Lieutenant post, along with teacher pay raises, bonuses for teachers with advanced degrees, and smaller teacher-pupil ratios. The kindergarten plan reached 15,000 students in its first year (1973), and soon after, it evolved into the first all-day, universal kindergarten program in the country.2

Education reform during Hunt’s first term

Hunt made the transition from the lieutenant governor’s office to the governorship in 1977. Once there, Hunt “made a major effort to dominate and guide the state legislature during his first two terms in office,” and he did so in part by drawing up immediately after his election what he would in later terms refer to as an “Agenda for Action,” a short list of action items on which he wanted every member of his administration to focus.3 The creation of the agenda became a common practice followed by other North Carolina governors in subsequent years.4 He also actively pursued ratification of significant institutional changes to the office of the governor. It is almost a certainty that none of the Hunt education legacy would have been possible without his successful lobbying for a constitutional amendment that many of his predecessors had supported but that had never passed: an amendment that would allow governors to succeed themselves, which was passed during Hunt’s first year in office. Hunt believed that passage was made possible in part by the fact that the amendment would apply to him personally.5

Finally, also during his first year, Hunt anticipated a key strategy important to his fellow education governors when he began a steady campaign of creating ways for the general public to be involved in the policy process. His first step was to create an Office of Citizen Affairs, which was charged with promoting citizen awareness and participation in government. He also instituted weekly press conferences during his first two terms.6 By the end of his fourth term, Hunt had become the modern-day North Carolina champion for making public appearances, averaging 221 a year during his first term, 369 a year his second term, 291 his third, and a staggering 506 his fourth.7

“The most important power of the governor . . . is public leadership, public education, the bully pulpit. . . . When I went out as I did so many times and had town meetings about education in schools, I would talk about our statewide Smart Start initiative. I’d talk about our effort to raise standards for teachers and raise pay to the national average. I would talk about our accountability system and all that. But I would take it right down to that school, to that county, that city. Get people talking about what they were doing, getting them thinking about how they can advance these ideas and move this agenda ahead. . . . People need to know their leaders. They need to feel that they are acting, that they are leading, and, from seeing that happen, participate in some way with it. I believe that gives people a greater sense of purpose and involvement and more ownership of the democratic process.”8

At the start of his first term as governor, Hunt used his 1977 State of the State address to call for $15 million for special reading aides, testing in early grades, and minimum graduation standards. All of these proposals passed during the 1977 summer session.9 The reading program for grades 1 through 3 – the Primary Reading Program – which had been part of a campaign promise, placed reading aides in every classroom.10 His “Raising a New Generation” early childhood program, however, did not gain much traction and would not see the light of day again until its reincarnation as the better-planned Smart Start program during his second two terms. Ferrel Guillory notes that the original plan was too centralized for most legislators’ tastes, perhaps crossing the fine line between what the state would and would not allow in terms of state-level control, while its distant relative Smart Start allowed for more local control.11

The minimum graduation standards bill serves as a good example of the hands-on approach Hunt often employed to secure passage of education proposals. He personally proposed the legislation, hand-picked the representatives who would sponsor the bill, and stayed involved with the bill’s movement through various committees and hearings. His recruited allies included Democrats and Republicans, educators and non-educators, and representatives from the western and eastern parts of the state. He also benefited from the hard work of the first of many competent legislative liaisons, Charles Winberry.12

Despite the legislative success, however, the program proved to set a standard that was too high for many schools to meet quickly. In April 1978, after abysmal first-year results from the minimum competency tests, Hunt approved a Competency Test Commission, which proceeded to ease the standards.13 By 1983, however, under Hunt’s leadership, North Carolina would again raise graduation requirements and start the North Carolina Scholars Program.14

Hunt’s second State of the State address in 1979 called for greater attention to remedial education, a strengthening of vocational education offerings, and the establishment of the North Carolina School of Science and Math (NCSSM).15 Bills supporting all of these agenda items were passed during the 1979 session.16

Reframing and expansion during the second term

Hunt’s second term (1981-1985) was dominated by what would become his rallying cry in the years that followed: reforming education to ensure economic prosperity.

“Why are you doing it? There are two reasons. One is human beings deserve it. What are we put on this earth for? And second, we want to have economic growth and prosperity and an opportunity for our children. Those are the two main driving things.” – Hunt

Hunt’s linkage of education and the economy was made first during the 1976 campaign.

At one point during that campaign, when asked what his economic development plan entailed, Hunt answered simply, “Education.”17

Indeed, Wayne Grimsley, Hunt’s first biographer, often characterizes Hunt’s emphasis on education reform as solely or primarily a tool for promoting his economic growth plan for the state.18

In October 1983, partly in response to a shift in the state’s manufacturing sector that required more skilled labor, Hunt formed and chaired the North Carolina Commission on Education and Economic Growth (CEEG),19 which drew up An Action Plan for North Carolina and presented it to the General Assembly. Reflecting not only the Commission’s name but also the general thesis of education reform in several Southern states, the report sought “‘to ensure that new generations of North Carolinians will reach the higher general level of education on which sustained economic growth depends.’”20 The report laid out several general areas for reform – creating broad partnerships committed to reform; improving curricula; raising the status of the teaching profession; increasing the quality of school leadership and management; and addressing the needs of special populations, all with an anticipated price tag of $300 million21 – and included such specifics as calls for better teacher training and salaries and the hiring of more teachers to reduce class sizes.22 Like several other Southern governors before and after him (e.g., William Winter in Mississippi, Richard Riley in South Carolina), Governor Hunt tasked the Commission with holding four public fora across the state – in Raleigh, Asheville, Greenville, and Charlotte – to elicit input from citizens.23

The group’s plan was transformed in the General Assembly into what would become known as the Basic Education Plan,24 which included a promise to increase overall state funding for schools by 34 percent over several years, an increase in not only the number of teachers but also of support personnel (like librarians and social workers), class size reduction, and improvements to summer school and vocational education programs.25 Specific elements of the BEP included:26

- Increased public involvement and support for education;

- Enrichment and improvement of the basic curriculum in every school – a basic course of instruction common to every school and a more rigorous set of standards for promotion and graduation;

- An increase in the status of teaching, as well as in the (monetary) rewards for teachers and administrators – a Career Development Program also was to be piloted in 16 districts;

- Improvement of the learning environment in schools – including class size reduction and increased funding for textbooks, supplies, and equipment;

- Improvements in education leadership – including the development of “model schools;”

- Enhancements in special needs and gifted programs; and

- Enhancements in services for underserved populations and potential dropouts.

Overall, the BEP was structured to include an eight-year phase-in (i.e., by 1993) and would involve the addition of over 24,000 new jobs (almost half of which would be teaching jobs), at a cost of about $870 million.27

Though the BEP was clearly a product of the Hunt administration, the omnibus education plan did not pass until Hunt’s successor, Republican Governor Jim Martin, was in office.28 The legislature responded favorably to the BEP, increasing operating funds by over 24 percent during the 1985-1986 session (though they did not approve teacher pay raises).29

Momentum from eight years of reform

The 1987-1988 legislature continued the funding for BEP and added a School Facilities Construction Act for new buildings and renovations of older ones; funding dropped off, however, during the 1989-1990 and 1991-1992 sessions, mostly due to state revenue shortfalls.30 In 1988, the Public School Forum, a Raleigh-based education group, released Thinking for a Living: A Blueprint for Educational Growth, the development of which was supported in part by the North Carolina Citizens for Business and Industry. The nearly $720 million list of almost 80 recommendations – largely centered on accountability measures – received the blessings of both then-Governor Martin and former Governor Hunt.31 The document was transformed by the state in 1989 into the School Improvement and Accountability Act,32 which included the Performance Based Accountability Program (PBAP), a voluntary statewide end-of-grade testing program that provided the framework for what would later (during Hunt’s third term) become a mandatory statewide testing program. Every district elected to participate.33

Hunt was re-elected governor in 1992 and would go on to serve for another eight years. In Hunt’s third and fourth terms, arguably more productive than his first two in terms of education legislation passed, he ushered through: Smart Start (1993), the long-delayed descendent of the Raising a New Generation program from years earlier;34 the Excellent Schools Act (1997), which included a teacher pay increase, bonuses for advanced degrees, incentive awards based on school performance, and higher standards for teacher certification; and changes to the Standard Course of Study – renamed the ABCs of Public Education – that included a transition from the voluntary PBAP to a required testing program that is still in existence today.35 Hunt’s strategies for getting bipartisan support for his Excellent Schools Act in 1996 and 1997 might be thought of as his graduate thesis on controlling the education reform arena, a thesis developed during his first two terms.

Also during Hunt’s third term, a new norm that had been making much headway across the nation over the previous two decades – the importance of equitable distribution of resources for education – became a factor in education reform in North Carolina. Starting with Serrano v. Priest (Serrano I) in 1971 and reaching an apex with Rose v. Council for Better Education (Rose v. Kentucky) in 1989, there had been a national push toward more equitable statewide education funding, and this push resulted in North Carolina in the filing of the Leandro suit in 1994.36 The impact of this emerging norm on Hunt’s approach to education reform is perhaps best evidenced by his 1996 re-election platform plank that once again sought to raise the average teacher salary.37

Hunt’s last major education reform idea while still governor, the “First in America” campaign, which aimed at achieving high rankings for North Carolina on several education issues by 2010, was begun during his final year in office.38

The Governor has continued to be a presence in education reform at both the state and national levels since leaving office in 2001.

“I found, and I have always found, that the way to make it work is to run on it, tell the people what you’re planning to do, and let them say, ‘We want to do it.’ When you get elected, it isn’t your idea, it’s their mandate.” – Hunt

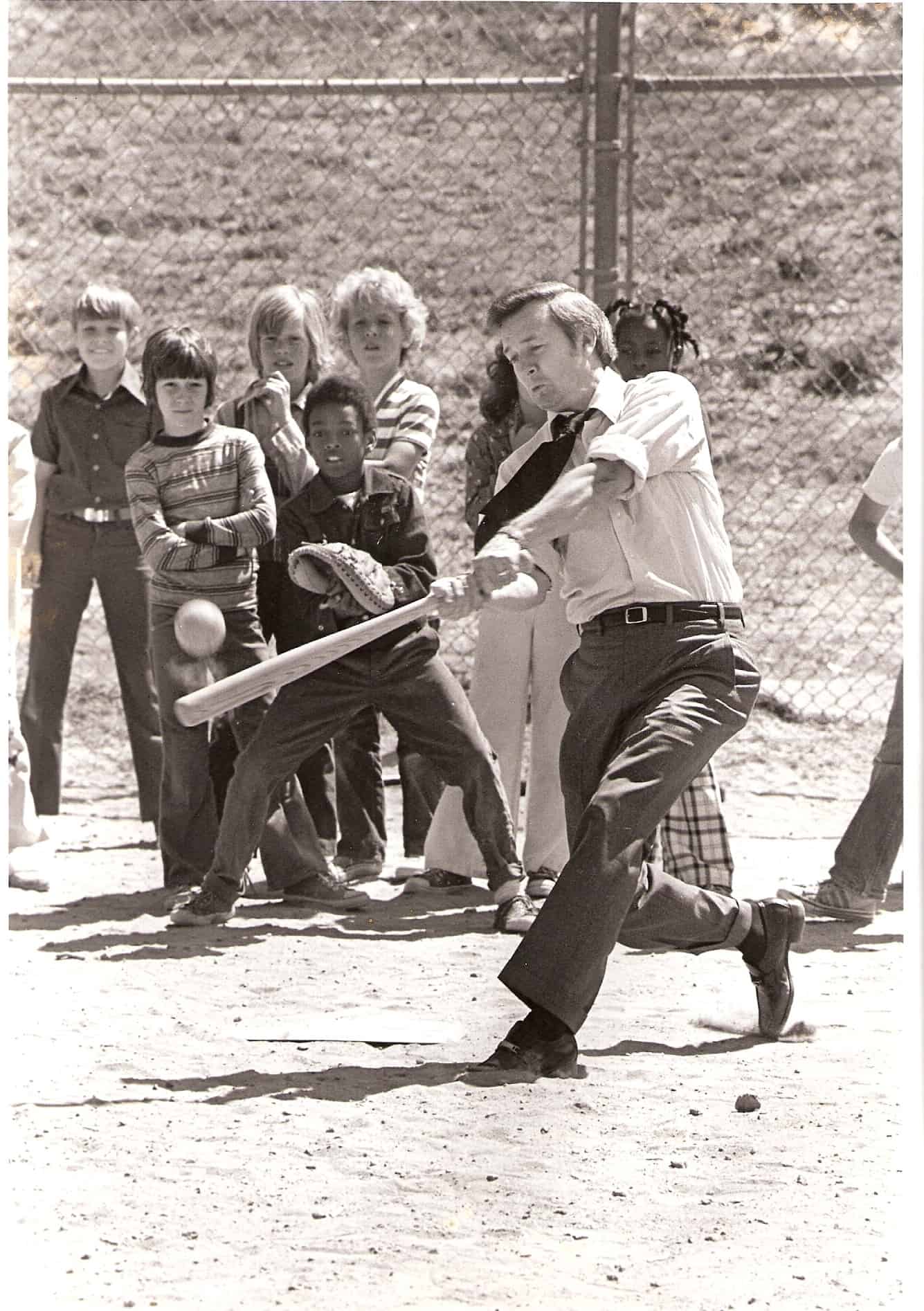

EdNC thanks you, Governor Hunt, for knocking it out of the park for our children.

References

Excerpted from THE GOVERNORS’ CLUB: EXAMINING GUBERNATORIAL POWER, INFLUENCE, AND POLICY-MAKING IN THE CONTEXT OF STATEWIDE EDUCATION REFORM IN THE SOUTH, 2010

Beckwith, R. T. (2007). Jim Hunt. Under the Dome. The Raleigh News & Observer Online. Retrieved July 21, 2008, from http://projects.newsobserver.com/under_the_dome/profiles/jim_hunt

Christensen, R. (2008). The paradox of Tar Heel politics: The personalities, elections, and events that shaped modern North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of Chapel Hill Press.

Diegmueller, K. (1992, December 16). Like Clinton, N.C.’s Hunt trains spotlight on schools. Education Week. Retrieved September 16, 2008, from: http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1992/12/16/15hunt.h12.html

Fleer, J. D. (1994). North Carolina government and politics. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Fleer, J. D. (2007). Governors speak. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Grimsley, W. (2003). James B. Hunt: A North Carolina Progressive. Jefferson, NC: McFarlane & Company.

Guillory, F. (2005). Education governors for the 21st century. Chapel Hill, NC: The James B. Hunt Institute for Educational Leadership and Policy.

Heady, K. (1984). Making connections: Education, training, and economic development in the South. Research Triangle Park, NC: Southern Growth Policies Board.

Luebke, P. (1998). Tar Heel politics. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Manzo, K. K. (2001, January 10). Dean of education governors departs. Education Week. Retrieved September 25, 2008, from: http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2001/01/10/16hunt.h20.html

McColl, A. (2001). Leandro: Constitutional adequacy in education and standards-based reforms. School Law Bulletin, 32(3), 1-21.

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NC DPI). (2001). History of the North Carolina State Board of Education. Raleigh, NC: Author.

Poff, J. (Ed.). (1987). Addresses and Public Papers of James Baxter Hunt, Jr., Governor of North Carolina. Volume II. Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources.

Rash Whitman, M. (1996). The right to education and the financing of equal educational opportunities in North Carolina’s public schools. In M. Rash Whitman and R. Coble (Eds.), North Carolina FOCUS: An anthology on state government, politics, and policy (pp. 121-141). Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research.

Recommended reading