Editor’s Note: The University of North Carolina Academic and University Programs Division releases its annual report this week. Great Teachers and School Leaders Matter surveys the work of the Division and UNC’s fifteen educator preparation programs that are focused on the University’s goal of preparing more, higher quality teachers and school leaders for North Carolina’s public schools. EdNC will be highlighting the report’s profiles of teachers, school leaders, programs, and partnerships from across the state as part of a nine-part series. The full report is available here.

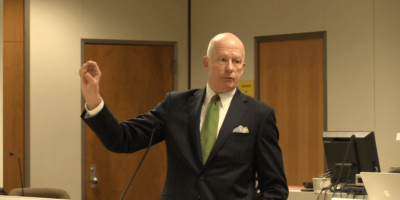

Five minutes with the 2015 Wells Fargo North Carolina Principal of the Year Steve Lassiter are enough to persuade you that he is a person of great energy and personal initiative. His brilliant smile and obvious articulate enthusiasm for education tell you that right away. But the story of Lassiter’s path to Pitt County’s Pactolus Elementary School and the pinnacle of the principalship is not one of personal initiative alone. It is also the story of a whole series of encounters with challenges in an ever-broadening series of arenas and with other educators who inspired, encouraged, and supported his development into an outstanding leader in the eyes of his colleagues across North Carolina.

Lassiter’s experiences as a student growing up in his beautiful hometown of Edenton convinced him that he wanted to be a teacher like those who had given him “a great education.” He would be the first in his family to pursue a college education, and initially he planned to attend the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, halfway across the state. But “at the last minute” he realized that he wanted to stay closer to home and enrolled at East Carolina University instead.

Nor would that be the last course correction in his path to the principalship. After aspiring initially to teach mathematics, Lassiter turned toward elementary education, completed his coursework, served his internship in nearby Winterville, and turned his sights again to the west, expecting to pursue a master’s degree at Appalachian State University. But his path branched again when his principal impressed him with the need for more African-American representation in the Pitt County Schools and asked him to stay, shifting from third to fifth grade. At that point, Lassiter’s entrepreneurial spirit showed itself: “I told him I would stay and make the shift if he would hire my friend to teach fifth grade with me.” An interview convinced the principal that Lassiter’s friend would further strengthen his school’s fifth grade offerings, and the two enjoyed a successful year, cooperating in preparing and revising lessons.

Lassiter’s path took another turn after he realized that he really wanted to concentrate on a single subject. But this time it was language arts, not mathematics. That would require a move to the middle school, considered by many the most challenging level of students to manage and teach.

Inspiration, Recognition, and Encouragement

It was there that Lassiter was inspired by the example of Principal Delilah Jackson, “the model of what it meant to be a good leader. If I were ever to leave the classroom,” he recalls, “this is somebody that I aspired to be. I’d like to have professional conversations with staff members like her. I’d like to conduct meetings like her.”

Jackson, Lassiter said, was always open and honest in her conversations with staff. Perhaps unconsciously following Jackson’s lead, he recalled quite openly a discussion with her that was painful for him personally. Many students in the school were children of “doctors, attorneys, prominent state employees, and others in the upper echelon of Pitt County,” and Lassiter found it difficult to adjust to parents who wanted to be so intimately involved in the details of their children’s education. When the time came for his annual evaluation, Jackson told him that “everything is above standard except this one,” the standard concerning communication with parents and the community. Looking at him levelly, she said, “I want you to work on this standard. You are going to be phenomenal in this district one day, and I don’t want this one thing to throw you off course. If you work on this, I guarantee, you’ve got it.”

Seeming a little pained even now, Lassiter said, “As hurt and offended as I was, I could see later that she was right. And that’s what good leaders do. They’re able to see and tap into the hidden potential of the people they serve, and not be afraid to make a course correction and help you re-chart your course and do better. She snapped my ego and got me started in a new direction.”

“And that’s what good leaders do. They’re able to see and tap into the hidden potential of the people they serve, and not be afraid to make a course correction and help you re-chart your course and do better.”

Lassiter went on to recall other examples of Jackson’s leadership. For example, “She gave us tips on how to relate to our African-American students who came from a large project here in the district. She’d say, ‘I’m not going to support putting students out on the streets. We’re going to support our students. We have to engage our students while they’re here because we may be the only adults that they have a positive interaction with throughout the day.’”

Not long after Jackson’s reputation took her to another level within the district, Principal Julie Carey, her replacement, came to him and said, “Steve, you need to think about becoming a principal.” Carey may have been responding not only to the quality of Lassiter’s teaching, but also to the leadership he had taken on at his own initiative within the school, showing his colleagues how to integrate technology into their instruction, serving as chair of the School Improvement Council, and writing grant proposals to bring in additional resources for the school.

Video: How do you know a teacher has the potential to be a leader?

The interest was there, but the money and time to pursue a master’s in school administration (MSA) were not. Fortunately, a colleague who had been through the legislatively funded NC Principal Fellows Program encouraged Lassiter to apply: “Steve, you really need to go after this fellowship. You’d definitely be good.” Although he was reluctant to give up the satisfactions of teaching, “I could see that I could have a much broader impact. As a principal, I could help 25 or even 50 teachers in a building to perfect their craft instead of working in my one classroom.” The NC Principal Fellows Program provided tuition, preparation, and a stipend to allow Lassiter to devote his full attention to his preparation for the principalship.

Master of School Administration Program: Coursework

Lassiter’s successful application enabled him to enter the MSA program in East Carolina University’s Department of Educational Leadership. The MSA courses that Lassiter recalls as most helpful in preparing him to serve as a school leader all shared one characteristic: they were intensely practical and case-based, built around real challenges taken from the experience of principals in schools like those Lassiter would later lead. Dr. Hal Holloman’s course left a particularly strong imprint in Lassiter’s mind. “He used scenarios in nearly every class session. Here’s the situation. Now what do you say to this person? What is it you’re going to say when a teacher who has been absent for two weeks comes into your office and tells you she’s been having cancer treatments? When a student comes into your office and discloses something really bad that has happened with a parent. What do you say about those things? I am just so grateful that I had that course with Dr. Holloman, because he really taught us what it means to be a servant leader – leading from the heart and making sure you are saying to your staff, ‘What can I do to help you?’ I still do that every day. I walk around the building and I ask, ‘What can I do for you?’”

“I am just so grateful that I had that course with Dr. Holloman, because he really taught us what it means to be a servant leader – leading from the heart and making sure you are saying to your staff, ‘What can I do to help you?’ I still do that every day. I walk around the building and I ask, ‘What can I do for you?’”

Lassiter also recalls Dr. Kermit Buckner’s class in school law, which piqued his interest in human resources and personnel. As Holloman did, Buckner worked from specific challenging situations. “You would have to present your response and justify it based on reasoning from previous cases in the law.” Dr. David Siegel’s course made a lasting impression as well. “It was really intense. You would have to write responses to complex cases – eight or ten pages – making sure that your response was well-informed, with evidence to support the way you handled the situation. At one point, I wasn’t sure I was going to survive that course, but it turned out to be a really good experience.”

From Lassiter’s point of view, a key part of many of these case-based classes was the opportunity to compare and discuss his responses to the cases with other students. For example, one case dealt with a problem arising from the African-American Students’ club at a high school. Some other students took offense at the exclusiveness of the club. Asked how he would handle this problem, one MSA student proposed to shut down the club altogether. Another objected that this response would also be discriminatory. A third said that to avoid discriminating, he would just shut down all student clubs. A fourth challenged that proposal, arguing it would deprive all of students of valuable extracurricular learning opportunities. “That led to a big argument, and some of it got pretty hot, but in the end, we all learned a lot from that. Our professors didn’t shy away from really touchy issues, because they’re part of what principals have to deal with on a daily basis.”

Master of School Administration Program: Internship

The second year of East Carolina University’s MSA program consisted primarily of an internship in which Lassiter served for four days a week as assistant principal of an elementary school in Pitt County. The fifth day was devoted to further coursework. Experience as an assistant principal “… really prepared me to be a school leader. I had to see and deal with all of the different facets of leading a school – Individualized Educational Program meetings with parents, student discipline, curriculum and instruction, setting up and adjusting the master schedule, recruiting, guiding, and evaluating teachers, services for Academically or Intellectually Gifted students, special education services, books, office staff, the cafeteria, janitorial services… there are just so many things to pay attention to, not just the students in your classroom.”

Fortunately, Lassiter says, the leadership of the MSA program recognized that preparation for the principalship was not solely a matter of acquiring new knowledge and skills, but also making a fundamental transformation of mindset. “From day one, we were told, ‘Hey, guys, you’ve gotta take off that teacher hat. You’re no longer a teacher. You can’t just think about your 25 students. You’ve got to start thinking in terms of what’s best for 600 or 700 kids and 20 or 30 teachers. They were definitely right about that.”

During the internship, Lassiter received guidance not only from the principal with whom he was serving, but also from East Carolina University faculty advisors, who visited the school on a regular basis and from faculty who taught the final coursework one day per week.

Enriched Opportunities for NC Principal Fellows to Learn

In addition to coursework at East Carolina University, the NC Principal Fellows Program provided a variety of enriching experiences organized by the program’s central office in the Academic and University Programs Division of the University of North Carolina General Administration, including seminars on specific topics in school law or dealing with diverse students. Of particular value were opportunities to hear from and interact with practicing principals from across the state – especially principals who turned around low-performing schools at one level or another.

Video: How important was the Principal Fellows Program to your career?

Now that he is a practicing principal himself Lassiter “gives back” by speaking to each incoming class of NC Principal Fellows, providing them with advice on how to take maximum advantage of the opportunities the Fellows Program and their MSA programs will provide them. And he helps to cap off the Fellows’ experience with a final address at graduation.

Current Challenges and Opportunities

As 2015 North Carolina Wells Fargo Principal of the Year, Steve Lassiter has a new set of challenges and opportunities: he serves as an advisor to the NC State Board of Education and Superintendent of Public Instruction June Atkinson. As he closes his term as NC Principal of the Year, Lassiter is committed to speaking for the needs and interests of schools and school leaders: “There is a piece missing when it comes to our General Assembly,” Lassiter says, “and that is hearing the voices of people who are in the trenches, doing the work of educating students every… single … day. We address teachers but not principals, and those two just cannot be separated. So when we advocate for teachers to have raises, for example, we should also advocate for principals to have raises. That’s my campaign for the rest of the year, advocating for our school leaders, and helping people to realize that if you find a great school, the research will show there’s gotta be a great leader there.”

“That’s my campaign for the rest of the year, advocating for our school leaders, and helping people to realize that if you find a great school, the research will show there’s gotta be a great leader there.”

“And we have to restore respect for the profession. As someone who is in the trenches, I’m telling you, teachers are leaving because they don’t feel valued, and there are only so many things I can do as a principal until my teachers decide that they’re leaving teaching to go on to the next thing in their lives. And we can’t pit our beginning teachers against our veteran teachers by giving raises only to the beginning teachers. Because if the veterans are not there, who’s going to mentor the new teachers? Who’s going to bring them along?”

Summing Up

As our interview with him drew to a close, Lassiter grew quiet for a moment, then offered a summation of what he stands for:

“I will always openly support my staff. I will never do anything to tear them down, publicly or privately. But privately, I am not afraid to have a conversation about things that we just need to correct. Often leaders are just so afraid of backlash – whether it is community backlash, board member backlash, or parents. But if you know that it’s right and it’s in the best interests of children, then you have to act anyway. Of course, the question is when is the time to actually do it. Timing is everything. And so I live by that every day. If there is something I need to address with a staff member, I take notes as to what I want to say, I’m thinking about it to make sure I’m saying it in the right way, because it has to be said for children. I’ve heard it said that principals are always just one decision away from losing their job, because it could be that one decision and — you’re done. But if you can stay true to the mission and vision of your school and your decisions can be made and justified on that basis, you can’t be afraid to make those good decisions in the interests of your children.”

Not a bad credo for a Principal of the Year. Or any other principal.

Great Teachers and School Leaders Matter Series

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Katie B. Morris

Part 3: Yolanda Black

Part 4: Jeff Vamvakias

Part 5: New Teacher Support Program

Part 6: Diana B. Lys

Part 7: Steve Lassiter

Part 8: Chase Schultz