ON THE FIRST DAY of every semester during my five years as a teacher at Garinger High School, I had a candid talk with my students about how the world perceives them. The school, sitting off of Eastway Drive in east Charlotte, is high-poverty, majority-minority, and distinctly urban. I knew, from my own experiences, exactly what “type” of school this was, and I didn’t shy away from telling the kids.

I told them that many people didn’t expect much from their population, because of where they live and what they look like. That they all fit into somebody’s stereotype. I told them that students who go to a school such as Garinger are less likely to graduate than students elsewhere. I told them it was a setup of sorts. Then I waited, reading the responses on their faces. Some pouted, sulking in a sense of internalized low self-worth. Others were visibly angry, as if I had confirmed something they never had the language to articulate.

I should say here that my teaching experience at Garinger was amazing. I enjoyed my students and labored passionately to ensure they received a great education. I even became the North Carolina Teacher of the Year. But I knew what was happening from the first day I arrived on campus.

This school, home of the Wildcats, was a symbol of our local system’s backward trend toward re-segregating along racial and socioeconomic lines—a startling shift for a system that, just a few decades ago, was the district referenced in the landmark Supreme Court case Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, a system that was once regarded as the vanguard of school desegregation.

At the end of that speech on the first day of each semester, I informed the students of the purpose of my presence: That I knew what it was like to be doubted and mistreated. That I was on a mission to make sure they broke out of this destructive system. That I needed their trust before I could teach them. Far more often than not, they gave it to me.

But the truth is, no educator should have to have that conversation with his or her students—ever.

I AM THE PRODUCT of an integrated schooling experience in a school system that was otherwise highly segregated. This was not the result of masterful planning as much as good fortune, combined with some parental advocacy. I am a black man who grew up in a city that was recently ranked as the second-worst city in the country for African Americans. Rockford, Illinois, proved extremely hard for a child of color in the 1980s. It’s a mid-sized, industrial city in the heart of the Midwest. The river that runs through the middle of town doesn’t just separate east from west; it divides access to opportunity. Each side of town is characterized by specific demographics that follow a general pattern. The east side: largely white, middle and upper class, and prosperous. The west side: mostly black and Latino, working and lower class, and destitute. There are exceptions, but the rule is typically proven.

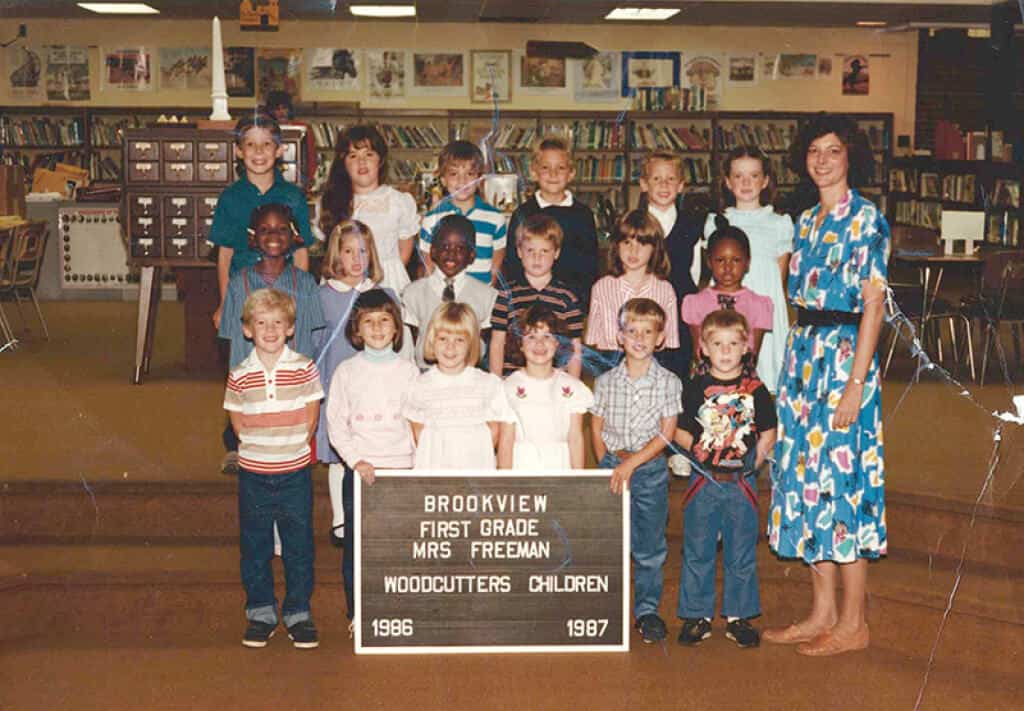

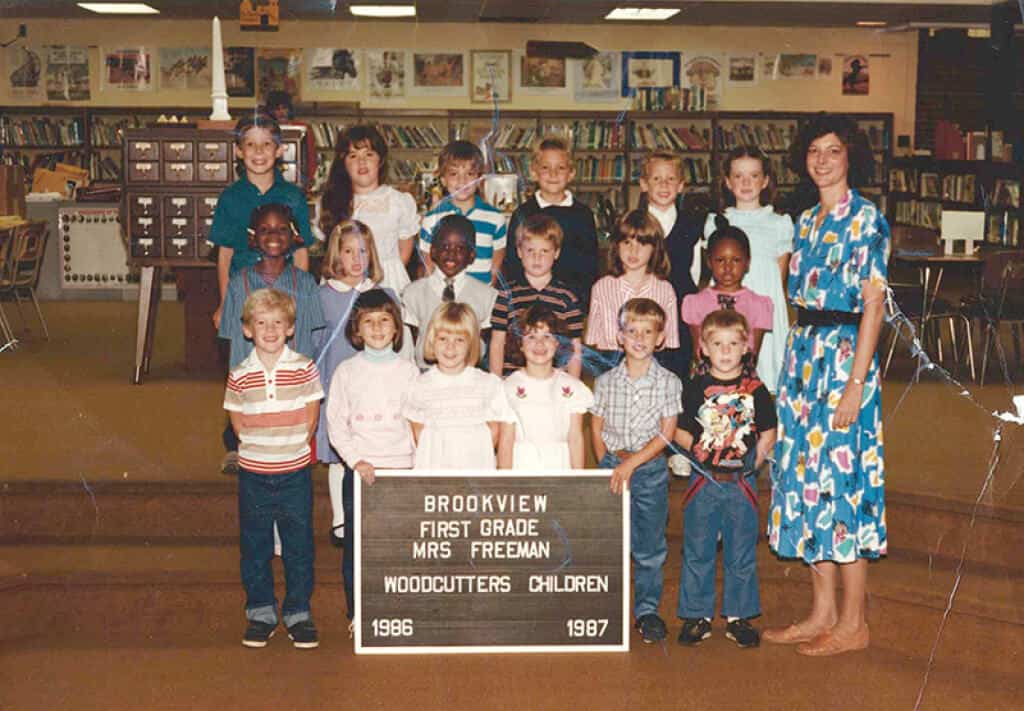

My older sister and I endured a twisted route to school. Located in an affluent corner of east Rockford was Brookview Elementary. It was academically superior to my neighborhood school. I, along with my sister and a handful of other black children from across the river, was bused there beginning in first grade. This was a halfhearted effort by the school district to comply with the 1954 desegregation order from the U.S. Supreme Court, albeit a purposefully minimalist approach. We woke up early in the morning so our parents could take us to a child care center on the east side. We’d then board a bus from there to school. Most of my neighborhood friends continued to attend racially homogeneous schools. My parents exploited a provision in the student assignment policy that allowed students to attend any school, so long as their addresses or day care providers were in proximity to the school.

At Brookview, I had to learn very early how to endure insults, slurs, and persistent mistreatment and rejection from both classmates and staff. I had a few scuffles as a result. At age five, I learned the meaning of the word “nigger” from classmates who didn’t hesitate to use it in reference to me. I don’t recall having much discussion after it was said. I just remember tearing up and going into a blind fury. Somehow, the child who insulted me wound up on the ground.

I remember a little girl in class who kept making interesting comparisons. She turned to our fellow classmates and asked, “Which is better, a black dog or a white dog?” She paused, and then answered, “Clearly, the white dog is better.” She followed up, “Do you like vanilla ice cream or chocolate ice cream?” She insisted that “everyone knew” vanilla was superior. Even as a child, I knew we weren’t talking about puppies and desserts. Moments like these left an indelible mark on my psyche, but they made me stronger.

Despite all of this, the sad reality is that I was receiving a better education than I would have at my neighborhood school. The halls were clean, the class sizes were small, the school had a newspaper run by parents, and we even put on a bona fide annual school parade through the neighborhood. This was a side of life I had never known. The majority of my teachers were kind, highly regarded, and had been fixtures there for years. Though it was difficult, I learned how to make some friends and eventually adjusted to the name-calling.

I can openly acknowledge I would not be the person I am if it weren’t for the exposure granted me through desegregation.

THINGS CHANGED DRAMATICALLY for me and other children of color after 1989. The Rockford Board of Education was sued by a local parent organization called People Who Care, alleging that the board had been intentionally discriminating against black and Latino students. After years of litigation, Federal Magistrate Judge P. Michael Mahoney in 1993 concluded the school district had “consistently and massively violated the dictates of Brown v. Board of Education” and had done so with “such subtlety as to raise discrimination to an art form.” Consequently, desegregation orders were given more oversight and teeth. Among the things that emerged from this period was an arts magnet program called Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA). It was housed in the city’s one middle school and one high school on the west side. The schools operated as partial magnets, and the program was audition-only. Fortunately, my siblings and I got in.

CAPA was a place unlike anything I had ever seen: rich with cultural texture and diverse students whose commonality was our creativity. I also loved the fact we were in west side schools that had been labeled as “bad.” My teachers were unconventional individuals who loved kids. I have never been around more interesting, talented, and eccentric people at any period in my life. One of the first people I met was David. He was a thin, blond-haired white boy with an asymmetrical haircut like a skateboarder. David had the initials “P.E.” shaved into the side of his hair. He told me it stood for “Public Enemy.” My eyes lit up. This had to be the only white boy I had ever met who listened to hip hop, especially Public Enemy! We talked about our favorite acts—N.W.A, De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest—and were friends from that point on. I share this not to tokenize him, but to demonstrate the bonds forged. Many of them last to this day.

In this space, I was allowed to be me— to rap, to dance, to joke, to have fun without being seen as different by my peers. I imagine this is what integration is supposed to feel like. Today, I consider my educational environment and the relationships born from it part of my wealth. My classmates helped to shape my being, by doing nothing more than being themselves. It was a cultural exchange. I didn’t have to bend or shapeshift when I was around them. Because of my schooling, there is rarely a space in which I feel out of place, even when others try desperately to put me there.

AS THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG school system revisits the school assignment plan, we are gifted with the chance to help bring an end to the conversations I had to have with my Garinger students. But first, we must wrestle with the fundamental question, “Who are we?” Are we a community that responds to the needs ofevery student and values the benefits of integrated schools? Or are we a community that just talks about the idea of fairness, while simply accepting inequities in the name of self-interest? Our actions will determine the true nature of our collective character. In this way, student assignment is causing a crisis of identity.

Those who oppose desegregation offer plenty of reasons why it won’t work. Arguments centered on children of privilege instead of children of poverty abound. Some even disregard the usefulness of inclusion altogether. Yes, the conversation may well devolve into more xenophobic notions that appeal to our worst assumptions about other people. (The nowfamous This American Life series “The Problem We All Live With,” which aired last year on NPR, reveals just how ugly the discussions can get.) But we must work through this process, because we cannot afford to get it wrong.

I stand as a personal testament: Although there is no cure-all for inequality, desegregation is a part of the solution. And study after study shows that the worst fears about negative effects on white and affluent students are overwhelmingly unfounded. These fears develop in the first place because we are segregated. When folks don’t live around different people, when they don’t go to school or have meaningful interactions with different groups, they will naturally slip into negative generalizations.

Consider the following:

“Segregation did not exist to hold back [N]egroes. It existed to protect us from them. And I mean that in multiple ways. Not only did it protect us from having to interact with them, and from being physically harmed by them, but it protected us from being brought down to their level[…]The best example of this is obviously our school system[…] But what constitutes a ‘good school’? The fact is that how good a school is considered directly corresponds to how [w]hite it is[…]The pathetic part is that these [w]hite people dont [sic] even admit to themselves why they are moving. They tell themselves it is for better schools or simply to live in a nicer neighborhood. But it is honestly just a way to escape [blacks] and other minorities.”

That’s an excerpt from the online manifesto of Dylann Roof, the shooter allegedly responsible for the deaths of nine people in a Charleston church last summer.

Although Roof took his views to extreme and barbaric measures, they are similar in substance to many of the coded appeals we hear in public discussions. We can no longer pretend to give our children a world-class education in schools that don’t look like the world. The purpose of education is not just to enrich the mind; it is also to make a more cultured person. As America becomes more brown, the question is not just whether or not we want integrated schools, but do we want to live in an integrated society? Are we an inclusive or exclusive community?

The answer depends on how we see ourselves.

This article was originally published in Charlotte Magazine on January 4, 2016. EdNC extends its sincere thanks to Charlotte Magazine for permission to reprint.

Editor’s Note: James Ford is on the Board of EdNC.