On Aug. 20, educators, business leaders, policymakers, and philanthropists gathered in Durham for the North Carolina Chamber’s annual Education and Workforce Conference. The conference focused on the new statewide attainment goal of two million high-quality credentials or degrees by 2030 and what it will take to achieve that.

Speakers included Jim Hansen of PNC Bank, Vance County Superintendent Anthony Jackson, and Susan Gates from SAS, who spoke on the importance of expanding NC pre-K to 75% of all eligible children. Breakout sessions featured collaborative partnerships between business and education, including the STEM East Network and K-64 in Catawba County. The event concluded with a panel of North Carolina’s education system leaders, who reiterated their commitment to increasing attainment through both degrees and credentials.

As I listened to the speakers, one thing stuck out to me — with the exception of Shaw University President Paulette Dillard, none of the speakers spoke to the role of race and ethnicity in attainment. The release of a new report on racial equity in North Carolina’s K-12 public schools highlights the fact that if North Carolina is serious about achieving its attainment goal, it must do so with an explicit focus on racial equity. In other words, we can’t talk about attainment without talking about race.

The state of racial equity in North Carolina’s public schools

On August 11, the Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED) released a report examining racial equity in North Carolina’s K-12 public schools. The report, authored by James Ford and Nicholas Triplett, uses data from 1.5 million students during the 2016-17 school year to examine over 30 indicators of access and achievement by race and ethnicity. These indicators include chronic absenteeism, drop out rates, suspensions, honors and Advanced Placement courses, grade point averages, North Carolina end-of-course and end-of-grade exams, and more.

The report paints a disturbing, though not surprising, picture of racial inequities across access to educational opportunities that inevitably result in inequitable educational outcomes. In short, North Carolina is not preparing its non-Asian students of color for college or career. Here are a few highlights from the report.

Access to experienced teachers and teacher racial/ethnic match

As the report notes, teacher quality is hugely important in students’ success: “Teacher quality has been consistently identified as the most important school-based factor in student achievement.” The report measures teacher quality by qualifications, experience, racial/ethnic match, and turnover/retention.

The good news is that over 80% of North Carolina’s teachers in 2016-17 were highly qualified and just 0.5% were not highly qualified (the other 18% had no determination of quality). The analysis found that Pacific Islander and Asian students have the highest exposure to unqualified teachers and Hispanic, black, white, and multiracial students all have similar levels of exposure to unqualified teachers.

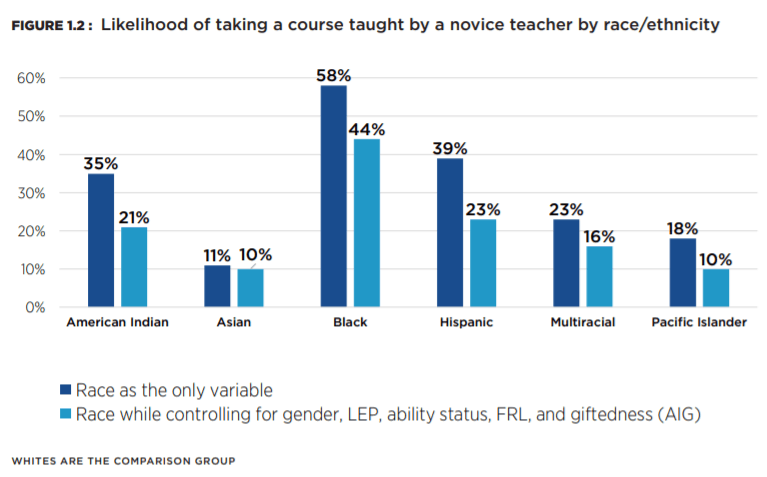

The data on novice teachers (teachers with three or fewer years of experience) tells a different story, however. The report finds that all student groups of color, especially black students, are significantly more likely to have novice teachers than white students, even after controlling for other relevant factors.

Interestingly, when they examined the distribution of novice teachers across schools, the researchers found that schools with higher proportions of students of color did not have higher shares of novice teachers, leading them to conclude that the sorting of students of color into classes taught by novice teachers is happening within schools.

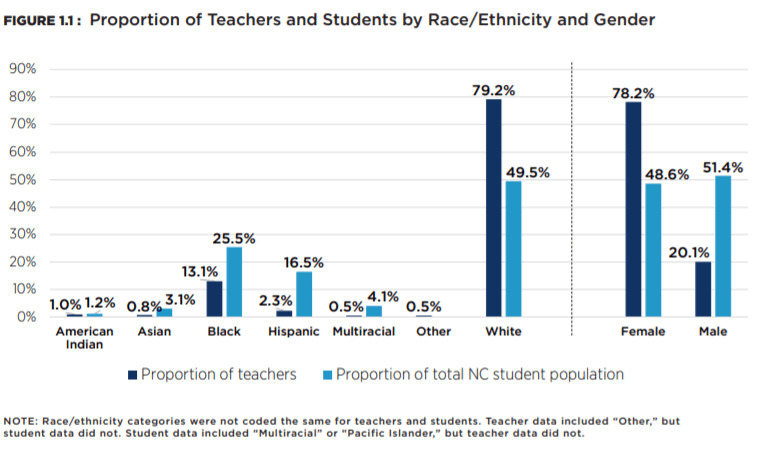

Finally, the report highlights a persistent problem across the country — the lack of teacher diversity compared to student diversity. North Carolina’s teaching force is roughly 80% female and 80% white whereas the student population is only about 50% white and 50% female. The gap between the Hispanic teacher population (2.3%) compared to the Hispanic student population (16.5%) is particularly striking.

Given the evidence showing the positive impact of having a teacher of the same race/ethnicity on student achievement, these results demonstrate an urgent need to recruit and retain teachers of color.

Access to advanced coursework

What is unique about this report is that it doesn’t just look at inequitable outcomes. It also looks at the structures that either support or limit access to educational opportunities. A perfect example of this is the analysis of honors courses and Advanced Placement courses.

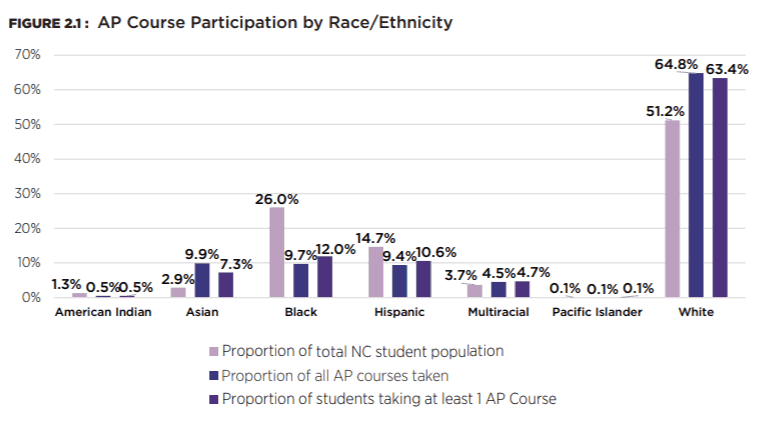

According to the report, non-Asian students of color are under-represented in the share of students taking both Advanced Placement (AP) and honors courses. For AP courses, black students comprised just 9.7% of all students taking AP classes in 2016-17 although they comprised 26% of high school students. On the flip side, Asian students comprised 9.9% of all students taking AP courses although they only made up 2.9% of the high school student population.

This same pattern holds for honors courses: Asians and whites are over-represented in the share of students taking honors courses while black, Hispanic, American Indian, and multiracial students are under-represented.

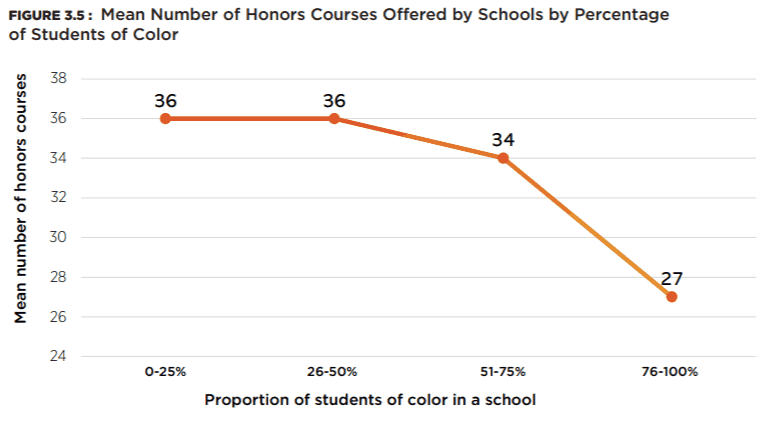

One possible explanation for this is that for whatever reason, these groups are on average less prepared to take advanced coursework in high school than white and Asian students. When you take a closer look, however, you see another factor at play: schools with higher proportions of students of color offer fewer AP and honors courses than schools with a smaller share of students of color. The data on honors courses is especially pronounced.

Lacking access to advanced coursework like honors and AP classes has a whole host of negative consequences for students. Not only are students not exposed to more rigorous coursework supposed to prepare them for postsecondary education, but they are more likely to have lower grade point averages (GPAs) because they do not receive the “quality point” bonus that students receive for taking honors and AP courses (see page 74 of the report for more on how schools calculate GPAs). Colleges and universities give significant weight to GPA in their admissions decisions, according to the report, so lacking access to advanced coursework directly impacts students’ ability to pursue postsecondary education.

The ripple effects of school discipline

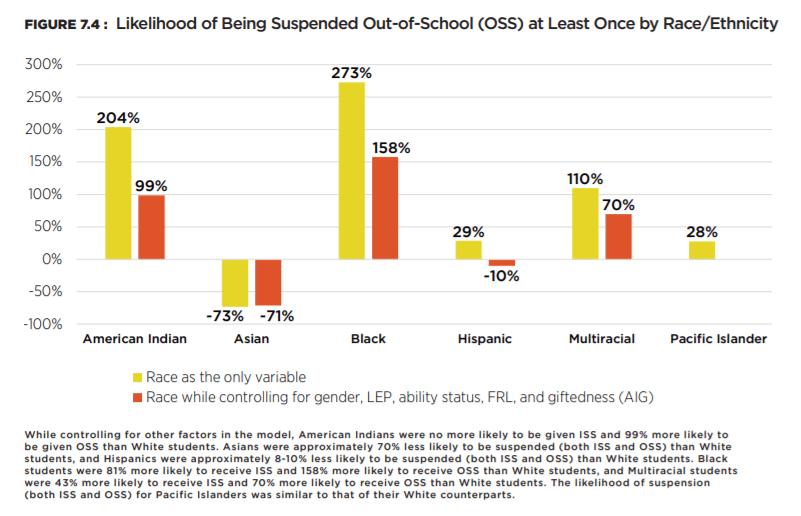

The report highlights another school-based factor that has significant consequences for students of color in North Carolina: discipline. The data clearly shows that students of color, particularly black and American Indian students, are disproportionately suspended (both in-school and out-of-school) compared to their share of the student population. After controlling for other relevant factors, the analysis found that black students were 158% more likely to receive out-of-school suspension at least once compared to white students. American Indian and multiracial students were also much more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions than white students.

It should come as no surprise that being out of school impacts student achievement, but it goes beyond just achievement. The report analyzed chronically absent students, or those who missed 10% or more school days during the 2016-17 school year. Importantly, they did not include days suspended in the count for chronic absenteeism.

Their analysis found that students who had received out-of-school suspension at least once in the 2016-17 school year were 350% more likely to be chronically absent than those who had not been suspended (remember that days suspended were not included in the count). Being suspended out of school was the strongest predictor of chronic absenteeism of any of the factors in the analysis, including race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Being suspended also increased the likelihood of dropping out of high school. The analysis found that students who were suspended at least once during the year they dropped out were 230% more likely to drop out than those not who were not suspended.

The path to two million by 2030

Beyond the moral obligation to our students of color, North Carolina’s changing racial demographics make it clear that any path to two million high quality credentials or degrees by 2030 must address these deep, persistent inequities in our education system. North Carolina’s constitution guarantees every child the opportunity for a sound basic education, but it is clear that the state has fallen short. Hopefully the data in this report can provide a starting point to work toward that promise.

Editor’s note: James Ford is on contract with the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research from 2017-2020 while he leads this statewide study of equity in our schools. Center staff is supporting Ford’s leadership of the study, conducted an independent verification of the data, and edited the reports.