This article is excerpted from a full paper that is available as a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper.

A defining characteristic of charter schools is that they introduce a strong market element into public education.

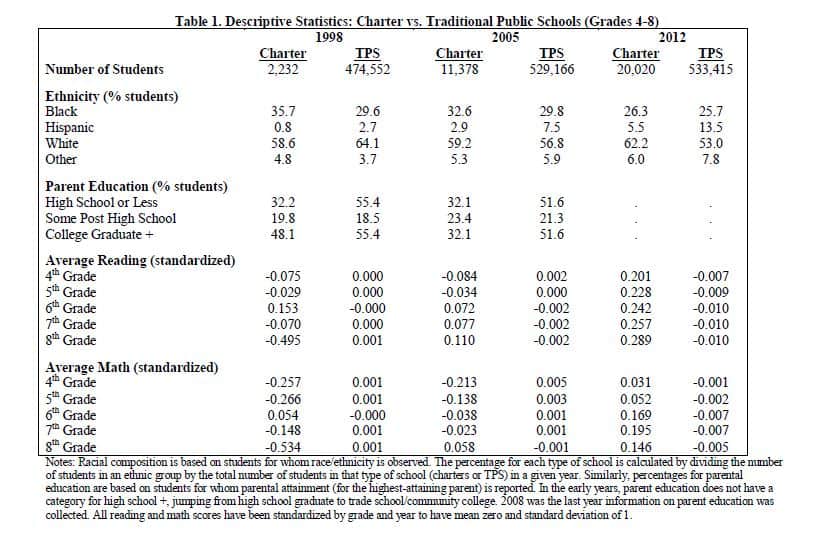

First, we find that the state’s charter schools, which started out disproportionately serving minority students, have been serving an increasingly white student population over time.

We have examined the evolution of the charter school sector in North Carolina between 1999 and 2012 with attention to three market-related considerations. First, we find that the state’s charter schools, which started out disproportionately serving minority students, have been serving an increasingly white student population over time. In addition, during the period, individual charter schools have become increasingly racially imbalanced, in the sense that some are serving primarily minority students and others are serving primarily white students. The resulting market segmentation in the charter school sector reflects a major difference between charter schools and the typical textbook version of a private sector market. In the case of schools, consumers—in this case, parents—care not only about the quality of a school’s program but also the mix of students in the school. As a result, market forces will tend to lead not only to more satisfied consumers, but also to market segmentation, which in the case of schools is typically by the race of the student.

Second, we find that, as would be predicted, the quality of the match between parental preferences and the offering of the schools is in general higher for charter schools than for traditional public schools…

Second, we find that, as would be predicted, the quality of the match between parental preferences and the offering of the schools is in general higher for charter schools than for traditional public schools, where our proxy for match quality is the demographic-adjusted proportion of parents who keep their children in the charter school the next year relative to similar parents whose children are in traditional public schools. Importantly, however, we conclude that the charter school parents whose children are enrolled in predominantly white charter schools are more satisfied than those whose children are in predominantly minority charter schools. Although we have no way to test explicitly for motivation, this difference in apparent satisfaction is consistent with the view that many white parents are using the charter schools, at least in part, to avoid more racially diverse traditional public schools.

…now charter school students tend to have higher test score gains than those attending the traditional public school…

Third, we document that the charter schools as a group initially started out behind the traditional public schools in terms of the test score gains of their students. Over time, however, the distributions across schools in the two sectors converged and now charter school students tend to have higher test score gains than those attending the traditional public schools. This finding reflects in part the winnowing out of charter schools whose students performed poorly, and, in recent years, the entry of schools whose students performed better, a process that is consistent with predictions that market forces would drive under-performing schools out of business. The apparent success of the charter schools entering after 2006 has likely been enhanced by a policy change in that year that required charter schools to delay opening for a year after their charter was approved, and the associated support provided by the state’s Office of Charter Schools during and after that year.

An additional explanation for bigger achievement gains among charter school students would focus on the changing clientele of charter schools.

Our analysis of the changing mix of students who enroll in charter schools over time leads us to believe that a major factor contributing to the apparent improved performance of the charter schools over the period may have as much or more to do with the trends in the types of students they are attracting than in improvements in the quality of the programs they offer. Our analysis of changes over time in the prior-year test scores of the students entering charter schools in grades 6, 7 and 8, for example, shows a dramatic shift over time: In the early years, the new students in charter schools tested at lower levels than their peers who remained in traditional public schools, but, by the end of the period, the new charter school students were apparently far more able (as measured by their prior year test scores) than their peers who remained in the public schools. At the same time our analysis of student achievement using student fixed effects shows that charter schools are no more effective than traditional public schools in raising the achievement of students who switch into public schools. Hence, we conclude that the apparent gains in the test scores of charter school students over time have far more to do with selection than with the quality of the programs they offer.

Taken together, our findings imply that the charter schools in North Carolina have become segmented over time, with one segment increasingly serving the interests of middle class white families.

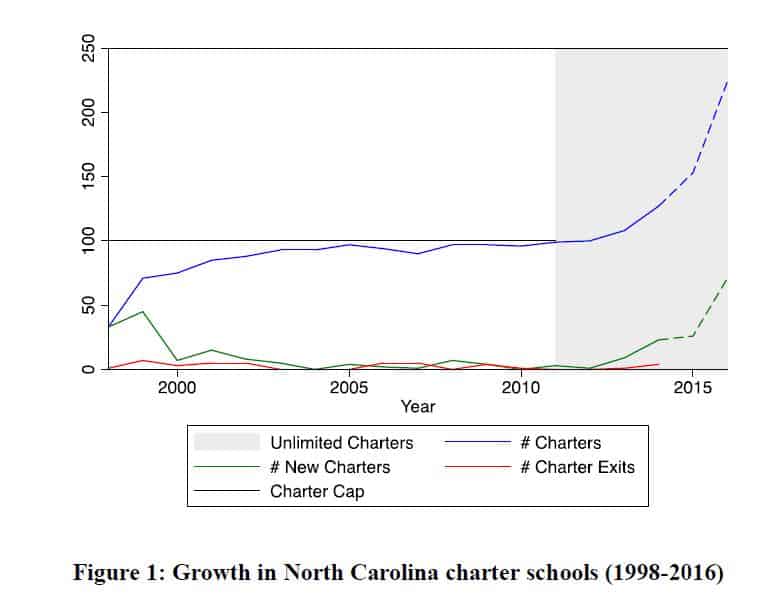

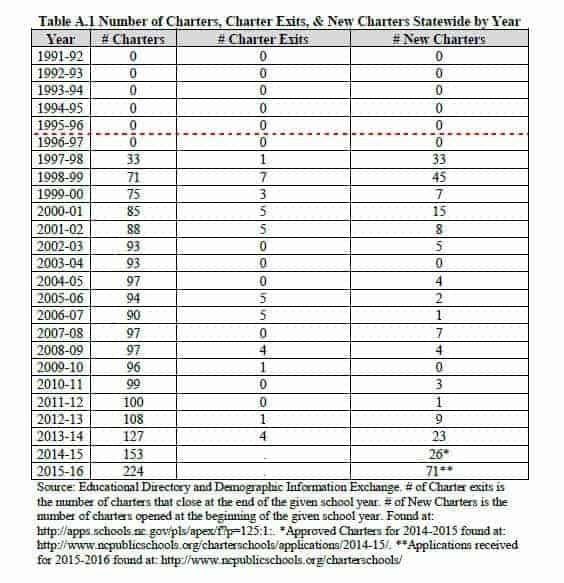

Moving forward, the charter school sector in North Carolina is likely to grow significantly, although probably not as fast as its proponents would like.

Moving forward, the charter school sector in North Carolina is likely to grow significantly, although probably not as fast as its proponents would like. On the one hand, the 2011 removal of the 100-school cap, the 71 applications for new charters in 2014, and legislative changes that make it easier for existing charter schools to expand without specific approval all point to large increases in the size of the sector over the next few years. On the other hand, by recommending that only 11 of the 71 new charter applications be forwarded to the State Board for approval, the Charter School Advisory Board has put a bit of a damper on the rate of growth, at least in the short term. Not happy with this outcome, however, the Legislature has now approved a “fast-track” option for charter school operators that have experience operating successful schools and want to replicate them. Such schools would not have to go through the typical planning year, and could open months after their approval at the start of the following academic year. As the state’s charter sector grows, we would expect to see a continuation of the trends that we have documented here, with the possibility that new entrants may once again struggle as the proliferation of new schools exceeds the limited capacity of the Office of Charter Schools to oversee and support them during their start-up periods.

We have said nothing about how the growth of charters in particular districts is likely to affect the ability of those districts to provide quality schooling to the children in the traditional public schools. That issue is currently an urgent concern in the Durham County, for example, where the rapid growth of charters has not only increased racial segregation, but also has imposed significant financial burdens on the school district. One recent study found that the net cost to the Durham Public Schools could be as high as $2,000 per student enrolled in a charter school, although the precise amount differs based on the assumptions (Troutman, 2014). Major contributors to this burden are the fact that the charter schools serve far lower proportions of expensive-to-educate children than the traditional public schools and that the district cannot reduce its spending in line with the loss of students because of its fixed costs.

In ongoing research we plan to investigate further the evolving financial and other implications of charter schools on districts’ traditional public schools.

In another line of inquiry we are exploring the extent to which the goals of charter schools have been changing over time. One approach is to compare the goals stated in the charter school applications of charters approved at different points over time to examine changes in the types of students they intend to serve (e.g. low income and minority, disabled students, or all students), their subject focus (e.g. STEM, general purpose, or other) and their pedagogical approach (e.g. normal grade format, mixed grades, or Montessori). Another approach is to examine the backgrounds of charter school board members over time to tease out the extent to which charters are becoming more of a business proposition and less of an innovative way of providing education.

In this case, however, state policy makers have both the power and the responsibility to influence that evolution.

As would be predicted by the standard market model of competition, the charter school sector in North Carolina will undoubtedly continue to evolve. In this case, however, state policy makers have both the power and the responsibility to influence that evolution. In particular, they have the authority to limit the number of entrants or to alter the authorization and review processes. The question is whether they will use that authority to assure that the sector serves the public interest and not just the private interests of those who send their children to charter schools.

References for excerpt:

Troutman, Elizabeth. 2014. Refocusing Charter School Policy on Disadvantaged Students. Master Thesis, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University.