On-time transition to college means that high school graduates enroll in a postsecondary institution in the fall of their graduating year. This immediate college-going rate is an indicator of the share of graduates on a traditional postsecondary path. Although many individuals delay entry into postsecondary education, immediate college enrollment is the easiest point at which institutions and policy makers can intervene.

How is North Carolina performing?

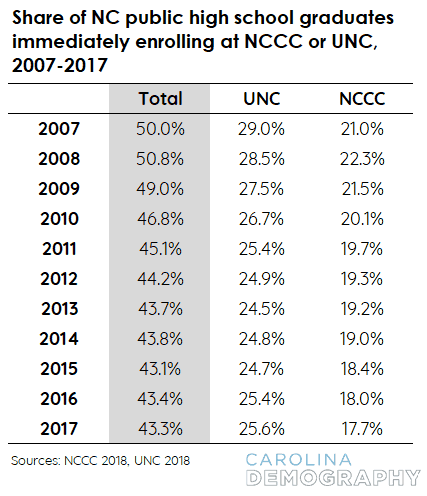

Forty-three percent of graduates from NC public high schools in 2016-17 were enrolled at either NCCC or UNC in fall 2017, as shown in Table 6. This represents a decline of more than seven percentage points from peak college-going rates in 2008 (50.8%). Both NCCC and UNC experienced declines in immediate enrollment rates over this time:

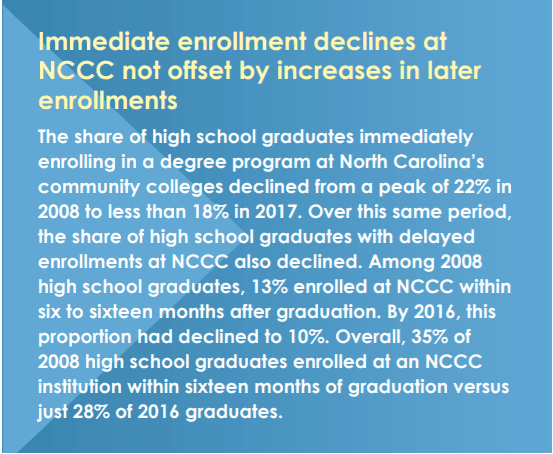

- Immediate enrollment rates for NCCC peaked in 2008 at 22.3%. This rate has declined in every subsequent year, reaching 17.7% in 2017.

- Immediate enrollment rates peaked for UNC in 2007 at 29.0%. This rate declined to a low of 24.5% in 2013. Though immediate enrollment rates for UNC increased to 25.6% in 2017, they remain more than three percentage points below their 2007 peak.

These trends suggest the impact of broader economic conditions on college-going rates. During economic contractions, such as the Great Recession, individuals may be more likely to enroll in postsecondary programs because of a combination of fewer opportunities and increased competition for a limited pool of jobs. As the economy improves, they may choose to enter immediate employment rather than enroll in college.

Although the economy may explain some of these declines, the immediate enrollment rates for UNC declined during the height of the recession (2007-09), and NCCC immediate enrollments have steadily declined since 2008. What else could be influencing these trends? In addition to the growing opportunities for employment after the recession, three other factors may be influencing the immediate enrollment rate trends observed at both NCCC and UNC:

- Rising high school graduation rates

- Changing demographics

- Rising private and out-of-state enrollments as the economy improves

Despite steady increases in the number of students graduating from high school, the number immediately enrolling in college has only recently increased

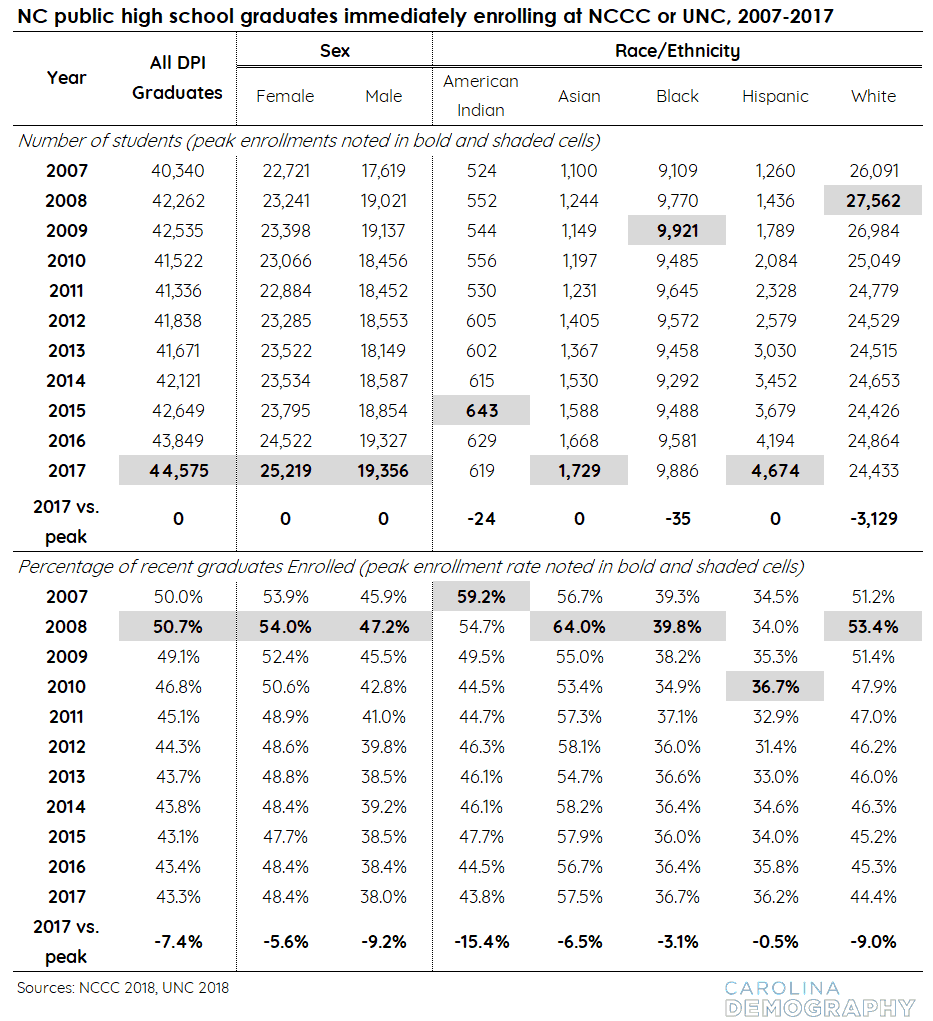

NC students are completing high school at a higher rate than ever before, but this has not translated into large increases in immediate college enrollments. Until very recently, the declines in the immediate college-going rate were accompanied by a decline in the absolute number of high school graduates enrolling at NCCC or UNC, as shown in Table 7.

Following their 2009 peak of 42,535 students, the number of immediate fall enrollments at NCCC or UNC declined to a low of 41,336 in 2011. Enrollments slowly began to rise but did not surpass their 2009 peak until 2015 (42,649), despite the total number of high school graduates increasing by 12,130 over this time. This larger pool of graduates may include more students who lack interest in postsecondary education or who have social or demographic characteristics associated with the reduced likelihood of immediate college enrollment (e.g., first-generation students).

Since 2015, the number of total enrollments at NCCC or UNC has steadily increased. This mainly reflects a larger number of high school graduates, not significant changes in the college-going rate.

Immediate college-going rates declined for all demographic groups

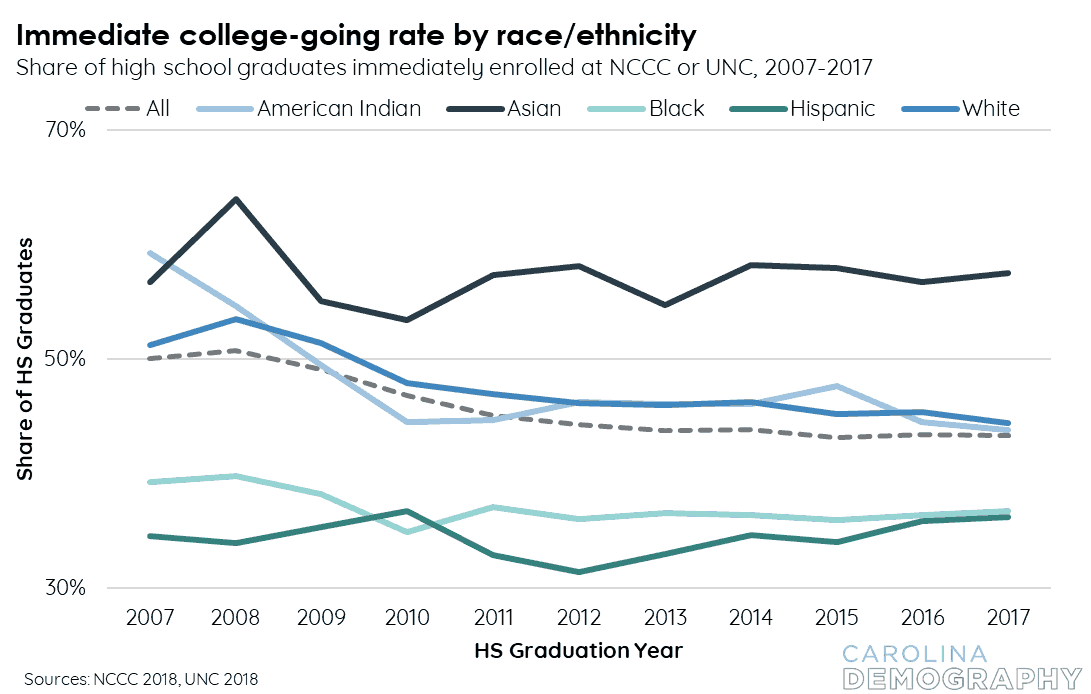

A second potential explanation is the state’s changing demographics. As our population grows increasingly diverse, persistent group differences in the likelihood of transitioning to college may begin to influence the statewide trend unless these gaps begin to narrow. However, Table 7 shows that the college-going rate has declined from its peak for all demographic subgroups. In 2007, more than half of female (53.9%), American Indian (59.2%), Asian (56.7%), and White (51.2%) graduates immediately transitioned to college. By 2017, Asian graduates were the only group where more than half of graduates (57.5%) made an on-time transition to NCCC or UNC:

- Immediate enrollments of female graduates peaked in 2008 at 54.0% and declined by 5.6 percentage points to 48.4% in 2017.

- Immediate enrollments of male graduates were 47.2% in 2008 and declined to 38.0% in 2017, a decrease of 9.2 percentage points.

- Immediate enrollments of American Indian graduates peaked at 59.2% in 2007 and declined by 15.4 percentage points to 43.8% in 2017. This was the largest decrease of any group.

- Immediate enrollments of Asian graduates decreased from 64.0% in 2008 to 57.5% in 2015, a decrease of 6.5 percentage points.

- Immediate enrollments of Black graduates peaked at 39.8% in 2008 and declined by 3.1 percentage points to 36.7% in 2017.

- Immediate enrollments of Hispanic graduates decreased from 36.7% in 2010 to 36.2% in 2017, a decrease of 0.5 percentage points. While this was the smallest decrease of any group, Hispanic graduates were the least likely to immediately transition to college in 2007 and remained the least likely to immediately transition in 2017, though their immediate enrollment rates have been steadily increasing since their lowest point in 2012.

- Immediate enrollments of White graduates peaked at 53.4% in 2008 and declined by 9.0 percentage points to 44.4% in 2017.

- In addition to these changes in the percentage of students enrolled, there were numerically fewer American Indian (-24), Black (-35), and White (-3,129) graduates who immediately transitioned to college in 2017 compared with their peak year of numeric enrollments.

Rebounding private and out-of-state enrollments do not fully account for the decline in immediate college-going rates

The final potential explanation for the observed decline in the in-state public college-going rate is that graduates who enrolled in postsecondary institutions were more likely to stay in state and attend public institutions during the Great Recession. As the economy improved, students may have returned to in-state private institutions and out-of-state colleges and universities. The full significance of this for immediate NCCC and UNC enrollment cannot be tested with the existing data set. Examining the limited data available on immediate college enrollments suggests that rebounding enrollments at out-of-state and private institutions may have played a role in the declining immediate enrollment rates observed at NCCC and UNC but cannot fully account for observed declines.

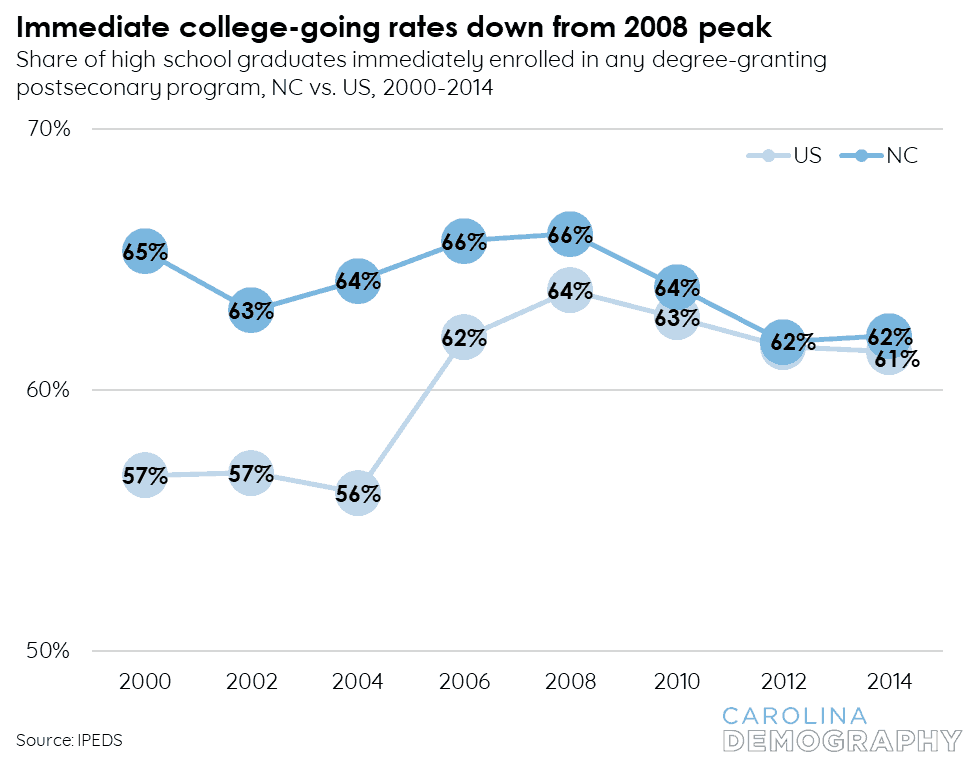

Figure 34 displays the share of high school graduates who immediately enrolled as degree- or non-degree-credential-seeking undergraduates at degree-granting postsecondary institutions for both the US and North Carolina from 2000 to 2014.1 Sixty-two percent of the state’s 2013-14 high school graduates immediately transitioned to college in fall 2014, slightly higher than the national rate of 61%. Immediate college-going rates declined from their 2008 peak nationally and in North Carolina, but declines were more pronounced in North Carolina. In 2008, the nationwide immediate college-going rate was 64%, nearly three percentage points higher than the 2014 rate. North Carolina’s immediate college-going rate peaked even higher: 66% of high school graduates enrolled in postsecondary programs in 2008, four percentage points higher than in 2014.

Over this same period (2008 vs. 2014), the immediate enrollment rates for NC public high school graduates at NCCC and UNC colleges declined by seven percentage points, nearly twice the decline in the state’s immediate college-going rate shown in the national data.2 This suggests that some of the decline in immediate enrollments at the state’s public institutions may be due to rising enrollments at private and out-of-state institutions. However, the greater decline in North Carolina’s immediate college-going rate compared with the national decline highlights potential challenges in moving toward future attainment goals.

Demographic differences

Whether we examine the peak enrollment year of 2007, the most recent data from 2017, or any year between, there are persistent differences across demographic subgroups in immediate college-going rates.

Black and Hispanic graduates are consistently less likely to immediately transition to college

Between 2007 and 2017, Asian graduates were consistently the most likely to immediately enroll at NCCC or UNC, as shown in Figure 35. White and American Indian graduates enrolled at rates near the state average, while Black and Hispanic graduates were the least likely to enroll at NCCC or UNC in the fall semester after their high school graduation.

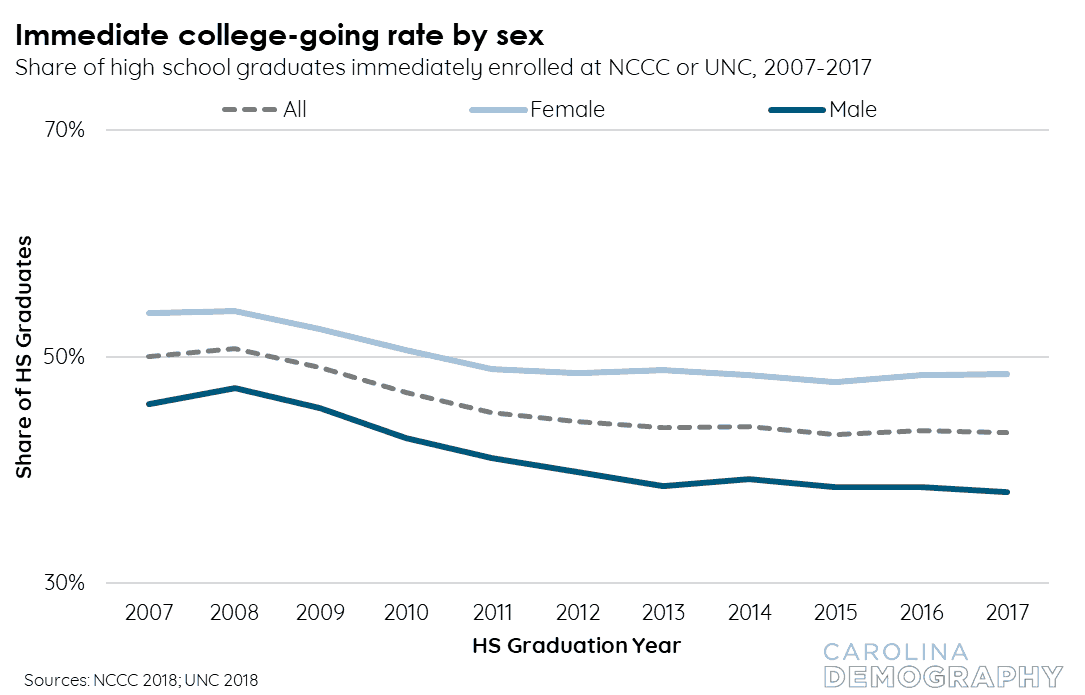

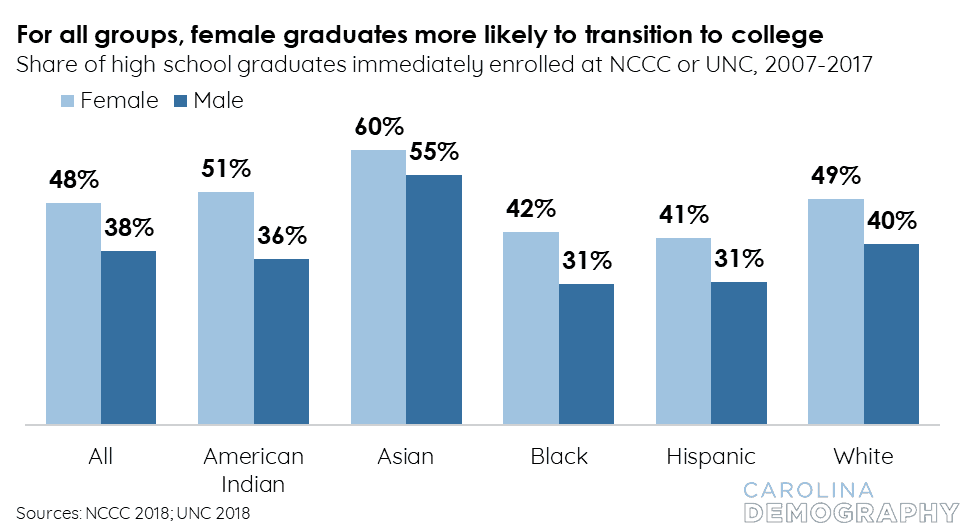

The gap between male and female graduates’ on-time enrollment rates is large and growing

For all years, there was a large gap in immediate enrollment rates between male and female graduates (Figure 36). Fifty-four percent of female high school graduates immediately transitioned to NCCC or UNC in 2007 compared with 46% of male high school graduates, a gap of eight percentage points. This gap briefly narrowed to seven percentage points in 2008 and has since widened. In 2017, the immediate college-going rate for female graduates was ten percentage points higher than the rate for male graduates: 48% versus 38%.

Female graduates were more likely to immediately enroll in college than male graduates across all demographic subgroups in 2017 (Figure 37). The smallest gap between male and female enrollment rates in 2017 was among Asian graduates: 60% of female graduates immediately transitioned to college compared with 55% of male graduates, a gap of five percentage points. This college-going rate gap was larger among other subgroups:

- 9 percentage points among White graduates (49% vs. 40%)

- 10 percentage points among Hispanic graduates (41% vs. 31%)

- 11 percentage points among Black graduates (42% vs. 31%)

- 15 percentage points among American Indian graduates (51% vs. 36%), the largest difference among the subgroups

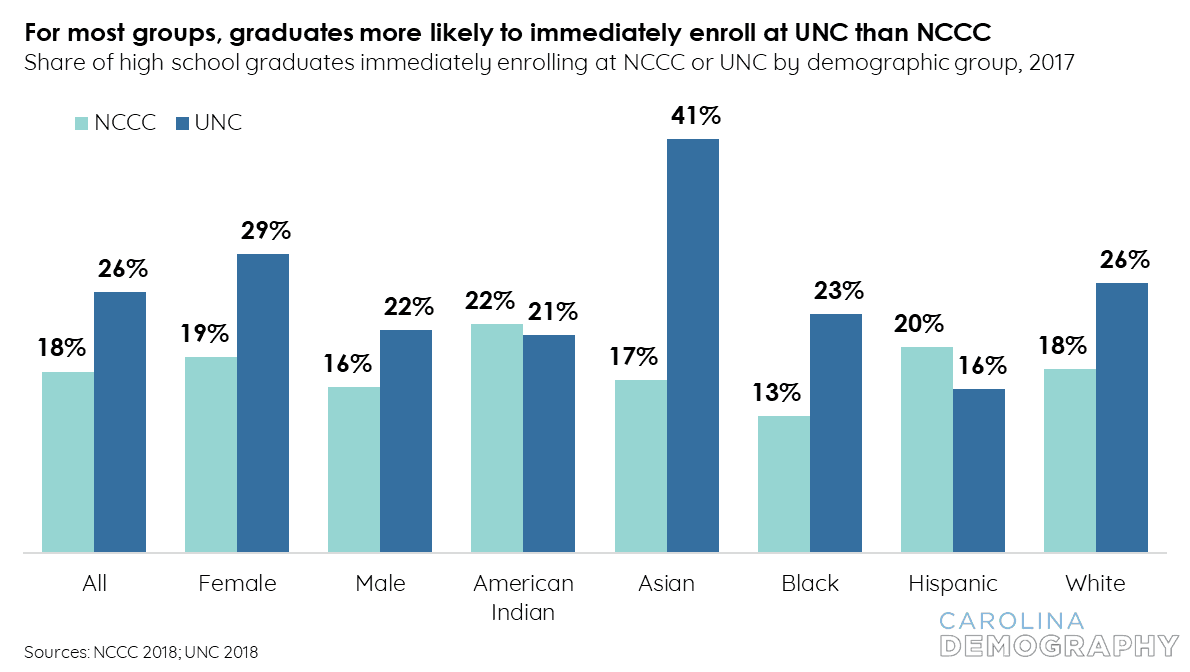

Students who immediately enroll are more likely to enroll at UNC than NCCC

NC public high school graduates who immediately enrolled in college were more likely to enroll at one of the sixteen UNC institutions than at one of the state’s fifty-eight community colleges. Twenty-six percent of all recent graduates immediately transitioned to UNC in 2017, while 18% immediately transitioned to NCCC. This pattern is not the same for all subgroups, however, as shown in Figure 38.

Asian graduates were much more likely to enroll at UNC than NCCC: 41% of all Asian graduates enrolled at UNC in 2017 versus 17% at NCCC. In contrast, American Indian and Hispanic graduates were more likely to enroll at NCCC than UNC:

- 22% of all American Indian graduates immediately enrolled at NCCC in 2017 versus 21% at UNC

- 20% of all Hispanic graduates immediately enrolled at NCCC versus 16% at UNC

Pipeline takeaway

Transition to college is the largest loss point in the postsecondary pipeline, and the size of this loss is growing

In 2017, less than half of NC public high school graduates, 43.3%, immediately enrolled at either NCCC or UNC in the fall. This was 7.4 percentage points less than the immediate college-going rate of 50.7% in 2008. Both NCCC and UNC experienced declines in immediate enrollment rates over this time:

- Immediate enrollment rates for NCCC peaked in 2008 at 22.3%. This rate declined by more than four percentage points to 17.7% in 2017.

- Immediate enrollment rates peaked for UNC in 2007 at 29.0%. This rate declined to 24.5% in 2013 and

rebounded slightly to 25.6% in 2017, three percentage points below the 2007 peak.

More high school graduations have not translated directly into more college enrollments

For every year between 2010 and 2014, the number of students immediately enrolling at either NCCC or UNC fell below the 2009 peak of 42,535, despite steady annual increases in the number of students graduating from high school. Between 2009 and 2017

- the number of graduates from NC public schools grew from 86,716 to 102,945, an increase of 16,229 (19%), and

- the number of graduates immediately enrolling at UNC or NCCC grew from 42,535 to 44,575, an increase of 2,040 (5%).

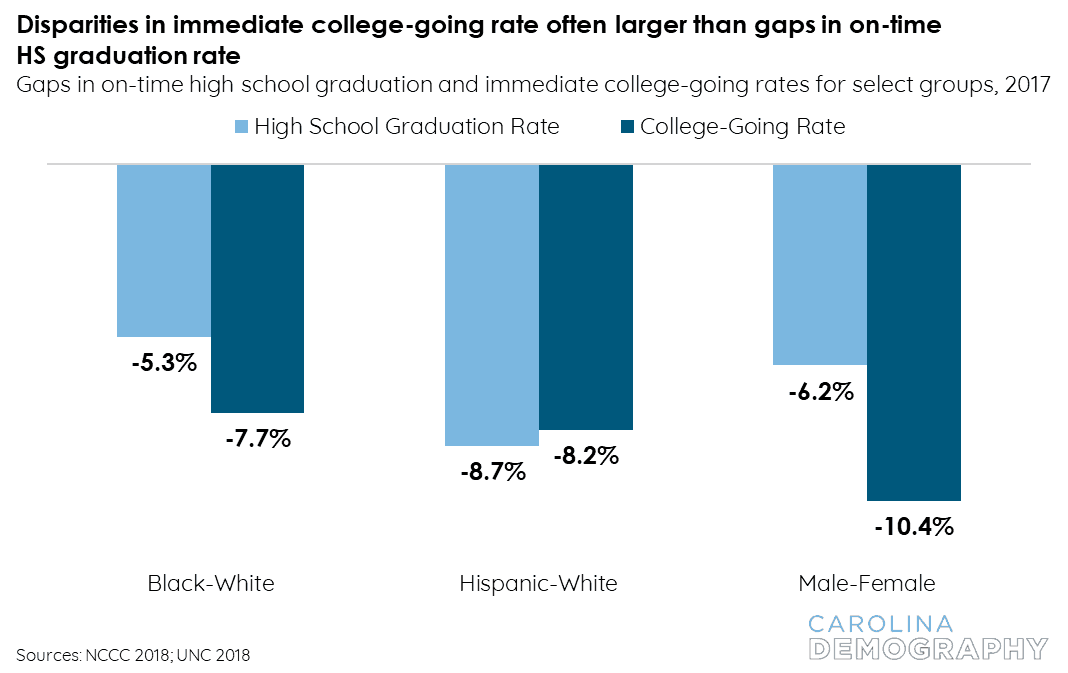

Large disparities in the on-time transition to college across demographic groups further highlight the need for increased focus on transition to postsecondary education

For key groups, gaps in the immediate college-going rate at NCCC or UNC were as large or larger than gaps in on-time high school graduation rates (Figure 39). In 2017

- the Black-White gap was 5.3 percentage points for high school graduation but 7.7 for immediate college-going;

- the Hispanic-White gap was 8.7 percentage points for high school graduation and 8.2 for immediate college-going; and

- the male-female gap was 6.2 percentage points for high school graduation but 10.4 for immediate college-going.

Successfully increasing the enrollment of our state’s Hispanic and Black students and male students will be a critical step toward successfully reaching any statewide attainment goal.

Editor’s note: The Belk Endowment supports the work of EducationNC. To read the full report and view the data, visit ncedpipeline.org.