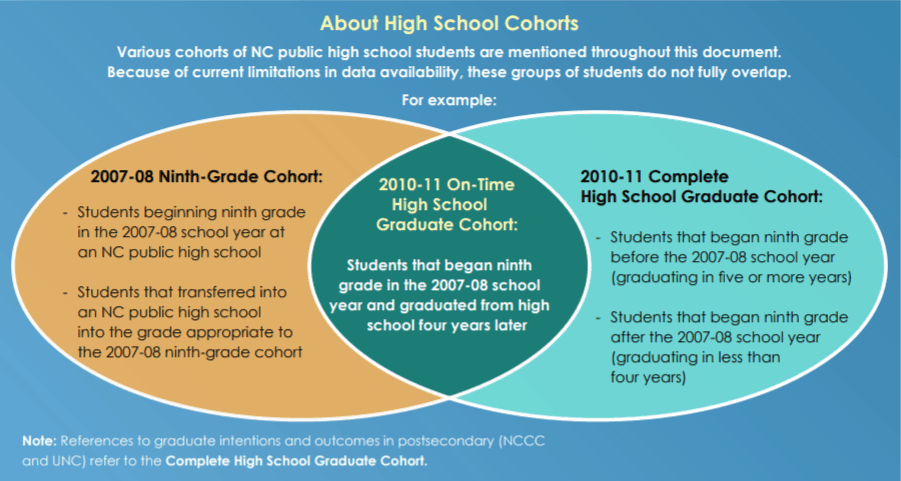

The most recent complete pipeline data are for the cohort of NC public school students who entered ninth grade in the 2007-08 school year. They may be referred to as the “2008 ninth graders” or the “2008 ninth-grade cohort” in the remainder of this section.

There were 110,400 students enrolled in ninth grade at a public school in North Carolina in 2007-08. Ten years later, just 17,200 (16%) of these students had made an on-time transition to NCCC or UNC and received a degree from that system. What happened to the other 93,200 students?

- Twenty-two percent, or 24,400, dropped out of high school or took longer than four years to graduate.

- Forty-three percent, or 47,200, graduated from high school on time but did not enroll at NCCC or UNC in the fall. This number includes students who initially enrolled in a private or out-of-state institution, students who delayed enrollment, and students who never enrolled in college.

- Twenty percent, or 21,600, enrolled at NCCC or UNC in the fall but did not complete a degree within 150% of normal time (three or six years, respectively). This number includes students who transferred to another institution and students who took longer than three or six years to complete a degree:

- Ten percent did not return for their sophomore year.

- Four percent of all entering students at NCCC or UNC did not return for spring semester.

- Six percent completed one year but did not return for their second year.

- Ten percent returned for a second year at NCCC or UNC but did not complete a degree in a

timely fashion.

- Ten percent did not return for their sophomore year.

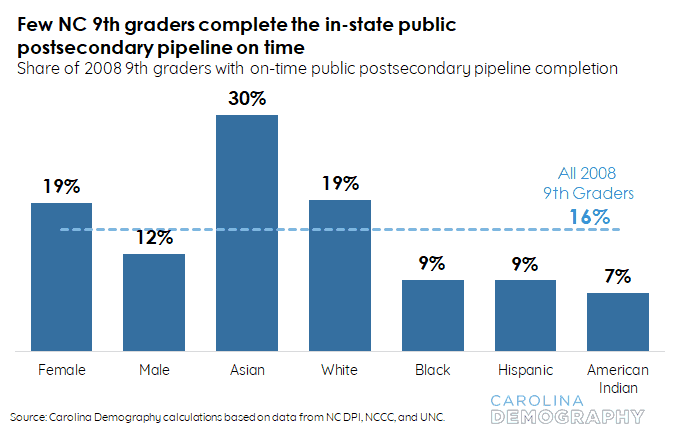

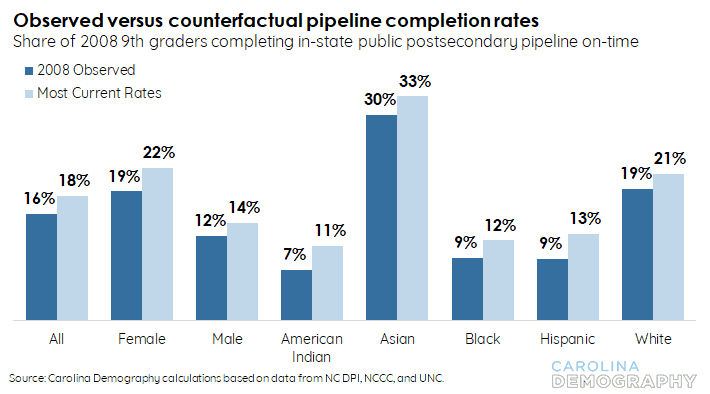

Statewide, 16% of North Carolina’s 2008 ninth-grade cohort successfully completed the in-state, public postsecondary pipeline at NCCC or UNC by 2017 (Figure 7). The pipeline completion rate for female students (19%) exceeded their male counterparts (12%) by seven percentage points.

Among the state’s racial/ethnic subgroups, Asian students were the most likely to complete the public postsecondary pipeline on time. Thirty percent of the state’s Asian ninth graders in 2007-08 had received a degree from NCCC or UNC by 2017. White student completion rates were also above the state average (19%). In contrast, the state’s Black (9%), Hispanic (9%), and American Indian (7%) students had pipeline completion rates far below the state average.

Pipeline completion rates for ninth graders by sex and race in combination cannot be calculated due to a lack of detailed data on high school graduation rates.

Where are the leaks?

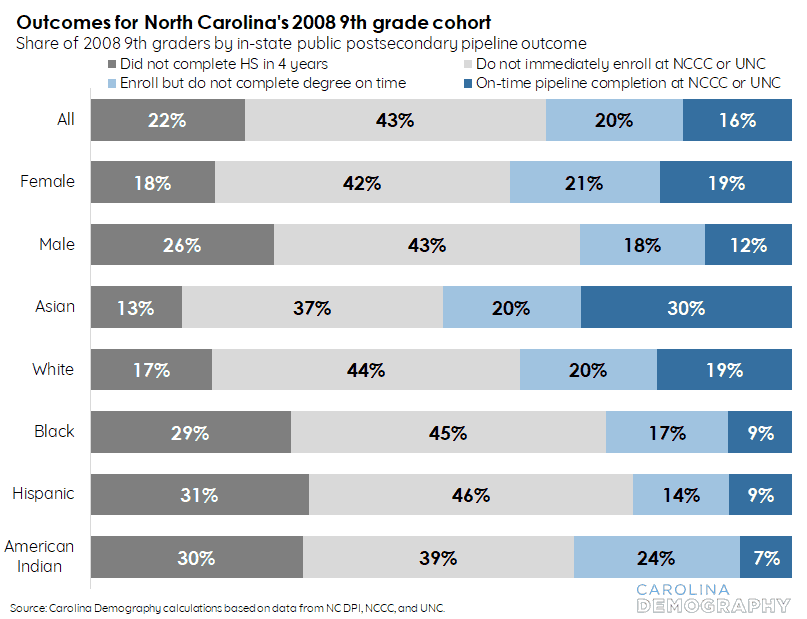

The specific magnitude of these leaks varied across demographic subgroups. Figure 8 highlights both the percentage of ninth graders who successfully completed the in-state public postsecondary pipeline (in dark blue) and the transition points where those who did not complete were lost (gray and light blue bars).

For all demographic groups in the 2008 cohort, the transition between high school and postsecondary education was the largest loss point in the postsecondary pipeline. This is also the hardest loss point to understand with existing quantitative data. Some of this is true loss from the pipeline. Other students may be continuing their education at an out-of-state or private institution; they are currently “lost” due to inadequate data to fully track all students through the postsecondary pipeline.

The second largest loss point overall was timely high school completion. Twenty-two percent of the 2008 ninth-grade cohort did not graduate high school within four years. This rate was much higher for Male students (26%), Black students (29%), American Indian students (30%), and Hispanic students (31%). Dropping out or delaying high school completion was a smaller loss point for female students (18%), White students (17%), and Asian (13%) students; not completing postsecondary education on time was a greater loss point for these groups.

Finally, one in five of the 2008 cohort (20%) enters an NC public postsecondary institution on time but did not complete a degree within three or six years. Less than half of individuals who enrolled at NCCC or UNC in the fall successfully completed a degree from that system within three or six years, respectively. Some of these students may transfer and complete at other institutions: 16% of UNC’s first-time, full-time fall enrollments in 2010 transferred to another institution, for example, as did 21% of NCCC 2013 fall enrollments, although the outcomes for an even greater share were unknown (18% for UNC and 46% for NCCC).1

Though failing to complete postsecondary education on time is a relatively smaller loss point for Black (14%) and Hispanic (17%) students, this primarily reflects heavier losses earlier in the pipeline, rather than better outcomes within postsecondary. Among the 2008 ninth-grade cohort, just 35% of Black students and 40% of Hispanic students with on-time enrollment at NCCC or UNC received a degree within 150% of normal time.

How have the leaks changed over time?

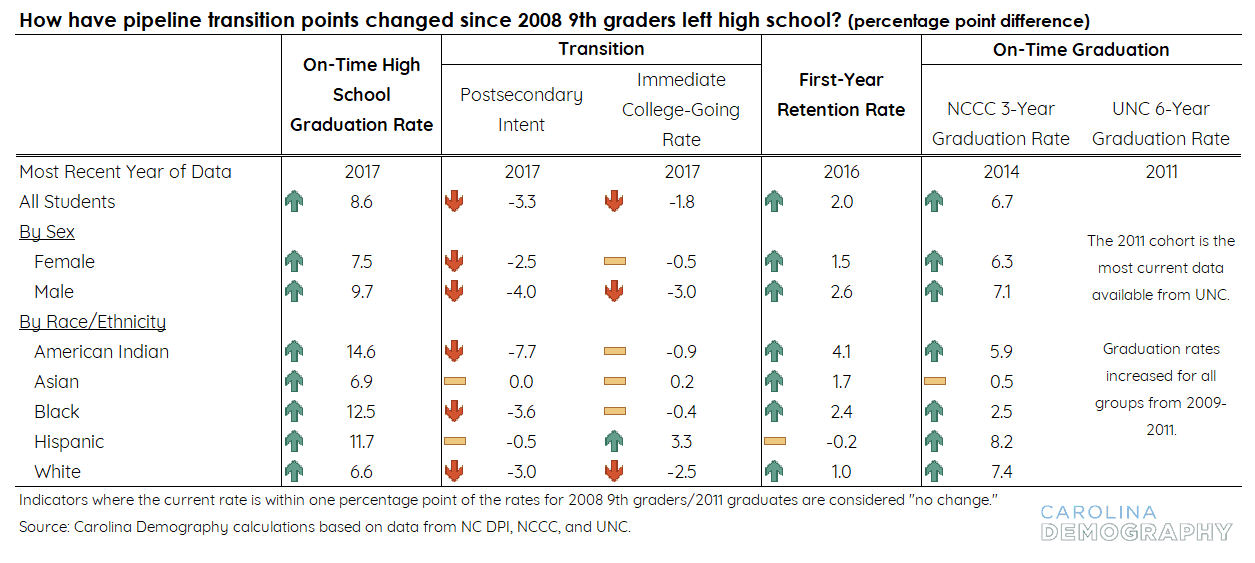

The most recent full pipeline data is for 2007-08 ninth graders who graduated from high school in 2011. Since 2008, many of the transition probabilities have changed. Table 1 details how the key pipeline transition points have changed across demographic groups. One of the largest improvements in education over the past decade, for example, is the steady rise in four year high school graduation rates, with the largest gains among our state’s Black, American Indian, and Hispanic students.

While on-time high school graduation rates have improved, recent graduates are less likely than those who graduated in 2011 to report postsecondary intentions and are less likely to immediately transition to college. However, once enrolled at NCCC or UNC, first-year students are more likely to return to that system for a second year compared with 2011 high school graduates. Those students attending community colleges have an increased probability of completing a degree or credential within three years.

In combination, how do these changes in transition probabilities affect the overall likelihood of successful completion of North Carolina’s public postsecondary pipeline?

What if the 2008 ninth-grade cohort experienced the most current transition probabilities?

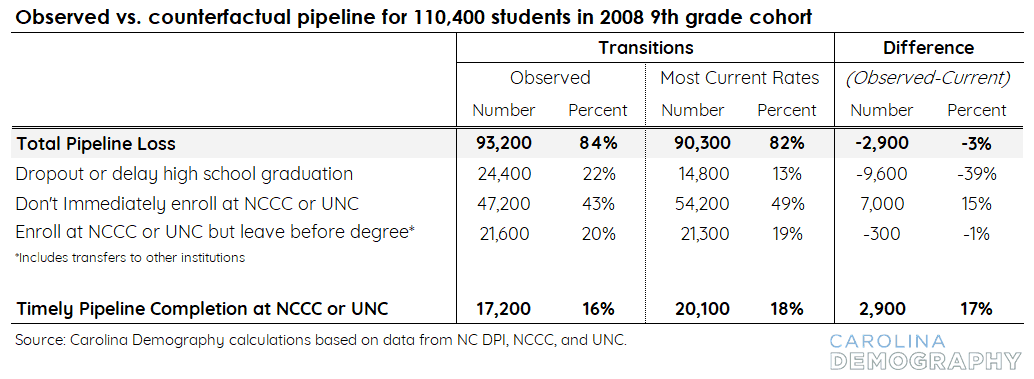

There were 110,400 students enrolled in ninth grade at a public school in North Carolina in 2007-08. What are the outcomes if we expose them to the most recently available transition rates? Ten years later, we would have expected the following to be true, as detailed in Table 2:

Thirteen percent, or 14,800, would have dropped out of high school or delayed graduation. This represents 39% fewer dropouts than the number of students who did drop out of this cohort (24,400), underscoring the major improvements in high school completion in the state. Graduation rates were already improving by the time the 2007-08 ninth graders entered high school and have continued to improve since they left. If the 2007-08 ninth graders had been exposed to current four-year graduation rates, 9,600 additional students would have completed high school on time. This represents an increase of 11% in on-time graduates statewide, and even larger increases would be seen for minority groups. Under current rates, the 2008 entering ninth-grade class would have seen the following increases:

- 21%, or 238, more American Indian high school graduates

- 17%, or 1,081, more Hispanic high school graduates

- 17%, or 4,100, more Black high school graduates

Combined, more than half of the increase in new high school graduates (57%) would be from the increase in American Indian, Black, and Hispanic on-time graduates.

Forty-nine percent, or 54,200, would have graduated from high school on time but would not immediately enroll at NCCC or UNC in the fall. This is 7,000 more students who would be lost between high school graduation and fall enrollment than were previously lost (47,200). Under the most recent rates, 15% more students are lost between graduation and college entry.2

Although the larger number of high school graduates would yield an additional 2,600 immediate enrollments at NCCC or UNC, many of the gains in high school graduates are subsequently lost in increased failure to transition on time. Some of this loss reflects the basic fact that when graduation rates improve, the students who benefit most from the improved rates may be more likely to lack interest in attending college. An evaluation of the high school graduate intention data from the NC Department of Public Instruction (DPI) between 2006 and 2017, for example, shows a two percentage point decrease in the intention to enroll in any postsecondary program among all NC high school graduates over this period.

Because this graduation-to-postsecondary enrollment transition point has so many potential reasons for loss, however, we cannot fully understand how changes in graduate loss at this point are improving, worsening, or staying the same until our data and evaluations improve.

Nineteen percent, or 21,300, would enroll on time at NCCC or UNC but leave prior to timely degree completion (three or six years, respectively). This is a decrease of 300 ninth graders, or 1%, from the observed number of 21,600. Although the likelihood of transitioning to postsecondary education decreased, the share of students successfully completing their degrees once enrolled did increase.

Eighteen percent, or 20,100, would have graduated from high school on time, transitioned on time to NCCC or UNC, and received a degree on time. This represents an additional 2,900 NC public high school students who would have transitioned on time and received a degree on time—an increase of 17%. On this indicator, too, the largest improvements in recent years were observed for our state’s minority students.

If the 2008 ninth-grade cohort had been exposed to current conditions, fifty-seven additional American Indian ninth graders would have completed high school on time, immediately transitioned to NCCC or UNC, and received a degree on time, an increase of 47%. This was the largest percentage increase of any demographic group, followed by Hispanic (+339 or 41%) and Black (+843 or 28%) students.

Despite these improvements in key transition areas, the overall pipeline completion rates remain low: 18% (if exposed to current rates) versus 16% (observed), as shown in Figure 9. While the specific areas of loss changed, exposing the 2007-08 ninth-grade cohort to current transition probabilities would still yield 90,300 ninth graders lost at some point in the pipeline. Moreover, large disparities persist in the likelihood of timely pipeline completion at NCCC or UNC. Though American Indian, Black, and Hispanic students would see significant increases in the likelihood of pipeline completion under current rates, their improved completion rates would still lag the state average by five to seven percentage points.

How many future students might be lost?

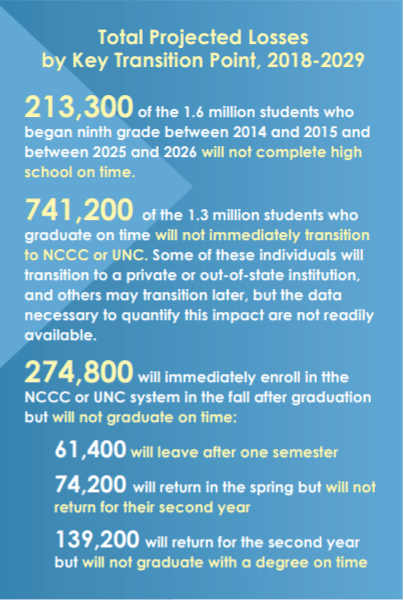

Between the 2014-15 and 2025-26 school years, nearly 1.6 million students will enter ninth grade in North Carolina’s public high school system (see Appendix D for projection methodology details).3 These ninth graders will graduate between 2018 and 2029 if they complete high school in four years. Under current high school graduation rates, at least 213,300 of these students will drop out of high school or take longer than four years to graduate.

In total, North Carolina’s public K-12 school system is projected to produce 1.3 million high school graduates between 2018 and 2029. Under current transition rates,

- 246,900 graduates will not immediately enroll in postsecondary programs due to lack of interest;

- 494,300 graduates with intention to enroll in postsecondary programs will not immediately enroll at NCCC or UNC;

- 274,800 graduates will immediately enroll at NCCC or UNC but will not graduate on time:

- 61,400 will leave after one semester

- 74,200 will return in the spring but will not return for their second year

- 139,200 will return for a second year but will not graduate on time; and

- 261,200 graduates will immediately enroll at NCCC or UNC and complete a degree on time (three or six years, respectively)

By 2030, North Carolina is projected to need just over 250,000 more adults with a postsecondary degree or nondegree credential to meet 60% postsecondary attainment. Over this time, more than 200,000 ninth graders will drop out of high school or fail to complete on time. Hundreds of thousands more students are projected to graduate from high school but never transition to college or are projected to begin college but not complete. Improving outcomes for these students would increase their long-term economic potential and raise attainment levels statewide.

Educational attainment is part of a decades-long process and is the sum of educational experiences and exposures that begin at birth and continue well into adulthood. Overall pipeline completion is the cumulative result of success across multiple transition points. Each transition point offers an opportunity for intervention to improve educational outcomes for individuals and North Carolina as a whole. In the remainder of this report, we examine in detail how these key transition points have changed for our state.