When my father arrived home from work, he would turn on ESPN. When my mother came downstairs, she would change the channel to E! News. The History Channel was their compromise, which meant I ate my Kid Cuisine dinners fascinated with the political struggles of World War II, fierce debates over the Constitution, and the triumphs and tragedies that define our nation.

As a result, I liked history as much as any other kid, but it wasn’t until Mr. Bagley’s 8th grade American history class that I began to understand the beauty and necessity of learning about our past. Mr. Bagley was the classic American teacher. He was an older and wiser man with a warm smile, ready to give encouragement. He would tell us stories about our small town in New Jersey and could seamlessly weave his personal narrative into the story of our nation’s history.

Mr. Bagley studied art in college, so every unit began with beautiful cartoon images drawn in chalk on the board. He did not teach history as concepts and dates to be sketched out on worksheets. In his class, history was a series of battles for humanity and morality in an ever evolving ebb and flow of progress and tradition. Most importantly, Mr. Bagley showed me women from the past and present whose work impacted and improved American society. He taught me that I could be just like them.

In his 8th grade classroom, I decided I was going to become the President of the United States, both because I fell in love with his stories about our past presidents and because he made me believe that I could.

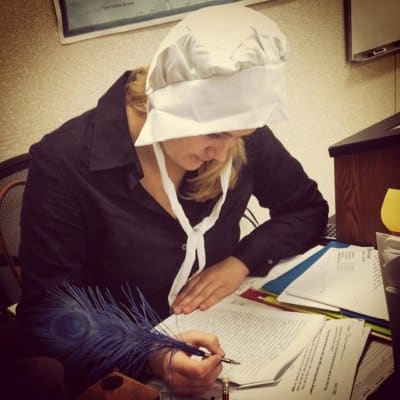

When I became an American history teacher in Warren County, North Carolina, I tried to emulate Mr. Bagley. He dressed up as a Civil War soldier and transformed our classroom into a Union camp; I transformed my classroom into a World War I trench, and led other lessons dressed as Rosie the Riveter or a Puritan colonist. He taught me that history was the story of the human experience; I taught my students the same, showing them the meaning of friendship with Adams and Jefferson, or the depths of loss with Teddy Roosevelt’s last journal entry.

Before I became a teacher, Mr. Bagley was my ideal. When I served in the classroom, I developed another favorite teacher: my former coworker, Ms. Seitz. Lovingly known as Mama Seitz, she teaches English with high expectations, culturally responsive lessons, and above all, love. She taught me how to be a teacher.

When a student collapsed in my classroom crying, another stood up and calmly said, “I’ll go get Ms. Seitz.” When I grew frustrated that a student was not turning in papers or participating, she would inform me that he was barely literate, and the only way he would write papers for her is if he orated them. When a normally chipper student could no longer lift his head up from his desk, Ms. Seitz would fill me in on what was going on at home. My greatest accomplishments as a teacher are tied to her influence or advice.

On more than one occasion, she taught a high school student how to read.

Her work continues. She refuses to let anyone slip through the cracks, and instead nurtures and encourages her students to persevere and have grit. She creates leadership opportunities for the students, plans field trips, and establishes a culture of safety and love in her classroom and school. Her students live in an impoverished county and encounter the trauma that accompanies poverty with unfortunate regularity. Ms. Seitz’s classroom is a refuge where students go to feel valued, listened to, and loved. By creating an environment that values their humanity, her students’ academic potential becomes limitless.

Years from now, students will remember Ms. Seitz for the same reasons that I remember Mr. Bagley; she inspired them, she supported them and their dreams, and she taught with love. And while she did all this for her students, she somehow managed to do the same for me.

Recommended reading