Why do some students eat lunch from the school cafeteria while others bring their lunches from home? Why do school cafeterias offer limited options? The reasons may relate to cost, preference, convenience, selection or a number of other factors. A recent gathering of students, parents, school staff, and policymakers examined the subject of school meals.

Reach NC Voices, a project of EducationNC, and the World Policy Food Center at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University hosted the State of the Plate Food Workshop on Monday. Participants from Durham and Edgecombe counties discussed the barriers each group faces in providing healthy and delicious school food.

Jim Keaten, child nutrition director of Durham Public Schools, shared memories from his childhood of being a “free and reduced lunch kid.”

“It was very disheartening to always be associated as different. The first thing I worked on [as Child Nutrition Director] was universal free breakfast,” he said. “We don’t care about your status – you come to the cafeteria and get a free breakfast.”

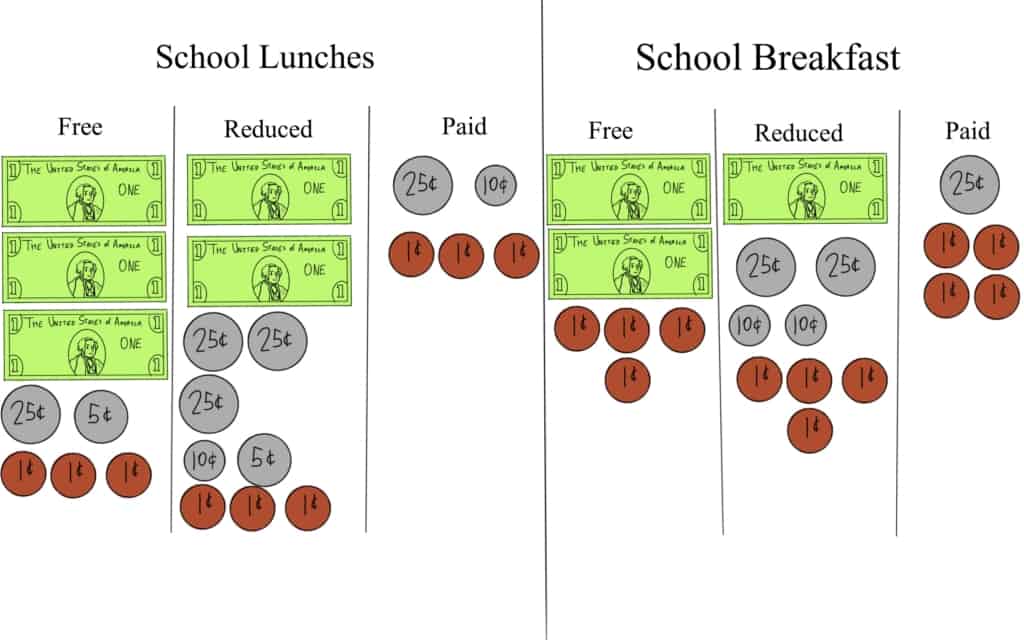

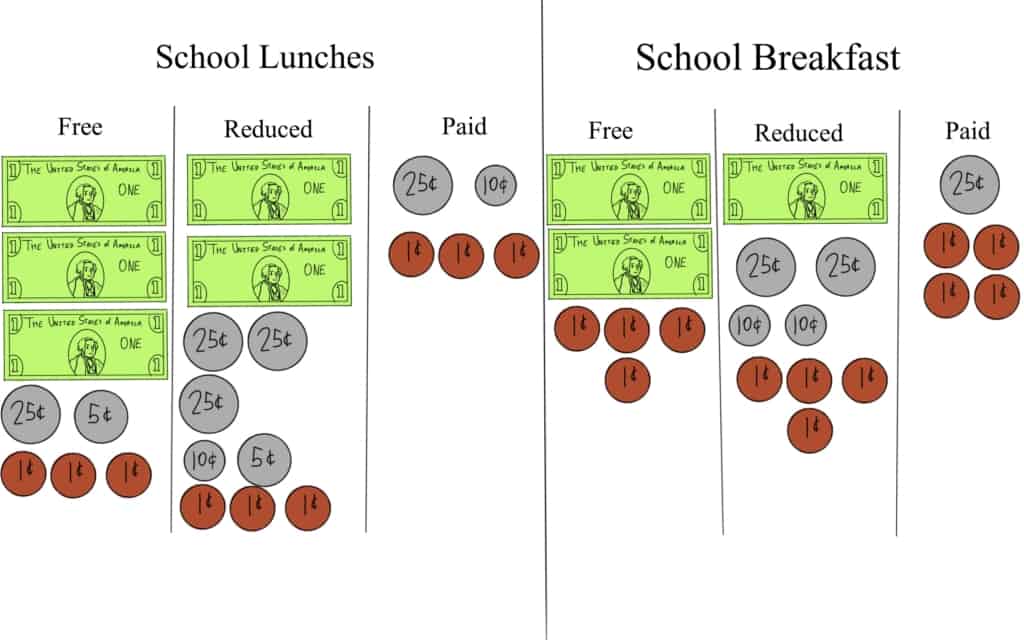

Keaten explained that Child Nutrition Services operates on a budget that is separate from the school and must operate as revenue neutral. The state provides a small amount of additional funding beyond the required federal match, and only for reduced-price breakfasts.

“Child nutrition does not receive any funding from anyone except for the parents paying for the meals and federal government reimbursement,” Keaten said. “When [the government] says teachers and all state workers are getting raises, that means my staff is getting a raise too. However, that money has to come out of the money I raise through selling meals. The state mandates that I have to give a raise, but doesn’t give me any money for that.”

Keaten also shared the struggles the department faces with restrictions from the federal, state, and local governments. For example, a Durham County regulation prevents students from self-serving, which means that Durham County Schools can not have a salad bar, even though there is high demand for it.

Charter schools also face challenges in school nutrition. Stephanie Terry, owner of Sweeties Southern and Vegan Catering, prepared meals for a Durham Charter school. Their lunch program won grand prize in a national award that “recognizes food service teams doing exceptional work to improve the healthfulness of school lunches.”

But financial and legislative barriers made it impossible for her company to continue the partnership.

“There was zero profit,” Terry said. “There was no way we could make the quality of lunch of our menu and meet all of the very strict legislation and policy around procurement. We would find the same bun made by a local bakery that met all of the requirements, but because it was not the brand specified by the contract, we would potentially be considered out of compliance.”

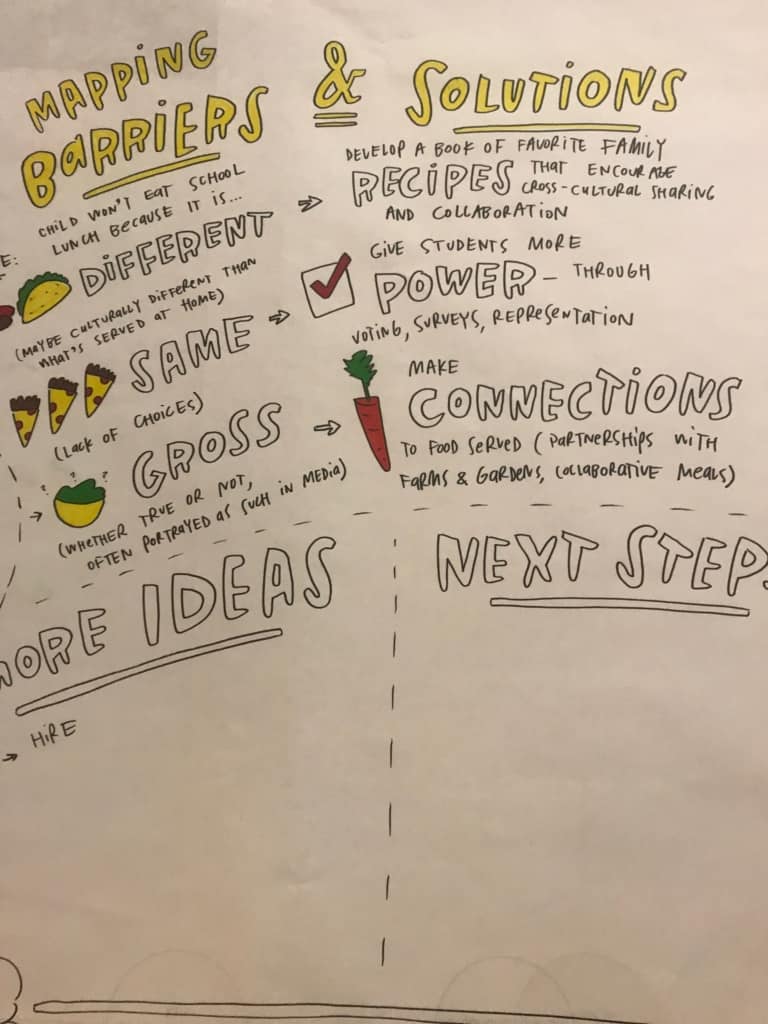

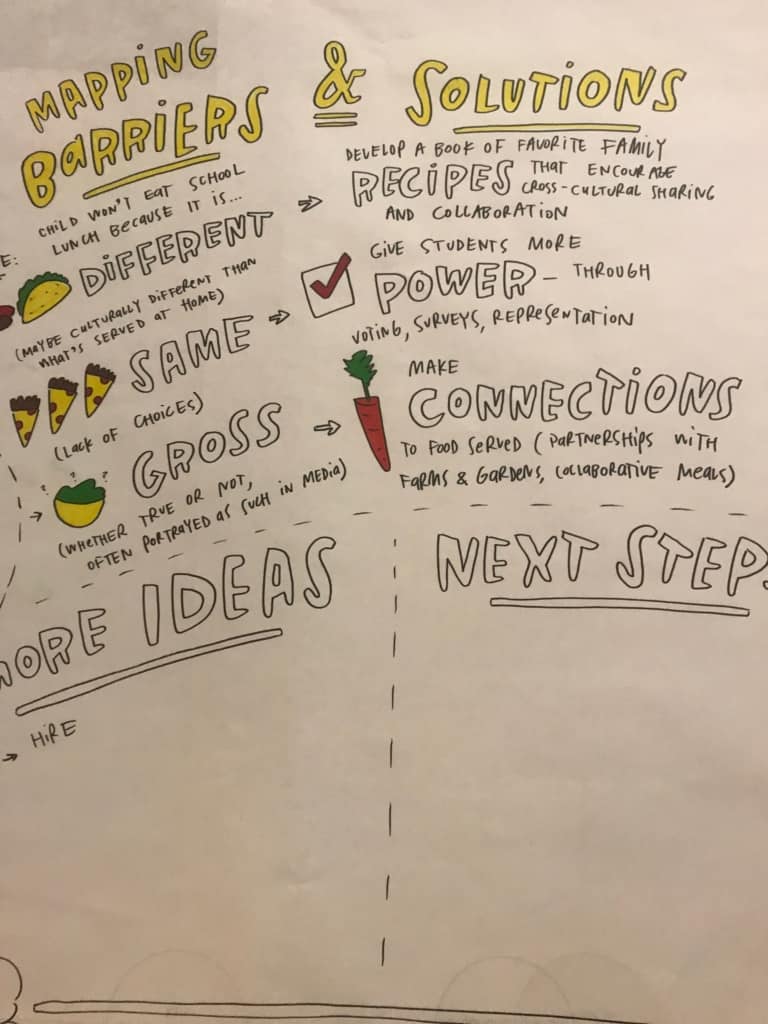

After identifying the many challenges to improving school food, the gathered group participated in a behavioral mapping exercise, facilitated by Food Insight Group, to outline steps to an ideal outcome. Each participant listed the barriers that person would face in achieving that outcome and offered possible solutions.

“Changing the funding model,” suggested Brianna Kennedy, a teacher in Durham County. “This does not sound sustainable, like it’s a private contractor coming into the school instead of it being a part of the school.”

Student solutions focused heavily on having more organic, healthy and local food. “Schools should have more organic foods they grown on farms – tomatoes, lettuce, zucchini, squash,” said Jazon, a student in Durham County. “More organic poultry and veggies.”

The most popular suggestion was having students’ parents create a recipe book of their favorite recipes and train the school nutrition staff how to prepare their meals. Students might recognize school food as food they have at home, and take pride in their meals and exploring recipes of their peers.

This idea was endorsed by many of the adults in the room, who suggested a kickoff festival for each school year where students help prepare the meals in the kitchen with their parents or family members.

Other suggestions included a food truck serving healthy meals outside of high schools, promoting school meals over Instagram and Snapchat, and having students be more involved in growing or preparing the food.

“Taste tests in the classrooms would help. We could do harvest of the month as a way to get kids to try new foods. It’s also a way to get farmers in the classroom “ suggested Anupama Joshi, executive director and co-founder of the Farm to School Network.

Lauren Lampron, principal of Patillo Middle School in Edgecombe County, endorsed that idea. Patillo Middle School already uses taste tests in the classroom, and their health curriculum involves exploring healthy and delicious foods from North Carolina and around the world.

Much of the conversation focused on ways to give students with more agency over their school food choices. Both the students and adults agreed that giving student voice, whether through a survey or participating in growing and preparing the food, is necessary in order to increase participation.

“If the only way to participate in the system is by choosing to eat school lunch or not to eat, you can see why students say ‘Forget it I’m not going to eat.’” said Maureen Berner, professor at the School of Government at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

“If you’re not a willing participant in the system, you’re not really in the system.”