The State Board of Education is planning to send a weighted accountability model for educator preparation programs back to the Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission (PEPSC).

Questions about decisions not to include diversity as a component of the accountability model, as well as concerns about the stringency of the model, led State Board members to decide the plan wasn’t ready to move forward. Though the Board votes tomorrow officially, members made clear they are going to vote to reject the model, effectively sending it back to PEPSC for reconsideration.

“I think we have a good first draft,” said Board member JB Buxton. “Maybe second draft.”

Under the model presented to the State Board, educator preparation programs (EPPs) would be judged based on the performance of an EPP, its retention rate, and stakeholder perceptions.

The new criteria are an attempt to circumvent a potential problem written into Senate Bill 599, which created the commission. The law establishes the sanctions EPPs should face if their scores for these performance measures fall short.

The law as written essentially says that if EPPs fail on any one of the current required accountability standards, they would be sanctioned. If EPPs repeatedly fail, this could lead to probation and eventually revocation of state authorization for the EPPs to produce teachers. All the criteria are weighted equally, so the end result would be that an EPP could do great on two criteria and less great on a third and still face sanctions.

Additionally, the law requires not only that EPPs as a whole meet certain performance targets, but that subgroups do as well. However, some EPPs have relatively small gender, racial, or ethnic subgroups, meaning that poor performance by these groups could lead to EPP sanctions.

The new accountability model would give different weights to different performance targets. Originally, the plan was to have a fourth criteria upon which programs were judged — demographics.

Ultimately, the commission decided to make that criteria a two-year pilot domain so that the state could collect data about the potential consequences of actually incorporating it into the accountability model. Under that plan, demographics wouldn’t impact the score an EPP receives.

Members of PEPSC incorporated diversity only as a pilot because of concerns about how that standard could impact EPPs.

Related reading

Andrew Sioberg, the director of educator preparation for the state Department of Public Instruction, explained last month that there are concerns about the ability of educator preparation programs to reasonably affect their demographic outcomes. For example, if an educator preparation program was pulling from a college population that wasn’t very diverse, then that program might not be able to meet the demographic criteria target through no fault of its own.

Board member James Ford challenged today the notion that diversity should be held back as a real standard.

“Personally, I feel like it’s inadequate, and it’s uninspiring,” he said. “It does not meet the adequacy of the problem.”

He went on to say that while educator preparation programs may not be directly responsible for the diversity of their student population, that doesn’t release them from the responsibility of trying to become more diverse. Spending more time collecting data and talking would only lead to the issue remaining unresolved, Ford said.

“We’re going to talk about this for decades to come because we’re scared to put skin in the game,” said Ford.

The sanctions set forth by the weighted accountability model don’t go into effect until 2021-22. Ford suggested that since sanctions don’t go into effect for a while, diversity should be included in the model and refined as data starts to come in.

Buxton reiterated his concern from last month that the accountability model is not stringent enough. Under the model, no current EPPs would receive level 1, the lowest level on the model and the one that triggers sanctions.

“Frankly, I think we need a tougher accountability system to start,” he said, adding that he’s never seen an accountability model start soft and get tougher.

He also added that he thought more weight should be given to those factors that EPPs most directly control: their students’ performance on the exams they’re required to take by the state.

Because of these and other concerns, State Board members made clear they will vote against adopting the model at tomorrow’s meeting. And they suggested that PEPSC take their concerns into consideration when taking up the model again at their next meeting.

Teacher Attrition

Teacher turnover in North Carolina continues a downward trend, meaning fewer teachers are leaving the classroom.

“The attrition rate for the second consecutive year has declined by a little over half a percentage,” said Tom Tomberlin, director of district human resources at the state Department of Public Instruction.

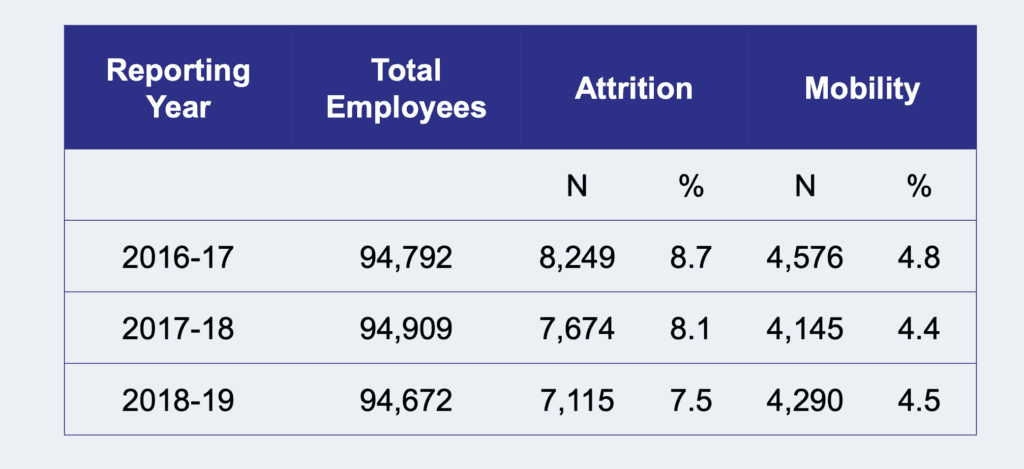

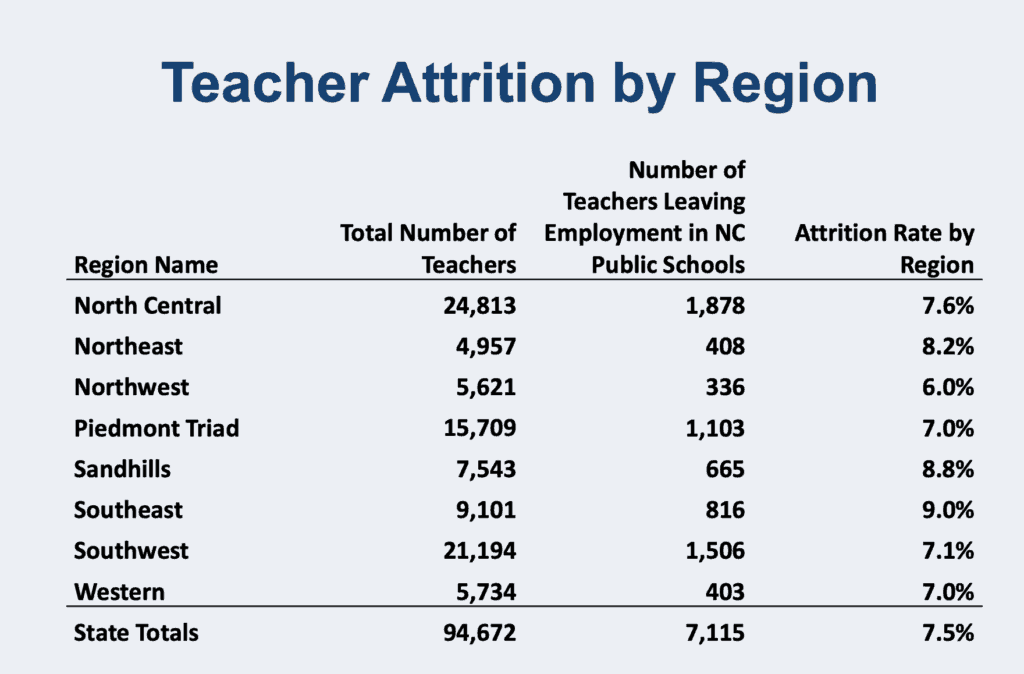

From 2016-17 to 2018-19, the attrition rate — or the percentage of teachers leaving the profession — dropped from 8.7% to 7.5%. The mobility rate — or the percentage of teachers moving between schools or districts — stayed very close to where it was.

Tomberlin said that he couldn’t make any “causal inference” as to why teacher turnover is going down, but he said it indicates where the State Board should be looking when considering how to bolster the teacher pipeline.

“We are not seeing massive exodus from the state,” he said. “It is the incoming pipeline that is the proper focus of the Board.”

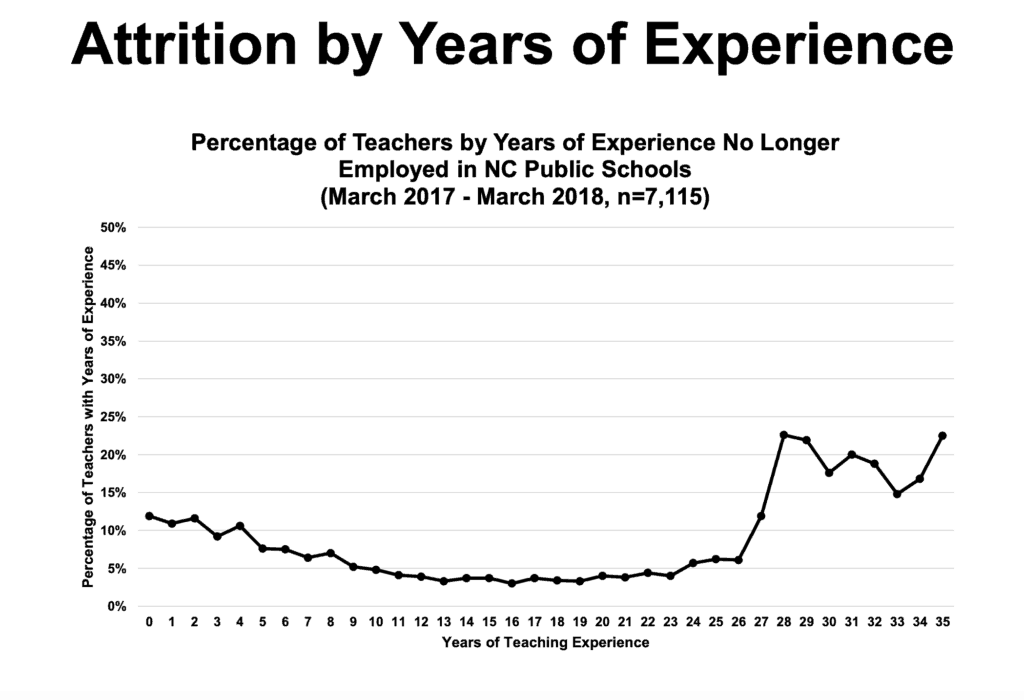

The highest number of teachers leaving the profession are veteran teachers retiring. After that, it is beginning teachers who are most likely to leave.

Tomberlin said that though veteran teachers are retiring, that doesn’t mean the State Board can’t make policy changes that may be helpful in quelling the attrition.

“Can we get them to stay longer?” he asked. “Are there ways for us to entice them to remain in public education?”

He said that when it comes to beginning teachers, the State Board might want to consider whether the state is doing enough to support beginning teachers.

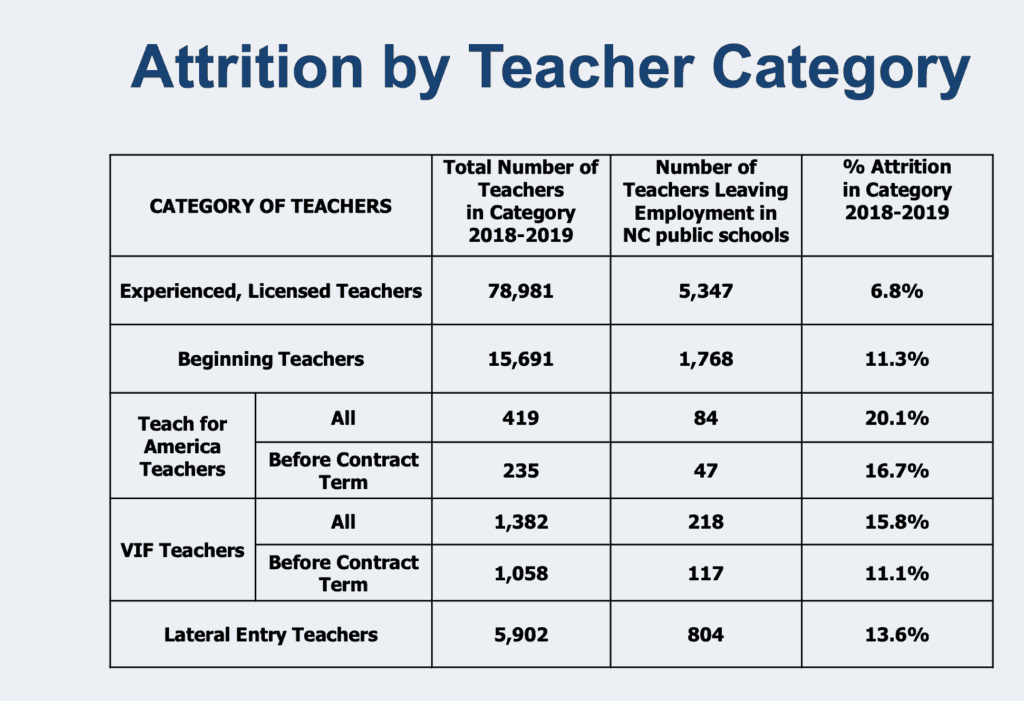

Among the teachers who are most likely to leave, veteran and beginning teachers lead the pack. Then there are Teach for America and VIF teachers, who only sign up to teach for a limited number of years. But Tomberlin also pointed out the attrition of lateral entry teachers. They made up 13.6% of teachers leaving the profession.

“This is becoming the traditional pathway to teacher licensure,” he said. “This number must be addressed.”

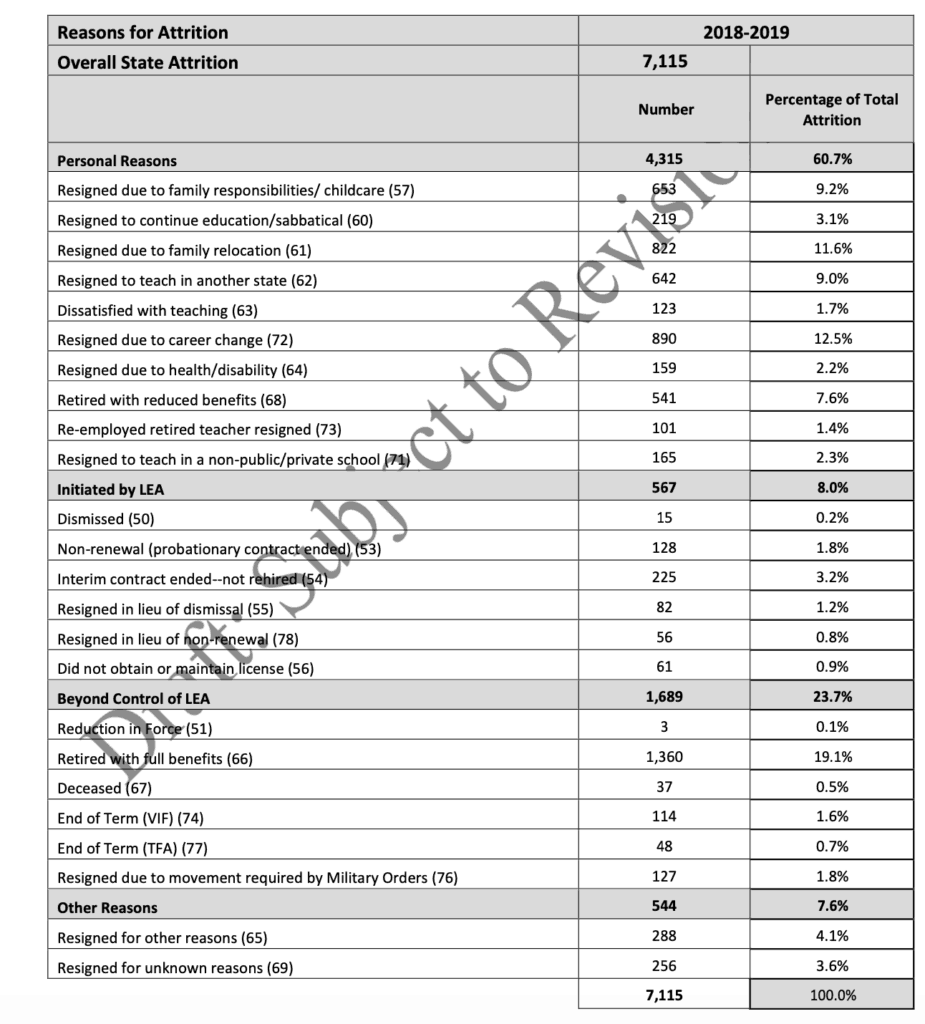

The main reason teachers gave for leaving was “personal reasons,” which encompasses a number of more specific reasons including family, education, dissatisfaction, and career change.

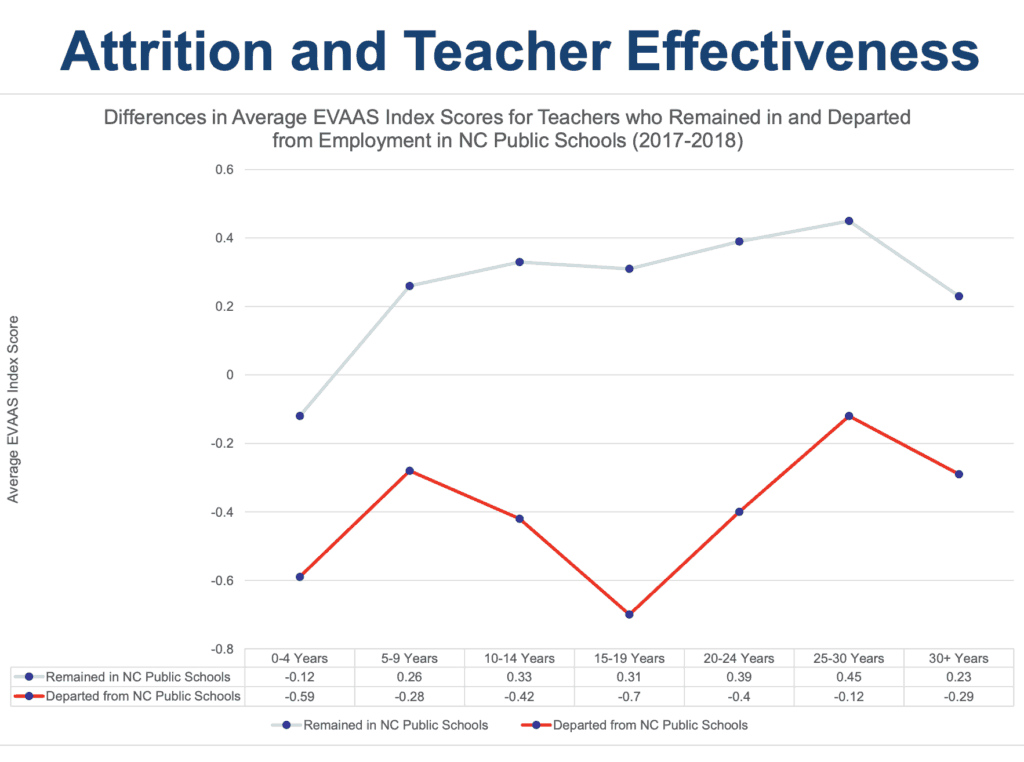

Tomberlin also said that, generally, the most effective teachers in the state are staying in the classroom.

“I am very happy to report that on average, the teacher who remains in the classroom … is much more effective than the teacher who decides to leave,” he said.

Tomberlin also pointed out that attrition is not uniform across the state. There are differences in how many teachers are leaving the profession based on the region of the state in which they teach.

“The east experiences much greater teacher attrition than the west,” he said. “And we need to think of ways we can help those district retain their effective teachers.”

In a press release last week, Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, attributed the low level of teacher turnover to Republican lawmaker actions.

“Republican budgets have given North Carolina teachers the third-highest pay raise in the entire country over the last five years,” he said. “It’s no surprise, then, that higher pay has resulted in higher retention. Teachers should have already received their sixth and seventh consecutive pay raises, but Governor Cooper vetoed that stand-alone pay raise bill.”

The State Board of Education monthly meeting continues tomorrow, and EducationNC will be there covering it.

Recommended reading