Subcommittees of The Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission (PEPSC) have been hard at work over the last year crafting accountability and sanction rules for educator preparation programs (EPPs). But as commission members delved into the details, they realized that the requirements written into the law that established PEPSC could end in a result where many successful EPPs face sanctions for relatively minor failings.

First, some background.

PEPSC was created by Senate Bill 599 in 2017 and tasked with coming up with rules related to the preparation, licensure, and accountability of teachers in North Carolina.

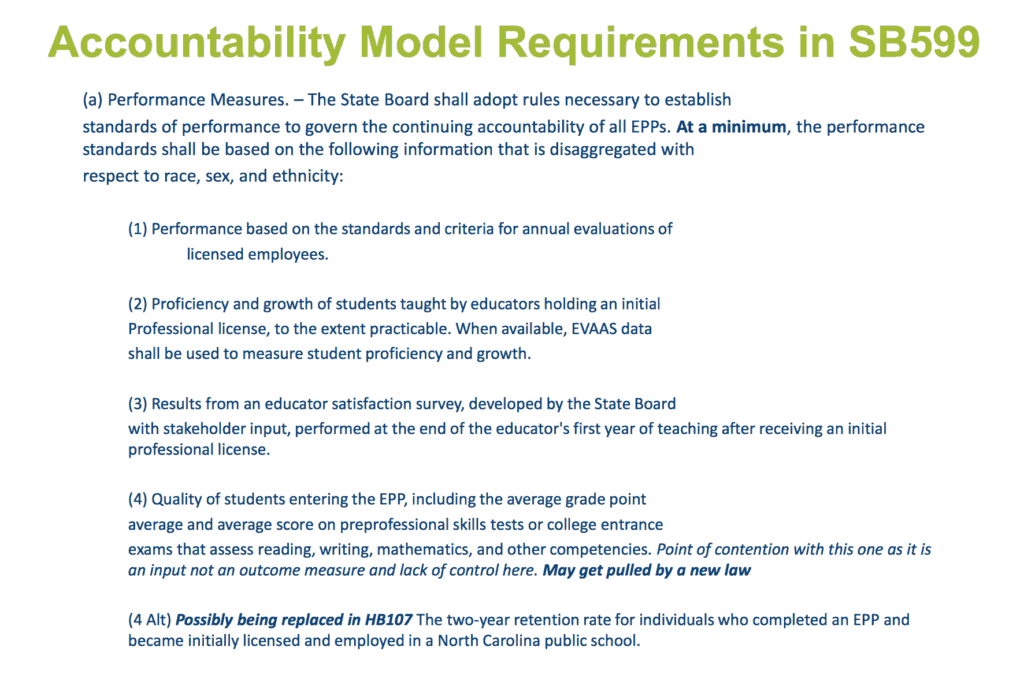

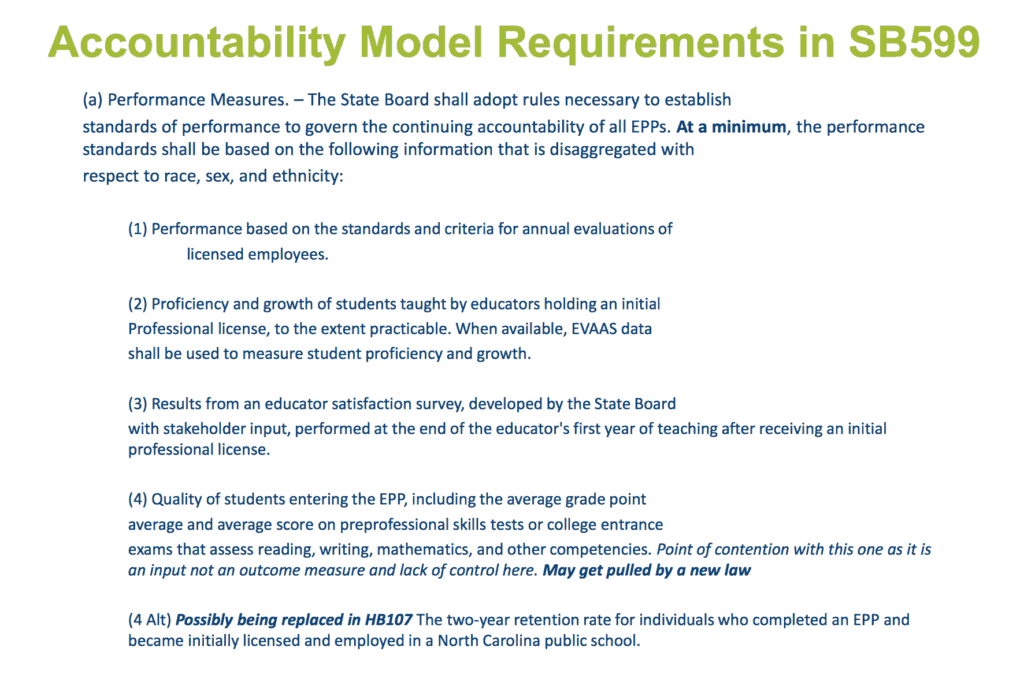

SB 599 laid out in great detail the accountability models that educator preparation programs would be held to but left the work of crafting the fine points to PEPSC.

Using that as a springboard, subcommittees of PEPSC came up with an accountability model that could encompass four or five standards and presented them to the full PEPSC commission yesterday.

- Standard 1: Teacher Evaluation

- Standard 2: Teacher Impact

- Standard 3: Stakeholder Perceptions

- Standard 4: Quality of Students

- Standard 4a: Candidate Employment

- Standard 5: Quality of Preparation*

Standard 4a is there because changes to the law currently being considered in the General Assembly might necessitate switching out 4a with 4. And standard 5 is not required by law, but the subcommittees of the commission thought it might be a good addition. Ultimately, whatever rules PEPSC comes up with on accountability and sanctions would have to be approved by the State Board of Education.

Now, the problem.

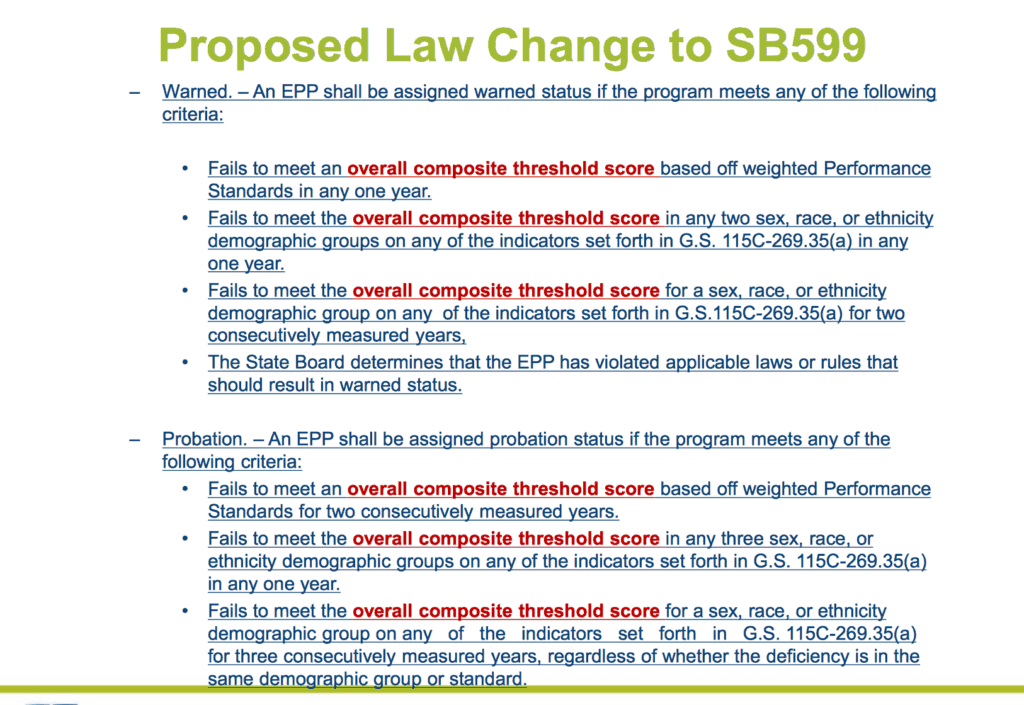

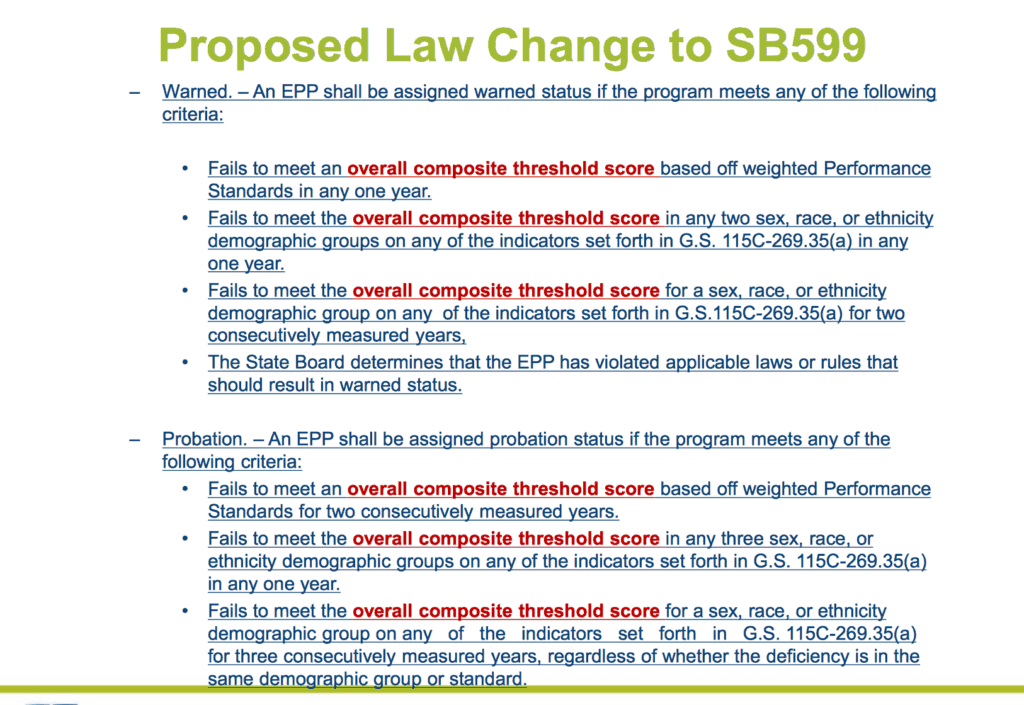

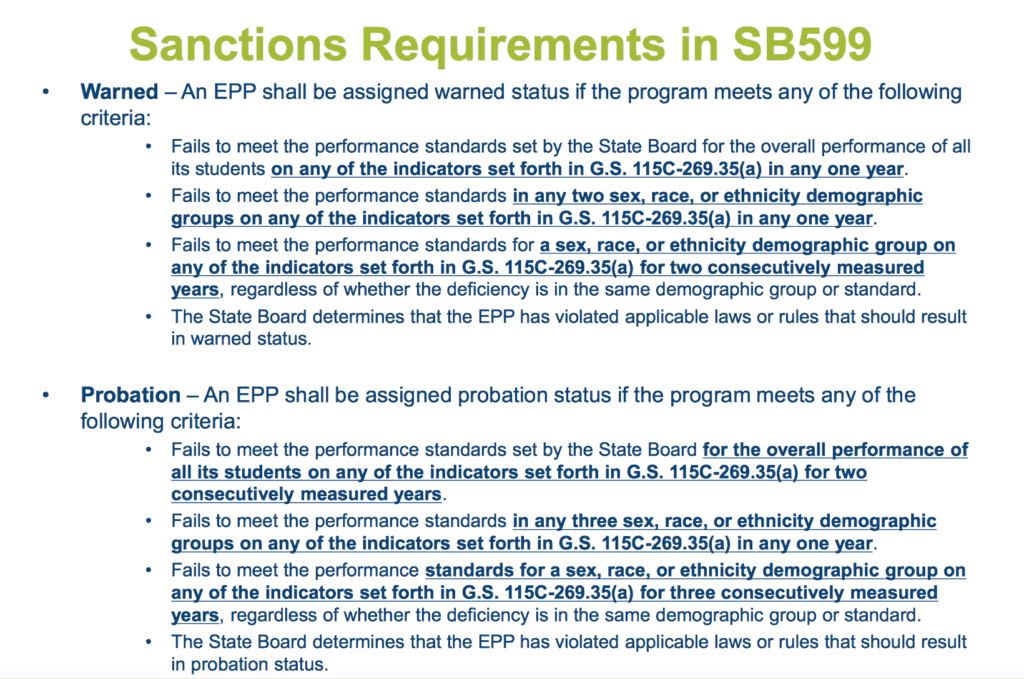

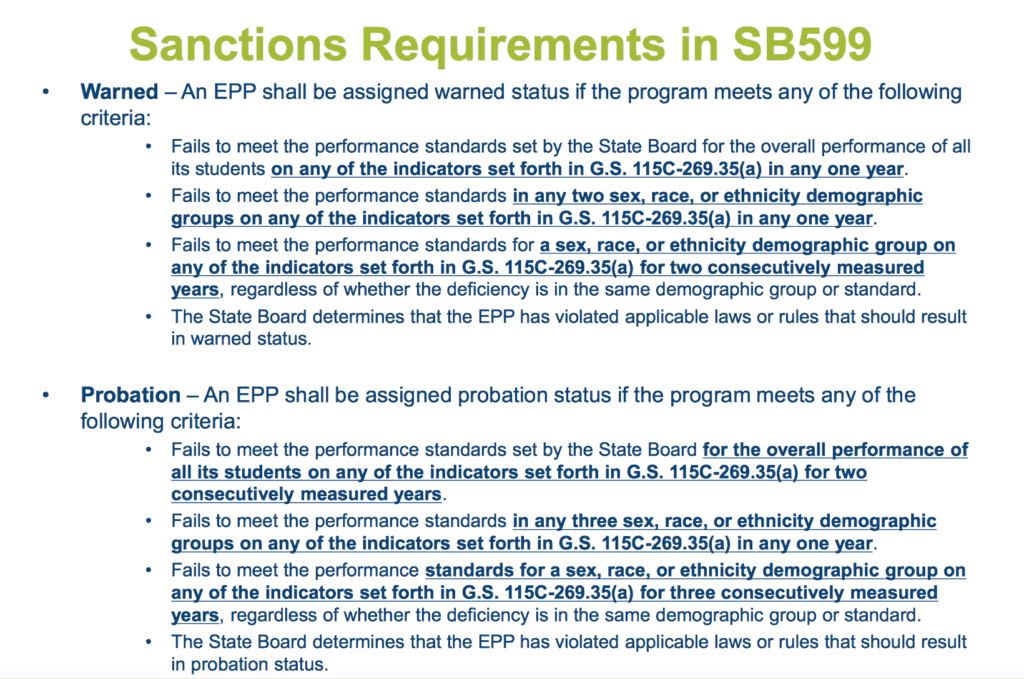

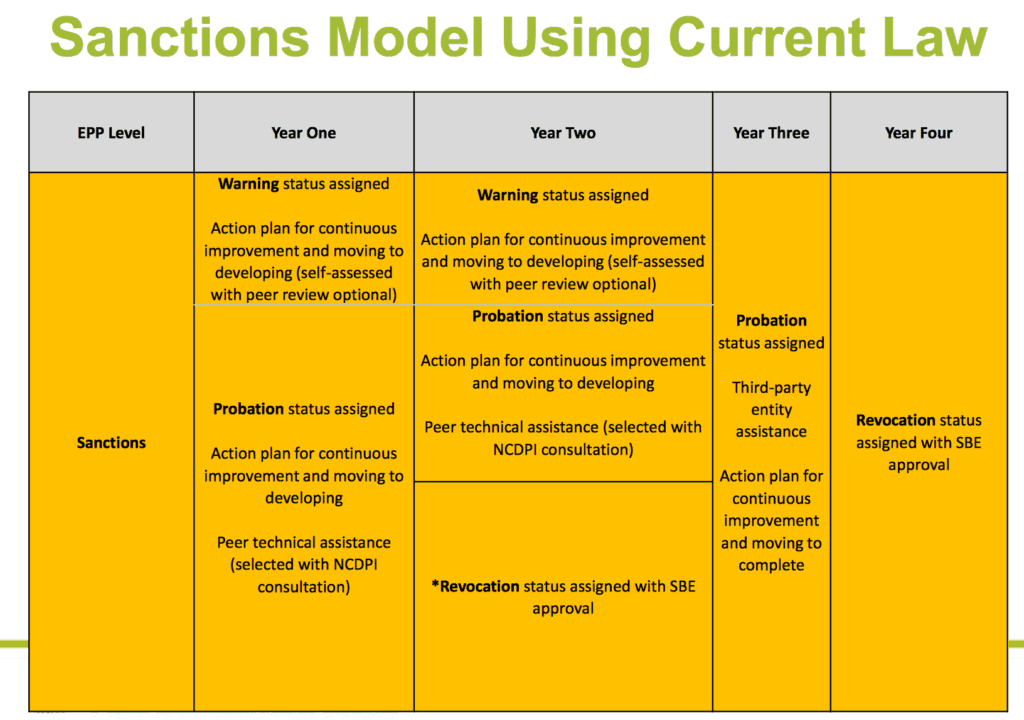

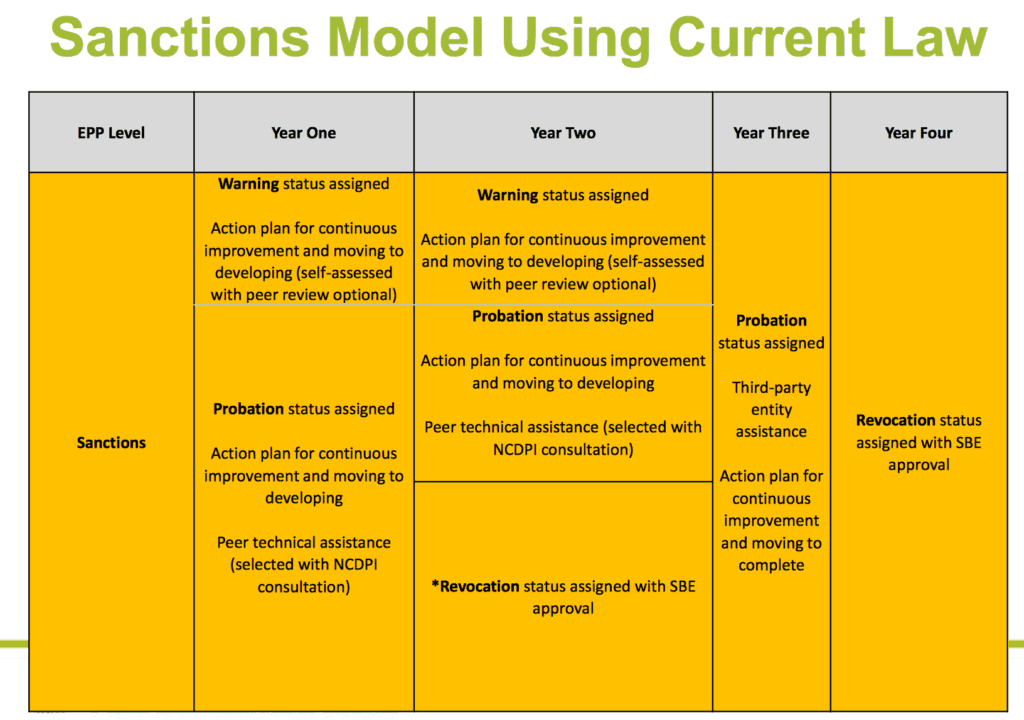

In addition to laying out the accountability models, SB 599 also laid out the sanctions that would apply to EPPs if they failed to meet the accountability measures.

Pay particular attention to the bold parts. The law as written essentially says that if EPPs fail on any one of the required accountability standards, they would be sanctioned.

“You can knock it out of the park in three out of four, and be just below the threshold on the fourth, and be sanctioned,” said Greene County Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller, chair of PEPSC.

Furthermore, if any two of the subgroups of the EPP — be it subgroups of sex, race, or ethnicity — failed one of the standards in one year, the EPP would be sanctioned. And if one subgroup failed any one standard for two consecutive years, the EPP would be sanctioned. The sanction in these last three cases would be a warned status.

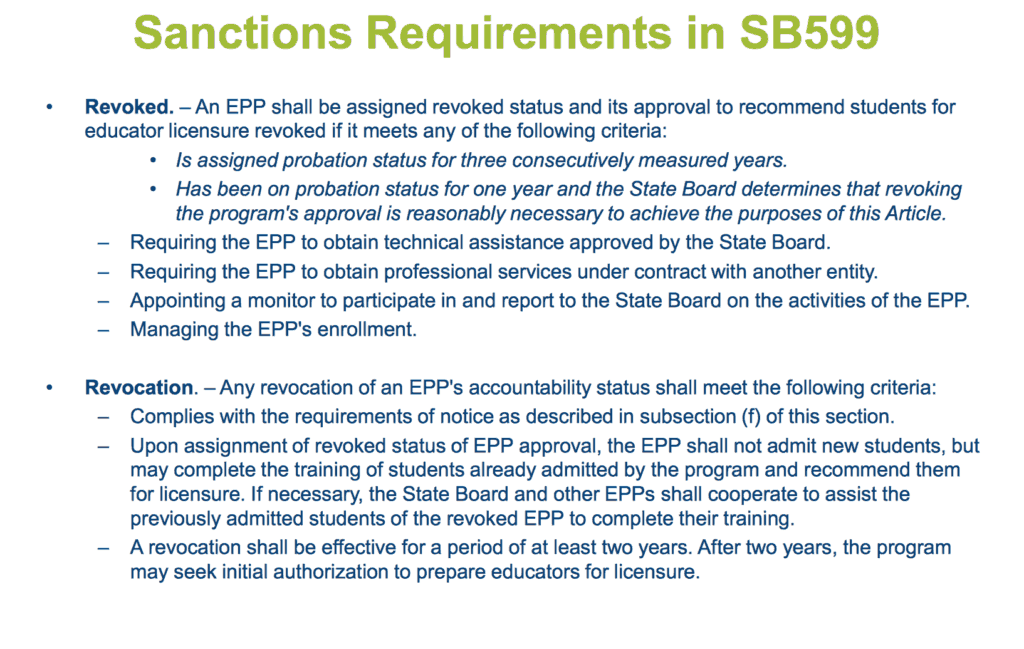

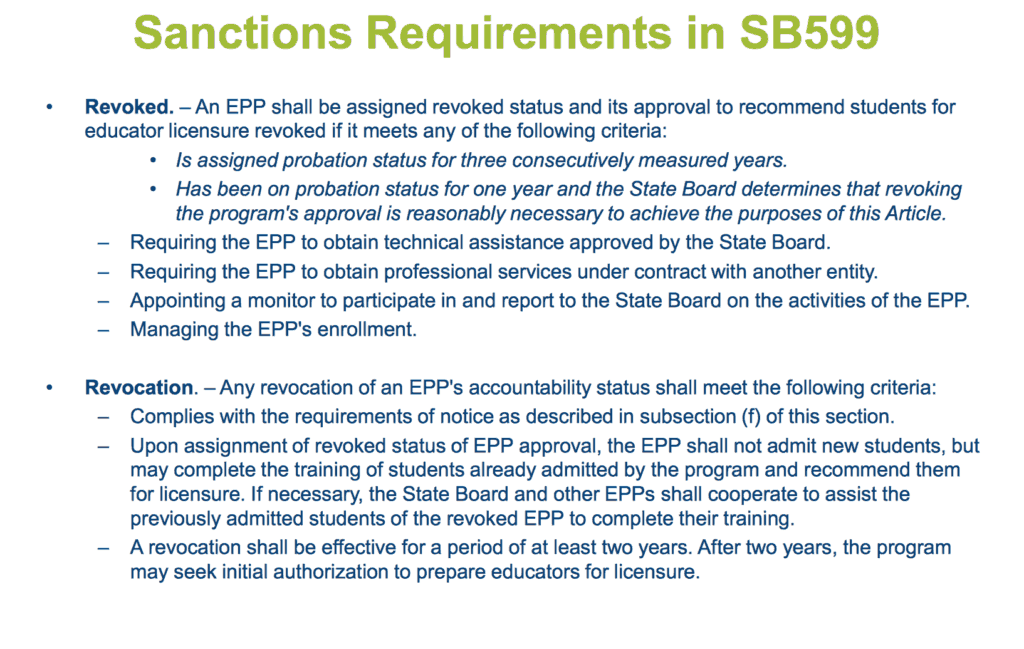

Probation would come if the EPP failed on any standards for two years in a row, or if three subgroups failed any standard in a year, or if one subgroup failed any standard for three years in a row. After probation comes revocation.

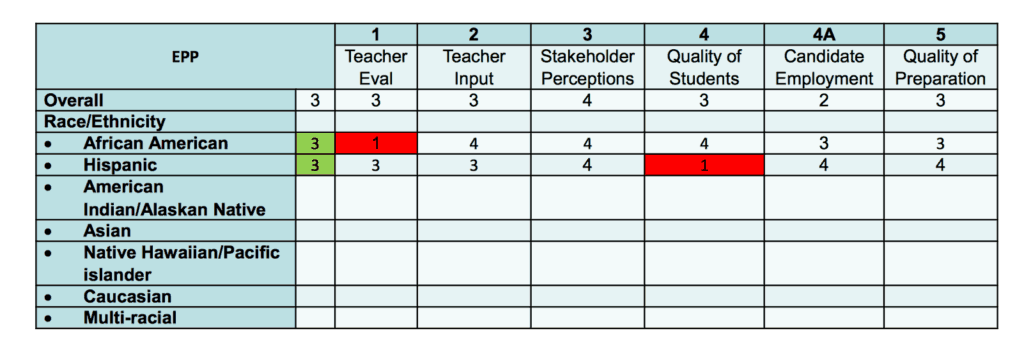

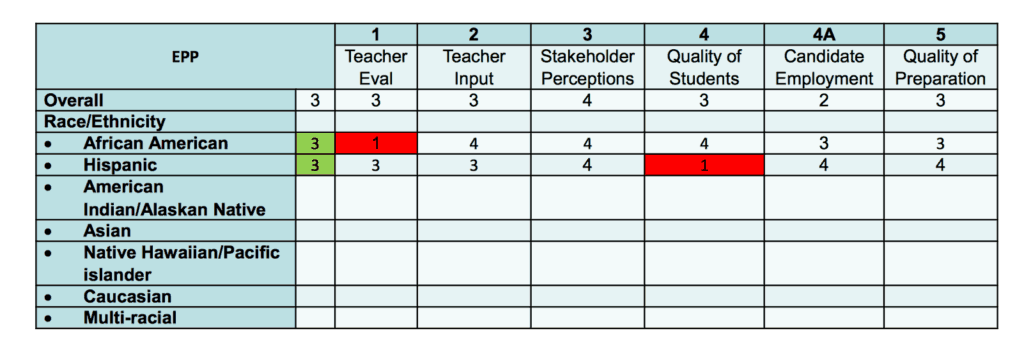

The chart below illustrates the issue. Taken together, African American students in an EPP that are evaluated poorly (receive a 1 out of 5) in the teacher evaluation standard and Hispanic students performing poorly (receive a 1 out of 5) on the quality of students standard could lead to an entire program being put on warned status even though those subgroups performed well overall (3 out of 5).

“Virtually everybody is going to be sanctioned on something according to the legislative component,” said commission member Van Dempsey, dean of the Watson College of Education at UNC Wilmington.

And, an EPP with a small number of students from any particular subgroup could be penalized for the low performance of relatively few students. Dempsey said his program educates about 300 potential teachers a year, most of whom are white and female. That means the performance of subgroups could have a disproportionate impact on his EPP as the law is written. Since the ultimate result of sanctions can be the loss of the ability to turn out teachers, the result could be a net negative for the teacher pipeline in North Carolina.

“I cannot imagine that one of the goals of the General Assembly was to create a possibility that would reduce the number of teachers that were coming out of EPPs,” Dempsey said.

Another issue is that PESPC may not want all the standards to be weighted the same. So, for instance, they may want teacher evaluation to count for more than teacher input. But, because the sanctions are so stringent and inflexible, the law essentially precludes PEPSC from treating any required standard different from any of the other ones.

Ultimately, PEPSC voted yesterday to approach lawmakers with a request to change the law so that the commission could have more flexibility in the standards and so the sanctions wouldn’t be so harshly applied.

Andrew Sioberg, director of educator preparation at the state Department of Public Instruction, said it is unclear whether lawmakers really wanted such harsh sanctions or if the law was just worded incorrectly.

“It could be that the intent of the law is to really hold everybody to account on all those different subcategories, and to that extent it would really cause some consternation and some angst among the EPPs,” he said. “It could be that they just didn’t see the disconnect between what was going on in the sanction side and what was going on in the accountability side.”