Part I: Defining the terms

Self-governing schools and parental choice often go together

A major argument for self-governing schools is that school personnel are in a better position to understand and respond to the needs of their students than are more distant policymakers at the district or the state level. By analogy to separate plants or outlets within a private-sector company, it makes sense to locate operating responsibility as close to the ground as possible in order to promote the most productive use of the available resources. Local managers can respond flexibly and quickly to particular challenges that arise at the local level.

As long as the average preferences of members of local school communities differ one from another, self-governing schools have the potential to generate educational benefits.

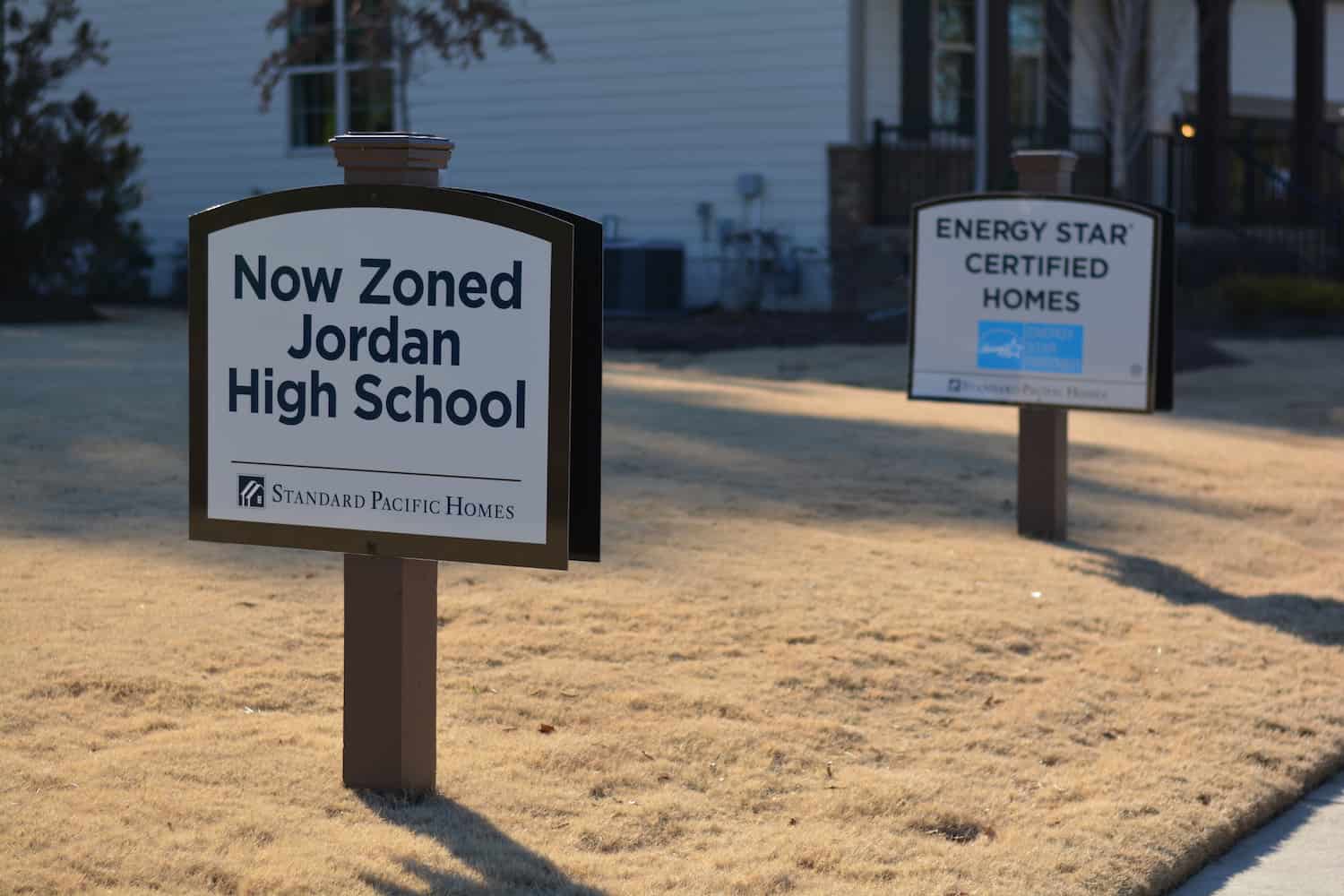

In the education context, the case for self-governance often extends beyond productive efficiency to responsiveness to local interests in education, interests that may differ across local communities. One community, for example, may be most interested in the development of the academic skills necessary for pursuit of a college degree and another in the balance between academics and other activities such as sports or vocational programs. Similarly, a community of African-American or Hispanic families might want somewhat different things from their local school than a community of white families. As long as the average preferences of members of local school communities differ one from another, self-governing schools have the potential to generate educational benefits – a fact that holds independently of whether parents are allowed to choose a school other than their assigned school. At the same time, once schools are empowered to differentiate their offerings, it is hard to defend a policy of assigning children to specific neighborhood schools if other schools would provide a better educational fit for the particular child. Consequently, policymakers typically combine self-governance of schools with expanded parental choice of school. U.S. charter schools are illustrative. States that enable charter schools give them substantial operating autonomy, but at the same time make them schools of choice in the sense that no children are assigned to them. Instead, families have to choose to enroll their child in a charter school.

If one starts with the goal of expanding parental choice, one ends up with the same conclusion. Among the various justifications for supporting expanded parental choice of school is the expectation that parents will use that flexibility to choose schools whose offerings are better matched to the educational needs or preferences of their children than otherwise would be the case. If the only difference among schools is the socio-economic status of the students they serve, parental choice will inevitably foster inequality. If schools are empowered to differentiate themselves one from another through the programs they offer, however, parental choice has more potential to improve the educational fit. Moreover, when combined with school autonomy, parental choice may induce schools to operate more efficiently than they otherwise would as they try to attract students by responding to parental demands. In sum, for parental choice to work well, and not simply to promote inequality, schools must have significant autonomy over their operations so that they can differentiate their programs and offer them in an efficient manner. So once again, parental choice and school autonomy go together.

The private and public, or collective, interests in education

Schooling clearly generates benefits for the children who receive the education and their families. These benefits, which are often referred to as private benefits, are in the form of both consumption and returns on investment. The children themselves benefit from being in a safe, engaging and potentially enjoyable school environment and their parents benefit from avoiding child care expenses and obtaining satisfaction from their children’s development. Returns on investment in education come in the form of access to better jobs with high wages, more opportunities for advancement, and lower rates of unemployment. In addition to these labor market returns, educated individuals tend to have better health, to be more civically engaged, and to have more fulfilling lives. These private benefits – both the consumption and the investment benefits – can also be categorized as intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic benefits arise when education is valued for its own sake, such as the pleasure of being able to solve a complex problem or appreciate artistic expression; and extrinsic benefits arise when education serves as an instrument for the attainment of other valued outcomes, such as the potential for the recipients of education to seek higher paying jobs and more fulfilling careers than would otherwise be possible. Regardless of the classification, it is clear that education provides a variety of different types of private benefits, many of which accrue long after the students have been in school.

The benefits of schooling, however, accrue to more than just the child and the child’s parents.

The benefits of schooling, however, accrue to more than just the child and the child’s parents. Hence the public interest in education is not simply the sum of the private benefits. Among the public benefits of schooling are short-run benefits for others that arise from keeping idle children off the streets and away from crime or other antisocial behaviors, and the longer-run benefits of having an educated citizenry capable of participating effectively in the democratic system and a workforce that is productive and innovative. These longer-run benefits accrue not only to the residents of the local community in which the children live, but also to the broader society. Low educational investments in students in one jurisdiction have spillovers to other jurisdictions because people move across jurisdictions, citizens participate in the political life of the nation as well as that of their local community, and the productivity of one geographic area of the country can affect overall productivity.

Given the importance of education to a child’s life chances, there is a morally based collective interest in assuring that all children have access to a quality education.

Another public or collective interest takes a different form. Although it is individuals who have interests, such interests become collective when they are shared. Most people, I suspect, would agree that as a society, we have a shared interest in providing all children, regardless of the income or inclinations of their parents, an opportunity to flourish. After all, the fact that a child is growing up in a low income or dysfunctional family is not the child’s fault, nor can the child do anything about it. Given the importance of education to a child’s life chances, there is a morally based collective interest in assuring that all children have access to a quality education. In addition, we all have a shared interest in raising children to treat other children as moral equals. Regarding others as equals does not require that we care about strangers as much as we do about our family members, or ourselves. Nor does it rule out judgments that people are unequal with respect to attributes like strength, intelligence, or virtue. It means simply that we treat all people as fundamentally equal in moral status. In the U.S. context, that is particularly salient with respect to race. The experience of slights grounded in assumptions of racial superiority – as also with gender, sexuality, or physical or mental abilities – undermines the self-respect and self-confidence of the slighted, making it harder for them to flourish. The impact is worse if the slighted themselves share the attitude that they are inferior, or, while not sharing it, are nonetheless disposed to accept the slights as their due. What this capacity implies for education policy may differ across cultures. For example, given the U.S. history of slavery and Jim Crow laws, the Brown v. Board pronouncement that racially separate schools are not equal provides the basis for a collective U.S. interest in avoiding racially segregated schools.

Importantly, families and their children have a strong and legitimate interest in the quality of the education that the children receive. That is, they have strong private interests. Although the collective interests in high quality education for all students may be equally or perhaps more important overall – and are what justify public funding and making schools compulsory – they are typically far less salient to individual families than are the private interests. It is this imbalance that creates the challenge of promoting the public interest in the context of self-governing schools and parental choice.

Next >> Part II: Durham Public Schools and the growth of charter schools

Editor’s note: In sharing Professor Ladd’s article with you, it was not the intention of EdNC to cast anyone’s school in a negative light. My son, Hutch Whitman, applied and was accepted to Research Triangle Charter School and he almost went there. It’s a great school. As the principal notes, “[the school has] improved the percentage proficiency across math and biology in one year by 213% for economically disadvantaged students, 106% for African-American students, and 143% for Hispanic students.” EdNC hopes to be able to share the story of the good work this charter school is doing with its students and the community going forward.