Part II: Durham Public Schools and the growth of charter schools

With its total population of 234,000, Durham County in North Carolina highlights the challenges facing a district that has historically had to grapple with issues of race and that now is confronted with new challenges posed by the growth of charter schools, the quintessential example of self-governing public schools of choice in the U.S. Until the early 1990s, the county’s schools were split into two districts, a virtually all-black city district and a far whiter county district. At that time, strong city leadership consolidated the two into the current county-wide district known as the Durham Public Schools (DPS), with the goal of providing a sounder educational basis for county-wide economic development. The current school population is 50 percent black, 25 percent Hispanic and about 20 percent white. In an effort to keep white students in the school system, which has been experiencing moderate growth in recent years, DPS has provided various forms of choice for parents in the form of magnet and year-round schools and has, in practice, had a flexible transfer policy that often enabled parents to opt out of their assigned schools.

The situation is now changing because of state legislation in 1996 that enabled 100 charter schools to be established throughout the state, with the State Board of Education as the sole authorizer. The cap of 100 schools remained in place until 2011, at which time a conservative newly elected Republican Legislature eliminated the cap in part as a means of assuring that the state would be eligible for $400 million in federal aid through the competitive Race to the Top Program. Since then the number of applications for charter schools has grown dramatically. As of the 2013-14 school year, 127 charter schools were operating throughout the state with an additional 26 approved to start for the 2014-15 school year and another 71 applications submitted for the 2015-16 school year. Durham County has proven to be a popular location for charter school operators partly because of perceived concerns about the low performance of the students in the public school system and partly because the county relatively generously supplements state funding for schools with county-raised tax revenue. Such funding is appealing to charter operators who receive the average per pupil funding available to the students based on the district in which they live. As of 2013-14, the county had 8 charter schools serving 12 percent of the student population, a proportion that could easily double in the next few years as the state approves more charter schools.

Moreover, in any case, even if it were feasible to reduce [costs] in proportion to the loss of students, the school system would not be in a position to do so because of its responsibility for assuring a school for every student in the district.

The emergence of charter schools poses multiple challenges to the public interest in Durham. The first is a fiscal challenge. As students opt out of the traditional public schools in favor of charters, the traditional school system has to transfer funds to the charter schools. That would not pose a fiscal problem for the Durham Public Schools if it were able to reduce its own spending in line with the loss of students. In fact, though, that is not possible. Some costs, such as school facilities or the infrastructure needed to serve students with special needs, are fixed in the short run and are not easy to cut. Moreover, in any case, even if it were feasible to reduce them in proportion to the loss of students, the school system would not be in a position to do so because of its responsibility for assuring a school for every student in the district. The problem here is that students who opt out of the public school system for a charter school may need to return to the traditional public system either because the charter school is not a good fit for them or because the charter school itself shuts down. As a result the traditional system has to maintain the flexibility to assure places for them, a responsibility that does not extend to the charter schools.

In addition, charters typically serve lower proportions of the most expensive-to-educate students, such as students with the more serious forms of special needs, or from economically disadvantaged families. Although some charters specifically orient their programs to such students, others make it difficult for disadvantaged students to enroll by not providing transportation or not offering subsidized lunch programs. Hence, while the district transfers funds to the charters based on average per-pupil funding, it is left with a group of students who require above-average spending. Further, whenever the charter schools attract students who otherwise would have attended private schools, they impose new costs on the districts. A recent careful analysis of the current fiscal burden placed on the Durham public schools is about $2000 per charter school student, although the precise amount varies depending on the assumptions made.

Another challenge to the public interest arises because the growth of charter schools interferes with the ability of the district to plan for facilities and programs.

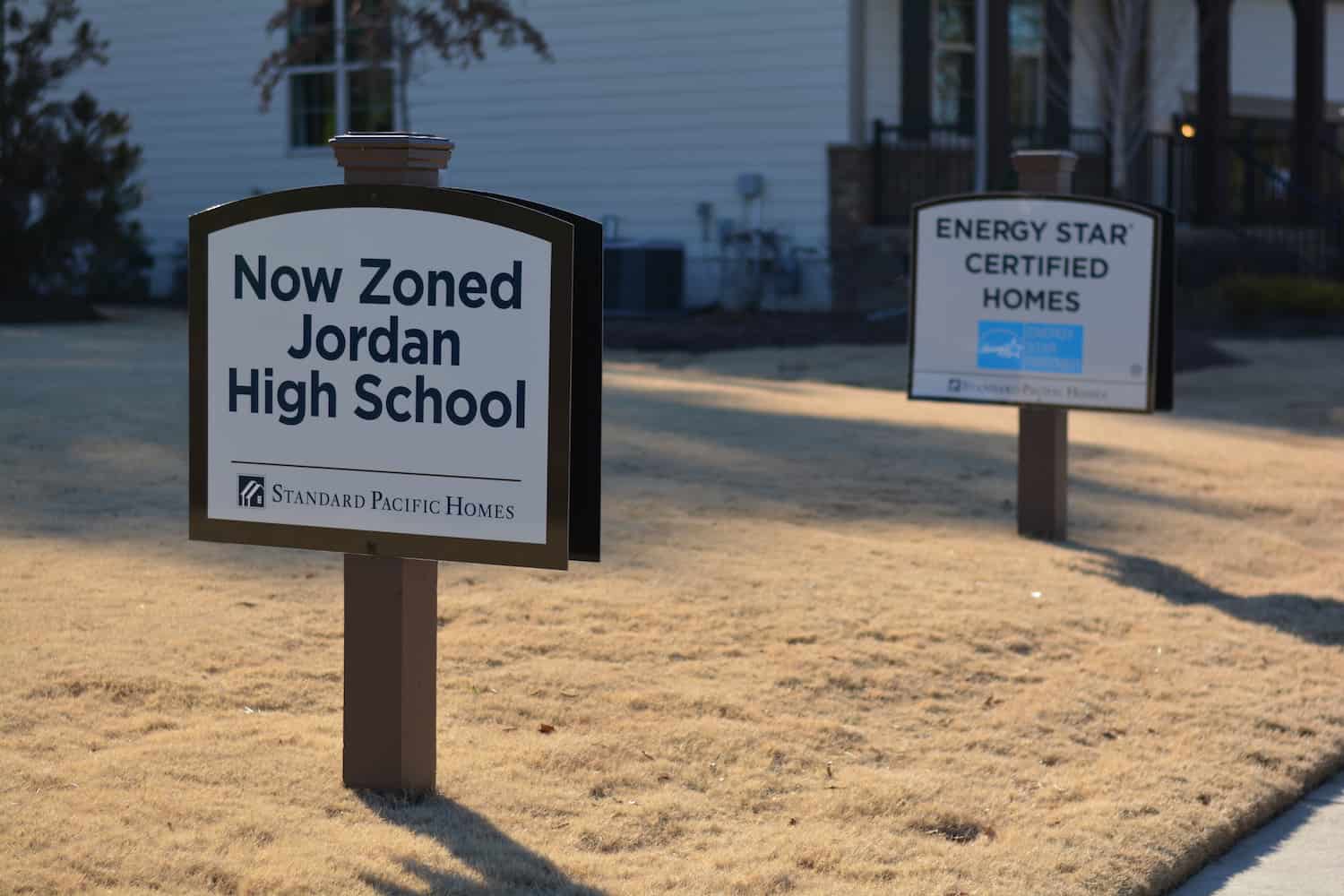

Another challenge to the public interest arises because the growth of charter schools interferes with the ability of the district to plan for facilities and programs. Recall that the State Board of Education is the sole authorizer of charters. Although the districts never had a lot of input into the process, recent legislation has eliminated completely any statements from them about the potential impact of new charter schools on their operations. In the past, DPS could make reasonable projections about the size of the public school population and could plan facilities and programs accordingly. Planning is essential with respect to facilities because of the lead time needed to assure their completion in a timely manner. Many investments, such as the development of sophisticated science programs within high schools, also require long-term planning. As more students opt out of the traditional public schools for charter schools, DPS is left not knowing how many students it will need to serve and how best to meet their needs. The 2012 establishment of a science-tech charter school in nearby Research Triangle Park illustrates the problem. Though the new charter school may be great for the students who attend it, few of whom are likely be disadvantaged, it interfered with the District’s development of a major new science-tech program within an historically African American high school located near the Research Triangle Park. Presumably the public interest would be better served if the District had a greater role in the establishment of and location of new charter schools.

A third threat to the public interest is the impact of charter schools on the racial segregation of schools in Durham. Since the merger of the city and county school districts in the early 1990s, the School Board has worked hard to integrate the schools, albeit not fully successfully given the large proportion of African Americans and Hispanics in the county and the Board’s relatively lenient transfer policy. As of the 2011-12 school year, 41 percent of the students in traditional public schools were in schools that were almost exclusively minority (defined as having 90-100 percent nonwhite students). Moreover, only 1.4 percent were in schools in which the proportion of nonwhite students was less than 30 percent. Contrast that, however, with the distribution of charter school students in that same year. Among them, an even higher percentage (51 percent) were in schools with almost no white students, and 32 percent were in schools that had less than 30 percent nonwhite students.

This asymmetry of parental preferences means that charter schools that aim for an even mix of blacks and whites are likely to tip toward being exclusively black, while those that are primarily white will remain so.

My earlier analysis (with Robert Bifulco) of parental preferences for charter schools in districts across the state provides an explanation for this racial bifurcation of the charter schools. According to our estimates, black parents at that time were looking for charter schools that were between 40 and 60 percent black while white parents were seeking charters that were less than 20 percent black. This asymmetry of parental preferences means that charter schools that aim for an even mix of blacks and whites are likely to tip toward being exclusively black, while those that are primarily white will remain so. Moreover, within Durham, the charter schools increasingly appear to be serving as a means for white families to avoid the heavily non-white traditional public schools. While in 2001 less than 10 percent of the county’s charter school students were white, by 2012 that percentage had tripled to more than 32 percent, a percentage that far exceeds their share in the traditional public schools.

One obvious way to address these challenges would be to try to get the two sectors – the charter sector and the traditional public school sector – to collaborate in the interests of serving all children in the county rather than competing with each other for students and the funding that follows them. That would mean, among other things, that the charter schools would have to take more responsibility for educating their fair share of expensive-to-educate students and the District would have to make a number of services, such as professional development or transportation available to the charter schools, presumably for a fee. Recently the chair of the DPS School Board has supported a proposal to set up a task force of representatives from the Board and the charter schools to develop a common enrollment system, a common school accountability framework, and a shared transportation and meal program. In addition, the task force would be charged with establishing a common lobbying effort at the state level directed toward giving the local district more control over the charter schools within the district. Collaboration of this type, however, is likely to prove very difficult and the chances of it being successful are limited at best.

One of the few potential benefits to the existing charters comes from the possibility that the resulting agreement might somehow help to slow the entry of new charter schools into the county that would otherwise dilute the demand for their schools.

It is difficult in part because of the current hostility and antagonism between the two types of schools and also because, in contrast to the traditional public schools which are organized under a single school board, the charter schools are separate entities not organized into a coherent unit. Even if representatives of the two types of schools could be brought together, some of the charters would have limited incentive to participate. As self-governing schools they would have to put the general public interest above the more narrow private interests of many of the parents they serve. That is particularly difficult for charter schools serving relatively advantaged students whose parents may have chosen the charter school specifically because it was not serving large numbers of disadvantaged students. For other charters, it could mean subjecting themselves to more regulations or bureaucratic decision making that would interfere with their governing philosophy or with the financial or other interests of their sponsors. One of the few potential benefits to the existing charters comes from the possibility that the resulting agreement might somehow help to slow the entry of new charter schools into the county that would otherwise dilute the demand for their schools. At the same time the potential for new charter schools to enter the Durham market, as is inevitable during the next few years, greatly reduces the incentive for the established schools to participate in agreements that might reduce their ability to compete successfully with new charters not bound by the same agreements.

Other support from this conclusion that collaboration faces formidable obstacles comes from the experience of compacts between 16 districts and their charters that were supported by a 2010 initiative funded by the Gates Foundation. Bolstered by $100,000 grants, each city signed a formal compact with its charter schools to undertake a variety of cooperative activities. Despite some noteworthy progress in a few places in a few activities, a 2013 interim report showed limited progress in most of the compact cities. Among the 15 districts that had agreed to set up shared service agreements, for example, only three had made progress. Similarly, among the 14 districts that had agreed to improve access to and the quality of special education districts, only five had made significant progress, and among the eight districts that had agreed to implement a common and coordinated enrollment system only four had made progress. The gulf between a district system that is responsible for serving the educational needs of all students and sets of independent charter schools that are oriented primarily to the students they serve is simply too difficult to overcome in many cases.

Next >> Conclusion

Editor’s note: In sharing Professor Ladd’s article with you, it was not the intention of EdNC to cast anyone’s school in a negative light. My son, Hutch Whitman, applied and was accepted to Research Triangle Charter School and he almost went there. It’s a great school. As the principal notes, “[the school has] improved the percentage proficiency across math and biology in one year by 213% for economically disadvantaged students, 106% for African-American students, and 143% for Hispanic students.” EdNC hopes to be able to share the story of the good work this charter school is doing with its students and the community going forward.