How are water and wastewater infrastructure a hidden challenge for rural North Carolinians? Community water is both privately and publicly owned, but as rural economies have morphed, so has the capital for managing public utilities.

In the last of the NC Rural Center and Rural Counts‘ virtual advocacy speaker series, Rural Talk, panelists and policy makers discussed the complicated reality of water and wastewater infrastructure in rural North Carolina.

Rose Vaughn Williams, of the North Carolina League of Municipalities, said, “Like roads and bridges, this [water] is hard infrastructure — pipes in the ground for delivery systems and treatment facilities. The challenge we face today is that our rural communities and their economies are changing, and have changed, and in some places significantly.”

Some think agriculture is the industry that fuels rural economies, but that isn’t always the case. Manufacturing plants have moved in and out of rural North Carolina and with that movement have left infrastructure that needs support. This burden can fall on an aging population with fixed incomes or in areas with declining population.

“So you have fewer people who can pay the water bills necessary to maintain the system, and certainly few people who are able to pay as much as necessary,” Williams stated.

According to North Carolina’s Statewide Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Master Plan, water and wastewater infrastructure needs for the state range from $17 to $26 billion over the next 20 years.

Panelists for this webinar included Gloristine Brown, mayor of Bethel; Kim Colson, director of the Division of Water Infrastructure at North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality; and Sharon Edmundson, director of the fiscal management section of the State and Local Government Finance Division at the North Carolina Department of State Treasurer. At the end, two state legislators joined the call — Sen. Don Davis, D-Greene, and Rep. Chuck McGrady, R-Henderson.

The previous four Rural Talk discussions covered broadband access, small businesses, health, and housing. The fifth and final discussion on water and wastewater infrastructure can be found below.

How did we get here?

Many of the water systems we see now in rural areas started off as privately owned and began as a result of community population growth. With water came the need for sewer systems and water treatment facilities. A lot of that work was paid for by grants and subsidized loans, Colson said. Those funds have dried up and are nowhere near what is needed to support the system.

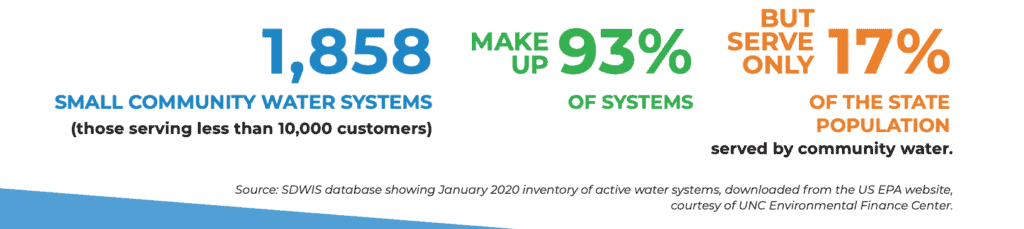

The business model for water doesn’t comply with smaller governments. Fewer people are paying for service and these governments have less money, making it difficult to cover operation costs and stay in compliance with regulations. A declining customer base “makes it very difficult for these systems to be viable,” Edmundson said.

“Small systems have lost a lot of their commercial base, and what’s left of their residential base often uses just the bare minimum of water, which reduces the amount of income that you get from those customers.” – Sharon Edmundson, NC Department of State Treasurer

She also reflected that one of the first things to get cut from the budget is maintenance, which results in costly emergency repairs. Her office has seen a culture of lax bill collection in various governments across the state, which only makes the problem worse. Sometimes if a local government cannot pay its bills, they go to a general fund for support. This is a short term fix that can cause more issues down the road, Edmundson said.

What does this look like in an actual North Carolina town? Mayor Brown of Bethel says she had to start making difficult decisions for the citizens of her town. “You have to do what you have to do in your community in order to survive and thrive,” she said.

Currently, Bethel has a pumping station in an area that is at risk of flooding, and due to COVID-19, some in the community stopped paying their bills. Brown said loans are not the answer for Bethel. She and the town manager applied for grants but have been turned down. They changed strategies and are currently looking at merging with Greenville Utilities Commission.

What are some long-term solutions for these problems? Education, said Edmundson. Her office believes in helping small cities understand their financial situation. They recommend getting a rate study done and helping the local government come up with benchmarks to understand their financial health. It’s all about helping the rural place make informed choices about their way forward, she said.

All three panelists agreed that small rural places need to keep an open mind about regionalization. It allows you to expand your customer base, avoid bringing on more debt with loans, and in sharing resources, the system can be made more viable for everyone.

“We do need to reach out and grab everything that we can get in order to save our towns and to protect our citizens.” – Mayor Gloristine Brown of Bethel

Recommended reading