|

|

Last month, Secretary of Education, Dr. Miguel Cardona, gave a speech calling multilingualism a superpower, but the unfortunate reality is that in North Carolina and across the United States, multilingualism isn’t always cast in such a positive light.

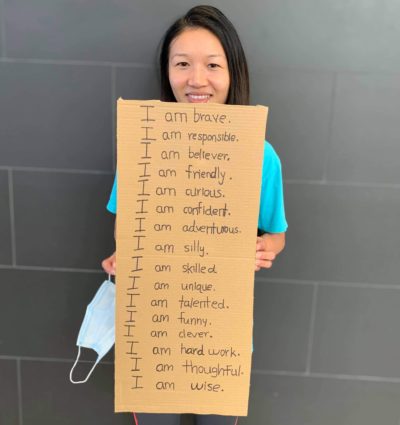

As educators, we want to promote asset-based perspectives and continue to reject deficit-based perspectives of our students. It is with this mindset and motivation that scholar, Tara Yosso developed the concept of community cultural wealth (CCW). Yosso’s basic assertion is that minoritized communities are culturally wealthy as seen through the six forms of capital she has identified, and that communities — including classroom communities — are enriched through these various capitals. Such forms of capital include aspirational, linguistic, familial, social, navigational, and resistant capital.

Forms of capital & their applications

Aspirational capital is the ability to maintain hopes and dreams for the future, even when there are a multitude of barriers. Aspirational capital is seen in the refugee teen who flees genocide, relocates to America, learns a new language, and clings to her dream of becoming a fashion designer. To hope against hope takes great courage and displays an aspirational wealth, which ultimately serves to enrich herself and those around her.

Linguistic capital embodies not only communication through multiple languages but is often accompanied by excellent storytelling skills. Linguistic capital is a bridge builder. Frequently, multilingual children become language brokers for their families, translating between their parents and other adults. Immigrant youth report feeling as though their linguistic abilities make them stronger people. Community cultural wealth is communal in nature, and linguistic capital increases the availability and ease of sharing such wealth within a linguistically diverse environment.

Linguistically diverse communities often function as families. Familial capital does not just pertain to actual blood relations, but rather it expands to extended family and kinship communal bonds. As families within a community look to one another, they often find that they become connected with others who have similar shared experiences. Familial capital allows for a community to serve as a family and thereby strengthen the whole group.

The multifaceted networking system of community resources is considered social capital, and it emphasizes the ability to function within the confines of schools, job markets, healthcare systems, and judicial systems. Historically, minoritized people have created and maintained their own social networks, while simultaneously being systematically locked out of other social networks.

Social capital is closely related to navigational capital, which deals with immigrants attempting to maneuver through a system which is both foreign and not designed for them. Navigational capital is both social and psychological and requires more than simply knowledge. Such maneuvering requires mental fortitude to press through the racism embedded within the system. Immigrants and people of color undergo what Arline Geronimus refers to as “weathering,” which is a phenomenon characterized by the long-term physical, mental, emotional, and psychological effects of racism, othering, and exclusion. This “weathering” is a steeling of the self in order to rise to the occasion of social navigation within a broken, biased system.

The final capital that Yosso explores is resistant capital, which is rooted in the idea that subjugated people must challenge inequity through opposition. Resistance can take on a myriad of forms, but is most often carried out communally. These knowledges and skills gained through this collective resistance can inform and inspire generations of future activists. Resisting so that one might force others to see their humanity is an essential part of being human.

An additional form of capital

Immigrants, multilingual learners, and other minoritized communities in the United States are still fighting to be humanized and still fighting for their cultures to be valued. The community cultural wealth framework set forth by Yosso has been built upon by others in their efforts to highlight the long-ignored wealth contained within historically marginalized communities.

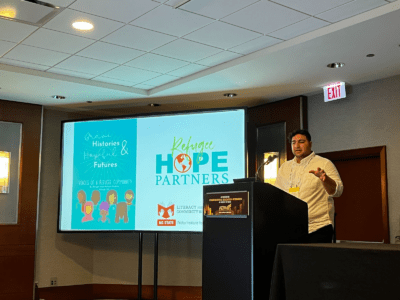

Another scholar, Dr. Rosa Jimenez, adds an additional form of capital to the concept of community cultural wealth. She names migration capital and defines it as the knowledge and skills gained through the experience of migration/immigration to the United States or its borderland. The actual experience of migrating is usually life-changing — and sometimes harrowing. For most refugees, reaching the United States is a multi-year process. The funds of knowledge immigrants possess from their immigration experience serve as sources of knowledge for everyone around them who wishes to utilize the knowledge gained through their experience; in this way community cultural wealth is a shared resource.

Classrooms of collective strength

The multifaceted nature of community cultural wealth needs to be taken in its entirety, encompassing all known forms of capital and making room for yet named forms. The tremendous wealth of marginalized communities is evident and undeniable as it is observed through the daily strength minoritized individuals and communities display. As educators, it is imperative that we recognize these assets and work towards incorporating students’ experiences into our content and curriculum, so that our classroom can function as a community of collective strength.