|

|

As an educator, it feels nearly impossible to get through a week without seeing or hearing mention of “learning loss” due to COVID-19. I understand the concern for students not being provided the opportunity to grow as they would have had this pandemic not derailed them (and everyone else). But every time I hear about learning loss, something inside me cringes. I have been reflecting on why this makes me bristle.

I am acutely aware of both educational disruptions and reading issues. As an educator to adolescent refugees with limited or interrupted formal education, I have seen the toll that educational interruptions can take. I have a master’s degree in reading education and am working on my doctorate in literacy and English language arts. I value literacy and work to improve, expand, and protect people’s access to literacy. So why would I take issue with the idea of learning loss?

My answer rests on my understanding of what it means to be able to read. I believe that in order to read the word, one must also simultaneously “read the world,” because authentic understanding of a text is intertwined with a rich understanding of the world. This is a foundational tenet in critical literacy, which is an approach to reading, and also a way of being, living, and learning. Because of my commitment to and belief in a critical approach to literacy instruction, I place a high value on the knowledge that students gain through life and experience.

I often turn to my students to gain insight into their lives and perspectives. I asked some of them, “What have you learned this past year?” One student answered me with this insight, “I learned that family matters and is more important than anything else. I also learned that isolation hurts more than we can imagine. And life is shorter than we think. Nothing is permanent, and we should enjoy and take advantage of every moment while we can.”

There is tremendous value in learning these life lessons about family, mental health, and the brevity of life. The value wrapped up in these lessons may not be quantified on exams or through growth scores, but that does not relegate this learning to a lesser sort of knowledge.

Our experiences increase our understanding. I was recently listening to Helen Reddy’s 1971 song, “I am Woman.” In the chorus she sings, “I am wise/But it’s wisdom born of pain/Yes, I’ve paid the price/But look how much I gained.” This song made me think of my students. Our students are wiser from their experiences. As a result of the past year, they will read the world and word differently, with more insight than before.

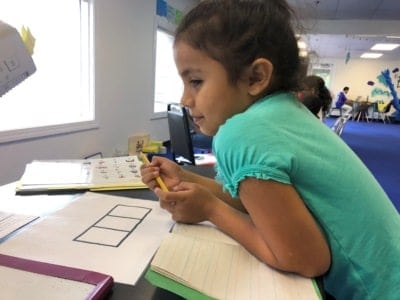

As educators, we have the opportunity to center student voices and consider their experiences as a form of capital. If we can embrace that these “learning losses” are, in fact, only “schooling losses,” then we can better learn from and with our students, as together we explore all that life has taught us in this difficult year. We can help our students to read both the word and the world. In doing so, we can apply these critical literacy concepts:

—Seeing the patterns, complexities, and interrelatedness of the world.

—Naming structures and ideas.

—Envisioning possibilities.

—Seeking to reshape inequities.

If we approach literacy in such a way, then we will see that our students have gained new insight as they have gained more understanding of the world. This greater insight into the world will be visible in their understanding of the word.

Recommended reading