Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published by Brown Center Chalkboard, a blog by The Brooking Institution.

School libraries have become a key battleground in contemporary culture wars over public education. In the 2021-22 school year, PEN America reported a record-setting 2,532 book challenges affecting 1,648 different titles in 138 school districts. Many of the challenged titles contain content related to LGBTQ+ issues or race/racism, topics that have also been the concern of state legislative efforts.

For a new study, I assembled data on hundreds of titles in public school libraries across the country. I collected this data by first curating book lists in several areas, including best-sellers, award-winners, and books that deal with controversial content including LGBTQ titles and books on race/racism or abortion, and then searching publicly accessible school library catalogs in the spring of 2022 for books on those lists. The list of titles across controversial topics includes both fictionalized stories and nonfiction titles. I also estimated the total number of books in the library and the library acquisitions rate (the share of books recently added to the library’s collection).

My school library sample consists of 5,240 elementary/middle and 1,391 high schools in 48 states. This sample includes schools in rural and urban areas, schools in counties with conservative and liberal political leanings, and schools that serve students of very different backgrounds. I use these data to identify patterns in library resources and content, especially as they relate to political preferences, state laws, and book bans.

Here, I describe some of the main findings from that work.

Finding #1: Libraries in low-income areas have lower staffing levels and less up-to-date collections.

First, I consider how library resources and collections quality vary for different types of schools. Schools with larger shares of white students, schools located in high-income areas, and schools in non-rural areas have better-resourced libraries and/or more up-to-date collections than their counterparts. The gaps are especially large between schools in low- and high-income communities (community income measured using the school neighborhood income-to-poverty ratio per the 2018-19 NCES EDGE school neighborhood poverty estimates). Compared to school libraries in low-income areas, school libraries in high-income areas have higher book acquisition rates (2.05 vs. 1.40) and employ more full-time equivalent librarians (1.12 vs. 0.80 per school). School libraries in high-income neighborhoods also have nearly twice as many recent best-sellers in their catalogues for young adults (18.58 vs. 9.44 titles) and middle grades (8.43 vs. 4.02 titles).

Finding #2: Access to controversial content is related to local political environments.

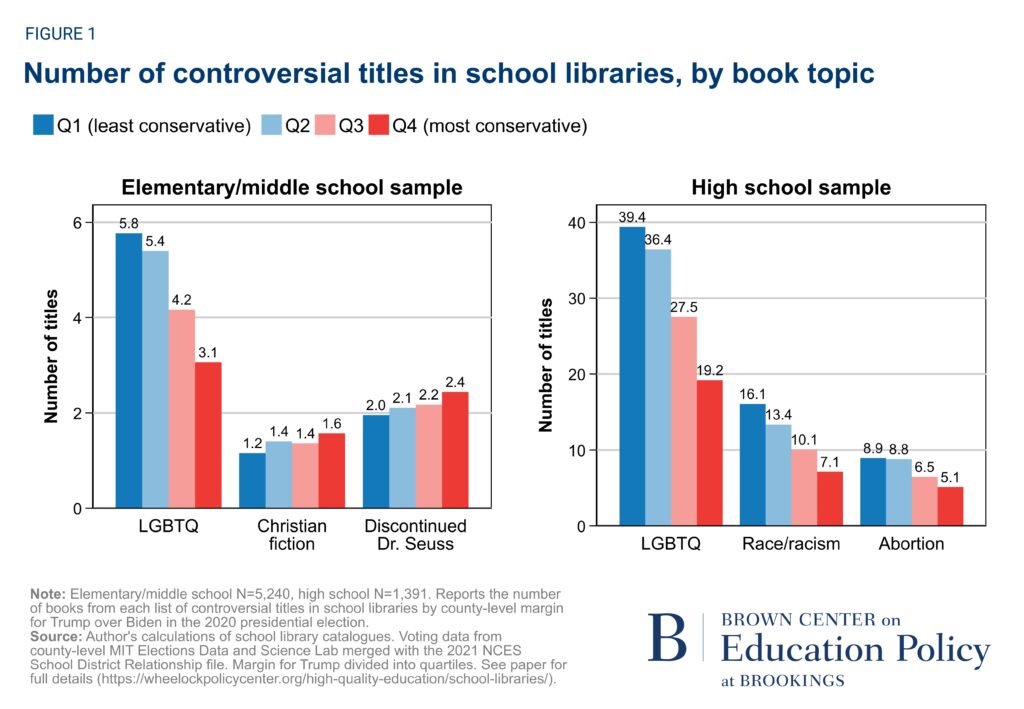

Next, I examine whether the prevalence of books with controversial content is related to local political environments and state laws. Figure 1 shows the number of books from each list of controversial titles in school libraries in more and less conservative communities, which I define based on the margin that voted for Donald Trump over Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. School libraries in the most conservative areas have fewer LGBTQ+ titles and fewer books that deal with race/racism or abortion than libraries in the most liberal areas. Libraries in conservative areas also have more Christian fiction titles and more Dr. Seuss titles that were discontinued from publication in 2021 because of racist imagery.

Similar patterns appear even after controlling for the number of books in the library, the acquisitions rate, and student enrollment at the school. These estimates indicate that a one standard deviation increase in community conservatism decreases the probability of finding a title from my list of books on race/racism by 3.2 percentage points (a 20% reduction relative to the sample mean of 16%) and decreases the probability of finding an LGBTQ+ title by 4.0 percentage points (12.9%) in high schools. In elementary/middle schools, a one standard deviation increase in local conservatism decreases the probability of finding an LGBTQ+ title by 1.9 percentage points (21%).

Controversial content is also associated with state laws that restrict curricular content. Libraries in states with anti-CRT laws are 3.5 percentage points (46%) less likely to have The 1619 Project, a particularly contentious publication that reframes American history around slavery and its legacy. Elementary/middle school libraries in states that have recently passed laws to restrict how schools talk about gender/sexuality are 3.6 percentage points (40%) less likely to have an LGBTQ+ title. These relationships control for local political preferences.

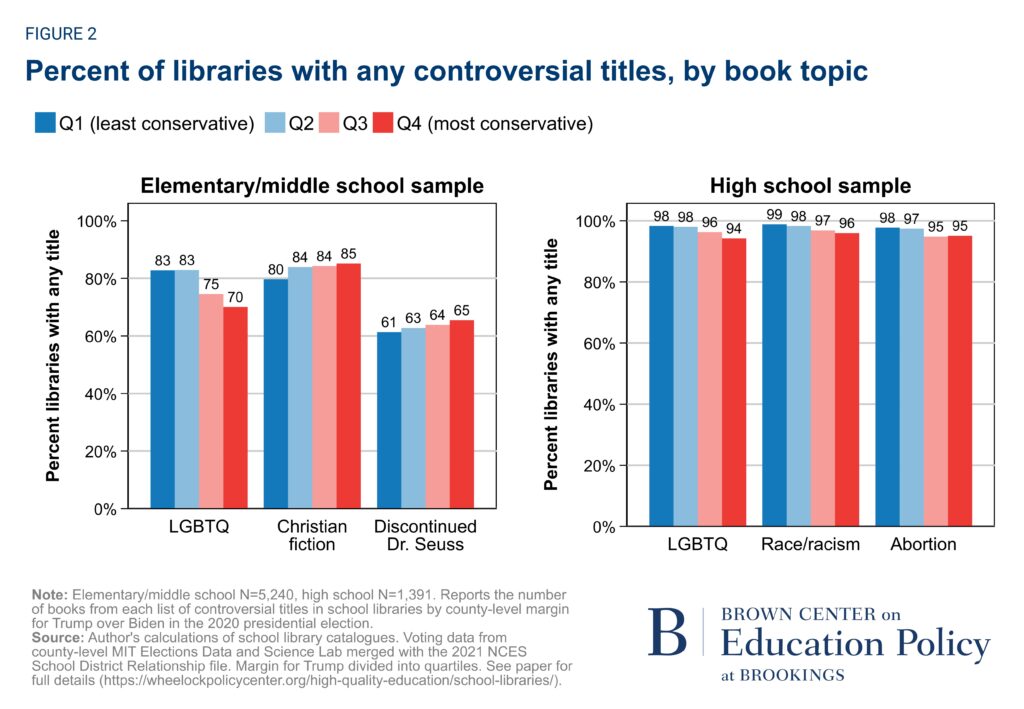

I note that despite these relationships, most schools in my sample have at least some controversial titles. Figure 2 presents the share of libraries that have at least one book from each list of controversial titles by quartile conservativism. At least 96% of libraries had at least one title from each of the LGBTQ+, race/racism, and abortion book lists. Even in the most conservative areas, the share of libraries with at least one book from each list of controversial titles was high (94%+). More than three quarters (78%) of elementary/middle schools in my sample had at least one title from the LGBTQ+ book list, including 70% of schools in the most conservative counties.

Finding #3: Book challenges may have chilling effects on the acquisition of LGBTQ+ content.

Finally, I consider whether the meteoric rise in book challenges in the 2021-22 school year has affected the type of content librarians are selecting for their collections. To do this, in October 2022 I searched high schools in my sample for 65 recently published LGBTQ+ young adult titles. I merged this to district-level data on book challenges from two datasets maintained by PEN America and the researcher Tasslyn Magnusson. My sample includes 82 schools in 43 school districts that were subject to book challenges in the past school year. I then estimated the relationship between being in a school district that was subject to a book challenge in 2021-22 and the probability of having one of these recently published LGBTQ+ titles. Importantly, I control in these estimates for the number of LGBTQ+ titles from the list of 100 older titles I searched for in the spring of 2022. Controlling for the number of titles found in the spring allows me to adjust for the library’s baseline preferences for LGBTQ+ content.

I find that schools in districts that were subject to book challenges over the last school year were less likely to have added recently published LGBTQ+ titles this fall. Specifically, libraries in districts subject to challenges were 0.55 percentage points less likely to have a recent LGBTQ+ title, a 55% decrease relative to the sample mean. I interpret this as suggestive evidence that book challenges are having “chilling effects” on the acquisition of LGBTQ+ content, leading librarians to avoid purchasing content that parents or politicians could find objectionable.

Conclusions

The recent flurry of political activity aimed at public school libraries has drawn attention to this relatively understudied school resource. My study points to reasons for concern, optimism, and continued attention on the state of school libraries.

The gaps I find in library resources between schools in low- and high-income communities is one area of concern. While research on the causal relationship between library resources and student outcomes is limited, a number of studies suggest a link between school library programs and student achievement. Moreover, these gaps imply differences in access to reading materials that may affect students in ways not reflected in test scores, including by exposing children to stories that expand their horizons or affirm their lived experiences.

I also find that access to books with controversial or ideological content differs for communities across the political spectrum. In the United States, local school districts exercise substantial autonomy over what students are taught and how. Given this, it is not surprising that school librarians tailor their selections to match the preferences, priorities, and (perhaps) biases of their local communities. More surprising is the finding that books with controversial content are still widely available on library shelves, at least to some extent. If one goal of school library programs is to facilitate access to diverse and challenging material, this finding suggests that many libraries are meeting that goal.

Most relevant to policymakers are my findings on state laws that restrict curricular content and book challenges. Anti-CRT and anti-LGBTQ laws are negatively associated with the availability of certain kinds of race/racism and LGBTQ+ books even after controlling for local political preferences. While these findings express correlational (not causal) relationships, they are consistent with the interpretation that state laws shape school library selections above and beyond what local communities would prefer. More compelling is the evidence I present on the “chilling effects” of book challenges on the acquisition of new LGBTQ+ titles. While more research is needed to confirm these findings over time, these chilling effects may have much larger effects on the type of content available to students in public school libraries than the removal or imposition of additional restrictions on individual titles implicated in book challenges.

School libraries have become contested spaces in public school buildings. Only time will tell whether the political battles that have erupted over the content that students encounter at school will have lasting impact on students or the types of ideas and stories they find on library shelves.