Like many millennials, I’ve tried my hand at some baking in these quarantine times. And while I am naturally more of a renegade than a recipe-reader in the kitchen, I have learned the hard way that there are some ingredients that you simply can’t leave out if your baked goods are to land within shouting distance of edible. No matter how much creative variance in the amount of sugar or salt or chocolate chips I spin into batches of my homemade s’mores bars, for instance, without the necessary amount of flour, the project will end in a smoking, liquified mess (true story).

If you were to write up a recipe for statewide public education excellence, North Carolina would have almost all of the necessary ingredients. We’ve got the deep history, the committed personnel, the active local organizations, the diverse economic and collegiate support, and the robust legal foundation, all in ample supply. But without the necessary catalyst of sufficient political will from our state legislature, these ingredients will remain unable to rise to their full potential and create the powerful result of education equity and excellence in North Carolina.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

First, we’ve got the history. North Carolina has the deep historical foundation of a state brimming with potential to serve as a national public education exemplar. Within a broad civil rights context, North Carolina has been home to both transformative leaders, like Pauli Murray and Julius Chambers, and catalyzing events, like the Greensboro Four sit-ins and the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee at Shaw University. More specifically, North Carolina’s history as a national exemplar in public education during the 1990s under the leadership of Gov. Jim Hunt gives a useful blueprint for future success.

Second, we’ve got the personnel. This school year perhaps more than any other, North Carolina public school teachers, staff members, and administrators have demonstrated their unwavering commitment to creatively adapting to challenges both new and old to do right by their students, families, and colleagues. In particular, incredible teachers, administrators, and leaders of color across our state push North Carolina public education toward greater racial equity.

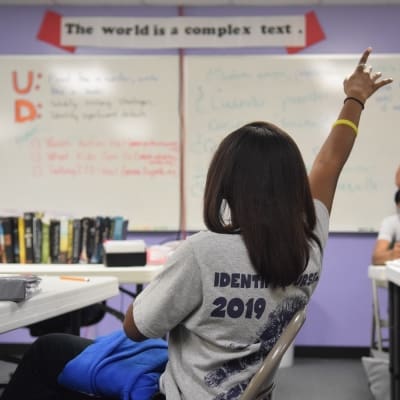

Third, we’ve got the local and statewide organizations. You’d be hard pressed to find a town, city, or region of North Carolina that doesn’t have groups of parents, neighbors, and community leaders working tirelessly to advocate for the needs students with disabilities, English Language Learners, students of color, low-income students, undocumented students, LGBTQ students, or just students in general. In organizations big and small, formal and ad hoc, and from Murphy to Manteo, folks are fighting the good, difficult, and often thankless fight of education equity.

Fourth, we’ve got the economic and collegiate support. Where North Carolina’s traditional economic sectors like agriculture and textiles provide ample opportunities for student technical training and experiential education, more modern industries like Research Triangle Park’s tech companies and Charlotte’s financial sector provide nationally-recognized STEM services, corporate leadership, and technological resources. North Carolina’s broad slate of colleges and universities — including many excellent HBCUs — provide access to incredible academic and research resources and opportunities, and often house vital teacher training programs. And both businesses and colleges are constantly looking for well-educated, well-rounded students to join their ranks.

Finally, we’ve got the legal foundation. While the federal constitution is notably quiet on education rights, the North Carolina Constitution speaks loud and clear: As interpreted by the North Carolina Supreme Court in the landmark case Leandro v. State, it enshrines in all North Carolina students the constitutional right to a sound basic education provided by the state.

Related Readings

Notably, this guarantee is not merely one of education access, but education adequacy. Put differently, the state constitution does not simply promise that the state will operate a public school in a student’s community that lets her in the front doors. Rather, it promises that that within that school, she will receive an education of quality at least adequate enough to fully prepare her to participate in society.

Collectively, North Carolina has nearly all of the vital ingredients necessary to be a national exemplar in public education equity and excellence. Why, then, has it toiled in the bottom half of states in key measures of K-12 education achievement, with student performance largely stagnate, for at least the past decade? Because, like my ill-fated s’mores bars, North Carolina currently lacks a key ingredient that helps the rest rise: political will from the state legislature to adequately support public education.

For at least the last decade, the General Assembly has systematically underfunded North Carolina’s traditional public school system while disproportionately supporting school choice and school privatization measures. As repeatedly confirmed in court through the ongoing Leandro litigation, the General Assembly has continually failed to fund public education at levels adequate to ensure the provision of a constitutionally adequate (let alone excellent) education to all North Carolina students.

Compared to other states, North Carolina recently ranked 48th in raw funding level and 49th in relative funding effort (funding as percentage of GDP) in the Education Law Center’s annual assessment of school funding. Without adequate funding, the other key ingredients of North Carolina education excellence will continue to do their absolute best to forge progress, but will not be able to realize their true potential.

Systemically speaking, the problem is not the oft-mythologized “ineffective teacher,” “hapless administrator,” “unengaged parent,” “troubled student,” or “broken community.” The problem is a lack of political will to robustly and unapologetically support public schools and marginalized students. Period.

This is not to say that funding public education at constitutionally-adequate levels will magically eradicate education inequity overnight. It will, however, serve as a vital first step toward supporting the existing personnel, programs, and resources already working hard to bend North Carolina public education toward equity and excellence. And because public education is an inherently public good, relying on private, market-based principles for school funding will only perpetuate existing inequities in which the most racially, economically, and politically privileged wield disproportionate power.

In this legislative session, the General Assembly is again presented with the opportunity — indeed, the constitutional responsibility — to provide this key missing ingredient. Hope springs eternal, and I welcome the possibility of newfound political will toward adequately funding North Carolina’s public schools such that all students will have the opportunity to receive a sound basic education.

But if previous legislative recalcitrance continues, I will find that hope elsewhere: in our deep history of progress, in the profound resilience of marginalized students and families, in the unbending commitment of their teachers, administrators, and advocates, and in the legal power of the judicial branch to protect the constitutional rights of students. Together, we can get this recipe right and make North Carolina a national exemplar of educational equity and excellence.

Recommended reading