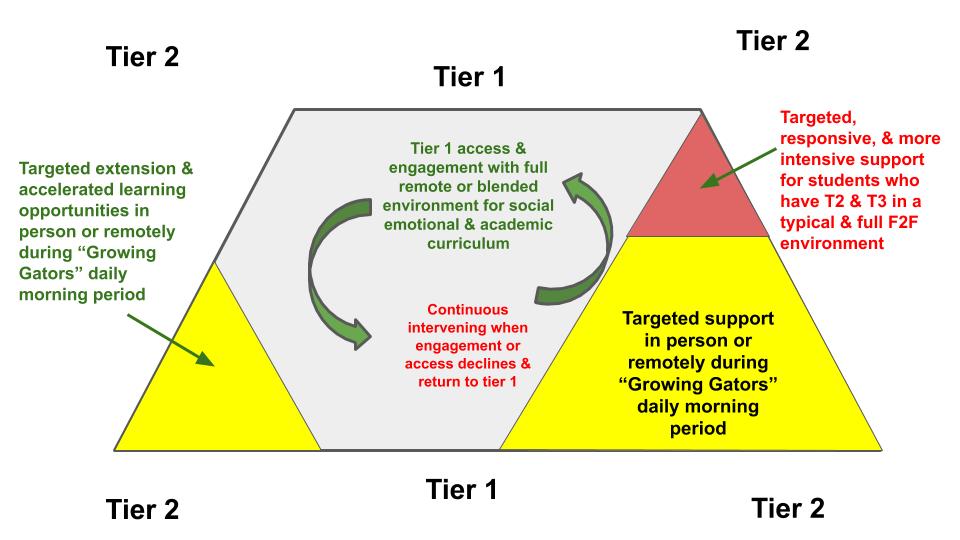

A note from the author: In a multi-tiered systems of support approach, tier 1 refers to the social-emotional and academic instruction in which the whole class or whole school participates. It is typically effective for about 80% of the school population. Tier 2 is when some students — typically between 15-20% of the population — receive more targeted support on top of tier 1 (e.g. this is accounted for in the master schedule).

Tier 3 refers to even more intensive and individualized support for a few that is again layered in addition to tier 1 and 2. At the tier 2 and tier 3 levels, in an ideal scenario, school staff are regularly monitoring how the student responds to intervention. You can learn more about MTSS through the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s Integrated Academic and Behavior Systems webpage.

In her third grade year, Ka’Dayjah experienced traumatic events that resulted in missing many days of school. Since then, each year, her teachers and school staff have made sure she had tiered social-emotional and academic supports in place at school to assist her growth and understanding.

Now, as a sixth-grader at a brand new school, she started the 2020-21 school year in a full remote learning environment. Some students returned face-to-face recently in a version of plan B, or a hybrid model. Students like Ka’Dayjah across North Carolina are adjusting to fluid school scenarios for the 2020-21 school year while school staff across the state are considering how best to support their evolving needs amid challenges unlike ever before.

As more and more attention is being given to multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) as a framework for school improvement in North Carolina schools, we need to remain vigilant of our language and our approaches. MTSS is not a process for an individual child, it is not a label for students, and it is not only about reading and math. At its core, it is about school improvement, yet we often see improvement and success through very narrow lenses.

A recent article in the National Association of School Psychologists’ newsletter made an excellent point that oftentimes, multi-tiered systems of support are solely viewed through the lenses of tiers 2 and 3. If this error is made in the understanding of MTSS post-pandemic, it could have detrimental impacts on the possibilities of school transformation and individual student growth.

Here are six considerations from my perspective as a middle school coordinator for multi-tiered systems of support.

Attendance and engagement (in)accuracy

In remote learning or any kind of hybrid environment, attendance and being marked “present” for the day are quite complex and not synonymous with “presence” or “engagement.” Schools have had to recreate systems for attendance and other key data systems overnight.

The main point here is to ensure your school’s attendance (or engagement) data is as accurate as possible throughout your current (and evolving) model(s), because we cannot intervene socially, emotionally, and academically if a student is not present and engaged in the tier 1 foundation.

Before talk of interventions: Is your new tier 1 accessible, solid, and equitable?

Even if our attendance is accurate, another key concept behind an MTSS approach is to always analyze the strength and relevancy of our tier 1 instruction. How can we possibly justify tier 2 and 3 interventions with individual children if we are not first ensuring access to tier 1 for all students?

Our school’s key problem solving question since the start of a remote school year has been: Who are our students that are not accessing the tier 1 curriculum consistently and how can we problem-solve those barriers first? Do they need a laptop? A hot spot? Child care? How can our community partners support us and them?

Once we have this question answered we can move to: How solidly grounded in local context and research is our tier 1 social-emotional and academic instruction within the schedule and learning format our school is in? What are the research-based strategies that make for strong tier 1 instruction in whatever your instruction model is? Are they culturally responsive or are they grounded in dominant cultural perspectives? How will we gauge that they are in place for the entire school?

In an MTSS, we always analyze our tier 1 for quality. To say that doing so is important for a school during a pandemic is a huge understatement. It is imperative and arguably a moral obligation.

Fill gaps in your students’ COVID-19 tier 1

By this time in the year, most schools are experiencing a heavy load of missing assignments. Before considering intervening in traditional ways, schools need to find ways to ensure students access the tier 1 curriculum they have missed since March or more recently.

While we do this for the more disadvantaged students whose COVID-19 experience has probably been unlike many middle-class educators’, we can look for ways to incorporate enriching experiences for those who have been able to engage with the new tier 1 curriculum. There are so many possibilities for innovation in teaching and learning here, but suffice it to say that innovation and the testing culture and machine that MTSS is aligned with aren’t exactly on the same branch of the educational family tree.

Explore curiosity, interests, passion, and purpose. Enjoy learning with your students.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Make tier 2 and tier 3 responsive and feasible

Next, and still before implementing more traditional reading and math tier 2 and 3 interventions, schools should be asking: What is the most responsive approach or intervention that individual students and families need?

More than ever, we need to problem solve the individual needs of students with their families, not for them. Let’s not just dump an extra period for math fluency intervention into a child’s schedule without consulting with the child and the family.

What is feasible and needed for that family and student amid ongoing COVID-19? How can we connect our schools with additional community partners to fill these gaps now and into the future? Attempting to repackage pre-crisis schooling into whatever current version of plan A, B, or C we are operating under is not healthy or sustainable for our communities.

Embrace the pause: Plan long-term

Speaking of sustainability, what schools could do during this strange and evolving time is to review their protocols for problem-solving and expand the tiered curriculum to integrate more of students’ lived experiences and less of standardized test objectives.

Do your protocols place the voice of the student front and center, or at all? Have they shifted to take into account the pandemic and intense racial and social injustices that our students have been observing in the last several months while they have been out of our sight? Have you interviewed or surveyed your students lately and given them an opportunity to inform tiers 1, 2, and 3 and how they contribute to or take away from positive school climate?

Do your materials at all tiers include diverse representations of your students’ lived experiences, cultures, and communities? What is the percentage of student demographic subgroups on your campus compared to the percentage of identified learning groups on your campus (AIG, EC, MTSS, etc.), and what does this say about your campus’ cultural responsiveness and competence?

What, really, is school improvement and success?

From March to June, most of the education world took a huge pause. Unfortunately, some teachers will tell you that some schools have returned to a dangerously fast race based on the way we always did things, while we are still under-funded and under-resourced. While underfunding and under-resourcing are a separate topic, this unhealthy and unsustainable pace is strongly linked to our outdated accountability model.

The current accountability model, with its imbalanced emphasis on standardized testing that is highly focused on reading and math, so strongly infiltrates the educational psyches in every place where decisions for children are being made that its influence has become dangerously invisible at best, and dangerously harmful at worst.

It is no surprise that the pandemic will have impacted the growth of children across the state and globe. However, math and reading scores are not the only ways to show a student’s, teacher’s, principal’s, or school’s success. Don’t get me wrong: I value reading and math. However, the lived experiences of my students should be privileged before — or at least alongside – top-down legislative expectations related to math and reading.

Building tiered curriculum, instruction, and environment around my students’ lives and what is actually relevant to them feels more sustainable, fun, and meaningful. It also feels like a far greater sign of success for a community in the long run. This way of thinking about teaching and learning will not mesh with the accountability model or its impact on our collective psyches, but the pauses the pandemic grants us are a perfect time for schools, districts, and communities to identify their own versions of and measurements for success.

So, before rushing to implement evidence-based math and reading interventions — that are probably founded in and researched by dominant cultural groups’ perspectives anyway — ask yourself and your community a transformational question: How might we ensure our students’ experiences across tiers are more grounded in the context of their lived experiences and the future they inherit so that school success is more reflective of our community values?

Recommended reading